|

Grand Teton

A Place Called Jackson Hole A Historic Resource Study of Grand Teton National Park |

|

CHAPTER 10:

Cattle Ranchers

If this ground is as valuable as they say it is, there's no way that I can see that our kids are going to stay here and keep ranching. I hope they are not that dumb. Us old fellows . . . we'll probably ride it out, but the kids aren't going to do it. I mean they're going to put her in the bank and go on down the road.

—Earl Hardeman Jackson Hole Guide, July 10, 1986

|

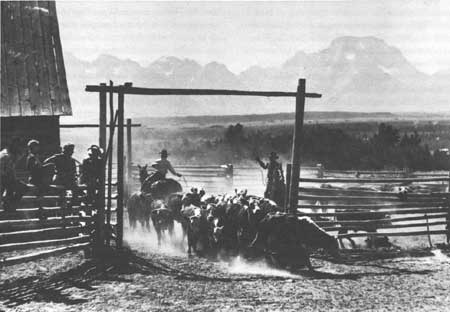

| Cattle ranching shaped the character of the western states. From the late nineteenth century through the early twentieth century, ranching was the primary occupation of most Jackson Hole residents. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

The open range cattle industry brought other frontiersmen to the American West, the rancher and cowboy. Like those before them—trapper, explorer, miner, soldier—the rancher played an important role in the development of the West, even though the years of the open range cattle industry were short-lived, lasting only from 1866 to 1887. This frontier gave birth to the cowboy, the most popular and enduring of this nation's folk heroes. It also pioneered modern ranching, which dominates the economies of several western states today.

Four important elements contributed to the development of ranching. First, native grasses carpeted the Great Plains, providing grazing for livestock. The establishment of cattle ranches represented an adaptation of farmer and hunter-woodsman to the Great Plains environment. In turn, ranchers manipulated the environment by introducing cattle. Second, the removal of native peoples and the extermination of native animals, such as the buffalo, created a vacuum that cattle and cowpunchers filled rapidly. Third, the Spanish had introduced cattle in northern Mexico and Texas in the eighteenth century, which provided a livestock source. In the Nueces River area, Mexican ranchers learned to raise cattle on the plains, developing the open-range cattle industry. Anglo-Americans learned the techniques of this system from the Mexicans. By 1865, an estimated 5,000,000 cattle roamed the Texas plains, providing an ample supply. Fourth, the Civil War depleted cattle supplies in the Mississippi Valley, creating a need for cattle in eastern markets.

Beginning in 1865, entrepreneurs collected unbranded cattle in Texas and, in the spring of 1866, outfits of six to 12 cowboys began driving herds of 1,000 to 2,500 cattle to a railhead at Sedalia, Missouri. An estimated 260,000 cattle were gathered in 1866 alone. Few reached Sedalia for a number of reasons, but the legendary long drives had been launched. Cattle trails developed from Texas to rail towns in Kansas, such as Abilene, Ellsworth, and Dodge City. If prices were good, the herds were sold for fattening on the Midwest corn belt. If prices were low, drovers moved the cattle to Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas. [1]

By 1869, the cattle industry had entered a "golden era." From the great drives, cattlemen settled the northern plains and stocked the range. Ranchers built up empires, preempting choice lands having water, and grazed their herds on the public domain free. The first to graze the range established first rights; it was an extralegal custom, but one that ranchers enforced with guns. Cattle "barons" emerged, such as John Wesley Iliff of Colorado and Conrad Kohrs of Montana. The King Ranch in Texas consisted of more than 1,000,000 acres. To regulate ownership of drifting cattle, control rustlers, eradicate predators such as wolves, and improve breeds of cattle, ranchers formed livestock associations. These groups controlled roundups in given localities where owners separated their cattle. At the spring roundup, they branded calves, castrated male calves (steers), and branded mavericks. Ranchers held fall roundups to gather steers for market.

Several characteristics typified the open range cattle industry in the 1870s and 1880s. To control the range, ranchers took advantage of homestead laws, especially the Desert Land Act of 1877 and the Timber Culture Act of 1873, to preempt prime acreage on the plains. Fraud typified many of the entries. One source estimated that up to 95 percent of desert land entries were fraudulent claims made for corporations. [2] Rather than bothering to secure legal title to land, cattle barons began fencing public land grazed by their herds. Though they had no legal right to do this, no one attacked the practice until the 1880s. To improve the rangy Texas longhorn, ranchers imported English Herefords and Scottish Black Angus. Cattlemen had to adapt to the northern plains where the winters were much worse than on the southern plains. In Texas, a cow could produce 12 offspring over a lifetime; on the northern plains, a cow could only be expected to deliver six calves. By the 1880s, some ranchers were cultivating hay for winter feed and putting up winter shelters to protect their cattle. [3]

The cattle industry boomed as wealthy investors from the East and Great Britain poured capital into giant cattle ranches in the West. By 1880, profits and propaganda ignited a predictable rush as hundreds of green young men from eastern farms and cities overran the West to join the new western aristocracy, the cattlemen. In 1860, no cattle were reported in the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado; by 1880, the census listed a figure of 1,881,769 cattle in these states and territories. [4]

In Wyoming, traders had brought cattle to the southeastern part of the state by the 1850s, while Mormons may have introduced cattle in the southwestern part of the state during the same period. John Wesley Iliff, a Colorado rancher, introduced the first large herd into the Cheyenne area in 1868. In 1870, the Wyoming Territorial tax assessment rolls listed 8,143 cattle in Wyoming; in 1880, the U.S. census listed 521,213 cattle in Wyoming Territory. By 1885, there were an estimated 1,500,000 cattle in Wyoming. The Scottish-owned-and-financed Swan Land and Cattle Company was the largest "outfit" in Wyoming, owning 123,460 head in 1885. The majority of cattle in Wyoming were Texas cattle. Cattle similar to longhorns came from the Midwest, Oregon, Washington, and Utah. A. H. Swan and J. M. Carey introduced the first Hereford cattle in 1878, and members of the Wyoming Hereford Association imported 400 head of Hereford bulls and cows in 1883.

In the 1880s, cattlemen dominated the politics and economy of the Wyoming Territory. Cattle accounted for more than three-quarters of the territory's wealth, while the Wyoming Stock Growers Association emerged as the single most powerful organization, wielding tremendous political influence. "Cattle Kings," along with merchants, comprised the social elite in the territorial capital in Cheyenne. [5]

The promise of tremendous profits led to an overstocked range. Experienced ranchers watched in alarm as prime grasslands shrunk and deteriorated under the onslaught of thousands of cattle. Furthermore, the increased supply of beef caused prices to decline. Adverse weather busted the industry, beginning with a hard winter in 1885-1886. Drought gripped the land during the summer of 1886. Concerned about the weakened condition of their herds, some ranchers dumped their cattle; as a result, the price of a steer plummeted from $30 per head in 1885 to no more than $10 each in 1886. Those who sold and took crippling losses may have been lucky.

