|

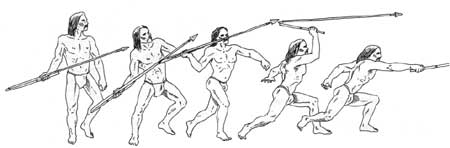

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 2:

The Prehistoric Peoples of Jackson Hole

By Stephanie Crockett

|

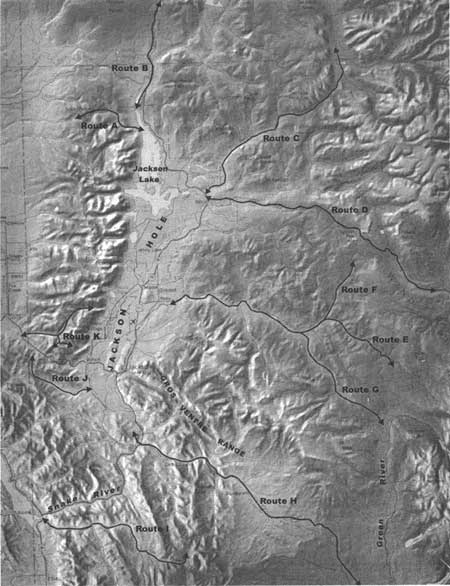

| Figure 1. Standing on the east shore of Jackson Lake, rancher and amateur archeologist W. C. "Slim" Lawrence stands near a prehistoric fire hearth, November 1936. At the time Lawrence gathered artifacts, the property on which he collected was privately owned. It is illegal to collect archeological artifacts within Grand Teton National Park. National Park Service |

During the 1930s, a Jackson Hole ranch foreman named W. C. "Slim" Lawrence began to collect artifacts along the north shore of Jackson Lake. Over the next 30 years, Lawrence's collection grew to number in the thousands and would help illuminate approximately 11,000 years of human habitation in a place we now call Jackson Hole. [1] The artifacts recovered by Slim Lawrence, combined with subsequent professional archeological research, allow us a glimpse of what life would have been like for the prehistoric inhabitants of Grand Teton National Park and Jackson Hole [see Figure 1].

Professional archeological investigations began with intensity in Jackson Hole during the 1970s. At this time, large-scale investigations were conducted by archeologist Gary Wright and his colleagues from the State University of New York at Albany. Wright and his associates formed an archeological "model" of prehistoric life in Jackson Hole—a hypothesis about the lives of the area's early peoples. [2] This chapter will briefly describe this model and its importance in later research. Using Wright's model as a framework, clues to the general subsistence and travel patterns of Jackson Hole's early populations are explored. Finally. because American Indian peoples do not exist solely within the realm of history, and tribes—such as the Wind River Shoshone—are still culturally tied to Jackson Hole, a final section of this chapter includes a discussion of these modern cultural ties.

An Archeological Model of Prehistoric Life in Jackson Hole

Throughout prehistory, the people of the mountain and foothills environments of northwest Wyoming subsisted as hunter-gatherers. As such, the early people of Jackson Hole most likely resided in the valley on a seasonal basis. Highly mobile, these individuals took advantage of ripening plants and migrating game animals. Prehistoric people also needed an intimate knowledge of the landscape and the behavioral patterns of game animals. However, anthropologists postulate that wild game, although essential to the prehistoric diet, was less predictable and, therefore, of secondary importance. By contrast, the abundance of edible and medicinal plants was critical to the survival of these people. Observation of such plant species on and around archeological sites has led to the development of a predictive archeological model of prehistoric life in and around Jackson Hole.

Basically, archeological models take a general theory and apply it to a limited set of conditions. By observing this limited set, the archeologist can then test his/her hypotheses. Using a model, archeologists can predict where certain types of archeological sites can be found. For example, archeologist Gary Wright and his colleagues formulated a model of "High Country Adaptations." [3] Wright and his colleagues observed the available edible and medicinal plant species within the Jackson Hole region, and then determined where prehistoric peoples may have traveled and settled based on the availability of these plant resources.

Wright's model is based on the theory that the areas earliest humans utilized the valley floor of Jackson Hole in the early spring, then moved to higher elevations during the summer and early fall to follow ripening plants. The first spring plant foods on the valley floor ripened between the third week in April and the middle of May. Early season root crops included spring beauty, bitterroot, Indian potato, biscuit root, and fawnlily, as they are commonly called. All of these plants have fleshy taproots, corms, or bulbs, are available throughout the spring and summer months, and continue to bloom just behind the receding snows at subsequently higher elevations. Archeologists know that American Indians historically harvested these plants for their roots before or while in bloom, when the nutrient content is high and the plant is readily observable on the ground surface. Thus, according to Wright's model, prehistoric people moved into Jackson Hole by late May or early June, and subsisted predominantly on root crops through the month of June. [4]

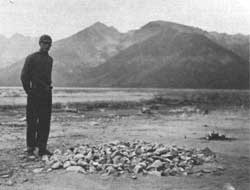

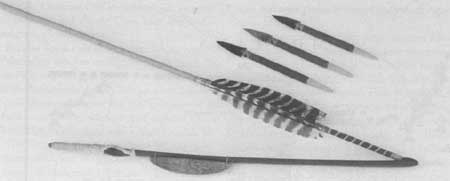

According to Wright, the people living in the northern part of Jackson Hole probably spent their early summers at the mouth of the canyons in the northern Tetons. These people established large "base camps" at the head of Jackson Lake, at elevations of less than 7,000 feet above sea level (asl). Archeological evidence supports this theory, as a wide variety of tools, hearths, and roasting pits have been recovered from probable base camp sites, such as the Lawrence Site, on Jackson Lake. The Jackson Lake base camps were apparently used for a variety of activities, such as tool making, food processing, and even fishing, as evidenced by the notched stone artifacts probably used as fishing net weights [Figure 2]. [5]

|

| Figure 2. Fishing net weights. Typically, these weights are approximately 4 to 5 inches across. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Wright's model also suggests that, as the snow melted, "specialized parties" traveled into Webb, Owl, and Berry Creek Canyons to collect ripening plants. Although Wright had yet to conduct systematic research of high-altitude areas in the park, he theorized that the sites left by these gathering parties would be relatively small and contain specialized "tool kits." Presumably, these sites were occupied for a shorter time by fewer people, all of whom performed the specialized tasks of plant gathering, plant processing, and some game hunting.

