|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

A Proposed Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway |

|

THE AREA

SCENIC FEATURES AND SETTING

The 180-mile reach of the Missouri River from Fort Benton to Fort Peck Lake divides itself geographically into three separate units--the Fort Benton-Virgelle Unit, the White Rocks-Badlands Unit, and the Fort Peck Game Range Unit. Each has its own distinctive characteristics, the readily accessible Fort Benton-Virgelle Unit being the least scenic and supporting the most man-made developments; the White Rocks-Badlands Unit being least accessible and having highly scenic and wilderness character; and the Fort Peck Game Range Unit with its broader valley and planned land use possessing the finest wildlife habitat.

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

Fort Benton - Virgelle Unit

Downstream from Fort Benton to the little community of Virgelle, a distance of 42 river miles, the stream course is dotted with picturesque islands and sandbars. The banks as viewed from the river extend upward several feet, and in most cases shield from view the rather extensively cultivated fields which extend to the bottom of the river bluffs. The bluffs as seen from the river are grass-covered and rise rather sharply from the flood plain to the flat prairie above.

Countless years of erosion by the Missouri River have cut into the earth, forming the present rather narrow flood plain of the river. The existing gullies and rugged hills which drop into the bottomland are impressive monuments to the erosive power of running water. Prior to settlement by white man, this country beyond the rim of the river valley was a vast grassland extending to the base of the Rocky Mountains. Today much of this Great Plains area has been plowed and planted in wheat. Such is the case with the high benchland flanking the stretch of the river between Fort Benton and the Judith River.

In the valley between Fort Benton and Virgelle are several man-made features such as the Great Northern Railroad grade, power and telephone lines, roads of various types, ranches, and the like. However, most of these features are not visible as one journeys on the river. The Missouri along this section averages 600 feet in width with a flood plain about one-half mile across. The bluffs rise approximately 300 feet above the river.

White Rocks - Badlands Unit

The scenery gradually changes downstream from Virgelle. Here the river has cut more deeply into its bed, and the flood plain narrows. Here, also, there is an almost complete lack of man-made features for about 45 miles downstream almost to the mouth of the Judith River. This is the spectacular White Rocks section of the Missouri. In this section, a most wonderful impression of wilderness prevails, and the landscape remains very much as it was when Lewis and Clark first saw it; only the big game animals such as bighorn sheep, elk, and buffalo mentioned so frequently in their journals are no longer there.

Soon after leaving Virgelle, almost imperceptible outcroppings of a glistening white sandstone appear. Progressively downstream, more and larger sections of this rock are seen. Nestled among these rocks in sharp picturesque contrast are scatterings of pine and juniper. The sandstone formations become more and more unusual in shape, size, and form, resembling ancient castles, parapets, and other seemingly architectural structures built by some giant hand. As subtle background to the dark evergreens and the white rocks are the muted greens and copper of the grass, the blue-gray sage, and the light green cottonwoods--all reflecting in the sometimes green, sometimes brown of the Missouri. Frequently seen are outcroppings of a dark intrusive rock which has been thrust upward through the white sandstone forming huge structures which in places have the appearance of man-made walls of rectangular blocks. In several instances, formations of this same dark rock rise up sharply like sentinels standing guard over the river. The Missouri is narrowest, slightly over 300 feet, at one of these--Cathedral Rock. Other impressions are of some giant prehistoric animal whose jagged backbone begins high up on one side of the breaks, plunges out of sight into the river bed, then emerges and continues upward on the other side until it disappears over the rim.

As one journeys along the river, rapids are encountered where these darker, harder rocks cross the stream bed. Although not as turbulent as the white waters of the Colorado River in Grand Canyon or the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument, these rapids offer an exhilarating experience to the boater at certain times of the year.

This reach of the river appeared equally impressive to those who were fortunate enough to observe it in the past. Captain Lewis described this area thus in 1805:

"These hills and river-cliffs exhibit a most extraordinary and romantic appearance. They rise in most places nearly perpendicular from the water, to the height of between 200 and 300 feet, and are formed of very white sandstone, so soft as to yield readily to the impression of water, in the upper part of which lie imbedded two or three thin horizontal strata of white freestone, insensible to the rain; on the top is a dark rich loam which forms a gradually ascending plain, from a mile to a mile and half in extent, when the hills again rise abruptly to the height of about 300 feet more. In trickling down the cliffs, the water has worn the soft sandstone into a thousand grotesque figures, among which, with a little fancy, may be discerned elegant ranges of freestone buildings, with columns variously sculptured, and supporting long and elegant galleries, while the parapets are adorned with statuary. On a nearer approach they represent every form of elegant ruins--columns, some with pedestals and capitals entire, others mutilated and prostrate, and some rising pyramidally over each other till they terminate in a sharp point. These are varied by niches, alcoves, and the customary appearances of desolated magnificence."