The winter of 1886-1887 was one of the worst in recorded history and ended the days of free-ranging cattle on the Great Plains. The spring thaw revealed the extent of the disaster; cowboys spent a lifetime trying to forget the horror of thousands of dead cattle, piled up in ravines and along fence lines. Accurate numbers are difficult to determine, but it is estimated that winter losses totaled 40 to 50 percent of the cattle on the plains. [6]

Ranchers in Wyoming suffered less, as losses were believed to be no more than 15 percent of the herds. But this figure is deceptive; the assessed value of cattle in the territory dropped 30 percent, surviving cattle were in poor shape, and the year's calf numbers were small. Low prices continued as ranchers dumped cattle on the market. Bankruptcy became the only solution for many, sparing neither small ranchers nor cattle barons. When the Swan Land and Cattle Company went bankrupt in May 1887, shock waves emanated through the industry. [7]

Other developments limited the future of the open range cattle industry. In the 1870s, farmers began settling the plains, preempting grazing range and water used by ranchers. Then, in the 1880s, the wool market boomed and sheep were introduced on the range, causing serious competition for grass and subsequent range wars between sheepherders and cattle men. The collapse of open-range cattle grazing pointed out the fundamental inefficiency of the system; free-ranging cattle were easy prey for rustlers and predators such as wolves, while overgrazing proved wasteful and depleted the overall quality of rangelands. [8]

The open-range days were nearing their end when the first cattle were reported in Jackson Hole. As cattle ranged throughout the West, ranchers introduced herds adjacent to Jackson Hole, primarily in the Green River Basin and southeast Idaho. By 1880, there were approximately 30,000 cattle in southeast Idaho, and perhaps as many as 50,000 in the Green River Basin. [9] In the company of a posse in pursuit of horse thieves, William Simpson entered the valley in 1883 and reported the presence of 100 legally-owned cattle. Most references speculate that the cattle belonged to John Holland, John Carnes, and Mike Detweiler. Since Carnes and Holland came from the Green River country, the cattle may have been driven into the valley over the divide separating the Green and Gros Ventre Rivers. However, this conflicts with most accounts that cite 1884 as the date of Holland and Carnes arrival. The cattle may have been trailed into the valley to graze for the season. [10]

Jackson Hole's environment prohibited the year-round grazing of cattle on range lands as practiced on the Great Plains. After the disaster of 1887, cattlemen adopted mountain valley ranching, called range ranching on the Great Plains. Rather than let cattle range freely in winter, ranchers cultivated hay and fed their herds during the winter months. Cattle were released on the open range during the summer and autumn only. Winter shelters were also built to protect the animals from the worst storms. Thus, the cowboy rapidly became an agricultural laborer, cutting and stacking hay and digging post-holes for fences. [11]

Long winters, with 30 to 40 inches of snow covering the ground, and limited range made this area unattractive to large companies or cattle kings. Small ranches developed in the valley during the 1890s; the cattle herds were typically small, limited by the amount of winter feed cultivated. They were often indistinguishable from a farm. Some settlers began with such small herds that they raised hay or grain to sell on the local market, and thus should be classified as farms rather than ranches. Others switched from one to the other as circumstances dictated. For example, Jim Chambers raised cattle and hay after a hailstorm flattened 40 acres of wheat on his Poverty Flats farm. Lacking water, Andy Chambers dry farmed his land on Mormon Row, raising grains such as oats and wheat until 1927, when he constructed an irrigation system and switched to raising cattle and hay. [12]

Cattle ranching became the economic mainstay of Jackson Hole. Virtually all homesteaders prior to 1900 started cattle ranches. Pierce Cunningham, Emile Wolff, James Uhl, Jim Budge, Jim May, Frank Sebastian, Frank McBride, and Fred Lovejoy were ranchers in today's park prior to 1900. [13] Four factors circumscribed the size of the ranches. First, the availability of winter feed dictated the number of cattle kept through the winter. In turn, the cultivable acreage of the home ranch determined the tonnage of hay produced each year. For example, according to the tax rolls of Uinta County, Pierce Cunningham owned 27 cattle in 1899. Ranchers planned to feed their cattle for about six months per year. Each cow consumed an average of 20 pounds of hay per day, or 4,000 pounds per season. If we assume that Cunningham fed his cattle for 180 days, he would have needed 54 tons of hay for his herd. In addition, hay would be needed for saddle and draft horses, which required about 5,000 pounds of hay per season. In the final proof papers for both his desert and homestead entries, Cunningham testified that he cultivated hay on 100 acres at his homestead, plus 75 tons on his desert entry. The production of hay can vary greatly in Jackson Hole, depending on soils, weather, and irrigation. If we assume that Cunningham produced an average of two tons per acre on 100 acres, he would have had 275 tons of hay available each year. In 1900, he should have had a large surplus of hay. According to his final proof papers, Cunningham raised 100 cattle and eight horses in 1897, which would have required 220 tons for the winter, providing a small surplus of hay. [14]

Federal homestead laws—which failed to allow sufficient acreage for a cattle ranch in the West also determined the size of ranches. In 1878, John Wesley Powell of the U.S. Geological Survey issued his famous report which, among other things, recommended that homesteaders be allowed to preempt a minimum of 2,560 acres for stock-raising purposes. In Jackson Hole, early ranchers tried to raise cattle on a 160-acre claim under the Homestead Act of 1862, and an additional 160 acres allowed under the amended Desert Land Act of 1891. Some tried to ranch a 160-acre parcel, which was too small to be successful. Congress passed the Stock-Raising Act in 1916, which allowed settlers to preempt up to 640 acres of land suitable only for grazing. Theoretically, cultivable lands were excluded from this law.

Third, as homesteading accelerated in the valley after 1910, newcomers claimed more accessible grazing lands in the valley, forcing ranchers to drive their cattle to more remote range. This reduced the grazing acreage available and drove up operating costs. [15] Finally, after 1900, the Forest Service began to restrict grazing on public lands through a permit system. Like their predecessors on the Great Plains, Jackson Hole ranchers grazed livestock on the public domain, free and unchecked. The creation of the Yellowstone Timber Preserve in 1891 through the Forest Reserve Act served notice that conservation was a function of government. The service intended to prevent rangeland damage by restricting grazing to specific areas and limiting livestock numbers.

Establishing the grazing permit system became one of the most difficult and persistent problems faced by the Forest Service in its early years, mainly because of public resistance. At first, ranchers balked at any kind of compliance, perceiving grazing permits as an infringement of individual freedom. They also feared that large cattle ranches and companies would secure most of the permits and squeeze out the smaller ranches of Jackson Hole. The Johnson County War of 1892 remained fresh in the memories of local ranchers. This confrontation demonstrated the antagonism that existed between the cattle kings and small ranchers. Eventually, ranchers accepted the permit system, grudgingly in some cases, for several reasons. Cattlemen saw grazing permits on the national forest as a tool to prevent sheep from entering cattle range. Furthermore, their fears of losing public grazing rights to large cattlemen never materialized. And, finally, a few ranchers recognized that unregulated grazing would destroy grasslands over time and, in turn, the cattle business. The acceptance of grazing restrictions represented a victory of conservation values over a 300-year tradition of exploitation. According to Forest Service records, Martin Henrie obtained the first permit to graze cattle and horses in the Teton Forest Reserve, reserving rights to land in the Ditch and Turpin Creeks' drainages in 1902. By 1906, officials of the reserve had issued 56 permits for 4,072 cattle and horses. [16]

|

| Robert E. Miller owned 126 cattle in 1895, and at one time had the largest herd in Jackson Hole. The Miller Ranch was on what is now the Elk Refuge. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

The cattle population is difficult to determine but, in general, ranching experienced growth in the valley through the 1930s. Elizabeth Wied Hayden conducted extensive research on this topic, gathering statistics from numerous sources. As stated earlier, William Simpson reported 100 cattle in Jackson Hole in 1883. Sylvester Wilson brought in 80 cattle in 1889, but no reliable figures exist until 1895, when numbers were reported by the Wyoming Stock Growers Association. Twenty Jackson Hole cattle men, owning 736 cattle, were members of the association. Only two ranchers owned 100 or more cattle: Brig Adams and his brother owned 100, while R. E. Miller owned 126. Other ranchers were: John Cherry, 13 cattle; John Carnes, 51 cattle; Bill Crawford, 59 cattle; Pierce and Fred Cunningham, 30 cattle; Selar Cheney, 10 cattle; Mose Giltner, 45 cattle; "Slough Grass" Nelson, 52 cattle; Ham Wort, 23 cattle; Sylvester Wilson, 41 cattle. The list may have included only association members, as some ranchers are conspicuously absent from the rolls such as Stephen Leek, Emile Wolff, and Jack Shive. In 1896, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association listed 15 ranchers and 546 cattle in Jackson Hole. Mose Giltner, who became one of the valley's largest ranchers, expanded his herd from 45 to 120 animals. By 1899, the local membership in the association grew to 28 members, owning 882 cattle. [17]