During the late summer, the large base camps moved up into the higher valleys of the northern Tetons. These base camps would be at an elevation of approximately 8,000 feet. From here, specialized parties gathered plants as they ripened in the highest mountain meadows. By late summer, the high mountains would have been thoroughly exploited, at which time the entire group moved westward into Idaho for the winter. [6]

A similar but separate model has been formulated for the southern half of Jackson Hole. Here, prehistoric people collected root and herb crops more acclimated to the drier benches and hillsides of southern Jackson Hole. These plants included sego lily and arrowleaf balsam root. Prehistoric people in southern Jackson Hole probably also harvested plants along the eastern side of the valley. Having wintered in the Wind River, Green River, or Bighorn Basins in northwest Wyoming, these groups entered the valley from the east, through the Gros Ventre drainage. This is evidenced by the high amounts of Green River cherts that have been found on archeological sites along the southeast end of the valley. [7] As the plants ripened and the season progressed, prehistoric people followed the maturing plants into the Gros Ventre Range to the south. By winter, they had moved into the warmer and dryer inter-montane basins east of Jackson Hole.

During the summer, the prehistoric people in and around Jackson Hole were primarily occupied with gathering plants, but they also hunted. Their travel patterns were in proximity to migrating animals such as mule deer, elk, and big horn sheep. [8] Indeed, bison supplemented the diet of Jackson Hole's prehistoric people. This evidence comes from bison bones recovered from sites within Grand Teton National Park and at the southeast end of the valley. [9]

With this archeological model as a framework for understanding the travel and general subsistence patterns of prehistoric peoples, it is now time to move on to the archeological data, most of which has been recovered since the formation of Wright's model.

The Archeological Record of Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park

The earliest human inhabitants of North America probably arrived from Asia, via the Bering Strait Land Bridge. This bridge connected the continents during the last Ice Age, for a period extending from 75,000 to 10,000 years B.P (Before Present). Archeological evidence from Eastern Siberia suggests that the first humans migrated into the New World no more than 22,000 years ago. Archeologists continue to seek evidence for an earlier arrival, but the current record suggests that by 12,000 years ago humans were living as far east as Maine and as far south as Costa Rica. [10]

The earliest evidence of humans in Jackson Hole dates to approximately 11,000 years ago. By this time, the massive ice sheet that had blanketed much of Jackson Hole had retreated from the valley floor. Through analysis of fossil pollen found at the bottom of area lakes, we know that plant communities consisting of shrubs and herbs had colonized the silt and outwash soils left behind by the receding glaciers by 11,200 years ago. Willows and juniper may have been present during this time period but, in general, the lower elevations of Jackson Hole were probably much like the high alpine meadows of today, with sparse vegetation and a short growing season. It was in this environment that the first humans ventured into Jackson Hole. [11]

So, who were these first intrepid humans to follow the receding glaciers into this high country?

The Paleoindian Period (12,000 to 8,000 B.P.)

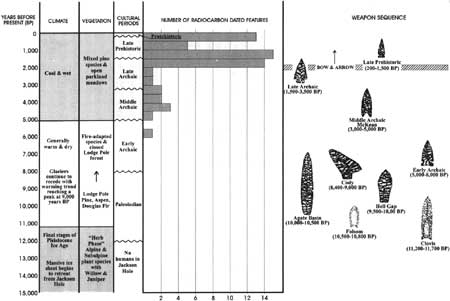

The earliest Jackson Hole artifacts made by human hands date to the Paleoindian period. This time period ranges between 12,000 and 8,000 years ago. During this time, the archeological record suggests that humans hunted with finely flaked, lanceolate-shaped, stone spear points. These points were hafted to a large spear that was either hand-thrown or projected by the use of an atlatl.

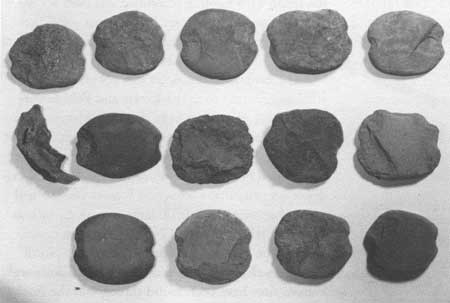

The atlatl is a simple but ingenious device that greatly enhanced hunting technology during this early period [Figures 3 and 4]. The atlatl is a carved wooden throwing stick, which was used in conjunction with a finely-flaked spear point, hafted to a short wooden dart shaft. The dart was attached to a larger spear that, in turn, was propelled by the atlatl. The atlatl throwing stick was fitted with a thong or socket to steady the butt of the spear, and was generally weighted by a smoothed bannerstone to add force to the throw. The atlatl thus became an extension of the hunter's arm to increase the velocity of the spear. This hunting technique was used across North America for at least 10,500 years, until the development of the bow and arrow about 2,000 years ago. [12]

|

| Figure 3. The atlatl was used for throwing short spears or darts. Tracks Through Time: Prehistory and History of the Pinon Canyon Maneuver Site, Southeastern Colorado. (National Park Service and U.S. Army) |

|

| Figure 4. Atlatl throwing stick, detail. Fingerloops and weighted bannerstone on lower left. Stephanie Crockett |

The earliest North American people to use the atlatl are referred to as the Clovis and Folsom cultures. These names are from the New Mexico towns where evidence for these earliest Americans was first discovered. The terms also describe the stone spear points used by these early hunters. Archeological evidence suggests that Clovis and Folsom peoples had a diet that relied heavily on large mammals, such as the now extinct species of North American camel, horse, bison and, for the Clovis hunter, the North American elephant known as mammoth. Clovis and Folsom sites have been found throughout the Rocky Mountain West, and as close to Jackson Hole as the Big Horn Basin near Cody, Wyoming. Isolated Clovis and Folsom spear points have also been found in a number of locations in the Green River Basin. [13]

