|

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 9:

Life On the Homestead

Charles Shinkle filed preemption papers on a 160-acre parcel north of Kelly in 1910. His final testimony of proof for Homestead Patent 715943 (1918) documented his setbacks:

1911 2 acres veg. cattle got it. 1912 3 acres 1/2 acre veg. 1 ton. 1913 No crop 1914 No crop too dry. 1915 3 acres cattle got it. 1916 3 acres 1 a. veg. 1/4 ton veg.

|

| The Cunningham cabin was a typical Jackson Hole homestead. The "dogtrot-style" log cabin has a sod roof. National Park Service |

Anyone who has enjoyed or endured—depending on one's viewpoint—a winter in Jackson Hole might wonder what possessed settlers to believe they could cultivate crops in this valley. Nevertheless, homesteaders believed it—and grew crops here. The overwhelming majority adopted mountain-valley ranching, which dominated the economy of Jackson Hole until the tourist industry gained predominance after the Second World War. [1] Few contemporary accounts of settlement in Jackson Hole exist, and available sources shed little light on the homesteaders' frontier. Reminiscences are found in oral history tapes, newspaper accounts, or memoirs. However, care must be exercised in using these sources, for hand-down stories become embellished and memories are notoriously inaccurate. But, coupled with records such as homestead patent files and knowledge of the homesteaders' frontier in America, reasonable inferences can be made about settlement in Jackson Hole.

For much of the nineteenth century, Americans shared a general perception of the plains west of the Mississippi River as a barren desert. The myth of the Great America Desert persisted through the Civil War. But in 1847, Mormons emigrated to the Great Basin, successfully farming land that appeared impossible to cultivate, and proved the feasibility of agriculture in the arid West. In addition, after the Civil War, open-range cattle ranching prospered on the native grasses of the Great Plains. [2]

These events made two things clear. First, the hunter-woodsmen-farmers of the Old Northwest and Mississippi Valley would have to adapt their agricultural lore and experience to a very different environment. The open-range cattle industry represented such an adaptation. Second, technology could be applied to manipulate the environment, such as the Mormons' construction of an impressive system of canals. After the Civil War, technological improvements enabled homesteaders to cultivate lands where once the possibilities seemed remote. Barbed wire, patented in 1874, provided the practical material for fencing fields on the Great Plains. Also, rapid improvements in farm machinery answered the demand for ways to cultivate the larger acreages needed to earn a living in the West. For example, the plow, which evolved rapidly after 1865, enabled farmers to turn over prairie soils more efficiently. By 1873, manufacturers produced no fewer than 16 effective plows in the United States. [3] Acreage was another consideration. East of the Mississippi River, 80 acres were more than enough to support a family adequately. This was not the case in the West, where less rainfall required 300 or more acres for family farms in most instances. Ranches required thousands of acres, both for grazing and cultivating winter feed. In exceptional cases, a family could earn a good living off 40-60 acres of well-irrigated land in some areas of the West. [4]

The farmer's frontier slowly penetrated the Great Plains in the 1870s and 1880s, creeping to ward the Rockies from the east. From the Salt Lake Valley, Mormon settlers expanded into adjacent areas such as Idaho. Homesteaders first settled in the Teton Basin in Idaho in 1882. In 1887, a drought parched much of the West. The dry weather cycle hit the Great Plains especially hard, as homesteaders faced ruin as crop after crop failed. To compound the problem, the Midwest and foreign countries produced bumper crops, which kept farm product prices drastically low. This resulted in a decade of serious economic and social disruption. Farmers in western Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Colorado suffered the most; it is estimated that an astonishing one-third to one-half went bankrupt. In western Kansas and Nebraska, 100,000 people left their homes. Ghost towns, forlorn and empty, dotted the stark landscape of the high plains. Economic depression, beginning with the Panic of 1893, gripped the nation for five years, complicating the farmers' dilemma. The Populist movement swept the agrarian West in these years as leaders such as Mary Elizabeth Lease urged farmers to "raise less corn and more hell." This was the backdrop of events when settlers breached the mountains to homestead in Jackson Hole. [5]

Shelter was the primary concern of the arriving settlers and, like the earliest colonists, people on the frontier used the materials provided by nature. On the Great Plains, where wood was scarce, the sod house symbolized the homesteader's frontier. In Jackson Hole, abundant lodgepole pines provided convenient materials for log cabins, the predominant shelter in Jackson Hole, even after the first sawmills appeared in the valley. Most people started out with small one and two-room cabins, which seldom exceeded 18 x 24 feet in dimensions. The dogtrot was a common type, consisting of two cabins joined by a covered breezeway or porch. The Cunningham cabin is a good example of this construction. Builders joined the corners with saddle notches, or squared corners fastened with spikes. Cracks between the logs were daubed with a dirt mortar often reinforced along the bottom with willow wands. Roofs consisted of sapling poles covered with dirt. At first, floors were packed dirt, but settlers installed rough board floors as soon as logs could be sawed by hand, or when the first sawmills provided a ready supply of lumber.

The Budge cabin, built southeast of Blacktail Butte in 1897, was a one-room sod-roofed cabin with one door and one window. The younger Jim Budge recalled water and mud leaking through the roof during rainstorms. To keep the children dry, Mrs. Budge placed them under the kitchen table and covered it with oilcloth. [6] Frances Judge described the small homestead cabin constructed shortly after the turn of the century for her grandmother, Mary Wadams. Judge remembered the cabin as a small sod-roofed dwelling with a "brushed earth floor that had been dampened and swept until it was as hard as cement." Mrs. Wadams tacked white muslin cloth on the ceiling to reflect more light in the cabin and catch dirt from the roof. The interior walls were insulated with pages from old magazines. Rodents were a persistent problem, because there were so many entries. Judge recalled how common it was to see the moving depression of a mouse scurry across the muslin ceiling. Her grandmother prepared a flour paste laced with strychnine to control the rodents. [7] Joe Jones filed on a relinquishment south of Blacktail Butte in 1907, which included a cabin abandoned by the first occupant. When the Jones family arrived, they found that cattle had entered the structure, causing considerable damage to the floor. Joe Jones simply pulled up the boards and turned them over. [8]

As time passed and families grew, homesteaders added on to the original cabin or constructed more elaborate residences. Typical was the whitewashed cabin at Menor's Ferry, which had two distinct additions. By 1904, Jim Budge had added two rooms to his cabin to accommodate a growing family. In 1914, Norm Smith built an addition to provide room for his very large family. The Jim Williams cabin at the Hunter Hereford Ranch has two large wings added in later years. [9] An old photograph of the James and Lydia Uhl residence shows a large cabin with multiple rooms. The R. E. Miller residence, which is extant on the elk refuge, was built after 1892, but prior to 1900. (The W. O. Owen Survey Map of 1892 shows the first Miller cabin located north of the present building.) J. E. Stimson captured the interior of the Miller house; the image shows an affluence not common in Jackson Hole. Pierce Cunningham built a larger house after 1900 north of his first cabin. In 1914, Cunningham's neighbor, Emile Wolff, cut logs for a new and larger home. Bertha Moulton recalled that she and her husband John lived in a small log cabin for the first 17 years of their marriage. They built a pink stucco residence around 1934. [10]

Sawmills provided much-needed lumber for floors, roof, sheathing, and window and door frames. Stephen Leek is credited as the first to introduce a sawmill. He hauled a water-powered mill into the valley from Market Lake, Idaho, in 1893 and set it up on Mill Creek near Wilson, Wyoming. Other sources claim the Whetstone Mining Company hauled a mill into the north end of Jackson Hole around 1889. It is possible that Leek acquired this mill after the failure of the mine. [11]

At any rate, there was at least one sawmill in the valley by 1900, operated by Bonnie Holden for eight months of the year. By 1909, no fewer than three sawmills existed at the south end of the valley. Struthers Burt recalled two active sawmills in Jackson Hole when he and Carncross began constructing the Bar BC in 1912-1913. He recorded the disparaging complaint of one resident, who described the area as "a country where a 12-inch board shrunk an inch a year for 15 years." Lumber could be ordered in advance, but it did not matter much as you took what was delivered and "thanked God for it." Burt called some of the lumber "wanie-edged," a description for boards cut so close to the edge of the log that the bark showed and the board tapered off at one end. Sometimes the edge of a board measured two inches at one end and gradually narrowed to nothing at the other end. The frame addition on the Menor Cabin, built before 1900, suggests that lumber was available. Since, so far as is known, the original roofing on the cabin was board, it implies that lumber was sawn commercially in the valley by 1894, possibly at Leek's water-powered mill. After 1900, frame structures became more common on ranches and farms. In 1919, J. D. "Si" Ferrin set up a water-powered mill to saw lumber for large frame buildings at the Elk Ranch. [12]

Contrary to popular perceptions of sturdy pioneers who secured all they needed from the land, homesteaders in Jackson Hole imported building materials—notably nails, glass, door frames, window frames, and roofing paper. At first, settlers freighted these supplies into the valley from distant communities such as Market Lake and Rexburg, Idaho, but building materials and hardware became available locally when Pap Deloney opened his general mercantile store in 1899. [13]