The Uinta County tax rolls for the Jackson Hole area in 1899 listed 72 cattle owners and 1,339 cattle, valued at $21,281. This figure indicates that the Wyoming Stock Growers Association included only members on their rolls; thus the numbers are low. The total number of owners is also deceptive. Very few could be called cattle ranchers compared to the scale practiced on the Great Plains. No less than 12 of the 72 owned only one cow, which may have been the family milk cow. Fourteen settlers struggled to establish a ranch with a "starter" herd of two cattle; among them were Jim Budge, John Barker, Joe Henrie, and Frank Petersen. The tax rolls suggest that few homesteaders seriously engaged in cattle ranching, as only 19 owned more than 20 cattle. The largest ranchers were Mose Giltner with 152, R. E. Miller with 198, Bill Crawford with 99 bearing his Bar over C brand, and Mary Wilson with 86 cattle. The following list is a breakdown of cattle ownership by numbers: [18]

| Number of Cattle | Owners | Percent of 72 Owners |

| 1—10 | 41 | 57% |

| 11—20 | 12 | 17% |

| 21—50 | 14 | 19% |

| 51—99 | 3 | 4% |

| 100 or more | 2 | 3% |

|

Brands

Livestock brands can cause serious confusion, because they are essentially property that can be transferred from owner to owner, along with livestock and a ranch. Branding was a practice developed to identify the ownership of livestock. Because cattle invariably wandered on the open range, ranchers needed a way to identify their livestock and deter theft. The brands used by Pierce and Maggie Cunningham illustrate the

confusion that can surround cattle brands. Over the years, people have

questioned the origin and accuracy of the Bar Flying U brand— In addition, ranch brands and names may be associated with more than one ranch, generating more confusion for researchers. For example, the Elbo Ranch was a tourist facility located on Cottonwood and Taggart Creeks in the late 1920s. The National Park Service leased the Elbo to concessioners until 1955, when it transferred the operation to the old Ramshorn Ranch located on the east side of the valley on Ditch Creek. The concessioner, Katie Starratt, took the name to the new facility, and the Ramshorn became the Elbo. |

Several inferences can be made about cattle ranching in Jackson Hole at the turn of the century. First, by 1900 the cattle population topped 1,000. Second, ownership was concentrated in the hands of a few. For example, the five largest ranchers owned 590 cattle, or 44 percent of 1,339 head; in contrast, almost three-quarters of the 72 ranchers owned less than one-quarter—304 cattle. Third, none of the Jackson Hole cattlemen, even the largest owners, could be considered cattle kings, in the sense of barons such as John Iliff or Conrad Kohrs. Last, no cattle barons established themselves in Jackson Hole.

Between 1901 and 1910, cattle numbers increased dramatically. In 1901, the Wyoming Stock Growers Association listed 29 members in Jackson Hole and 1,540 cattle; by 1910 there were 61 ranchers and 10,919 head. (These figures are low since non-members were not included on the list.) Grazing records for the Teton Forest Reserve provide different figures. For example, 39 Jackson Hole ranchers owned 3,257 head of cattle in 1906; Forest Service records issued 56 grazing permits for 4,072 cattle. Not all permittees were Jackson Hole ranchers. Forest Service grazing records listed only 4,905 cattle in the Teton National Forest in 1910, compared to the Stock Growers Association count of 10,919 head. This is a significant difference, reinforcing the difficulty in securing accurate numbers. At any rate, individual ranchers prospered over this decade. Mose Giltner doubled the size of his herd to 301 head; Joseph Henrie had increased his numbers from two to 31 animals; likewise, his neighbor, Jim Budge, had a herd numbering 35; near Spread Creek, Pierce Cunningham claimed 132 cattle in 1910 compared to 32 head in 1901. [19]

Prices increased steadily through the First World War. In 1916, no fewer than 159 cattle brands were registered in Jackson Hole. Not all of the brands represented full-fledged cattle ranches, since the list included dude ranches, gentlemen's retreats, or homesteads that were never known as working cattle ranches. The Manges place is one example. To promote the return of stray livestock, stockmen advertised their brands in the Jackson's Hole Courier. In 1918, 26 cattlemen or companies published their brands in the local paper. These lists included most of the larger ranches in the valley. [20]

Since cattle were Jackson Hole's sole export, access to markets became critical. Ranchers drove their cattle over Teton Pass or over the old Marysville Road north of Jackson Lake to railroad lines in Idaho. By 1910, the Oregon Short Line, a branch of the Union Pacific, had reached Ashton, Idaho, and by 1912, extended south to Driggs and Victor. Even Rexburg or Idaho Falls, Idaho, proved a shorter drive than the nearest railroads in Wyoming. The Union Pacific tracks passed through Rock Springs in 1868, but this was nearly 200 miles from Jackson Hole. In 1906, the Chicago & Northwestern extended tracks to Lander, Wyoming, but this was about 150 miles from Jackson Hole. Marion Allen recalled participating in a cattle drive to Hudson, Wyoming, a town on the Lander Line in 1920, where D. E. Skinner and other Blackrock grazers hoped to secure better prices. But the trails over Teton Pass and the Ashton-Marysville roads remained the primary routes. For example, in 1917, 42 carloads of cattle were driven over Teton Pass to Victor in early October, most of them owned by Preston Redmond and Roy McBride. Jim Francis, a prominent cattleman in Spring Gulch, drove his cattle to Victor every year from 1913 through 1944. [21]

Cattle ranching thrived in the valley as prices increased between 1900 and 1919. A chart listing the price of calves per hundredweight records steady increases between 1910 and 1919. Although the accuracy of cattle counts are suspect, they indicate that ranching and grazing increased significantly in these years. Cattle grazing on the Teton National Forest tripled from 5,229 head in 1908 to 15,284 in 1917. According to these records, the number of cattle broke 10,000 first in 1916, when 12,591 cattle grazed in the forest. During this period calf prices increased from $7.30 per hundredweight in October 1910, to $10.20 in October 1916, and $12 in October 1917. Figures from October or November were used, because most ranchers sold their stock after the fall round-up. Ranchers lived and died by market prices and were quick to complain about declines. In November 1917, the Courier described the prices of cows and steers as meager, despite the fact that prices were good during this period.

After the end of World War I in 1918, the prices for agricultural products plummeted as demand declined and the federal government dropped price supports. In Jackson Hole, the drought of 1919 ruined crops, crippling both ranchers and farmers. In 1918, a rancher who sold calves in October received $12.10 per hundredweight; in 1919, he received $10.60 per hundredweight, a difference of $1.50. The next year brought even worse news as calves sold for $10.00 per hundredweight in October and $9.60 in November. Despite falling prices, cattle broker W. J. Kelly described a top market at Omaha, and passed on compliments concerning the quality of Jackson Hole cattle. In 1921, Kelly reported a slow market, partially caused by the availability of corn-fed beef from the Midwest. Calf prices plummeted to $7.50 per hundredweight in October, and $7.40 per hundredweight in November. [22]

From 1921 through 1926, cattle prices remained poor. By 1924, only 16 ranches advertised brands in the Courier, down from 26 in 1918. Within the national forest, cattle grazing declined from 15,284 head in 1917, to 6,594 cattle in the Teton County section of the forest in 1926. Although the last figure does not include all cattle grazing on forest lands, it suggests the severity of cattle ranching's slide. Furthermore, a 1925 petition signed by 97 landowners, many of them cattlemen, was prompted in large part by the agricultural depression of the 1920s. This petition supported the creation of a preserve or recreation area in Jackson Hole and the Teton Range, and the willingness of the signers to sell their lands. [23]

Prices increased between 1927 and 1929 with prices per hundredweight topping $10 for the first time since 1920. Struthers Burt wrote to Horace Albright that "the cattlemen, for the first time in years, expected to make money." More important, Burt noted that the "dejected state of mind" that had gripped the valley for several years was gone. [24] In August 1928, the Courier reported that the cattle market had improved, and some stockgrowers held their herds hoping to build up higher prices "to clear up past obligations," a euphemism for debts. By early October, Jackson Hole ranchers had shipped 100 carloads of cattle from Victor, while another 37 carloads of cattle were being trailed over Teton Pass. In that month, calf prices were $12.40 per hundredweight. The next year, the October price reached a high of $12.50 on the 15th. On October 24, 1929, stock market prices collapsed, and the day, known as Black Thursday, marked the beginning of the worst depression in the nation's history. [25]

