|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

A Proposed Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway |

|

THE OPPORTUNITY

Over the years, as the concept of conservation developed in this country, preservation of rivers as such has received little attention. And now important opportunities are in most cases foreclosed. We have used, in some cases abused, and generally taken our rivers for granted.

In the last few years an interest in the preservation of free-flowing streams has begun to develop, but even in this movement the accent frequently has been on specialized river use such as running white water, float trips, and the like.

To date, no significant section of a major river is in public ownership for preservation purposes. Only, it seems, where man proposes to change the rivers drastically for a variety of water control purposes does he acquire control in the public interest. Grand Canyon National Park might appear to be an exception and is in a sense. But even there, the accent is not on the river, rather on the canyon.

The dynamics of present-day civilization add momentum to movements and programs which continue to impound, artificially regulate, or otherwise alter our rivers.

Here on the Upper Missouri, there is still an opportunity to preserve a significant stretch--an opportunity peculiarly suited to preservation and to telling the story of this river and its part in our history and our heritage in a setting little changed from the historic scene. By fortunate coincidence, it combines along with history an unusual variety of interests, scenic, geologic, wildlife, and withal a wonderful sense of wild, unspoiled nature.

NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE

The 180-mile stretch of the Missouri between Fort Benton and Fort Peck Reservoir in Montana is the last remaining significant and essentially undisturbed segment of this river--our longest, certainly one of our most important and, in fact, one of the major rivers of the world. On this factor alone, its national significance could probably stand. But further strongly augmenting this conclusion are its rich historical interests. The Missouri, and specifically this section of the Missouri, has important associations with the Lewis and Clark Expedition and with subsequent historical themes concerned with the westward expansion and development of this nation--the fur trade, the gold rush, Indian and military affairs, river navigation, and the colorful era of the river steamboat.

There are still other important attributes. This stretch of the Missouri contains what is probably the most striking scenery of its 2500 mile course--scenery which elicited glowing description by Lewis and Clark. Geologically, it tells an outstanding story including the unusually interesting epic of its disarranged drainage and the cutting of a new river course as a result of continental glaciation. Archeologically the area possesses a number of sites representing aboriginal culture of the Plains Indians. Paleontologically this story is still obscure but potentially and quite probably rich.

These important and unusually varied attributes in combination are judged to be clearly of national significance.

|

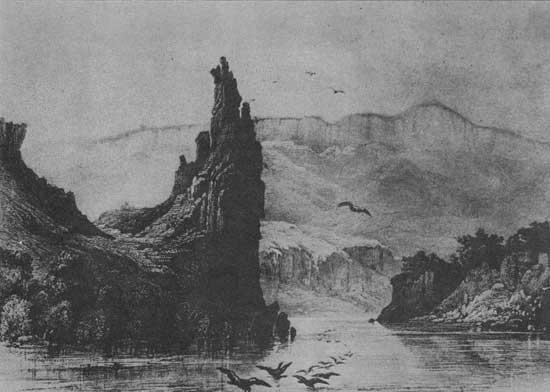

| Bodmer sketch 1833 |

". . . we came to a remarkable place where the Missouri seems to issue from a narrow opening, making a turn round a dark brown rugged pointed tower-like rock on the south, to which the traders have given the name of the Citadel Rock."-- Maximilian - 1833

|

| Bodmer's "Citadel Rock" - now Cathedral Rock - towers above the Missouri little changed since 1833. |

|

| Bodmer sketch 1833 |

". . .we saw, on the north bank, a jagged conical rock, which stands quite isolated on a hill covered with short grass. . . A herd of wild sheep looked down upon us from these heights."Maximilian - 1833

|

| National Park Service 1961 |

SUITABILITY

Fundamentally, this area is highly suited to preservation for public enjoyment. Most of it, and in fact all of the scenically outstanding portions are essentially unchanged from the time when Lewis and Clark first passed through here. The historic scene in other words has a high degree of integrity.

In several important respects, this area contains scenic, scientific, and historical categories or themes not now represented in the National Park System--an unspoiled section of one of our most important rivers, an example of river drainage disarranged by continental glaciation, fine representation of Upper Cretaceous geological strata, archeological sites such as buffalo jumps representing aboriginal culture of the Plains Indians, the Lewis and Clark river story to supplement and complement specific Lewis and Clark sites previously given national recognition, river navigation, and the steamboat era. These by their nature and in this setting represent a most interesting story readily adaptable to interpretation for public enjoyment.

Located off the beaten path as it is and because of its suitability for enjoyment by river use, supplemented by vehicular access at points along the rim, there is a very realistic possibility to maintain much of the wild and wilderness quality it now possesses.

The area is readily and adequately accessible by State and Federal highways and fortunately not smothered by a tight network of highly traveled roads.

FEASIBILITY

Preservation of this section of the Missouri River involves a number of feasibility considerations and the full picture is not yet clear.

The present pattern of land ownership does not appear to present unusual or severe problems. The fact that over 50 percent of the study area is in public ownership is potentially helpful.

Present land use is largely grazing supplemented by a small amount of irrigated cropping in the few stretches of wider bottomlands as in the Fort Benton-Virgelle Unit and at the Judith-Missouri River junction; and with the lower end administered as a game range. In the central and more scenic portion, the land is of relatively small economic value. This pattern of use appears to be susceptible to a formula of preservation which would allow continuation of existing intensive farming above Virgelle and of game management objectives in the game range.

The establishment, development, and management of an area under administration of the National Park Service for the preservation and enjoyment of the nationally significant values of this river would bring with it considerable economic benefit to the State and local communities. Its most important values, however, would unquestionably be in the enjoyment and inspiration of visitors--intangibles which cannot reasonably be measured in terms of economics.

Other potential uses for this stretch of the river and its immediate valley area presently being studied and hence cannot yet be weighed. These include primarily hydroelectric power and mineral resources.

A reservoir proposal would, of course, provide opportunities for diversified water-related recreation. While it unquestionably would get use, this sites does not lie in an area where there is significant need for such an outlet. The immediate population is sparse, while larger concentrations, such as at Great Falls to the west, are within easier reach of reservoirs upstream.

It is quite probable, that, as recommendations of the several public agencies involved become known, support for the different possibilities will be widely and sharply split.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

lewisandclark2/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jan-2008