Thus, using local materials, such as lodgepole pine, and imported hardware and building supplies, settlers developed their farms and ranches. What did a typical homestead look like? The final proof papers of entrants offer some clues, although the detail of descriptions in records varies considerably. Furthermore, desert land entries did not require occupancy, therefore structures were not listed on desert entry papers.

|

| Albert Nelson settled in the Kelly area in 1904. His homestead included a log house, shed, storehouse, stables and other improvements. National Park Service |

The earliest settlers on Mormon Row and the Gros Ventre established small cattle ranches. At the present Kelly townsite, Albert Nelson constructed an 18 x 24-foot log house with a shingle roof, a log storehouse, a log living room, a shed, and stables by 1904. North of the Nelson place at Kelly Warm Springs, William Kissenger constructed a 16 x 20-foot log house with three rooms, a log stable, and a log shed. [14]

Southeast of Blacktail Butte at Mormon Row, Jim May had completed a five-room cabin and stables by the time he filed final proof papers in 1901. T. A. Moulton completed a new frame house in 1915. Other structures included a cabin, a granary, a stable, and a hoghouse. The granary suggests he cultivated grain, possibly 90-day oats. Jake Johnson settled on his land in 1909 and built a three-room frame house, two log stables, a storehouse, a root cellar, a hen house, and a granary. Andy Chambers homesteaded a tract in 1912; by 1916, the farmstead consisted of an 18 x 20-foot log house, a 16 x 16-foot stable, and one new dwelling, partially built. The Woodward house was a substantial 20 x 32-foot, one-and-a-half-story log house, consisting of five rooms. It had a stone foundation and a shingle roof. The Harthoorn place consisted of a one-room log house, one incomplete seven-room log house, two log granaries, a large two-story log barn, a hen house, two cellars, and a log machine shed, which became more common with mechanization of farming. [15]

On Antelope Flats, Joe Pfeifer took up a homestead in November 1910 and proved it up with a two-room log home, a barn, and other outbuildings. East of Pfeifer's place and north of Ditch Creek is a hull known as Aspen Ridge. James R. Smith homesteaded the Aspen Ridge Ranch in 1911; by 1916, he had constructed a three-room log dwelling, a log hen house, a cellar, a log barn, and a frame granary. One-half mile east, James Williams homesteaded the Hunter Hereford Ranch, building a square-shaped log cabin and a small horse stable. Just south of Ditch Creek, Ransom "Mickey" Adams took up a relinquishment in 1911 that is the present Teton Science School. Adams built a four-room house, a large two-story barn (18 x 56 feet), a storehouse, a large cattle shed, a shed, a chicken house, a granary, an ice house, and a spring house. One building at the school may date from this period. [16]

On the west side of the Snake River, James Manges built a cellar, smokehouse, barn, stable, and woodshed by 1917. He also built an unusual one-and-one-half story log cabin with four rooms. (This building exists today, although modified.) In this area, homestead structures were similar to those near Blacktail Butte, except that none had granaries, indicating that cultivation was restricted to growing hay.

South of Menor's Ferry, homesteaders tried to establish farms and ranches along the narrow strip of land between the Snake River and the moraines and benches at the foot of the Teton Range. Charles Ilse homesteaded the meadow flat just north of Stewart Draw in 1910. His buildings included a two-room log and frame residence and a root cellar. In 1914, William Grant filed an entry next to Ilse. He constructed a seven-room log-and-frame house, a barn, and a chicken house. In the late 1920s, wranglers Shadwick Hobbs and Lewis Fleming filed stock-raising entries south of the JY Ranch. Although they were never developed into full-scale working ranches, their homestead cabins still exist. The Fleming cabin is now the Lower Granite Canyon patrol cabin, while Hobbs's "Starvation" cabin is located on Granite Creek, south of the Granite Canyon Trail. Neither homestead appears to have been developed. Lewis Fleming died in 1926, while Hobbs never established a working ranch headquarters at his cabin. [17]

In the Spread Creek-Buffalo Fork area, more homesteads were devoted to cattle ranching. In 1904, the Uhl ranch consisted of a house, store house, shop, spring house, wagon house, smoke house, stables, and sheds. Pierce Cunningham had built a house, stables, and sheds by 1904. Later homesteads in this area were very similar. Otto Kusche homesteaded what later became the headquarters of the Elk Ranch; he built a house, barn, storeroom, and cellar. None of the present structures at Elk Ranch are associated with Kusche's homestead. Si Ferrin began the nucleus of his short-lived ranching empire in 1908; with his wife and ten children, he constructed a residence, barns, and other outbuildings. In 1911, Gottfried Feuz settled on 160 acres with his wife and seven children. By 1917, his homestead consisted of a log house (18 x 36 feet), store house, stable, cattle shed, two hen houses, and cellar. [18]

|

| Andy Chambers homesteaded a tract on Mormon Row in 1912. By 1916, the farmstead included this 18 x 20-foot log house. Arnold Thallheimer |

Based on records, the typical homestead in Jackson Hole consisted of a two-room house, usually built of logs. Frame dwellings were more common after 1900. Barns, stables, and storehouses were common outbuildings at both ranches and farms. Granaries and cellars suggested an emphasis on farming, rather than cattle ranching. Everyone tried to live with a relative degree of self-sufficiency. A number of settlers built smokehouses to cure wild game, especially elk. Hen houses indicate the importance of poultry. Hoghouses were much less common, but some settlers kept pigs for personal consumption and, perhaps, sale.

Along with remnant cabins, the buck-rail fence has come to symbolize the homesteaders' frontier in Jackson Hole. Also referred to as a buck-and-pole, buck-and-rail, or four-pole leaning fence, it was the dominant fencing in the first years of settlement, simply because lodgepole pine provided a ready supply of material. The myth prevails that settlers used this type of fence because it requires no post hole, resting instead on the crossed bucks at each end of the panel. Pioneers reputedly preferred this fence because digging holes in the cobble-laden soils of Jackson Hole was back-breaking work. This is not true. Digging post holes is hard work, but so is cutting and hauling lodgepole pine. A buck-rail fence represented a considerable investment of time and labor. After 1900, barbed wire was introduced in the valley and became the dominant type of fence. If settlers described fences in their proof papers, as often as not they installed "post and 3 wire fence." Homesteaders who continued to construct buck-rail fencing may not have possessed the capital to purchase barbed wire. John Moulton's homestead was typical of many. He constructed a buck-rail fence around his residence, but closed off most of his farm with barbed wire. He recalled that some neighbors objected to the barbed wire, fearing it would injure livestock. If there was concern, it was short-lived, for most of the homesteaders on Mormon Row installed barbed-wire fences.

Occasionally, variations appeared such as a two pole two-wire buck fence, a modified buck-rail fence that used barbed wire. Post-and-wire fences were sometimes topped with a pole spiked into the posts. These are good fences to use in wildlife migratory routes, for ungulates such as elk and deer can jump them easily without much danger of entangling themselves in the barbed wire. By the 1920s, steel fence posts made their appearance. [19] The buck-rail fence appears frequently in scenic photographs of the park, and their rustic appeal is apparent. However, a post-and-wire fence was more practical for farmers and ranchers. They cost less, took less time to put up, and required less maintenance. The buck-rail fence regained popularity in the 1920s because of its aesthetic appeal, as dude ranches and tourist facilities became more predominant.

Residing for five years on a 160-acre tract was one major requirement of the Homestead Act of 1862; the law also required the entrant to cultivate the land. Most settlers established small cattle ranches and cultivated hay for winter feed. Farmers grew grain crops, primarily 90-day oats that were suitable for areas like Mormon Row. Elevation and climate combined to restrict the growing season for crops. The valley has an average of 60 frost-free days per year. Cyclic weather patterns such as severe winters or occasional droughts prove even more disastrous in a country with such a short growing season.

According to local tradition, John Cames was the first settler to farm in the valley. He packed dismantled farm machinery to his Flat Creek homestead and probably cultivated native hay. Stephen Leek planted the first domestic grain in the valley at his South Park ranch after 1885. Prior to becoming a rancher, J. D. "Si" Ferrin homesteaded on Twin Creek in the present elk refuge in 1900, where he reportedly proved that oats, wheat, and barley could be raised in the valley. This is a questionable claim, as several homesteaders testified to having planted oats prior to 1900. For instance, Frank Sebastian reported growing 20 acres of oats in 1899. Ferrin may have been the first to raise wheat and barley in the valley. One source claims that Ferrin harvested the first oats as grain in 1902, producing 5,000 bushels. This may be true, as ranchers often harvested oats as hay, rather than risk losing the crop in an attempt to allow the oats to mature. [20]

People raised hay and grain to feed livestock. They cultivated brome grass, timothy, alfalfa, and alsike (a European perennial) clover for hay, and raised barley and oats for both grain and hay. Farmers grew wheat later, but the climate, as well as the lack of a mill, prevented wheat from becoming a dominant crop. [21] Striving to be self-sufficient, most settlers grew garden crops for personal consumption. Potatoes, carrots, turnips, cabbage, rutabagas, onions, peas, beets, radishes, lettuce, and some berries were popular crops. A few settlers raised enough potatoes to sell locally.