Calf prices plummeted from $12.60 in 1929 to $8.30 per hundredweight in October 1930. The bottom fell out as prices nosedived to figures unheard of since the turn of the century. The prices per hundredweight were as follows:

| October | November | |

| 1931 | 6.00 | 5.70 |

| 1932 | 4.60 | 4.50 |

| 1933 | 4.10 | 4.55 |

| 1934 | 4.60 | 4.10 |

The Great Depression hit Americans hard; but unlike most of the nation, ranchers and farmers had contended with an economic depression since the 1920s. [26] Cattle ranching declined in the 1930s, not only because of the depression, but the land acquisition program of the Snake River Land Company. The company purchased more than 30,000 acres between 1928 and 1933, much of it belonging to prominent ranchers. Cattle populations remained relatively stable in Teton County, because even though there were fewer ranchers, they owned larger cattle herds to survive lean years and prosper in good years. The cattle population of Teton County remained stable from 1936 through 1942: 1936, 10,838; 1937, 12,307; 1938, 10,604; 1939, 10,906; 1940, 12,337; 1941, 12,129; and 1942, 12,580. [27]

The advent of World War II brought hell to earth for eight years, but for American agriculture it brought prosperity as worldwide demand for foodstuffs escalated. War began with the Japanese invasion of China in July 1937, followed by the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. By the end of 1941, the war had boosted cattle prices; in September, calves per hundredweight fetched $10 for the first time since 1930. The cattle industry thrived for the next two decades. [28] Like ranching in the American West, world events and economic conditions influenced the cattle business in Jackson Hole as much as local factors.

Cattle ranching in Jackson Hole followed patterns that occurred elsewhere in the West, including stock improvement. Cattlemen imported improved breeds by the 1870s. Wyoming cattlemen introduced English Herefords in 1878. No record was found of the first breed of cattle brought to Jackson Hole, but ranchers were undoubtedly influenced by the trend of improving the quality of herds through selective breeding. Elizabeth Hayden determined that the Wilson brothers introduced the first purebred Hereford bulls in Jackson Hole in 1901. Hereford and Black Angus became the predominant breeds in the valley. In 1914, Bill Kelly purchased a Durham bull for Harold Hammond of the White Grass, who intended to establish a cattle ranch. Gerrit Hardeman, a Dutch immigrant, bought the Charles E. Davis homestead in 1919 for $2,500 and established one of the finest herds of Hereford cattle in the region. [29]

Cattlemen's associations were also important to ranchers in Jackson Hole. These associations represented the cooperative spirit of the westering experience. In the 1890s, a number of Jackson Hole ranchers belonged to the Wyoming Stock Growers' Association, an organization formed to promote industry interests. Membership of Jackson Hole cattlemen in this state organization expanded from 19 in 1895 to 35 by 1910. In practical terms, local associations were more important. Ranchers formed these organizations based on common grazing allotments such as the Gros Ventre River or Blackrock Creek areas. Communal roundups and drives to and from grazing ranges required cooperative efforts. Groups of ranchers pooled money to hire line riders to watch cattle on summer range. At least one line shack, built to house hands, is extant in the Sportsman's Ridge area in Teton National Forest. [30]

|

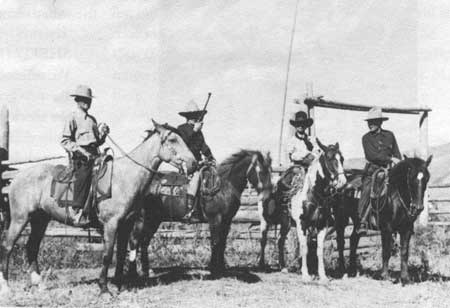

| Cattlemen's associations were formed in Jackson Hole to address specific problems, such as predators. This photo shows a group of early Spring Gulch ranchers. Left to right: Bert Charter, Harry Harrison, Jim Boyle and Jim Francis. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Protecting cattle from predators, in particular the gray wolf, seems to have been the major motive for creating livestock associations in the valley's early years. On May 21, 1914, the Courier reported that 15 wolves had killed a cow and four yearlings being trailed to summer range on the Gros Ventre. The cattle belonged to Preston Redmond. The next week Roy McBride and Redmond herded their cattle together to protect them from wolves and hired Jess Buchanan to watch the cattle at night. While at Crystal Creek, Buchanan reported that wolves would harass cattle on one side, while he patrolled the opposite side. Cowpunchers also stated that wolves pursued a "favorite pastime" of biting off the tails of calves. Wolves may have tried this as an alternative to hamstringing the animals, that is, bringing prey down by their hindquarters. In June, Roy McBride set out to hunt down the wolf packs. In July, ranchers formed the Fish Creek Wolf Association specifically to eradicate the wolf population on the Gros Ventre River. They hired Walter Dallas to hunt them, paying him $22 per month. In addition, they agreed to pay a bounty: $62 for a "she-dog," $52 for dogs (males), and $22 for pups. The association offered a $1.50 bounty for coyotes. To pay Dallas's wage and bounties, the association assessed each member 12 cents per head of cattle. This program eliminated the gray wolf in the area by the early 1920s. [31]

Jackson Hole cattle associations also formed to promote ranching interests. In 1921, valley residents created the Jackson Hole Cattle and Horse Association, which remains active today, though hindered by dwindling membership. Early in 1925, several ranchers announced the formation of a new group called the Jackson Hole Cattle and Game Association. To recruit new members, the association guaranteed that the group would not promote the Yellowstone extension, nor serve as a tool for political purposes. Organizers adopted the following goals: oppose opening new areas in Teton National Forest to sheep; oppose further unnecessary grazing restrictions; and oppose destruction of game and commercialization of forests, lakes, and streams. [32]

Stories of range wars between sheepherders and cattlemen are entrenched firmly as a violent chapter in western lore. Tales of Jackson Hole cattlemen banding together to drive "woolies" out of the valley date from the turn of the century. One story has it that a sheepherder was murdered at the upper end of Death Canyon, the source of its name. No evidence has been found to confirm this story. Sheepherding increased in the American West in the late 1890s, causing competition and conflicts over grazing range. Confrontations became so violent in Wyoming that historian T. A. Larson rated the range wars between cattlemen and sheep ranchers as "a major theme of the state's history." Between 1897 and 1909, 16 people were killed and possibly 10,000 sheep destroyed in Wyoming. But, like many violent incidents in history, the stories grew bloodier with time, obscuring an accurate record of events. [33]

As ranchers introduced sheep—or cattlemen switched to raising them—Jackson Hole ranchers became concerned. Sheep appeared in adjacent areas such as Star Valley, Teton Basin, and the Green River country. In 1897, local ranchers reportedly published a notice in a newspaper warning that "no sheep will be allowed to pass through Jackson's Hole . . . under any circumstances." S. N. Leek recalled that ranchers posted signs along the approaches to the valley warning sheep drovers to stay out.

SHEEPMEN, WARNING

We will not permit

sheep to graze upon

the elk ranges on

Jackson Hole. Govern

yourselves accordingly

Signed:

The Settlers of Jackson's Hole

|

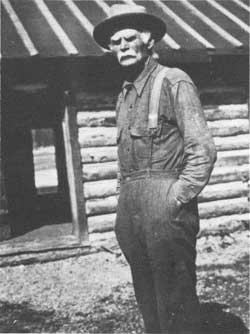

| Stephen Leek, cattle rancher, conservationist and entrepreneur. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Settlers in the valley followed the general pattern of range conflicts elsewhere in the West; they warned sheepmen that certain areas, in this case Jackson Hole, were off limits, then set boundaries that sheep were not to cross. Confrontation was the most serious phase. S. N. Leek and Lee Lucas remembered that several herds of sheep crossed Teton Pass, but were turned back by well-armed cattlemen at the Snake River. Sheep that had already crossed the river were escorted out of the valley over the Gros Ventre. Specific dates and participants are not known. A. A. Anderson, the first supervisor of the Yellowstone Timber Reserve, drew the rancor of sheepmen when he restricted their grazing rights and drove them off rangelands, where they had no permits. Because Jackson Hole is an enclosed valley, keeping sheep out was relatively easy. [34]