Based on the paucity of artifacts found in Jackson Hole that date from this time period, it is impossible to know how long these populations lived in the area. Part of a Folsom spear point was found at an elevation of 9,000 feet, [14] in the Upper Gros Ventre drainage, which flows into Jackson Hole from the east. A lanceolate spear point was discovered at a site near present-day Astoria Hot Springs at the south end of Jackson Hole, while a spear point resembling the Clovis style was recovered from the Lawrence Site on the shores of Jackson Lake. To date, however, no remains of Clovis or Folsom prey have been found in Jackson Hole. [15]

As we move forward in time to approximately 10,000 years ago, the evidence for human occupation begins to increase and the picture of life in Jackson Hole becomes a little clearer. By this time, Englemann spruce and subalpine fir were on the landscape, and the whitebark pine, with its edible seeds, was quickly spreading throughout the region. Archeologists continue to refer to this as the Paleoindian period, yet the spear point styles have changed. Names such as Agate Basin, Hell Gap, and Cody (see time line) are used to describe some of the stone tools used during this time period. Although the styles changed slightly, spear points were still large and probably projected by the atlatl throwing stick.

|

| Jackson Hole time line. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) National Park Service |

More durable than bone, wood, and fiber, stone artifacts are often the only evidence that archeologists have to trace cultural and technological changes through time. In addition to stylistic changes, variations in the raw materials used to make stone tools can be an important indicator of cultural change. Throughout the Jackson Hole and Yellowstone region, volcanic activity deposited a valuable stone material that was used frequently by prehistoric people. Millions of years ago, as rapidly cooling lava flowed through underground fissures, a natural semi-translucent glass was formed. Subsequent glacial activity helped expose outcrops of this volcanic glass, known as obsidian. Obsidian's fine flaking qualities and ability to keep a sharp edge made it a popular raw material for prehistoric toolmakers.

Obsidian affords an added bonus for archeologists in that each volcanic flow has unique chemical elements. Through a technique called x-ray fibrescence, scientists can identify the exact chemical elements of a particular obsidian artifact. Under this procedure, the obsidian artifact is exposed to high-intensity x-rays. Different elements in the obsidian absorb and release these x-rays at different rates, which can then be measured. When plotted on a graph, the chemical "fingerprint" of an obsidian artifact is revealed. Scientists then compare this finger print to obsidian from natural outcrops across the region. A match of chemical components indicates the source for the obsidian in that particular tool.

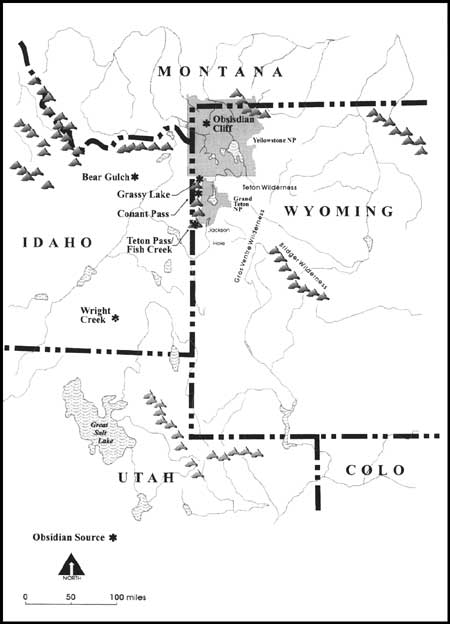

Several large outcrops of obsidian have been found throughout the region [Figure 5]. These sources include Obsidian Cliff in Yellowstone National Park, Bear Gulch in the Targhee National Forest, the Fish Creek sources in southern Jackson Hole near Wilson (commonly referred to as the Teton Pass sources), Wright Creek near Malad, Idaho, and the Grassy Lake and Conant Pass outcrops at the northern end of the Tetons. Paleoindian obsidian artifacts found in Grand Teton National Park chemically match some of these sources. X-ray fluorescence testing reveals that the most popular obsidian source for early Jackson Hole toolmakers was nearby Teton Pass. Obsidian Cliff in Yellowstone, Targhee National Forest and Wright Creek were also used, although to a lesser degree.

|

| Figure 5. Obsidian sources. (click on image for an enlargement for a new window) National Park Service |

Because Teton Pass is the source for the majority of Paleoindian obsidian artifacts in Grand Teton National Park, archeologists believe that humans entered the Jackson Hole valley via the south end, near the pass. However, the fact that the remainder of the artifacts came from a wide variety of regional sources indicates that Paleoindians were a highly mobile people. The distance between Obsidian Cliff, the most northern source, and Wright Creek, the most southern source, is more than 175 miles. [16] The Paleoindian peoples who frequented Jackson Hole apparently had an intimate knowledge of resources available throughout a rather large geographical area.

Bone is rarely preserved in archeological sites. As a result, excavations have revealed little if any evidence to indicate what species of game Paleoindians hunted while in Jackson Hole. Archeological sites just east and northeast of Jackson Hole suggest that around 10,000 years ago two separate cultural groups emerged in the region. One group adapted to the mountain and foothills environment, while the other adapted to the open plains. The groups living in the mountains, such as the Tetons, Wind River, or Gros Ventre Ranges, hunted mountain sheep and some mule deer. Meanwhile, the plains-adapted peoples developed sophisticated, communal bison-hunting techniques.