After providing a shelter, clearing land became the most important task. Clearing sagebrush was one of the most reviled but necessary chores confronting settlers. If possible, savvy homesteaders filed on land with convenient access to water, and then cut a ditch to the field in order to flood it. Flooding killed the sagebrush and made it easier to clear. Fire was also used to clear fields, but this had to be employed with care. The Courier reported farmers busily backfiring grasses in the Aspen Ridge area in 1914, presumably to clear land. There is little available information to determine the extent to which these methods were employed. Grubbing sagebrush—pulling it by hand—was the most common practice. Settlers plowed the soil to loosen roots, grubbed the sagebrush, then stacked and burned it.

Otto Kusche of the Elk Ranch testified that "each year I have grubbed and cleared land which I have need for pasturing my own stock." Between June 1909 and October 1915, Kusche managed to clear a meager 13 acres and seed it to alfalfa. A neighbor, Anton Grosser, cleared ten acres, complaining that his 160-acre tract was "practically covered with willows and aspen brush and is hard to clear." In five years devoted to proving up homesteads, it was common to clear and plow three to seven acres the first season, and perhaps expand to 35 or 40 acres by the fifth year. Other environmental factors hindered the clearing of fields. The soils of Jackson Hole are predominantly glacial deposits and, consequently, the valley floor is covered with quart-zite cobbles, commonly the size of large potatoes. Parthenia Stinnett, the daughter of P C. and Sylvia Hansen, recalled clearing cobbles from fields as one of her childhood chores—and not with much fondness. In isolated cases, environmental changes, perhaps natural or induced by man's activities, damaged fields. Martin "Slough Grass" Nelson sold his homestead to Mose Giltner in 1898 because his land on Flat Creek had become so swampy. Sixteen years later, Giltner attempted to drain the swamp by using a dredge. [22]

|

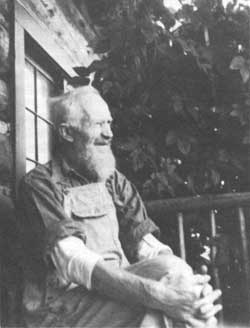

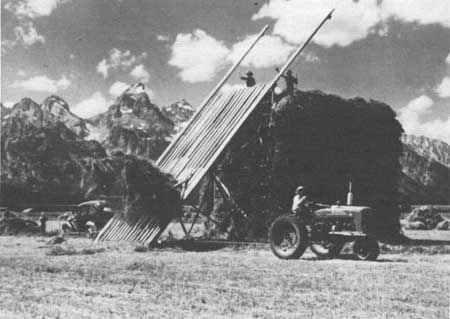

| Jim Chambers stacking hay, 1956. Hay and oats for livestock feed were among the most commonly cultivated crops in the valley. Most farmers practiced alpine valley ranching, grazing their small herds on public lands in the summer, and feeding them hay in the winter. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

As stated in an earlier chapter, settlers turned over at least 5,200 acres of land in and adjacent to today's park. This figure is based on claimants' testimonies for nearly 300 homesteads. They undoubtedly cultivated more acreage later, but it is important to understand that very few were lucky enough to locate a 160-acre tract on which all acreage could be farmed. Terrain, access to water, and vegetation were limiting factors. For example, Will Steingraber estimated that only 100 acres of his 160-acre parcel on the Buffalo Fork were suitable for agriculture. Norm Smith was fortunate, because he could cultivate fully 135 acres of his 159-acre homestead. Johnny "High-pockets" Rutherford believed he could cultivate his entire 160 acres on Antelope Flats, even though he managed to break only 16 acres in five years. Jim May, on Mormon Row, found only 65 acres of his land to be cultivable. Along the upper Snake River near Moran, Roy Lozier believed he could farm 150 of 160 acres, even though he claimed 12 acres of timber on the land. [23]

Virtually all settlers cut irrigation ditches to their land and secured water rights approved by the State of Wyoming. These rights were attached to most farms and ranches. Homesteaders constructed ditches with hand labor, sometimes individually, but most often in partnership with one or several neighbors. James I. May cut a ditch, three miles long, from Ditch Creek to his homestead using a plow and team of horses. May and Jim Budge diverted water from the Gros Ventre to their desert entries, cutting another three-mile ditch. In most instances, farmers and ranchers needed irrigation systems to raise crops on their land. Moreover, the Desert Land Act required that desert entries be irrigated to secure title to the land. [24]

After clearing the land and providing water, what did settlers cultivate? Fred Lovejoy located a 160-acre homestead along the Gros Ventre in 1899, where the campground is located today. In five years, he irrigated a ten-acre meadow and cultivated 12 acres in three seasons, presumably hay. He also raised a small vegetable garden. After 1900, Lovejoy added a 160-acre desert entry, cutting a main ditch and one lateral that irrigated 25 acres. He raised oat hay and timothy. In 1903, his 25 acres of oats produced a mere one-quarter ton of hay per acre, the kind of season that bankrupts farmers. Lovejoy explained that he "would have produced more but it was destroyed by gophers and squirrels [sic]." Presumably, he referred to pocket gophers and Uinta ground squirrels. His wife, Mary Lovejoy, added a desert entry in 1908, irrigating 45 acres with water diverted from the Gros Ventre via a three-and-one-half-mile ditch. Her share of the water amounted to four cubic feet per second. By 1913 she had planted 45 acres of wheat and oats, expecting to thresh 1,000 bushels of grain in the fall. The Lovejoys owned a 640 acre ranch by 1916, suggesting that even well-irrigated homesteads of 160 acres were insufficient to provide a decent living in Jackson Hole. [25]

Just west of today's Kelly, Nels Hoagland, a widower, struggled to start a farm. Filing on a regular homestead entry and a desert entry in 1897, Hoagland testified that he had raised no crops on his homestead until 1903, when he managed to complete a ditch. Likewise, it took four years to divert water from the Gros Ventre via a two-and-one-half-mile ditch to his desert entry and no crop had been planted as of 1901. This is a long time to go without producing crops, and may well have wiped out Hoagland's savings, if he had any. At the Kelly townsite Bill and Sophie Kelly established a cattle ranch of 40 acres in 1910. Kelly added a 120-acre desert entry in 1911. He then cut a ditch from the Gros Ventre, cultivating 20 acres of wheat on the property. In 1917, Sophie Kelly filed a 320-acre desert entry south of the Gros Ventre in today's elk refuge. Although she failed to bring water to the tract, she grazed livestock on it for five years and the General Land Office approved her patent. [26]

Ransom "Mickey" Adams homesteaded a 160-acre tract that encompasses the present Teton Science School. In five seasons, he cultivated the following crops: 1912: 20 acres, barley and alfalfa; 1913: 45 acres, oats and barley, which produced 30 tons of hay; 1914: 40 acres, oats and barley; and 1915: 48 acres, oats, barley and alfalfa. His neighbor to the north, Jim Williams, excavated a ditch that irrigated 100 acres. In five seasons he cleared from 8 to 17 acres, planting oats, barley, and alfalfa. [27]

East of Blacktail Butte, farmers rushed to claim homesteads after the presidential proclamation of 1908 opened lands to settlement. Farming, rather than large-scale cattle ranching, dominated this area. In five seasons, Jacob Johnson cleared and cultivated 110 acres, raising oats and potatoes and 30 head of livestock. In 1912, John Woodward preempted 160 acres in the Mormon Row area, hoping to provide a living for his wife and nine children. In the first season, the family raised a garden on one-and-one-half acres. Between 1913 and 1918, Woodward increased cultivation from 11-and-one-half acres to 35 acres, raising oats, hay, and vegetables. A ditch is not mentioned, but one runs through the homestead site. For domestic use, Woodward excavated a well, digging 98 feet to hit water. This was typical on Mormon Row, where most wells were dug to a minimum depth of 90 feet. In contrast, settlers could hit water at depths as little as 12 feet near rivers. Andy Chambers expanded his fields from 11 acres to 40 acres between 1914 and 1916, producing 1,260 bushels of grain in 1916. Chambers may have dry farmed his land, because he did not list a ditch among his improvements. [28]

On Antelope Flats, homesteaders also tried to establish farms. Between 1911 and 1914, Joe Pfeifer cleared and cultivated 20 acres, raising barley, oats, wheat, and a garden. In 1915, he dug a well to a depth of 104 feet, but it was so dry that he had to use a sprinkler to settle the dust. Pfeifer gave up on the well, deciding to use it for a root cellar. He hauled water for domestic use from Ditch Creek. On the bench where the Blacktail Ponds Overlook is located today, a young man named Henry Gunther took up a relinquished homestead in 1914. He cultivated 66 acres of oats and hay by 1917. The Mining Ditch encountered by Frank Bradley of the Hayden Survey in 1872 ran across Antelope Flats. Settlers repaired and expanded the ditch to provide water for their farms. [29]