No violent confrontations between sheepherders and ranchers occurred in Jackson Hole. In the upper Green River Valley, cattle ranchers faced off against sheepherders around the turn of the century; they killed a large number of sheep around 1902. Esther Allan reported that 2,000 sheep were killed in one case and 800 in another. Whether these were the same incidents and conflicting figures, or represent separate incidents, is unknown. Another confrontation occurred when A. A. Anderson received information from Washington, D.C., that 60,000 sheep had been turned loose in the Teton Division of the Forest Reserve. The sheep belonged to four owners—and were reportedly guarded by 40 armed herders. Anderson gathered and deputized 65 well-armed men at a place called "Horse-creek" near Jackson Hole and moved out to confront them. They found 1,500 sheep and several herders and escorted them across the eastern boundary of the reserve. There is no evidence that the sheep entered Jackson Hole. [35]

Sheep were introduced in Jackson Hole later without violence, possibly because of two factors. In 1909, a group of masked men attacked a sheep camp near Tensleep in the Bighorn Basin, murdering two wealthy sheep ranchers and a herder. Woolgrowers associations put up reward money, while the county sheriff and prosecutor aggressively investigated the case. The sheriff arrested seven men; two provided state's evidence which resulted in the conviction of the other five, who received sentences ranging from three years to life in prison. The Tensleep incident served notice to cattlemen that protecting grazing lands with a gun, a holdover from the free-for-all days of the open range, would no longer be tolerated. Second, after 1919, raising sheep became more attractive to stockmen; sheep provided two crops per year, wool and meat, an attractive prospect during a depression. [36]

In June 1923, the Jackson's Hole Courier reported sheep in the valley, introduced by J. G. Imeson in South Park. The article stated that sheep might be important in the future, because the sheep market was good while cattle prices remained depressed. In 1926, Lewis Fleming, ostensibly a cowpuncher, reported grazing 450 sheep on his 640-acre stock-raising entry south of the JY. By the 1930s, in the heart of the Great Depression, several Mormon Row farmers and ranchers had introduced sheep, notably Joe May, Clifton May, and Hannes Harthoorn. They grazed sheep on Blacktail Butte and on their own land. Sheep trails to summer ranges also crossed the valley and the Teton Range. In September 1929, Sam T. Wooding, the superintendent of Grand Teton National Park, encountered 1,742 sheep being herded from Fox Creek over Fox Creek Pass to the head of Teton Creek. Since the trail crossed Death Canyon Shelf in the park, Woodring gave the owner, a man named Taylor, permission to pass through park lands, stipulating only that no stops be made. The 1929 enabling legislation for the park grand-fathered in existing livestock drifts and grazing. [37]

Some resented the presence of sheep in the valley, but limited their hostility to verbal barbs and letters. Joe R. Jones complained to the editor of the Courier that sheep destroyed valuable elk and cattle range and introduced ticks in the valley. Gladys May Kent recalled some prejudice against sheep; as a schoolgirl, during the course of an assignment to write poetry, Mrs. Kent recalled a rhyme dedicated to her: "There's a freckle face girl who lives over the way, her dad's a sheep herder, her last name's May." She also remembered a dog killing sheep on Mormon Row, but could not confirm if it was deliberate on the part of the dog's owner. [38] In 1932, Dick Winger, the field manager for the Snake River Land Company, reported sheep loose on company lands:

I went to the Kafferlin place above Kelly in my car today, where I served in the capacity of sheep herder. Our good friend, Hannes Harthoorn, has run out of feed and turned his sheep out along the warm springs ditch. I am now trying to prepare proper notices for the sheep owners in that section, which will induce them to keep the "range maggots" off of our property—and still like me. [39]

While residents raised sheep in Jackson Hole, they never replaced cattle, nor were their numbers very large. For example, in 1950, four ranchers owned 815 sheep; by 1954 the number had dwindled to 104. [40]

Larger land and cattle companies eventually dominated ranching in Jackson Hole, another common pattern in the West. As America moved into the twentieth century, the size of cattle ranches grew as the bigger ranchers bought out smaller stockmen. Two dudes named Moser and Trexler bought a ranch near Wilson around 1900. Moser wanted to buy up land in the valley, believing he would eventually make a killing in real estate rather than cattle. He died around 1914 before he could implement the plan. Consolidation began in World War I and accelerated during the hard decades of the 1920s and 1930s. Around 1900, a rancher could get by on 320 acres and about 100 cattle. By the 1920s, ranchers increased the size of their outfit to perhaps 640 acres, plus a sizable grazing allotment on the national forest, and 450 to 500 cattle. Lee Lucas came to Jackson Hole in 1896 and gradually built up a premier ranch in Spring Gulch. By the 1930s, he owned 640 acres and maintained a herd of 450 Herefords and 50 horses. James Boyle bought a large ranch in South Park around 1917, purchasing 1,214 acres for $17,000. P. C. Hansen bought the Fisk place in Spring Gulch after 1900. Over the years, the Hansen family built up their ranch, until they owned more than 3,500 acres in Spring Gulch by the 1940s. [41]

|

| Feeding elk at the Hansen Ranch in Spring Gulch, ca. 1911. Ranchers usually tried to keep the elk from eating their hay, but fed the wildlife during the harsh winters. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

Outside entrepreneurs tried to establish two large cattle ranches after 1910 on lands that presently comprise the park. D. E. Skinner, a Seattle shipbuilder, bought land in the Buffalo Fork area, which formed the nucleus of the Elk Ranch. Chester Pederson, related to the Remington firearms family, established the JP Ranch in the lower Gros Ventre River area.

Skinner came to Jackson Hole around 1912 to hunt. Guided by Jim Budge, he was impressed with the valley's potential for cattle ranching. In 1916, he bought the 320-acre Otto Kusche ranch for $14,000; in 1919, he bought Jack Shive's Hatchet Ranch on the Buffalo Fork, about 750 acres for $20,000. Skinner formed a partnership with Val Allen and purchased his property west of Uhl Hill in 1917 for $6,500. Allen managed the would-be cattle empire for two or three years, then broke off with Skinner. Another settler, Tom Tracy, took over as foreman of the ranch and managed Skinner's sawmill. The Elk Ranch Company started with 450 cattle around 1915, and built up the herd to more than 2,000 cattle by 1919. In 1920, Skinner sold the Elk Ranch to J. D. "Si" Ferrin, with the exception of the Hatchet Ranch formerly owned by Jack Shive. [42]

Meanwhile, Ferrin had begun to build his cattle empire on a homestead west of Uhl Hill. Settling the property around October 1908, Ferrin and his family cleared 50 acres, raised timothy for hay, and built a house, corrals, barns, and other outbuildings. Ferrin valued the improvements at $5,000. In 1914, he secured a lucrative contract to supply beef to the Reclamation Service at the Jackson Lake Dam. Ferrin purchased other homesteads in the vicinity of his ranch, buying the Thompson homestead in 1911, Joe Heniger's place in 1914, Marius Kristensen's property in 1918, the Elk Ranch in 1920, the McInelly's 520 acres in 1927, and the old Thornton homestead in 1928. [43]

The Ferrins prospered during these years. A large family, Si and Emmeline Heniger Ferrin had five sons before she died in 1904. Ferrin married Edith McInelly in 1905, and they had nine more children, four sons and five daughters. As the sons came of age, they took up homesteads, adding to the Ferrin empire. Curtis Ferrin filed a 160-acre entry in October 1917, just before he enlisted in the army. He later died of influenza in Europe. Leonard Ferrin filed a 640-acre stock-raising entry in 1920, grazing 400 cattle on the tract for two months per year. Cyrus Ray Ferrin filed a stock-raising homestead in 1923, grazing 200 head of cattle and horses on the property each summer. [44]