Traveling in groups, the plains hunters trapped great numbers of bison in arroyos (dry creek beds), sand dunes, or artificial corrals, where they killed them with hand-held spears or atlatls. In the mountains, hunting was done by smaller groups. Archeological evidence from the Absaroka mountains northeast of Jackson Hole, as well as studies of modern-day mountain sheep, indicate that mountain-dwelling hunters used nets to capture big horn sheep. The hunters strung a net, large enough to capture three sheep, across a known migration path. As the sheep became entangled in the net, the hunters killed them with clubs. A Paleoindian trapping net made of juniper bark cordage has been found in the Absaroka mountain range. Mule deer are a less predictable species, and were probably hunted individually with the spear and atlatl [17]

Plant materials have also been recovered from the Paleoindian period. Archeologists have found the remains of plant foods such as seeds, berries, roots, leaves, and bulbs dating to the Paleoindian period in cave sites northeast of Jackson Hole. Paleoindian food cache pits have also been found in the mountains of northwest Wyoming. These contained the remains of sunflower (Helianthus annus), prickly pear (Opuntia polyacantha), and amaranth (Amaranthus retroflexus). [18] Consequently, we can assume that Paleoindians in Jackson Hole ate these plants, and supplemented their diet with mountain sheep and mule deer.

The Archaic Period

Around 8,000 years ago, the warming climate of Jackson Hole reduced the glaciers to mere remnants high in the mountains. Also during this period, lodgepole pine became the dominant conifer in the area, growing in stands with aspen and Douglas fir. [19] During this time, prehistoric populations in the mountains of northwest Wyoming began to eat more small animals and wild plant foods. Changes in spear point styles and food-processing activities signal the beginning of a long period that archeologists refer to as the Archaic.

The Archaic period lasted approximately 6,500 years in this region, and has been divided into three separate periods simply referred to as Early, Middle, and Late Archaic. These divisions are based primarily on changes in spear point styles.

The Early Archaic (8,000 to 5,000 B.P.)

The Early Archaic period took place approximately 5,000 to 8,000 years ago. The oldest buried cultural deposits found in Grand Teton National Park were radiocarbon-dated to around 5,850 years ago, well within the Early Archaic period. [20] Radiocarbon dating is a technique that measures the amount of Carbon-14 that has decayed from a formerly living organism. All living organisms absorb an equal amount of carbon from the atmosphere. When an organism dies, it no longer absorbs carbon. The Carbon-14 in that organism then starts to convert to Carbon-12 at a known rate. By measuring the ratio of Carbon-14 to Carbon-12 in an artifact such as wood, bone, charcoal, or shell, the relative age of an object can be determined. [21]

|

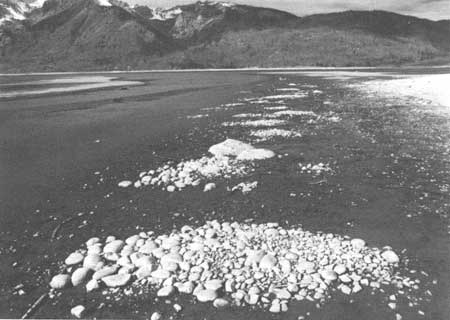

| Figure 6. Eroded and deflated roasting pits on shore of Jackson Lake. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

In Grand Teton National Park, the earliest radio carbon-dated deposits are from a large roasting pit found on the north shore of Jackson Lake (Lawrence Site). This pit was probably used for roasting local root plants, and is the earliest evidence for this type of activity in the park [Figure 6]. Early Archaic inhabitants of the Jackson Lake area, as would their successors, filled these pits with quartzite cobbles, which they had probably scoured from nearby hill sides. They would then build a fire on top of the cobbles. When sufficiently heated, the coals would be removed, and the rock-filled pits would serve as ovens. Similar roasting pits were described by the early Jesuit missionary-explorer Father Pierre Jean De Smet during his encounters with tribes in the Pacific Northwest:

They make an excavation in the earth from 12 to 14 inches deep, and of proportional diameter to contain the roots. They cover the bottom with closely-cemented pavement, which they make red-hot by means of fire. After having carefully withdrawn the coals they cover the stones with grass or wet hay: then place a layer of roots, another of wet hay, a third with bark overlain with mold, whereon is kept a glowing fire for 50, 60 and sometimes 70 hours. [22]

Plant remains recovered from more recent roasting pits in Grand Teton National Park indicate that the "wet hay" used to cover the root crops might have been sedge grass or buttercup, which occurs in the wetlands near streams and lakes. The plant remains that were roasted in these pits include a variety of berries, dock, salvia (a leafy sage), ambrosia (a member of the sunflower family), sedgegrass, bistort, and tule or bulrush. These plants require long periods of exposure to moist heat to convert the starches to sugar. Prehistoric people probably also roasted camas roots in these pits, using the same method described by Father De Smet. Camas grows in some of the large meadows on the north end of Grand Teton National Park, near several prehistoric roasting pits. [23]

The records of D. B. Shimkin, the anthropologist who documented much of the Wind River-Shoshone culture during the late 1930s, reveal that these most recent American Indian inhabitants of Jackson Hole traditionally gathered plants for medicine, food, and manufacturing materials. According to Shimkin, individual women or small parties gathered the roots, berries, seeds, pistil, and leaves of a variety of plants. Wild roots, including camas and wild onion, were dug with wooden digging sticks, while currants, rose hips, hawthornes, and gooseberries were picked and then ground with a stone grinding implement. This tool, known as a mano, was usually made of sandstone and used in a back-and-forth rocking motion across another larger flat rock known as a metate [Figure 7]. Berries were also dried and boiled in soup, or mixed with grease and dried meat to form an easily transportable food called pemmican. [24] These food-processing traditions remained unchanged from the Early Archaic period.

|

| Figure 7. Grinding stones (mano and metate) with blue camas bulbs and flowers. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

|

| Figure 8. Early archaic projectile point, Jackson Lake. Final Report on the Jackson Lake Archeological Project, Grand Teton National Park (National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center) |

In addition to the introduction of plant roasting pits, the stone tools found at Jackson Lake also show a cultural change during the Early Archaic period. Spear points from this time period are large with notches on either side of the base, which were used as a way to haft the point to the spear [Figure 8]. Although the use of chert, a stone material, for spear points increased during the Early Archaic period, obsidian continued to be an important raw material. Obsidian spear points from Jackson Lake show a continued reliance on the Teton Pass sources. This demonstrates a strong familiarity with, and possible travel route through, the southern end of the valley.