Similar patterns were followed on the flats south and west of Blacktail Butte and the Snake River. If at all possible, farmers and ranchers diverted water from the Gros Ventre or Snake Rivers or Ditch Creek to irrigate their fields. Richard Mayers filed a desert entry in 1902, adding 166 acres to a homestead entry at the present Gros Ventre Junction. He irrigated five acres with a ditch and four laterals, but the river flooded the area, inundating his fields for three months. By 1906, he had cleared 22 acres, planting alfalfa and barley. Roy Nipper filed on a relinquishment in May 1915, west of Blacktail Butte. He irrigated the land with a six-mile ditch, cultivating 70 acres of oats, barley, and alfalfa by 1919. [30]

|

| The winters in Jackson Hole were, and still are, harsh. This 4-horse team and wagon served as the mail stage on Antelope Flats: Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Across from the Bill Menor homestead, Holiday Menor homesteaded 160 acres on the east bank of the Snake River in 1908. In the first season, he cultivated 20 acres of wheat and barley, harvesting 25 tons of grain hay. The next year, he expanded his field to 40 acres, raising wheat and barley that he threshed, producing 350 bushels of grain. He cleared more acreage until 1912, when he cultivated 80 acres of wheat and barley, and threshed 1,200 bushels of grain. From 1912 to 1918, Holiday Menor raised wheat, barley, and alfalfa on his farm, producing an average yield of 900 bushels of grain and 35 tons of hay. Since Menor did not list a ditch among his improvements, and because there is no ditch on his land, he probably dry farmed. [31]

Agriculture was less important west of the Snake River. Jimmy Manges cleared 42 acres between 1911 and 1917, raising barley, timothy, and wheat. By the time Manges sold most of his acreage to Chester Goss and the Elbo Ranch partnership in 1926, he had little to show for 15 years of work. He sold 115 acres to Goss for $6,325, more money than he had ever seen in his life. [32] Charles Ilse and William J. Grant irrigated and cultivated their homestead south of Sawmill Ponds on the Moose-Wilson Road. Ilse grew 12 acres of timothy, which produced a mere one and one-half tons per acre. Billy Grant raised a two-acre garden and 20 acres of clover, timothy, and grain hay. He irrigated 94 acres. [33]

Moritz Locher filed an entry on a relinquishment just south of Jenny Lake in 1915. In two years he managed to plow only 18 acres, when he perished in a freak accident. Skiing across the flats north of Timbered Island, Locher broke his ankle and, unable to move, died of exposure. After his starved dog turned up at the Bar BC, rescuers searched for him, but snowstorms had obliterated his tracks and covered his body. The spring thaw revealed his corpse. His heirs plowed and planted 22 acres of wheat in 1922 and cut a quarter-mile ditch, but "harvested nothing." In 1921, Ed K. Smith homesteaded another relinquishment adjacent to the Locher property. Nicknamed "Roan Horse" or "Roany" Smith, he intended to breed and raise horses. However, since he was 54 years old at the time, it was more likely a retirement home. Smith testified before the 1933 Senate Subcommittee hearing in Jackson Hole. When asked what he did for a living on his homestead, Roany Smith replied, "We worked for the Forest Service when we felt like it, fished when we felt like it, and worked on the homestead when we felt like it." [34]

In the Buffalo Fork-Spread Creek area, settlers tended to raise hay and cattle. With the aid of irrigation, Charlie Hedrick cultivated 40-50 acres of hay on his homestead. Hedrick's neighbor, Rudy Harold, broke 40 acres between 1910 and 1915, raising timothy. He dug a well, and struck water at 18 feet, a sharp contrast to the 100-foot-deep wells on Mormon Row. At two homesteads which became the Triangle X, John Fee Jr., and William Jump filed entries in 1909. Fee irrigated and raised 30 acres of native hay, producing one and a quarter tons per acre. Jump cultivated much less, a trifling seven acres of oats for about 13 years. Orin Seaton built a home in 1909 and moved his wife and three children to the ranch in 1910. By the time he filed his final proof papers in 1913, he had fenced and irrigated 82 acres, raising hay. [35]

Along the Buffalo Fork in 1909, Walt Germann irrigated his land, cultivating six acres of barley the first season, and expanding to 20 acres of clover, alfalfa, and oats two seasons later. East of Germann, John Smejkal, a Bohemian immigrant, homesteaded in 1911. Clearing ten acres in 1912, he gradually expanded his fields to 75 acres in 1918, trying a variety of crops such as native hay, barley, clover, oat hay and timothy. [36]

In the old Moran area, Joe Markham claimed a relinquishment in 1914 for 160 acres east of Oxbow Bend. By 1918, he had raised 65 acres of barley. On Willow Flats, George H. "Herb" Whiteman homesteaded in 1914, taking up residence in 1915. While working at Sheffield's camp or on the Jackson Lake Dam, he proved up his irregularly-shaped homestead. In 1915, Whiteman reported clearing 15 acres of sagebrush and cutting 45 tons of native grass. The next year he seeded 50 acres to timothy and winter wheat, harvesting more than 50 tons of hay. In 1917, the same acreage produced 62 tons of wild hay and wheat hay. [37]

North and east of Moran, there were a few scattered homesteads. At the outlet of Two Ocean Lake, William C. Thompson filed an entry in 1914. Four years later he planted 20 acres of barley and oats. On Pilgrim Creek, Samuel R. Wilson took up a homestead in 1916. Between 1917 and 1920, he cleared 21 acres, cultivating timothy, alfalfa, and barley one year, trying clover and millet another year. In 1920, he planted oats. Wilson irrigated his field with a three-quarter mile ditch that diverted water from Pilgrim Creek. [38]

After 1900, new advances in dry farming helped farmers cultivate arid lands. On the Great Plains, farmers reclaimed thousands of acres abandoned during the drought of the 1880s and 1890s. Although settlers in Jackson Hole preferred to irrigate their fields, dry farming provided a way to cultivate lands without irrigation. Based on available information, dry farming may have been more important in Jackson Hole than has been recognized.

Dry farming represented, from a farmer's view point, man's victory over nature—a way to grow crops with a minimum of water. Two practices were critical: using drought-resistant grains, and conserving moisture in the soil, particularly the subsoil. Wheats became the most important crop in the West, because some varieties are especially drought-resistant. Winter wheat, which is very drought-resistant, can also survive extremely cold temperatures. Winter wheat is planted in the fall, when rains help the seeds germinate. Spring wheat, which is grown primarily on the northern plains, can survive even harsher winters. Farmers plant it in the spring, and it matures in late summer. Spring wheat is the most suitable variety for Jackson Hole. To accomplish this, farmers leave land fallow on alternate years, which requires double the acreage. On the Great Plains, strip farming was employed to reduce wind erosion. Weed control was also important, as they compete with grain for the limited moisture. [39]

Settlers practiced dry farming in Jackson Hole, but to what extent is not known. A number of claimants failed to list ditches among their improvements, which would not have been omitted in final proof papers. This omission suggests that they dry farmed. As noted earlier, Holiday Menor listed no ditches. In 1912, Earle Harris, who homesteaded south of Menor, raised 30 acres of barley and wheat, which produced 18 tons of hay. Two clues suggest Harris dry farmed his land; barley and wheat are both drought-resistant crops and the 18-ton yield is consistent with dry farm production. On Antelope Flats and Mormon Row, a number of settlers such as John Kneedy, Talmadge Holland, John Nixon, Henry Gunther, and George Riniker raised crops, but did not list ditches as improvements. Talmadge Holland planted fall wheat (winter wheat) in 1918, but the severe winter killed the crop. John and T A. Moulton dry farmed grain until the state built ditches to their properties in the late 1920s. Clark Moulton, T. A. Moulton's son, dry farmed a 160-acre parcel for a number of years, until he sold out to the National Park Service in 1971. Nevertheless, irrigating lands remained the dominant practice in the valley. [40]

Rapid improvements in farm machinery also impacted agriculture in Jackson Hole. Horse-powered machinery cut the time required to plow, plant, and harvest—and partially solved the problem of labor shortages. The Wilson-Cheney party cut native grass by hand in the fall of 1889 to provide winter feed for their livestock. But these were temporary methods for most settlers. By 1900, ranchers and farmers cut hay with horse-drawn mowers. Settlers rented or borrowed machinery if they could not afford equipment. In the spring of 1914, residents of the Flat Creek area heard a mysterious chugging noise echoing through the valley. The noise came from the new steam-powered tractor owned by the J. P. Ranch Company. Farmers on Mormon Row used a steam-powered threshing machine to harvest oats and wheat, which provided a more efficient—although not particularly labor-saving—method of threshing grain. It took no fewer than half a dozen people to feed stalks of grain into the machine. The steam-powered tractor also failed to displace the horse as a means of power, because the former was expensive and not especially efficient on smaller farms. The gasoline-powered tractor, first developed by Henry Ford and Henry G. Ferguson during World War I, eventually displaced the horse on the farm. [41]

Several valley residents made limited use of other machinery. The windmill, a common innovation used to draw water from wells in the American West, apparently was not commonly adopted in Jackson Hole. No such windmills are known to exist on the park's few remaining farmsteads, and only one settler, Leslie Kafferlin, reported constructing one in his final proof papers. The Chambers family used one to generate electric power. At least one windmill is extant at a Spring Gulch ranch, south of today's park. William C. Thompson installed a hydraulic crane to pump water from the outlet of Two Ocean Lake. Bill Menor used a waterwheel to draw water from the Snake to his truck garden north of his cabin, but neither of these were common. [42]