After he bought out Skinner, Ferrin purchased 800 yearlings and 1,100 calves. During the 1920s, the Ferrins owned between 1,200 and 2,000 head of cattle. The Elk Ranch was the largest outfit in Jackson Hole during these years. Despite or perhaps because of depressed cattle prices, Ferrin mortgaged his property for a total of $205,362 to finance his operation. According to county records, he paid off the loan, except for $15,000. At the old Kusche homestead, Ferrin installed a water-powered sawmill and constructed frame buildings that included a house, barns, machine sheds, and shops. According to Ferrin's daughter, Ada Clark, the house burned. [45] Three frame buildings and a concrete spring house remain at the site today. By the time the family sold their holdings to the Snake River Land Company in 1928 and 1929, Si Ferrin owned 1,708.74 acres, Ray Ferrin had 643.57 acres, Leonard Ferrin had 640 acres, and the family owned another 640 acres, for a total of 3,629.09 acres. The company paid them $114,662.12 for their land and improvements. [46]

Ferrin divided the money among his family and invested in cattle, starting a feedlot operation in Sugar City, Idaho. From 1929 through 1933, his son Merritt Ferrin ran the feedlot. Si Ferrin went bankrupt during the depression. According to Ada Clark, he lost everything in the stock market collapse of 1929. Other sources suggest that Ferrin went bankrupt in the early 1930s. Calf prices dropped to $6 per hundredweight in October 1931, then to $4.06 the next year. Ferrin never quite recovered from the blow and this, along with poor health and accidents, "caused Cy [sic] to cease all active pursuits." [47]

|

| Elk Ranch, headquarters, ca. 1940s. Si Ferrin built up the Elk ranch to be one of the biggest in the valley by the 1920s. By the time the Ferrin family sold the ranch in 1928, they owned 3,629 acres. Grand Teton National Park. |

In his last years Ferrin worked for his brother-in-law, Ben Goe, at the Cowboy Bar in Jackson as a night watchman, and a shill at the gaming tables. According to one popular story, one morning he mistook his reflection in the mirror behind the bar for an intruder, drew his sidearm, and shot out the mirror. However, Ferrin should be remembered for his success as a farmer, a game warden and, for a time, as a cattleman. If Jackson Hole ever had a cattle baron, Si Ferrin perhaps fit the role as well as any other rancher in the valley. [48]

The Snake River Land Company fenced their holdings in this area and continued to raise hay. Thus, the Elk Ranch of the 1930s and 1940s encompassed the Ferrins' land and other ranches as well. In the 1940s, the Jackson Hole Preserve leased the property for cattle ranching to support of the war effort. Today, the National Park Service leases much of the Elk Ranch for grazing, as part of a land exchange made in the 1950s.

J. D. "Ted" and Chester Pederson began consolidating ranches in the Gros Ventre River area in 1909, forming the JP Ranch Company. Ted Pederson's interest in Remington Arms kept him in the East for most of the year; nevertheless, his family formed the JP Ranch Company and initiated an ambitious land acquisition and development program. Beginning with the Joe LaPlante homestead in November 1909, J. D. Pederson began purchasing homesteads south of the Gros Ventre River. The next year, Maggie Adams sold her 320-acre tract to the JP Ranch. "Chess" Pederson received a patent to a homestead entry on Botcher Hill. In 1920 they added the Agnes Geisendorfer and August Romey homesteads farther up the Gros Ventre River. By then, the JP Ranch consisted of more than 1,600 acres south of the Gros Ventre River. [49]

|

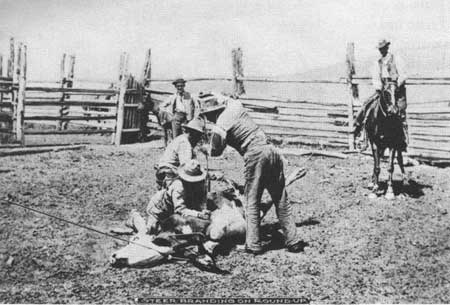

| Branding at the Elk Ranch. By 1918, 26 cattlemen had published their brands in the Jackson's Hole Courier. Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum |

The JP Ranch also invested considerable sums of money into their operations. Early in 1914, they purchased a new oil tractor for the spring planting season. This machine was responsible for the mysterious noises that echoed throughout the upper Flat Creek area, arousing both fear and curiosity among the homesteaders. In 1920, the Courier reported that the JP Ranch had launched an extensive improvement program. Carpenters built a bunkhouse, tool shed, barns, and remodeled several houses. To improve the irrigation system, five wells were drilled, and ditches were dug to bring water to 1,500 acres of land. Also, the Pedersons constructed a large two-story log home, one of the finest in the valley. [50]

The family soon got into financial trouble. First, the slump in cattle prices in the 1920s cut the potential income of the ranch. Second, they overextended themselves, buying too much land and investing too much money into improvements. The Pedersons mortgaged their lands in the 1920s, and in 1929, Mr. C. Bakker, a citizen of the Netherlands, initiated foreclosure proceedings for failure to pay a $15,000 mortgage taken out in 1917. The Snake River Land Company purchased the outstanding mortgages, paid off liens on the JP lands, and secured quit-claim deeds from the family and outside parties with financial claims. The company spent a minimum of $17,887.75 in securing the JP Ranch. They certainly spent more, but company records of this transaction are incomplete. By 1927, the Pedersons gave up on the ranch and moved to Idaho Falls, Idaho. The rise of the JP Ranch Company between 1910 and 1920 was significant. The Pedersons could have developed one of the largest ranches in the valley, but their financial collapse was the most notable bankruptcy in Jackson Hole during the 1920s. [51]

While the JP Ranch failed, there were success stories as well. Gerrit Hardeman immigrated to the United States in 1910 at the age of 19. Born in Teerseen, Netherlands, in 1891, Hardeman was the youngest of ten children. After working in Iowa for a year or two, he came to Jackson Hole in 1911 or 1912. He worked at a variety of jobs for R. E. Miller and others as a farm laborer, teamster, and timber cutter, saving as much of his wages as possible. In 1919, Hardeman had saved enough to buy the 160-acre dryland farm of Charles and Helena Davis for $2,500.

In 1915, the Davises had homesteaded a quarter section in the eastern portion of today's park, about one mile south of Ditch Creek. Davis filed final proof papers in 1918; his improvements included a one-room log cabin (14 x 16 feet), a stable (18 x 24 feet), a potato cellar (10 x 12 feet), 35 acres cultivated for oat hay, and a three-wire post fence and a three-pole, one-wire, buck fence. Hardeman continued to work at other jobs while he cultivated crops on his farm. He planted a crop each spring, then hauled freight for customers, among them the Reclamation Service, the Sheffields at Moran, Jimmy Simpson, who owned the Kelly Store, and the Kneedys, who established the valley's only flour mill at Kelly. In 1922, Hardeman married Alta Lamar Crandall, the daughter of the Crandalls who owned the old Lee Roadhouse on the Teton Pass Road.

Moving onto the Davis homestead, the Hardemans made the place as self-sufficient as possible. They raised chickens, kept a cow to provide milk and butter, raised a large garden, and canned up to 300 quarts of peaches, and 100 quarts of elk meat per year. Gerrit Hardeman suffered several setbacks in the early years. The drought of 1919 wiped out his first crop. This disaster forced Hardeman to cut native grass from the meadowlands near Moran to provide feed for his teams. In the 1920s, the newlyweds started raising cattle. When they shipped their first steers to Omaha, they expected to realize a tidy return. Instead, Hardeman received much less than he had anticipated and suspected that the commission men contracted to sell the cattle had taken advantage of him. In June 1924, a fire swept through the homestead. A spark from the cook-stove chimney ignited a pile of straw and quickly spread out of control. The fire destroyed the barn, storehouse, and granary; in addition, they lost their chickens and $1,000 worth of grain. Gerrit and Lamar Hardeman could have given up, but they rebuilt the ranch.

In June 1926, Hardeman filed papers on a 280-acre relinquishment located in Section 25, adjacent to his homestead. From 1927 through 1929, he cleared and cultivated 45 acres, raising grass clover for livestock. The improvements consisted of a one-room log cabin (18 x 20 feet) built by the previous occupant, a barn (12 x 16 feet), a corral, and a three-pole, one-wire buck fence. The General Land Office issued a patent for the acreage on June 4, 1930. The Hardemans added to their holdings in 1943, when they purchased the Luther Taylor homestead for $2,600, plus added another 40 acres owned by William Taylor. On their 640-acre ranch, the Hardemans and their sons built up one of the finest cattle ranches in Jackson Hole. Determined never to be dependent on cattle brokers again, Hardeman decided to raise purebred Hereford cattle and sell them locally to ranchers who sought to improve the quality of their stock. The family built a solid reputation in the regional cattle industry for the quality of their Herefords. In 1948, experts from the University of Wyoming proclaimed their cattle among the best in Wyoming.