The number of spear points that date to this time period is low when compared to subsequent time periods. To date, the above-mentioned roasting pit is the only feature from the park that is radiocarbon-dated to the Early Archaic. In addition, archeologists have found no Early Archaic residential structures in Jackson Hole. However, in the nearby basins of Wyoming, Early Archaic people resided in semi-subterranean pithouses. These houses were broad pits dug into the ground and covered with a structure of wood, brush, and hides. An overall paucity of data concerning this time period remains as a gap in the overall understanding of prehistoric life in Jackson Hole.

Middle Archaic Period (5,000 to 3,000 B.P.)

Around 5,000 years ago, prehistoric spear points underwent a notable change. In addition, an increased number of roasting pits date to this era. These changes mark the beginning of the Middle Archaic time period, which extends from 5,000 to 3,000 years ago. The increased density of roasting pits and stone-grinding implements found at Jackson Lake suggests that Middle Archaic people invested more time and energy in processing certain plant foods. The overall increased number of archeological sites across the region also suggests a general population increase, or more frequent travel by these people.

Tipi rings also begin to appear in the archeological record during this time. A tipi ring is a large circle of moderate-sized stones used to anchor a tipi. When the tipi is moved, the stones remain in a circular pattern on the ground. The tipi was made with long poles and covered with animal hides. When the group needed to move, the tipi could be easily dismantled and carried, unlike the more permanent pithouse used in earlier times.

|

| Figure 9. Middle archaic (McKean) projectile point, Jackson Lake. Final Report on the Jackson Lake Archeological Project, Grand Teton National Park (National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center) |

During the Middle Archaic period, a unique type of spear point also appears. Spear points that date to the Middle Archaic do not have side notches, as in earlier times, but have a stemmed base or are lanceolate-shaped [Figure 9]. This new spear point is referred to as McKean, and might represent the influx of a new population into the northwest plains and Jackson Hole. X-ray florescence testing on artifacts from Jackson Lake supports this theory.

Jackson Lake artifacts from the Middle Archaic period show a greater reliance on obsidian for spear points, and a decrease in the use of other stone materials. The most popular obsidian source also changed, from Teton Pass to Obsidian Cliff, approximately 70 miles north. This suggests that people were now entering the valley from the north, and bringing with them this slightly different style of spear point. [25]

This travel pattern, however, is not supported by artifacts found in archeological sites in the Wind River, Gros Ventre and Teton Wilderness areas of the Bridger-Teton National Forest adjacent to Grand Teton National Park. Obsidian artifacts found in these areas reveal that throughout prehistory no major travel corridor existed between the Yellowstone Plateau and Jackson Hole. In these areas, the primary obsidian sources are continually Teton Pass, Wright Creek, and Bear Gulch on the Targhee National Forest. [26] As to whether the new spear point style was brought to the region by an entirely different culture is still debated.

The landscape in Jackson Hole and the surrounding mountains also changed during the Middle Archaic period. The drought-and-fire-adapted species of lodgepole pine, Douglas fir, and aspen gave way to closed forests of pine spruce and fir. These species reflected a shift to the cooler, relatively moist climate, which we continue to experience today. [27]

Late Archaic Period (3,000 to 1,500 B.P.)

|

| Figure 10. Late archaic projectile point, Jackson Lake. Final Report on the Jackson Lake Archeological Project, Grand Teton National Park (National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center) |

The Late Archaic period is well represented in Grand Teton National Park. The disappearance of McKean-style spear points, and the appearance of a point that exhibits distinct notches at the corners generally signal this time period [Figure 10]. The corner-notched spear point came into use around 3,000 years ago, and lasted approximately 2,000 years. During the Late Archaic period, humans continued to hunt large mammals and gather plants. They also continued to use large roasting pits for plant processing. The large number of archeological sites that date to this period in Jackson Hole and in the northwest Plains indicate a population expansion. However, the short growing seasons in these environments probably acted as a controlling mechanism to prevent over population. [28]

X-ray fluorescence testing of obsidian tools dating to the Late Archaic demonstrates a shift back to Teton Pass outcrops as the primary raw material source for Jackson Hole inhabitants. In general, the Late Archaic inhabitants of Jackson Hole used a wider variety of obsidian sources than did any of their predecessors. The travel patterns of this later group, however, closely mirror those of the earliest inhabitants 7,000 years earlier. They had a wide travel range and exploited a variety of obsidian sources ranging from Obsidian Cliff to southeastern Idaho. But, while human use of the valley intensified, the basic lifestyle remained unchanged. Plant gathering and processing, supplemented by hunting, were still the primary activities.

Late Prehistoric Period (1,500 to 500 B.P.)

Around 1,500 years ago, we see the beginning of a period known as the Late Prehistoric, which is signaled by the most dramatic change in subsistence patterns and technology to date. At this time, the bow and arrow replaced the atlatl as the primary hunting weapon. Consequently. projectile points also changed, from large spear points to much smaller ar row points [Figure 11].

|

| Figure 11. Late prehistoric projectile point, Jackson Lake. Final Report on the Jackson Lake Archeological Project, Grand Teton National Park (National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center) |

The bow and arrow significantly changed hunting techniques. It requires much less body movement to shoot a small arrow from a bow than it does to use an atlatl throwing stick to project a large spear. The pull of the bowstring simply requires use of the arm, and the hunter can be standing, seated, or lying. The atlatl, on the other hand, has to be used in a standing position in a considerably open environment and, most successfully, in a situation where the animal is on a driven course or contained in some way. In contrast, a hunter can draw a bow slowly and deliberately, without violent movement or hindrance by underbrush, which allows him to work individually in a variety of environments. [29]

Another significant innovation in the Late Prehistoric period is the use of steatite or soapstone bowls and clay pottery [Figure 12]. Steatite is a soft stone that outcrops naturally in spots along the Teton and Wind River Ranges. This material is soft enough to be carved by an elk antler or other stone tool, and can be hardened by fire and exposure to air. In other areas, such vessels were used for cooking and storage, which was probably also the case in Jackson Hole. As before, Late Prehistoric inhabitants of Jackson Hole also engaged in hunting and plant processing. The number of roasting pits found in the park reached its peak during this period.