As settlers preempted more land in the valley, conflicts with wildlife occurred. During especially severe winters, the elk raided the haystacks of the settlers. In response, homesteaders tried fences, guarded the haystacks themselves or with dogs, and fired guns to scare the elk—or, in some cases, shot them. None of these methods were completely successful. Elsewhere, frontiersmen solved the problem by exterminating the elk, but this was not an option in Jackson Hole. As noted elsewhere, many settlers earned a significant portion of their livelihood guiding wealthy dudes on elk hunts to secure trophy animals. Elk hides, antlers, heads, eyeteeth, meat, and even live elk became significant exports. Instead of killing off the elk, other solutions were adopted—such as controlled hunting, payments for damaged crops, and reserved lands. In contrast, ranchers had no reservations about eliminating the gray wolf in Jackson Hole. Stockmen's associations, such as the Fish Creek Wolf Association, were formed to exterminate wolves. [43] Rodents caused serious damage to crops. Fred Lovejoy produced a meager six tons of oat hay on his desert entry because gophers and squirrels destroyed the bulk of the crop. North of the Lovejoy ranch, Jim Budge experienced similar problems, when Uinta ground squirrels ruined most of a ten-acre crop in 1904. [44]

Severe weather, such as a prolonged drought or a 15-minute hailstorm, could destroy fields. Jim Chambers raised a prime crop of wheat on Poverty Flats (Mormon Row), only to have it wiped out by a sudden devastating hailstorm. He decided to raise hay and cattle in the future. Hail pummeled Geraldine Lucas's entire 20 acres of wheat in 1914; she raised timothy and alfalfa in succeeding years. Frost or freezing temperatures killed crops, and the hopes of some homesteaders. Talmadge Holland planted fall wheat at his farm on Antelope Flats in 1918, only to lose it to sub-zero temperatures. In 1916, Rufus Smith reported the loss of five acres of oats to frost and roaming cattle at his homestead on the Buffalo Fork. Along the Snake River above Pacific Creek, John R. Brown lost ten acres of oats to freezing temperatures in the same year. In a country that looked so green and appeared to have abundant water in snow-fed rivers and streams, drought seemed a remote possibility, yet settlers learned differently. William C. Thompson intended to plant wheat at his homestead straddling Two Ocean Creek in 1916, but the ground was too dry for a crop. At his farm north of Kelly, Charles Davis plowed 35 acres in 1917, but found the soil too dry for a crop. [45]

Even livestock could destroy crops, if homesteaders failed to install or maintain fences properly. J. R. Brown lost his first three-acre crop of oats to cattle in 1915. On Pacific Creek, Elmer Arthur planted 22 acres of clover in 1916; cattle ruined the entire crop before he could harvest it. In a few cases, homesteaders failed to harvest crops with no explanation. Roland Hunter raised a one-half-acre truck garden on his Buffalo Fork homestead around 1916, but harvested none of it. Joseph Chapline cultivated more than 14 acres of oats in 1920, yet simply let livestock grab it off. [46]

Some claimants were victimized by incredibly bad luck, or their own lack of initiative. In 1919, John G. Brown (not the John R. Brown mentioned above) homesteaded along the Buffalo Fork, but did not take up actual residence "as the snow was so deep that I could not get onto my claim any sooner." He managed to a small garden but harvested very little of it. [47] Charles Shinkle filed preemption papers on a 160-acre parcel north of Kelly in 1910. His final proof papers documented his setbacks:

1911 2 acres veg. cattle got it. 1912 3 acres 1/2 acre veg. 1 ton. 1913 No crop 1914 No crop too dry. 1915 3 acres cattle got it. 1916 3 acres 1 a.veg. 1/4 ton veg.

In 1922, William Smith filed an entry on 159 acres near the south entrance of the park. He plowed 15 acres the first season, then added five acres in 1923, planting 20 acres of oats, but "on account of drought and ground rodunts [sic] . . . crop wasn't worth harvesting." The next year he tried again, but experienced the same results. He filed final proof papers in 1928, confessing "I got discouraged with former results and did not again plant a crop. . . ." [48]

Many settlers relinquished their claims prior to securing a patent or title to the land. A significant number of people, forgotten in local history, tried homesteading in the valley, but gave up and left. Some sold their relinquishments, while others simply abandoned their claims. Norm Smith purchased the rights to his farm at Blacktail Butte from a man named Pembril in 1907. On Antelope Flats, several homesteaders acquired relinquishments after 1910. T. H. Baxter took over the abandoned property of Andy Bathgate, who returned to Sugar City, Idaho, in the fall of 1914. A man named Al Sellars relinquished his tract to John Kneedy in 1917. John Nixon took over the John Winkler claim in 1915. According to local tradition, Grant Shinkle homesteaded at the site of the present Teton Science School prior to Mickey Adams arrival in 1911. At Jenny Lake, both Moritz Locher and Ed Smith filed on entries that already had cabins on site, suggesting that others had given up the tracts. Tillman Holland reported a cabin on his entry when he took up residence in 1917. Joe LePage's 640-acre stockraising entry along the west bank of the Snake River had been claimed by Sinclair "Slim" Armstrong in 1922. He relinquished title to LePage in 1927. Joe Markham filed on an entry east of Oxbow Bend in 1914, after Steve Mahoney, the original claimant, was killed in an engine room accident at the Jackson Lake Dam. Dave Spalding homesteaded the JY, before relinquishing rights to Louis Joy around 1907. Even though no records explain why people abandoned their land, hard winters, isolation, lack of a "start" or capital, and the back-breaking work required to build cabins, clear fields, and dig ditches probably discouraged them. [49]

One major limitation, and a critical one for many homesteaders, was the lack of a "start," or sufficient money to devote all of their time to ranching and farming. Families had to be fed and clothed, while equipment, building materials, tools, planting seed, and breeding stock had to be purchased. Few possessed the cash to pay for these items. Furthermore, any kind of bad luck—such as an illness in the family, a barn destroyed by fire, a failed hay crop, or a dead draft horse—could prove disastrous. Thus, most settlers raised cash by working at other occupations or mortgaging their homesteads; sometimes they did both.

Floyd Wilson took up a homestead on the sagebrush flats near today's airport, intending to start a small ranch with a pair of horses and four cattle. Joe Jones started with four horses and four cows and leased acreage to Nephi Moulton for grazing. Neither had much of a start for cattle ranching. The Jump family homesteaded on Ditch Creek in the eastern side of the valley. Ethel Jump recalled that her family could not make a living on the homestead, so they hauled freight, guided dudes, trapped, hunted, and mined coal along Ditch Creek to sell locally. J. D. "Si" Ferrin farmed land on Flat Creek before becoming the largest rancher in Jackson Hole by 1920. In addition to being a farmer and rancher, Ferrin hauled freight, cut and hauled timber, and operated a sawmill. He also served as a state game warden for 14 years, earning a reputation as one of the most effective wardens in the valley. Many settlers became jacks-of-all-trades, taking advantage of any opportunity to earn hard cash. [50]

Besides farming land and grazing livestock, homesteaders used natural resources to earn a living. Trapping is generally associated with the mountain man's frontier, which ended around 1840. Yet itinerant trappers worked the valley during the years prior to settlement, as trapping and hunting continued to be an important economic enterprise in the West throughout the nineteenth century. Pierce Cunningham trapped for a living when he first came to the valley. Pioneer S. N. Leek also trapped to provide an income. After homesteading in the Flat Creek area in 1904, Jim Chambers spent the first winter trapping. He earned $200, enough to purchase a cow, chickens, and two small pigs. Coyotes, beaver, and members of the weasel family, such as pine marten, mink, and muskrat, were the primary targets of trappers. Andy Chambers trapped on the Snake River from 1918 to 1928. Many were not very scrupulous when it came to trapping illegally. Indeed, poaching added some excitement to the otherwise routine task of running traplines every few days. [51]

As noted earlier, the eyeteeth of elk were valuable commodities, used primarily as watch charms by members of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. Settlers removed the teeth from winter-killed elk and garnered as much $10 to $100 a pair, which was a considerable sum. The high prices eventually caused serious trouble. Rather than content themselves with winter-killed elk, a new kind of poacher—the tusker—began shooting elk for their eyeteeth alone. Tusking reached epidemic proportions before vigilantes acted to curb the problem. [52]

Cutting and hauling timber for fencing and construction materials provided another source of income for settlers. For example, D. C. Nowlin contracted with Jim Chambers to cut lodgepole fencing for the elk refuge. In 1914, Mickey Adams and Luther Hoagland hauled timber for Jim May, possibly for the construction of a church. Others invested in sawmills, such as S. N. Leek, J. D. Ferrin, and the Schofield brothers. Gold was panned from rivers and streams, if not in commercially viable amounts, in enough quantities to provide a little extra cash. Noble and Samuel Gregory earned enough from small-scale placer mining to pay for their annual stock of supplies. Settlers filed a large number of placer claims and some lode claims, hopeful of striking it rich. Early pioneers such as Uncle Jack Davis and Johnny Counts washed tons of river gravel and silt, but never found a profitable claim. One source estimated that Uncle Jack Davis washed 100 rocker boxes of dirt per day and retrieved about a penny's worth of gold for each box load. He did not get rich on a dollar a day. [53]