In 1955, the Hardemans sold their ranch to the National Park Service for $100,000 and moved their outfit to a ranch at Wilson, Wyoming. Their sons, Earl and Howdy Hardeman, continued to operate one of the few remaining ranches in Jackson Hole into the 1990s. They have since retired, selling some of the ranch for subdivisions and renting the remainder of the ranch. Much has been written about the thousands of immigrants who settled the West only to be broken by an unpredictable environment, economic conditions, and growing corporate control of the land and resources. Gerrit and Alta Lamar Hardeman's experience tells another story. A 19-year-old native of the Netherlands came to the United States and through hard work, thrift, and sound management established one of the best ranches in Jackson Hole. Others who developed ranches through individual efforts that were known for the quality of their livestock were Walter and Ed Feuz, James Boyle, Peter Hansen and later Clifford Hansen, Rod and Phil Lucas, Bruce Porter, Amasa James, Boyd Charter, and Jim Imeson. [52]

The emergence of "gentlemen ranchers" began in the 1930s. These were people who had made fortunes in other enterprises, bought up cattle ranches and other lands for a variety of reasons—but did not depend on cattle ranching for their livelihood. Many had been introduced to the valley as guests at dude ranches. Stanley Resor made a fortune as president of one of the world's most prominent advertising agencies, the J. Walter Thompson Company. In the 1920s and 1930s, he bought up ranches north and south of Wilson, Wyoming, establishing one of the valley's largest ranches. In the north end of the valley along the Buffalo Fork, the Cockrell family, who earned a fortune in the oil business, bought the Noble Gregory Ranch in 1942 and continued to raise cattle.

Bill and Eileen Hunter purchased the old Jim Williams ranch from Ida Redmond in 1946. The Hunters retired from the retail auto sales business in 1950 and moved from Kemmerer, Wyoming, to their ranch, "where they planned to spend the rest of their lives enjoying a well-earned vacation." As a hobby, they decided to raise Herefords and purchased some from Gerrit Hardeman. Most of the present buildings were designed by a Salt Lake City architect and constructed in the late 1940s. Bill Hunter died in 1951, scarcely a year after retirement. Mrs. Hunter sold out to the National Park Service and spent summers on the ranch until her death in 1985. [53]

Cattle ranching has declined in Jackson Hole over the last 30 years. Land values skyrocketed as the town of Jackson developed a tourism-based economy and the community has pushed to expand the tourist season from three months to year round. In particular, the construction of Teton Village in the 1960s accelerated this trend. Coupled with difficult economic times for agriculture, escalating land prices have proven irresistible to ranchers, who have sold all or portions of their ranches for resorts or residential subdivisions.

Over the long term, the future of cattle ranching is bleak in Jackson Hole. Earl Hardeman summed up the current state of the cattle business succinctly. He believed that Jackson Hole ranchers raised "cattle as good as you'll find anyplace in the world . . ." but cited the high overhead of ranching caused by the need to feed cattle six months per year as a cause for the decline. Further, as ranchers sold out, mutual support declined. Hardeman believed this made it more difficult for ranchers as "you kind of need to be in a place where there are all cow people. You know, it's just better if you all have the same kind of problems. Now, we're ranching in a subdivision really, and it creates a lot of problems." Moreover, ranches no longer are as self-sufficient as in the past. "We once had more ways of really trying to make it. We had the garden, we had the milk cow, we had the pigs. Now we go to the supermarket," Hardeman observed.

If this ground is as valuable as they say it is, there's no way that I can see that our kids are going to stay here and keep ranching. I hope they are not that dumb. Us old fellows . . . we'll probably ride it out, but the kids aren't going to do it. I mean they're going to put her in the bank and go on down the road.

In 1986, Hardeman predicted that "in 20 to 25 years, there won't be another mother cow raised in Jackson Hole." [54]

Ranching also had a significant impact on the ecology of Jackson Hole. Cattle ranching represented an adaptation to the land west of the 100th meridian, as ranchers introduced techniques such as irrigation and dry farming, as well as domestic livestock and plants. Grazing affected the native vegetation, while overgrazing depleted range land. Settlers displaced or eradicated wildlife. Wolves were exterminated systematically to extinction. Settlers plowed and fenced lands that served as migratory routes and winter range for elk and pronghorn. Today, the Jackson Hole elk herd survives on one-quarter of its historic winter range, and must be fed during the severest winter days at the refuge. Up to 1906, settlers reported an annual migration of pronghorn, more commonly known as antelope, into the valley. W. C. Deloney recalled that hundreds of antelope migrated into Jackson Hole from the Green River Valley via the Hoback. At Granite Creek, the herd split. One group crossed the divide into the Cache Creek drainage; the other herd followed the Hoback into Jackson Hole. Deloney described the migration as a string consisting of thousands of animals that took several days to pass his store at the Jackson townsite. Although accepting his estimate of numbers takes some credulity, other accounts confirm Deloney's story, with the exception of his estimates. The antelope failed to return in 1907. Only strict protective regulations restored the antelope to Jackson Hole in the 1950s. In 1906, the Wyoming pronghorn population was 2,000; in 1952, it numbered 100,000. In 1958, the Grand Teton National Park Superintendent's Report for June confirmed antelope sightings in the Antelope Flats area and near the Jenny Lake Store. [55]

Cattle ranching is most important to the valley's history because it anchored early settlement in the valley, providing an economic base and the stability needed to establish viable communities. Ranching became and remained the economic mainstay through the World War II, when the tourist industry displaced it. The rancher and cowpuncher left a tradition that continues to be an important element of Jackson Hole's self-image.

Notes

1. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 457-466.

2. Merk, History of the Western Movement, p. 464.

3. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 582-590; and Merk, History of the Western Movement, pp. 457-466.

4. Billington, Westward Expansion, p. 590.

5. Ibid; and Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 163-194.

6. Billington, Westward Expansion, pp. 596-597; and Merk, History of the Western Movement, p. 463.

7. Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 190-192.

8. Merk, History of the Western Movement, pp. 464-466.

10. Hayden, From Trapper to Tourist in Jackson Hole, p. 54.

11. Larson, History of Wyoming, p. 193; and Merk, History of the Western Movement, p. 464.

12. Gillette, Homesteading with the Elk, pp. 135-141; and Jackson's Hole Courier, November 8, 1945.

13. Homestead Patents, Homestead Certificate 529, Lander, Fred Lovejoy, 1904.

14. Homestead Patents: 36433, J.P. Cunningham, 1908; Homestead Cert. 1181, Evanston, J.P. Cunningham, 1904. Estimates of hay consumption by cattle were corrected, based on information provided by Virginia Huidekoper, Earl Hardeman, and Jack Huyler.

15. Struthers Burt, Diary, p. 116.

16. Allan, "History of the Teton National Forest," pp. 125, 154; Jackson's Hole Courier, February 17, 1949; and Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 268-284.

17. Elizabeth Wied Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Cattle, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

19. Ibid., Allan, "History of Teton National Forest," p. 158.

20. "Jackson Hole, Wyoming Cattle Brands," File B, Brands, acc. no. 481, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Jackson's Hole Courier, October 18, 1917, and February 7, 1918.

21. John Markham, "Cattle Drives," unpublished manuscript (Ms 167G), Wyoming State Archives Museums and Historical Department; Driggs, History of Teton Valley, p. 184; Allen, Early Jackson Hole, pp. 117-154; and Jackson's Hole Courier, October 11, 1917.

22. Allan, "History of Teton National Forest," p. 158; "Calves Prices," File MM, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Jackson's Hole Courier, November 1, 1917, October 28, 1920, and August 25, 1921.