The travel patterns of Late Prehistoric peoples changed slightly from that of their recent predecessors. An analysis of obsidian arrow points shows that the most popular sources for obsidian were Teton Pass, Obsidian Cliff, and Targhee National Forest. In general, fewer obsidian sources were used when compared to earlier times, and the use of obsidian sources in southeast Idaho was discontinued. This analysis, coupled with the discovery of the less portable steatite and clay vessels, suggests that the Late Prehistoric inhabitants of Jackson Hole had a much tighter range of travel than earlier groups. They did not range the 175 miles from Obsidian Cliff to Wright Creek as did some earlier populations.

|

| Figure 12. Steatite bowls. Most steatite bowls are 10 to 16 inches high and 8 to 10 inches wide. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

In general, the archeological record reveals little cultural change in the period between 10,000 to 500 years ago. The primary meat sources for mountain-dwelling humans were deer, elk, bighorn sheep, and some bison—while bison and antelope were staples for residents of the Great Plains. In both cases, humans relied on hunting and gathering. There is no evidence to suggest that prehistoric inhabitants of Jackson Hole practiced agriculture or established permanent settlements, as did populations in the southwest and eastern United States. It is important to remember, though, that from the Paleoindian through Late Prehistoric periods, the inhabitants of Jackson Hole and the entire New World were primarily pedestrian. It was not until the first Europeans arrived (around A.D. 1500) that the inhabitants of the New World acquired the horse. In the Rocky Mountains, horses were not widely used by tribes until around A.D. 1700. The arrival of the horse—and the influx of European trade goods such as beads, metals, cloth, and guns—brought about profound changes in the economic and cultural systems of the region.

Protohistoric Period (A.D. 1700 to 1850)

The presence of European goods in the archeological record signals the beginning of the Protohistoric period. This period lasted from around A.D. 1700 to 1850, by which time North American Indian tribes were being relocated to reservations.

Probably the most significant item to be acquired by the tribes was the horse. The introduction of the horse broadened the territories of mounted Indian peoples. The horse increased the mobility of many tribes and brought together the Great Basin and Plains cultures. According to D. B. Shimkin, the introduction of the horse into the Wind River Shoshone culture upset the economic and social balance. Because horses were initially scarce, the men generally rode in order to be fresh for hunting. As a result, women had to walk, which upset the social equilibrium between the sexes. Individuals and families acquired more movable goods, and hunting, gathering and fishing territories changed. The tribes with horses also became more efficient at communal hunting, which allowed them to provide more food for a larger population. At the same time, however, these tribes lost their intimate knowledge of the smaller game species, such as squirrels and rabbits. [30] In and around Jackson Hole, however, early nineteenth-century trappers encountered mountain-dwelling peoples who appeared to be thriving without horses. Trapper and explorer Osborne Russell described an 1835 encounter with mountain-dwelling people in the Lamar Valley of Yellowstone National Park.

Here we found a few Snake Indians comprising 6 men 7 women and 8 or 10 children who were the only Inhabitants of this lonely and secluded spot. They were all neatly clothed in dressed deer and Sheep skins of the best quality and seemed to be perfectly contented and happy—Their personal property consisted of one old butcher Knife nearly worn to the back two old shattered fusees [31] which had long since become useless for want of ammunition a Small Stone pot and about 30 dogs on which they carried their skins, clothing, provisions etc on their hunting excursions. They were well armed with bows and arrows pointed with obsidian. The bows were beautifully wrought from Sheep, Buffaloe and Elk horns secured with Deer and Elk sinews and ornamented with porcupine quills and generally about 3 feet long. [32]

These people lived on berries, herbs, roots, small mammals, and larger game animals such as elk, deer and mountain sheep. Their diet also included native trout and whitefish from the mountain lakes. [33]

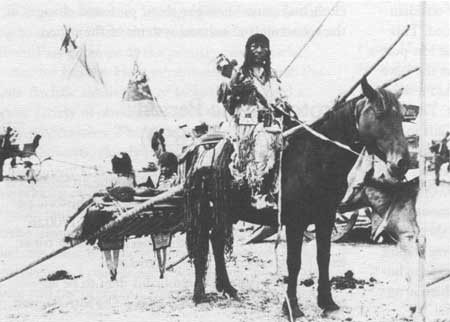

Other nineteenth-century encounters with American Indian peoples in the region describe them as traveling in small family groups. Large dogs, used as hunting and pack animals, accompanied these groups. Often, these dogs pulled a V-shaped travois, used to carry moderate-sized burdens. The travois was made of two long poles; the front tips were attached to a harness at the dog's shoulders, while the ends were left dragging on the ground. Midway up the poles was a frame used to carry burdens such as wood, food, small children, and the sick or elderly [Figure 13]. [34] Therefore, it appears that although the introduction of European trade goods brought about changes in the economic and cultural systems of the plains tribes, the mountain-adapted peoples of Jackson Hole maintained their highly adapted and efficient subsistence strategy.

|

| Figure 13. A travois, shown here being pulled by a horse, was made of two long poles with an attached frame for carrying people and items. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

The Shoshone in Jackson Hole

The first mountain-dwelling peoples encountered by the trappers and early nineteenth-century explorers in Jackson Hole were generally known as the "Sheep-eaters" and were said to have spoken in the "Snake" tongue, which is a reference to the Shoshone. [35] The Shoshone language is part of a large language group known as Uto-Aztecan. Members of this group range from the Northern Plains to the Cascade Mountains and into the southwestern United States to Mexico. [36] It is not certain where the Shoshone got their name, but the earlier-used term "Snake" was likely a misinterpretation of the serpentine hand gesture used to describe the in-and-out motion by which they wove their grass-and-brush shelters. [37]