Many homesteaders worked for wages to live and provide capital for proving up their homesteads. John Rutherford testified that he left his homestead from June 1910 to April 1911 "to earn money to live on and to improve the land." He and his wife were absent from the land from Christmas Eve 1913 to April 1914; while the Rutherfords awaited the birth of their second child, and John Rutherford fed cattle to support his family. Herb Whiteman worked either for the Reclamation Service or Ben Sheffield "to earn money to pay bills to improve my entry." Whitemans neighbor, Charlie Christian, left his homestead from December 1919 to the end of April 1920 to work in the coal mines at Superior, Wyoming. [54] James Manges did not support himself at his Taggart Creek homestead, but worked as a carpenter at the Bar BC in 1913. S. N. Leek hired the Estes brothers to thrash grain at his South Park ranch in 1909. Providing their own team and working for two days, they earned $5. E. B. Ferrin hired out to saw wood for $1 per cord in 1915. [55]

|

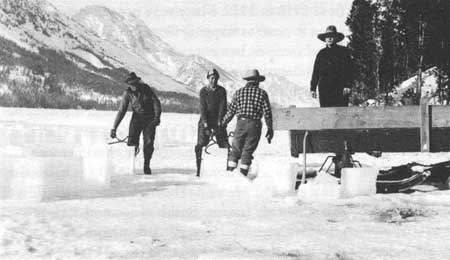

| Settlers cut blocks of ice in the winter; the ice would be stored in well-insulated ice houses to provide refrigeration throughout the summer. Grand Teton National Park |

The emergence of dude ranches after 1907 created jobs in the valley. At the Bar BC in the early 1920s, Struthers Burt and Horace Carncross hired "two cooks, a dishwasher, two waitresses, two cabin-girls, a housekeeper, two laundresses, a rastabout [sic], a carpenter, a rastabout's [sic] helper, two horse wranglers, a teamster, a foreman, two young dude wranglers, a truck driver and two guides, two camp horse-wranglers, and two camp cooks." Counting the owners and their wives, the ranch needed 29 people to care for 52 dudes. The same year he submitted his final proof papers, Charles Ilse worked at the Bar BC filling in for wrangler Lewis Fleming. Jimmy Manges worked for a number of dude ranches over his lifetime. In 1924, he returned from Leigh Canyon with a pack outfit from the JY, only to start work as caretaker for the Double Diamond Dude Ranch. Although he ranched in South Park, Frank Tanner worked as a wrangler at the JY, the Bar BC, and the Half Moon after 1918. A few worked for dude ranches so long that their names became as synonymous with the ranch as the owners. Frank Giles was a cowpuncher who became a wrangler at the Bar BC, and later the caretaker and foreman of Burt's Three Rivers Ranch. Frank Coffin homesteaded on the Buffalo Fork, but worked for Dad Turner at the Triangle X for most of his life until his death in 1951. Dude ranches provided employment not only for men, but for their wives and daughters. [56]

Others built facilities to cater to hunters. Stephen Leek became one of the first to guide eastern dudes in Jackson Hole, one of the most prominent being George Eastman. Prior to 1900, Leek constructed a hunting lodge at the north end of Leigh Lake; the establishment was known as Leek's "clubhouse." He later established Leek's Camp on the east side of Jackson Lake. Ben Sheffield was the largest early outfitter, establishing a lodge and headquarters at Moran. Leek and Sheffield devoted more time to the guide business than most settlers.

Since hunting season took place in the fall, farmers and ranchers reserved this period for guiding dudes. For example, Frank Price filed preemption papers on 160 acres on the north side of the Gros Ventre River in 1901. In 1906, he testified that he was absent for two months every year guiding "tourists." A remarkable number of Jackson Hole settlers were involved in the guide and outfitters business on a part-time basis. Roy Lozier, who homesteaded near Moran, guided hunters for almost 35 years and was considered one of the best in the valley. Abe Ward of Wilson not only ran a hotel, but worked as a tour guide for years; he guided George Eastman for nine seasons. John Cherry, one of the valley's first ranchers, guided dudes until he left the valley around 1917. He was so proficient at "spinning long yarns" that one of his dudes based a book on Cherry, titled The Life and Lies of John Cherry. Outfitters hired local help. In 1914, Rudy Harold guided a party of Los Angeles attorneys into the backcountry to hunt elk and bighorn sheep. Charlie Hedrick and J. P. "Pete" Nelson accompanied Harold as guides. The J. P Nelson photograph collection records the hunting expeditions of Moser and Trexler; some of the packers and guides included ranchers Frank Sebastian, Frank Petersen, and Guy Germann. The list of guides is long: George Ross, Cal Carrington, Louie Fleming, Milt Young, Jim Budge, James Manges, George "Herb" Whiteman, Jack Eynon, Joe Jones, Dick Winger, and the Wort family, to name a few. [57]

Freighters also assumed special importance in this remote mountain valley. J. D. "Si" Ferrin freighted supplies from Idaho over Teton Pass and throughout the valley. A number of homesteaders hauled freight over the Ashton-Moran freight road for the Reclamation Service and private individuals. [58] Contracts to carry mail were coveted, even though the hours were long and bad weather made the work miserable. The job could be dangerous, too. River fords, skittish horses, and avalanches in winter were hazards that went with the job. Until the 1930s, mail was delivered to Jackson Hole via the Oregon Short Line through Idaho, then by wagon, sled, or skis over rugged Teton Pass. Jack Eynon, who migrated to Jackson Hole from Victor, Idaho, packed mail over the pass on snowshoes for several winters. Early pioneers such as rancher Noble Gregory and Mart Henrie also carried mail in the valley. Henrie hauled mail from Jackson to Moran from 1902 to 1910, while proving up his homestead in the Kelly area. During hard economic times, mail contracts could make a real difference. Andy Chambers had the Jackson-Moran mail contract from 1932 to 1940. At the same time, he raised hay and cattle on his Mormon Row homestead. [59] Operating post offices provided another source of income, and it was common for women to be the designated postmasters. Of 13 postmasters at Elk between 1897 and 1968, ten were women. All were wives of local ranchers, or were homesteaders themselves, such as Eva Topping. [60]

Mail contracts and postal appointments were two of the numerous jobs classified "government" work. A common perception exists that Jackson Hole settlers were rugged individualists who tamed the land with sheer grit and initiative. Government was an obstacle and hindrance that people could do fine without—a common perception in the West even today. In truth, many Jackson Hole pioneers worked for the county, state, or federal government either through contracts or direct employment. The arrival of the Forest Service, National Park Service, Reclamation Service, Biological Survey, and the State Game and Fish Department marked a new age after 1900. These bureaus regulated, and often restricted, resource uses so common on the nineteenth-century frontier. As the State of Wyoming established laws regulating hunting, fishing, and trapping, local citizens were hired as game wardens, both part-time and full-time. Albert Nelson and D. C. Nowlin were the first game wardens in the valley. Ranchers J. D. Ferrin and Roy McBride also worked as game wardens. Road construction and maintenance provided a very important source of cash in the valley. County, state, and federal governments allocated funds for a succession of road improvements in the years after 1900. For example, Luther Hoagland hired out himself and a team of horses to work on road improvements in Yellowstone in 1914. The construction of the dams at Jackson Lake in 1907 and 1910 generated an economic boom in the valley. Many homesteaders worked at the dam for wages, among them P C. Hansen, Joe Pfeifer, and Herb Whiteman. These construction projects brought new settlers to Jackson Hole. Harold Hammond first came to the valley in 1910 to work for the Reclamation Service as a wrangler. In 1913, he filed entry papers on the White Grass Ranch.

The creation of the Teton Forest Reserve in 1897 brought a new frontier character to Jackson Hole. R. E. Miller, one of the valley's first homesteaders, was the supervisor from 1902 to 1918, earning a salary of $2,000 per year. Unable to make a living as Jackson's first dentist, C. D. Horel received an appointment as a forest ranger. His wife, May Horel, homesteaded along Cottonwood Creek near Moose. Albert Gunther and his brother, Henry, had been raised by the Infangers on Flat Creek. In his early 20s, Albert Gunther homesteaded on Mormon Row in 1908. When times got tough, he worked for the Forest Service at Kelly for 13 years. [61]

Rather than try to earn a living year-round and endure the long winters, a few settlers left the valley each fall and returned after the snowmelt. Andrew Newbold returned to his "Lone Tree" Ranch in April 1914 after leaving for the winter. William Ireton, who homesteaded on Antelope Flats, spent the winter of 1917-1918 in Chicago. May Horel returned to her ranch on Cottonwood Creek in 1917 after wintering in Oregon with her three children. Ellen Dornan left her small tract in 1922, wintering in Pennsylvania. The Sensenbachs, who homesteaded the Highlands Ranch, also spent the winter of 1927-1928 in Pennsylvania. H. C. Ericcson, an attorney from Kansas, was a "suitcase" rancher and land speculator, who spent each winter in Kansas between 1923 and 1931. One entrant, Anton Grosser, left his homestead for more than a year in 1914 for unknown reasons. He failed to acknowledge this absence in his final proof papers, submitted in 1916, a clear instance of false testimony to secure a patent. [62]