23. "Calves Prices," File MM, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Jackson's Hole Courier, May 22, 1924, and January 27, 1927; and Allan, "History of Teton National Forest," p. 158.

24. "Calves Prices," File MM, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Struthers Burt to Horace Albright, October 14, 1927, Horace Albright Papers, 1923-1927, Yellowstone National Park Archives.

25. Jackson's Hole Courier, August 16, 1928, and October 11, 1928.

26. "Calves Prices," File MM, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

27. "Hearings on H.R. 2241," 1943, 383.

28. "Calves Prices," File MM, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

29. Larson, History of Wyoming, p. 167; Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Ranching Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and Office of the Teton County Clerk and Recorder, Deed Record Book 2, p. 15, Charles and Helena Davis to Gerrit Hardeman, Warranty Deed, April 16, 1919.

30. Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 168-171; and Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Ranching, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

31. Jackson's Hole Courier, May 21, 1914, May 28, 1914, June 11, 1914, and July 9, 1914. The actual level of predation by wolves is a sore subject, particularly between livestock interests and environmental groups. While reports of mortality may well have been exaggerated or mistaken for predation, they should not be discounted out of hand either. It is doubtful that ranchers would have put up so much bounty money had they not experienced losses.

32. Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Cattle, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Jackson's Hole Courier, March 19, 1925.

33. Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 369-372.

34. Ibid; and Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Sheep, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

35. Allan, "History of Teton National Forest," pp. 125-131.

36. Larson, History of Wyoming, pp. 371-372; and interview with Don and Gladys Kent by Jo Anne Byrd, #18, in "Last of Old West Series."

37. Jackson's Hole Courier, June 7, 1923; Homestead Patents: 1038450, Lewis Fleming, 1929; interview with Don and Gladys Kent, #18; and Superintendent's Monthly Report, September 1929, Grand Teton National Park.

38. Jackson's Hole Courier, June 7, 1923; and interview with Don and Gladys Kent, #18.

39. Rockefeller Archive Center, Harold P. Fabian Papers, 1V3A7, Box 6, File 35, Richard Winger to Josephine Cunningham, April 24, 1932.

40. Hayden Collection, Subject File #5, Cattle Ranching, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum.

41. Nellie Van Derveer, "Teton County-Agriculture and Industry," WPA File 1327, Wyoming State Archives; interview with Phylis Brown by Jo Anne Byrd, #4, "Last of Old West Series;" and Jackson Hole Platbook, Snake River Land Company, Harold and Josephine Fabian Collection, Grand Teton National Park.

42. Jackson's Hole Courier, January 4, 1934; Teton County Records, Deed Record Book 3, 189, Jude Allen to Elk Ranch Company, Warranty Deed, December 18, 1917; Deed Record Book 3, p. 137, John S. Shive to D. E. Skinner, Warranty Deed, March 26, 1919; Deed Record Book 3, 446, p. Otto Kusche to D. E. Skinner, Warranty Deed, September 1, 1916; John Markham, "The Hatchet and Elk Ranches" (ms. 167F, H70-135/4), Wyoming State Archives; and Deed Record Book 2, 124, Frank S. Coffin to J. D. Ferrin, Warranty Deed, December 4, 1915.

43. Homestead Patent 323588, J. D. Ferrin, 1912; Teton County Records, Deed Record Book 1, p. 302, W. A. Thompson to J. D. Ferrin, Warranty Deed, July 17, 1911; Deed Record Book 3, p. 212, Joseph Heniger to J. D. Ferrun, Warranty Deed, January 3, 1914; Deed Record Book 2, p. 218, J. D. Uhl to J. D. Ferrin, Warranty Deed, April 26, 1918; Deed Record Book 2, p. 409, James and Opal McInelly to J. D. Ferrin, Warranty Deed, October 13, 1927; Deed Record Book 2, p. 293, D. E. Skinner to Leonard J. Ray, and Robert L. Ferrin, Warranty Deed, December 9, 1920; and Jackson's Hole Courier, September 3, 1914.

44. Interview with Ada Clark by Jo Anne Byrd, #8, "Last of Old West Series;" Jackson's Hole Courier, April 13, 1944; and Homestead Patents: 895259, Heirs of Curtis Ferrin, 1922; 958787, Leonard Ferrin, 1924; and 1028708, Cyrus Ray Ferrin, 1928.

45. Teton County Records, Index Book, T. 44 N., R. 114 W., 6th PM.; interview with Ada Clark, #8. According to Ada Clark, her father and family owned as many as 5,000 cattle at one point.

46. Teton County Records; Fabian Papers, RAC, Box 21, Files 217, 218, 220, 221, all Ferrin parcels; Deed Record Book 2, p. 461, J. D. and Edith Ferrin to the Snake River Land Company, Warranty Deed, March 22, 1928.

47. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 13, 1944; Jackson Hole Guide, December 2, 1965; Markham, "The Hatchet and Elk Ranches," Wyoming State Archives; Merritt Ferrin, "The Elk Ranch," transcript, acc. #1455, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; and interview with Ada Clark, #8.

48. Orin and Lorraine Bonney, "Shoot-out at the Cowboy Bar," Teton 14 (1981):12-13.

49. Jackson's Hole Courier, October 9, 1919.

50. Jackson's Hole Courier, April 16, 1914, and May 13, 1920.

51. Jackson Hole Platbook, Fabian Collection, Grand Teton National Park; Jackson's Hole Courier, August 1, 1929; Fabian Papers, RAC, Box 18, File 179, J. P. Ranch 1928-1930; Box 19, Files 180-181, J. P. Ranch 1930-1936; and Jackson's Hole Courier, October 27, 1927.

52. Homestead Patents: 710289, Charles Davis, 1918; and 1037836, Gerrit Hardeman, 1929; Teton County Records, Deed Record Book 2, p. 15, Charles and Helen Davis to Gerrit Hardeman, Warranty Deed, April 16, 1919; Deed Record Book 7, p. 275, Luther and L. M. Taylor to Gerrit and Alta L. Hardeman, Warranty Deed, April 26, 1943; interview with Lamar Crandall Hardeman by Jo Anne Byrd, #15, "Last of Old West Series;" Jackson's Hole Courier, June 26, 1924; and Jackson Hole News, December 21, 1972, and September 22, 1977.

53. Jackson's Hole Courier, August 23, 1951; and Jackson Hole Guide, November 1, 1973.

54. Jackson Hole Guide, July 10, 1986.

55. Jackson's Hole Courier, December 12, 1948; Superintendent's Monthly Report, June 1958, Grand Teton National Park, Box 743799, Federal Records Center, Denver, CO; Ethel Jump interview, transcript, Jackson Hole Historical Society and Museum; Struthers Burt, Diary, p. 41, and Natural Resources Management Plan, Grand Teton National Park, pp. 131-133.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

grte/hrs/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2004

—routed on the overhead

sign at the Cunningham Cabin in Grand Teton National Park. The first

Cunningham brand was the JP—

—routed on the overhead

sign at the Cunningham Cabin in Grand Teton National Park. The first

Cunningham brand was the JP—  —for the first and middle initials of John Pierce

Cunningham. However, the Cunninghams sold this brand, along with their

ranch and cattle, to J. P. "Pete" Nelson in 1909. The Cunninghams bought

back the ranch and brand in 1914. Four years later, the Cunninghams

acquired the Bar Flying U brand, when they bought the ranch and cattle

of James Uhl. Cunningham decided to drop his old JP brand in favor of

the Bar Flying U, because the former was too similar to Pete Nelson's

PN—

—for the first and middle initials of John Pierce

Cunningham. However, the Cunninghams sold this brand, along with their

ranch and cattle, to J. P. "Pete" Nelson in 1909. The Cunninghams bought

back the ranch and brand in 1914. Four years later, the Cunninghams

acquired the Bar Flying U brand, when they bought the ranch and cattle

of James Uhl. Cunningham decided to drop his old JP brand in favor of

the Bar Flying U, because the former was too similar to Pete Nelson's

PN—  —brand

and J. D. "Si" Ferrin's JF—

—brand

and J. D. "Si" Ferrin's JF—  —brand.

—brand.