The term "Sheep-Eaters" described those members of the Eastern Shoshone who subsisted, at least in part, on mountain sheep. The "Tukudika," as they called themselves, remained high in the mountains and were still without horses when they were placed on the Wind River Reservation around 1868. [38] The "Sheep-Eaters" were just one of several specialized groups considered part of the Eastern Shoshone tribe. Other names, such as "Kucundicka" (meaning the "Buffalo Hunters" of the Plains), the "Pa'Iahiadika" or "Elk-Eaters," who hunted the western slopes of the Tetons, and the "Do'yia" or "Mountain Dwellers," who were scattered throughout the mountains of the Yellowstone region, describe members of a single cultural group. Although these groups utilized the mountains and northwest Plains in much different ways, they were all members of one tribe, the Eastern Shoshone. [39]

To the Shoshone, these names did not define a rigid political or cultural division of people. All were one tribe and spoke one language, and their names did not separate individual political or social groups. Instead, they defined ecological niches. For example, the Sheep-Eaters of the Northern Rocky Mountains specialized in hunting mountain sheep, while the Elk-Eaters hunted primarily elk. These individual group names demonstrate the way American Indian tribes, such as the Shoshone, conveyed important information concerning the ecosystem within which they lived. They also offer a clue to the vast and intimate knowledge that these people had of their home land and the species within it. [40]

D. B. Shimkin wrote a similar account of Wind River or Eastern Shoshone demographics. According to Shimkin, during the early 1800s the entire Wind River Shoshone tribe was comprised of 2,000 to 3,000 individuals. During the winter and spring, this tribe split into three to five smaller groups called bands. Each band was made up of 100 or 200 people and occupied a different portion of the Shoshone territory. During the summer, each band divided into individual extended family groups. These family groups might have consisted of 10 to 30 closely related individuals, like the group encountered by Osborne Russell in 1835.

With the coming of the autumn months, the individual family groups reunited with the larger tribe for the annual communal bison hunt in the inter-montane basins and open plains. This hunt was necessary for obtaining and processing dried meat supplies for the upcoming winter. For the winter, the tribe could again divide into smaller bands, each of which resided in a different part of the vast Shoshone territory. [41]

Archeological remains also offer insight into the spiritual bond that the Shoshone and prehistoric peoples had with Jackson Hole. High in the mountains of both the Teton and Gros Ventre Ranges are semicircular stone enclosures. These enclosures, and many like them in the mountains of northwest Wyoming, offer clues to the spiritual importance of these high mountain peaks.

For the modern Shoshone, who continue to maintain close cultural ties to this region, the majestic and snow-capped peaks of the Tetons hold special significance. In the Shoshone belief system, mountain peaks provide access into the spirit world, where they gain special powers for such things as hunting or healing. On these peaks, referred to as "puhadoya," which is translated as "Power Mountain," individuals enter the spirit world through visions or dreams. [42]

According to anthropologist Âke Hultkrantz, who has extensively documented the Shoshone culture, the attainment of power for the ordinary Shoshone individual requires special preparation. Alone and without a weapon, the individual sets out for places known through legend and tradition to be the home of the spirits.

Sometimes he turns his steps towards the hillocks or solitary rocks out on the prairie where the desert puha [powers] generally appear. At other times, he travels to the water where the fish puha may manifest them selves. But most often, he makes his way to the mountains. [43]

During the vision quest, a person remains on the mountain for at least two, and perhaps as many as five days without food or water. While on the mountain, the person dreams and acquires the full power of those dreams throughout the following year. The stone enclosure serves as a bed in which the vision seeker lies during this quest. [44]

The importance of such sites is difficult to impress on a culture that separates religion from the day-to-day activities of life. For the American Indian tribe that is culturally and spiritually linked to Jackson Hole, this separation does not exist. For the Shoshone, all of life—including religion, politics, daily subsistence, the natural environment and the spiritual world—are interrelated and connected by the life sustaining energy or "puha" that flows through all things. [45]

Summary and Conclusions

Although local residents have long been aware that extensive prehistoric sites and a wealth of artifacts can be found throughout Jackson Hole, it has only been during the last 25 years that archeologists have been able to piece together part of the prehistoric record of this area. This record has revealed that prehistoric people lived in Jackson Hole for much of the last 11,000 years. During the earliest Paleoindian period, human populations were generally small and probably occupied the area sporadically. There is little evidence to suggest that humans were in the valley for anything other than hunting and procuring obsidian for their tools until around 5,800 years ago.

During the Archaic periods, the number of archeological sites increases in Jackson Hole. Roasting pits also appear in the archeological record. These findings suggest an increase in the overall population, or an increasingly mobile population. However, it is difficult to use the size of an archeological site to indicate population size, since people probably used the same campsites time and time again.

Although spear point styles and travel patterns changed, hunting and food-processing techniques remained fairly constant throughout prehistory. Even as hunting technology shifted from the atlatl spear-thrower to the bow and arrow, and the horse was introduced to many tribes, Jackson Hole's people continued a hunter-gatherer form of subsistence and lived in relatively small groups. By the time the early trappers arrived, this area was part of the vast territory of the Shoshone tribe. In general, we know that throughout the time period extending from about 1,500 to 11,000 years ago, plants heavily influenced the travel and subsistence patterns of Jackson Hole's prehistoric people. Sites found at high elevation that date throughout the prehistoric continuum, and which are associated with edible plant species, support this model. [46]

D. B. Shimkin's demographic description of the Wind River Shoshone also supports the original archeological model proposed by Gary Wright. The large base camps found along the shores of Jackson Lake could well represent the locations where a band of individuals camped during the spring and early summer. Smaller sites found in the canyons and higher alpine meadows could represent the individual family camps. Consequently. the overall population residing in Jackson Hole at any given time would have been relatively small and on the band—rather than tribal—level. During the summer months, this group would disperse into family groups throughout the mountains surrounding Jackson Hole. However, recent findings have revealed that obsidian, other raw material sources, topography, and spiritual pursuits also guided the travel patterns of American Indians. These cultural necessities were not addressed in the original predictive archeological model proposed by Gary Wright and his colleagues.