Jackson Hole settlers remained mobile after moving to the valley. Mose Giltner owned a ranch just south of Spring Gulch in 1892. Six years later, he purchased the "Slough Grass" Nelson property on Flat Creek, even though it had serious drainage problems. Nelson moved to the Zenith area near the confluence of the Snake and Gros Ventre Rivers. Joe Heniger lived on three ranches or homesteads over his lifetime. Heniger came to Jackson Hole in 1900 and purchased the John Emery place in the Flat Creek area. Around 1909, he sold this property and filed preemption papers on 160 acres in the north end of the valley, not far from the Wolff ranch. Heniger then sold this property and moved to Utah around 1920, only to return later and purchase the Thomas Murphy place on Mormon Row. Si Ferrin farmed on Flat Creek in 1900, but sold this property and located a homestead south of the Buffalo Fork in 1908. Pierce Cunningham, tired of ranching, sold his 320-acre property to J. P. Nelson for $6,000 in 1909. Other sources claim the Cunninghams traded the ranch for the Jackson Hotel. Five years later, the Nelsons sold the ranch to Maggie Cunningham for $6,500. The Cunninghams sold the hotel to Jack Eynon, who relocated in the valley from Victor, Idaho. Occasionally, people staked out a homestead only to find it unsuitable for a farm or ranch. Tom Jump located a good tract of land along the Snake River near Moose after 1900. The first winter he found the snowdrifts to be impassible and abandoned the property for a place on Ditch Creek. Ranchers and farmers leased their properties on occasion, although the records do not indicate if this was a common practice. In 1917, for example, Don Miller leased the Carpenter, Ireton, and Geck homesteads on Antelope Flats. Miller later purchased the Adams ranch on Ditch Creek and leased it to the Kent family. [63]

Like most frontiers, whether the miners' or the farmers', the people who made the most money were merchants or professionals who supplied goods and services. Some homesteaders left their land after a number of years, or worked at an occupation from their farms or ranches. Albert Nelson worked as a taxidermist for about six months of the year at his Savage Ranch at Kelly. His neighbor, William J. Kelly, established a cattle ranch, but made his living as a cattle broker, buying and selling cattle for export. Frank Lasho, homesteading along the Snake River near today's airport, listed his trade as "smithy." Mart Henrie homesteaded in the Kelly area from 1899 to 1910, when he moved to Jackson and opened a boot and harness shop. Norm and Alice Bladon homesteaded west of Menor's Ferry in 1914, while living and working in Jackson to earn money to prove up their land. Bladon was a taxidermist. Joe Jones left his homestead south of Blacktail Butte and moved to Jackson in 1912. He established the Elk Store, a pool hall and tobacco parlor. Jones later started a grocery, which he ran for ten years. Dick Winger migrated to Jackson Hole in 1912, filing papers on land he had never seen. Winger had been in the valley only a short time when he purchased the Jackson's Hole Courier in 1913, which he published and edited for the next six years. Winger later worked as a realtor and contractor on road projects. William Grant eventually opened a grocery on his homestead along the present Moose-Wilson Road, which also became the first Moose Post Office in 1923. [64]

Many of Jackson Hole's settlers left the valley to retire. They left for a number of reasons, such as poor health or to escape the bone-chilling winters. Jackson Hole's first permanent settlers, John Holland and John Carnes, were gone by 1900. Holland left for Oregon, while Carnes located much closer at Ft. Hall, Idaho. Idaho became a popular retirement location because the cost of living was cheaper and the climate milder than Jackson Hole, yet it was close to friends and relatives. Jack Shive retired to Idaho Falls after selling out in 1919. [65] Pierce Cunningham moved to Victor, Idaho, after selling out to the Snake River Land Company in 1928. In 1918, James I. May retired to Honeyville, Utah, another popular location. James and Lydia Uhl moved to Utah in 1918, selling their 240-acre ranch to the Cunninghams. In 1917, John Cherry and "Pap" Nickell sold their acreage at Warms Springs to A. J. Whidden and Dr. W. R. Gillespie. Having nothing to do but rest and fish, Cherry retired to Salmon, Idaho, returning to Jackson Hole in the summers. Nickell retired in southern Missouri. Billy Bierer sold his homestead on the Gros Ventre to Guil Huff and moved to his daughter's home in Pennsylvania, where he died in 1923. [66]

California became perhaps the most popular retirement location, obviously because of its desirable climate. Tired of contending with the vagaries of the Snake River made worse by the regulated water flow from the Jackson Lake Dam, as well as the extreme weather conditions in the valley, Bill Menor sold his ferry and homestead to Maud Noble in 1918 and retired to San Diego, California. Holiday Menor sold out in 1928 and joined his brother. Harry Smith had homesteaded only a very short time along the Gros Ventre before selling his ranch to P. C. Hansen. He moved to San Bernadino, California, and became a citrus grower. Others who moved to California were Jude Allen, Karl Kent, Doc Steele, and James Uhl, who left Utah after his wife's death. So many Jackson Hole residents retired to California that they were able to hold reunions, such as a picnic in 1939 attended by nearly 70 former residents. [67]

Poor health forced some to leave the valley. Burdened with a bad heart, John G. Brown sold his homestead on the Buffalo Fork and relocated to Oregon in 1918. Mickey Adams moved to Grass Valley, California, because of a heart condition. The Uhls moved because of Lydia Uhl's poor health. Fred Cunningham left Jackson Hole in 1920, seriously ill with cancer. Despondent over poor health, he committed suicide later that year. [68]

Many of Jackson Hole's pioneers retired during the economically depressed years following World War I. The armistice of November 11, 1918, ended the war, as well as the high demand—and high prices—for American farm products. Prices plummeted in 1919, beginning two decades of depression in American agriculture. In addition, a severe drought parched much of the American West in 1919, delivering another blow to farmers and ranchers. In Jackson Hole, settlers watched helplessly as crops shriveled and cured under the relentless sun. Settler after settler testified to the completeness of the disaster in their final proof papers. On Antelope Flats, Talmadge Holland planted oats and barley but, on account of drought, produced no crops. Neighbor Ray C. Kent, who homesteaded the Lost Creek Ranch, reported "no harvest on account of drouth." West of Blacktail Butte, Sam Smith wrote "dry weather, no farm." John Kneedy, east of the Snake River, lost his crop. West of Menor's Ferry, the recently widowed Alice Bladon produced one ton of potatoes, "but no oats hay, It was too dry." Horace Eynon did not grow a crop on his Spread Creek homestead as it was "too dry." The drought lasted 100 days before an afternoon rainshower settled dust in the valley. However, as the Courier reported, it was too late for most crops. [69]

One bad year does not spell doom for farmers and ranchers. But bad years tend to accumulate and carry over into succeeding years. Frank Bramen lost his crop on his Pacific Creek homestead in 1919, but planted no crop the next year because of the loss of his workhorses. Horace Eynon did not cultivate any crop in 1920 because of a "lack of feed for his stock." The 1919 drought had ruined his crop the previous year. [70] The Jackson's Hole Courier listed 34 foreclosures on farms and ranches in Teton County between 1923 and 1932 and a handful of tax sales. It began with the foreclosure of the Tillman and Mattie Holland place near Kelly in 1923. The Hollands were unable to pay off $500 borrowed from Ellen Hanshaw in 1920. In addition, they owed $153.32 in interest and $75 in attorney's fees. As a result, Holland, his wife, and six children lost their land. Most ranchers and farmers scrabbled to make ends meet. Judging from the county records, most got by, for relatively few mortgages were taken out in the 1920s. [71] Still, as the years passed, the lists of property owners owing back taxes increased until they took up a full page in 1926. The roll included some of Teton County's most prominent citizens.

Dude rancher Struthers Burt believed the valley's economic problems originated with the unfortunate propensity of the American to try "to suit the country to himself," rather than "suit himself to the country." According to Burt, cattle ranching was the only suitable agricultural use for the valley. The farmers who came to Jackson Hole preempted grazing range and, in Burt's opinion, were unable to make a living on the land. In his The Diary of a Dude Wrangler, published in 1924, Burt wrote "the first farmers came into my valley about ten years ago and today they are broken and ruined men." [72]

A series of executive orders in 1926 and 1927 withdrew public lands in Jackson Hole from settlement, effectively closing the homesteader's frontier. In 1928, the Snake River Land Company began purchasing most of the private lands in Jackson Hole north of the Gros Ventre River. The company, financed by John D. Rockefeller Jr., purchased more than 32,000 acres over a six-year period. The land, which would eventually become part of Grand Teton National Park, included many of the former farms and ranches of Jackson Hole's pioneers.

Notes

1. Census of the United States, 1900, Jackson Precinct.

2. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 335-337; and Frederick Merk, History of the Western Movement, (New York: Alfred A Knopf, 1978), pp. 330-346.

3. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 599-606.

5. Merk, History of West, p. 474; and Driggs, History of Teton Valley, pp. 151-156.

6. Interview with Jim Budge by Jo Anne Byrd, #5, "Last of Old West Series."

7. Frances Judge, "Second Life," Atlantic Monthly (July, 1954):58.

8. Interview with Ellen Dornan, #10.

9. Homestead Patents, Homestead Cert. 1006, Lander, James Budge, 1904; and Jackson's Hole Courier, May 7, 1914.

10. J. E. Stimson Collection, "Interior of R. Miller's Home, Jackson Hole, Wyoming," D102, Photograph, Wyoming State Archives; Owen, T41N, R116W, 6th PM.; Harold and Josephine Fabian Collection, Grand Teton National Park; Jackson's Hole Courier, September 3, 1914; and Jackson Hole Guide, May 24, 1974.

11. Brown, Souvenir History of Jackson Hole, p. 12; and Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, p. 30. Accounts are contradictory regarding the first sawmill in Jackson Hole and how it arrived here. Leek was the first resident to operate a sawmill in the valley.

12. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 28, 1909, reprinted in Jackson's Hole Courier, January 29, 1948; Census of the United States, 1900, Jackson Precinct; and Struthers Burt, Diary, pp. 131-132.

13. Struthers Burt, Diary, p. 13; and Jackson Hole Guide, October 14, 1965.

14. Homestead Patents: Homestead Cert. 1049, Evanston, Albert Nelson, 1904; and Homestead Cert. 526, Lander, William Kissenger, 1904.

15. Homestead Patents: Homestead Cert. 334, Lander, James May, 1901; Homestead Cert. 1006, Evanston, James Budge, 1904; 496735, Jacob Johnson, 1914; 534689, T. A. Moulton, 1915; 542215, Andrew Chambers, 1916; and 705531, John W. Woodward, 1918; and Jackson's Hole Courier, May 8, 1916.

16. Homestead Patents: 486627, James Williams, 1915; 517650, Ransom Adams, 1915; and 587696, J. R. Smith, 1916.

17. Homestead Patents: 639818, James Manges, 1917; 615962, Charles Ilse, 1917; 737603, William Grant, 1919; 1037175, Shadwick Hobbs, 1929; and 1038450, Lewis Fleming, 1929. I have never found a satisfactory explanation as to why the Hobbs cabin is referred to as "starvation" cabin, an intriguing description.

18. Homestead Patents: Homestead Cert. 1181, Evanston, J. P Cunningham, 1904; Homestead Cert. 1152, Evanston, James Uhl, 1904; 323588, J. D. Ferrin, 1912; 522255, Otto Kusche, 1915, and 601314, Gottfried Feuz, 1917.

19. Jackson Hole Guide, May 20, 1976; and Homestead Patent 1037175, Hobbs, 1929.

20. Jackson's Hole Courier, July 16, 1931, and March 25, 1943; Jackson Hole Guide, December 2, 1965; and Nellie Van DerVeer, "Teton County-Pioneer Stories," WPA Subject File 1328, Wyoming State Archives.

21. M. H. Kneedy operated a flour mill at Kelly for a time.

22. Jackson's Hole Courier, September 3, 1914, and August 17, 1916; Homestead Patents: 522255, Kusche, 1915; and 531858, Anton Grosser, 1916; interview with Parthenia Stinnett by Jo Anne Byrd, "Last of the Old West Series;" and Jackson Hole Guide, April 7, 1966.

23. Homestead Patents: 707967, Steingraber, 1918; 708783, Norman Smith, 1918; 516805, John Rutherford, 1910; 504029, James H. May, 1908; and 733997, Roy Lover, 1915.

24. Interview with Clark Moulton by Jo Anne Byrd, #27, "Last of the Old West Series;" and Homestead Patents: Desert Land Entry 152, Lander, James I. May, 1901; and Desert Land Entry 768, Evanston, James Budge, 1901.

25. Homestead Patents: Homestead Cert. 529, Lander, Fred Lovejoy, 1904; Desert Land Entry 233, Lander, Lovejoy, 1903; and 511897, Mary Lovejoy, 1913.

26. Homestead Patents: Homestead Cert. 469, Lander, Nels Hoagland, 1903; Desert Land Entry 169, Lander, Hoagland, 1901; 338393, William J. Kelly, 1913; 831413, Kelly, 1914; and 903929, Sophie S. Kelly, 1922.

27. Homestead Patents: 486627, Williams, 1915; and 517650, Adams, 1915.

28. Homestead Patents: Johnson, 1914; 542215, A. Chambers, 1916; and 705531, J. Woodward, 1918.

29. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 15, 1915; Orrin and Lorraine J. Bonney, Bonney's Guide to Grand Teton National Park and Jackson's Hole (Houston, TX: by author, 1961, 1972), p. 131; and Homestead Patents: 485599, Joseph Pfeifer, 1914; and 598873, Henry Gunther, 1917.

30. Homestead Patents: Desert Land Entry 767, Evanston, Richard H. Meyers, 1906; and 732049, Roy Nipper, 1919.

31. Homestead Patent 685989, H. H. Menor, 1918.

32. Homestead Patent 639818, James H. Manges, 1917; and Office of the Teton County Clerk and Recorder, Misc. Records Book 1, p. 280, James Manges to C. A. Goss, Agreement for Deed, April 1, 1926; and Deed Record Book 4, p. 114, James Manges to C. A. Goss, Warranty Deed, August 7, 1929.

33. Homestead Patents 615962, Ilse, 1917; and 737603.

34. Homestead Patents: 959955, Heirs of M. Locher, 1924; and 981691, Ed K. Smith, 1926; and "Hearing on S. Res. 226," 1933, p. 271.

35. Homestead Patents: 486340, Charles Hedrick, 1915; 486342, John Fee Jr., 1915; 486346, Orin Seaton, 1913; 516802, Rudolph Harold, 1915; and 899898, William Jump, 1922.

36. Homestead Patents: 396790, Walter J. Germann, 1913, and 769868, John Smejkal, 1918.

37. Homestead Patents: 707968, George H. Whiteman 1918; and 796556, Joe Markham, 1918.

38. Homestead Patent 645202, William C. Thompson.

39. Merk, History of West, pp. 484-494; and Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 359-365.

40. Interview with Clark Moulton, #27; and Homestead Patents: 519467, John Moulton, 1915; 534689, T. A. Moulton, 1915; 563869, George H. Riniker, 1916; 598873, Henry Gunther, 1917; 674905, John Nixon, 1918; 730043, Earle W. Harris, 1918; 802555, John L. Kneedy, 1920; and 813101, Talmadge S. Holland, 1918.

41. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 30, 1914; Merk, History of West, pp. 591-592; photograph of threshing machine, Book 5, p. 24, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum, and Jackson Hole News, August 30, 1973.

42. Homestead Patents: 645202, W. C. Thompson, 1917; and 517646, Leslie Kafferlin, 1915.

43. Jackson's Hole Courier, July 19, 1914.

44. Homestead Patents: Desert Land Entry 233, Lander, F. Lovejoy, 1903; and Desert Land Entry 768, Evanston, James Budge, 1905.

45. Bertha Chambers Gillette, Homesteading with the Elk: A Story of Frontier Life in Jackson Hole, Wyoming (Idaho Falls, ID: Mer-Jons Pub. Co., 1967), pp. 138-141; Homestead Patents: 868566, Geraldine Lucas, 1921; 813101, Talmadge S. Holland, 1918; 645202, W.C. Thompson, 1917; and 710289, Charles Davis, 1918.

46. Homestead Patents: 804575, John R. Brown, 1920; 587701, Elmer Arthur, 1916; 701008, Roland P Hunter, 1918; and 817079, Joseph Chapline, 1920.

47. Homestead Patent 804575, J. R. Brown, 1920.

48. Homestead Patents: 715943, Charles Shinkle, 1918; and 995670, William Smith, 1925.

49. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 654-655; Jackson Hole Guide, October 12, 1972; interview with Ellen Dornan by Jo Anne Byrd, #10, "Last of Old West Series; U.S. Geological Survey, Grand Teton Quadrangle, surveyed in 1899; Jackson's Hole Courier, April 16, 1914, July 12, 1917, December 5, 1919, October 12, 1922; A. N. Davis, G. L. O. Commissioner, Homestead Entry Ledger, p. 98, courtesy of Noble Gregory, Jr.; and Homestead Patents: 674905, Nixon, 1918; 606336, T H. Baxter, 1916; 802555, J. L. Kneedy, 1920; 796556, Markham, 1918; 788386, Tillman Holland, 1920; 959955, Heirs of M. Locher, 1924; and 981691, Ed K. Smith, 1926.

50. Homestead Patents: 243672, Floyd Wilson, 1911; and 323593, Jones, 1913; interview with Ethel Jump, February 19, 1966, transcript, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Jackson Hole Guide, December 2, 1965.

51. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 19, 1934, March 25, 1943, and November 8, 1945; Jackson Hole Guide, February 8, 1968; and Gillette, Homesteading with Elk, p. 15.

52. Gillette, Homesteading with Elk, pp. 4 and 156; Hayden, Trapper to Tourist, p. 53; and Jackson Hole Guide, October 6, 1955.

53. Gillette, Homesteading with Elk, pp. 4-15; Jackson's Hole Courier, April 16, 1914; and Jackson Hole Guide, October 6, 1955.

54. Homestead Patents: 516805, John Rutherford, 1915; 707968, Whiteman, 1918; and 804576, Charles Christian, 1920.

55. Jackson Hole Guide, July 2, 1964 (this article contained a number of errors); S. N. Leek Collection, 3138, Box 3, Ledger Book; and Jackson's Hole Courier, February 4, 1915.

56. Struthers Burt, Diary, p. 181; Jackson's Hole Courier, May 10, 1917, September 18, 1924, January 24, 1952, and November 15, 1951; and interview with Bill Tanner by Jo Anne Byrd, #39, "Last of Old West Series."