Clearly, there are many unanswered questions about the prehistory of Grand Teton National Park and Jackson Hole. It is still unknown what types of living structures were used within the park through much of early prehistory. There also remain questions about the different adaptive strategies for the northern and southern parts of the valley. Future archeological investigations within the park and surrounding areas will continue to evaluate and reconstruct models of adaptation and, perhaps, lead to new theories and a better understanding of the cultural and spiritual lives of the earliest people of Jackson Hole.

Notes

1. The Lawrence Collection is currently housed in the Jackson Hole Museum and Teton County Historical Society in Jackson, Wyoming.

2. Gary Wright, Susan Bender and Stuart Reeve, "High Country Adaptations," Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 25, No. 89, p. 181.

4. Stuart Reeve, "Lizard Creek Sites (48TE700 and 48TE701): The Prehistoric Root Gathering Economy of Northern Grand Teton National Park, Northwest Wyoming" (Lincoln NE: National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center 1983).

6. Gary A. Wright, "The Shoshonean Migration Problem," Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 23, 1978, pp. 117-120.

8. Gary A. Wright, People of the High Country: Jackson Hole Before the Settlers (New York: Peter Lang, 1984).

9. Within the boundaries of the National Elk Refuge in Jackson, Wyoming, lies the Goetz site. Although never extensively excavated, this site reveals bison bone in association with prehistoric tools, suggesting that it is a butchering or kill site. The radiocarbon date from this site suggests that the site is 1,480 years old. Older style points are reported to have come from this site as well. Although this site has not been properly recorded and tested to today's archeological standards, it does demonstrate that bison was present in the prehistoric diet of Jackson Hole residents. See Charles Love, "An Archaeological Survey of Jackson Hole Region, Wyoming," M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Wyoming, Laramie, 1972.

10. Christy G. Turner II, "New World Origins," Ice Age Hunters of the Rockies, ed., Dennis Stanford and Jane S. Day (Denver, CO: Museum of Natural History Press, 1992), p. 8.

11. Cathy W. Barnowsky, "Late-Quaternary Vegetational and Climatic History of Grand Teton National Park and Vicinity," Jackson Lake Archeological Project: The 1987 and 1988 Field Work, Melissa A. Connor, et al. (Lincoln, NE: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center, 1991), p. 26.

12. George Frison, Prehistoric Hunters of the High Plains, 2nd edition (New York: Academic Press, 1991), pp. 211-212.

14. Charles M. Love, "An Archeological Survey of the Jackson Hole Region," p. 96.

15. Connor, et al., Jackson Lake Archeological Project.

16. Melissa A. Connor and Raymond Kunselman, "Mobility, Settlement Patterns, and Obsidian Source Variation in Jackson Hole, Wyoming," unpublished paper presented at the Second Biennial Rocky Mountain Anthropological Conference, Steamboat Springs, Colorado, September 27-30, 1995).

17. George C. Frison, "The Foothills-Mountains and the Open Plains: The Dichotomy in Paleoindian Subsistence Strategies Between Two Ecosystems, Ice Age Hunters of the Rockies, ed., Dennis J. Stanford and Jane S. Day (Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1992), p. 323.

21. Brian M. Fagan, World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1979).

22. Hiram Martin Chittenden, The Yellowstone National Park Historical and Descriptive, 5th edition (Cincinnati, OH: Robert Clarke, 1905), p. 387.

23. Stuart Reeve, "Lizard Creek Sites (48TE700 and 48TE701): The Prehistoric Root Gathering Economy of Northern Grand Teton National Park, Northwest Wyoming" (Lincoln, NE: National Park Service, Midwest Archeological Center 1983).

24. D.B. Shimkin, "Wind River Shoshone Ethnogeography," Anthropological Records, Vol. 5, No. 4.

26. James R. Schoen, "High Altitude Site Locations in the Bridget Gros Ventre and Teton Wilderness," paper presented at the Third Biennial Rocky Mountain Anthropological Conference, Bozeman, Montana, September 18-21, 1997.

31. A term applied to smooth-bored, flintlock guns traded to American Indians primarily by the Hudson's Bay Company. They were usually shortened for ease of handling on horseback. The word is probably a corruption of the French fusil, which itself probably comes from the Italian fucile, a flint. These guns were vastly inferior to the rifled guns of the trappers in range and accuracy. Osborne Russell, Journal of a Trapper, ed., Aubrey L. Haines (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), p. 157, no. 25.

34. Ella Clark, Indian Legends from the Northern Rockies (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), pp. 11-12.

36. Virginia Trenholm and Maurine Carley, The Shoshonis: Sentinels of the Rockies (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), p. 3.

39. Ake Hultkrantz, "The Shoshones in the Rocky Mountain Area," Annals of Wyoming, Vol. 33, April 1961, 34; and Adamson Hoebel, "Bands and Distributions of the Eastern Shoshone, American Anthropologist, Vol. 40, No. 3, 1938, p. 410.

40. Julian Steward, "Some Observations of Shoshonean Distributions," American Anthropologist, Vol. 41, 1939, p. 262.

42. Deward Walker Jr., "Protection of American Indian Sacred Geography." Handhook of American Indian Religious Freedom, ed., Christopher Vecsey (New York: Crossroads Publishing, 1993), p. 104.

43. Âke Hultkrantz, Belief and Worship in Native North America (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1981), pp. 34-35. Italics original.

44. Julian Steward, "Culture Element Distributions," XXIII Northern Gosiute Shoshoni, Anthropological Records, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1945), p. 282.

45. Sherri Deaver, "American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) Background Data" (Billings, MT, Bureau of Land Management, 1986), p. 78.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grte/hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2004