|

| Karl Bodmer - 1833 |

"In the midst of this fantastic scenery are vast ranges of wall, which seem the productions of art, so regular is the workmanship."Lewis and Clark Journals - 1805

|

| National Park Service - 1961 |

|

|

Narrow dikes of dark rock dominate the scene like the jagged backbone of

a huge prehistoric reptile.

|

|

| Relatively unchanged are the "Stone Walls" and narrow confines of the Missouri which so impressed Lewis and Clark in 1805. |

Nearing the Judith River, the canyon widens somewhat. The white rocks pass from view and the bluffs take on a grayish color. Denser concentrations of evergreens are found at different elevations along the bluffs.

At its confluence with the Judith River, the valley is substantially wider on both sides of the Missouri and supports about five ranches. Here are the historic sites of Forts Claggett and Chardon, and Camp Cooke. Here, too, is the PN Ferry, the nearest crossing of the Missouri downstream from the Virgelle Ferry. Large cottonwood, ash, and boxelder line portions of the banks, and the mouth of the Judith Valley as viewed from the Missouri River is thickly wooded. The largest concentration of deciduous trees--predominantly cottonwoods--along the entire 180-mile length, is in this vicinity.

From the Judith River Valley to Cow Creek the scene is one of rugged Badlands in various shades of gray, brown and yellow. In places, these massive products of erosion rise to heights of 1,100 feet above the river. The rapids along this section are generally swifter and more exciting than those upstream.

Lewis and Clark had this to say about the Badlands in 1805:

". . .The river has become very rapid, with a very perceptible descent. Its general width is about 200 yards,...The water is bordered by high rugged bluffs, composed of irregular but horizontal strata of yellow and brown or black clay, brown and yellowish-white sand, soft yellowish-white sandstone, and hard dark brown freestone; also, large round kidney-formed irregular separate masses of a hard black iron-stone, imbedded in the clay and sand; some coal or carbonated wood also makes its appearance in the cliffs, as do its usual attendants, the pumice-stone and burnt earth...the country is,...rugged and barren...the only growth of the hills being a few pine, spruce, and dwarf cedar, interspersed with an occasional contrast, once in the course of some miles, of several acres of level ground, which supply a scanty subsistence for a few little cottonwoods... The only animals we have observed are the elk, the bighorn, and the hare common in this country...."

Maximilian, Prince of Wied, observed the Badlands while on his keel boat excursion up the Missouri in 1833. He described them as follows:

"...The mountains here presented a rude wilderness, looking in part like a picture of destruction; large blocks of sand-stone lay scattered around....We saw most singular summits on the hills. Entire rows of extraordinary forms joined each other, and in the lateral valleys we had interesting glimpses of this remarkable scenery, as we were now approaching the most interesting part of the Mauvaises Terres [Badlands]...here they begin to be more continuous, with rough tops, isolated pillars, bearing flat slabs, or balls, resembling mountain-castles, fortresses, and the like, and they are more steep and naked at every step.... Many strata are inclined at an angle of 30° to 60°, and others perfectly horizontal.... A few pines and junipers appear here and there, and on the declivites small patches of grass...but the naked rude character of the Mauvaises Terres seems to be unique in its kind, and this impression is strengthened when you look up and down the river...."

|

|

THE BADLANDS

"No portion of the Upper Missouri country exhibits the

effects of erosion and denudation on so large a scale...

and the variegated strata add to the picturesque effect

of the scenery,..."

-- F. V. Hayden - 1859

|

Little change has taken place in the Badlands since the days of Lewis and Clark, and Maximilian, and with the exception of the elk and bighorn sheep mentioned by Lewis and Clark, the descriptions given by these men in 1805 and 1833 hold true today.

Downstream from Cow Island to the western boundary of the Fort Peck Game Range the topography is a transition from the rugged badlands to a more open character, with wider flood plain and lower bluffs. Here, there is more vegetation on the islands and along the banks. Wildlife sightings are more frequent, especially of deer.

Evergreens along the bluffs in the vicinity of Cow Island--predominantly ponderosa pine--grow in the thickest stands found along the entire 180-mile river stretch.

Fort Peck Game Range Unit

The topography along the river from the western boundary of the Fort Peck Game Range to Ryan Island, a distance of 39 miles, becomes still more open. The river meanders in its flood plain which in places is over a mile wide and the river has not cut into the plains so deeply as in the Badlands. More islands are present, some covered with large groves of cottonwood and some with shrub willow and wild rose, among which can be observed numerous deer. This section of the river more than any other provides the best habitat for wildlife such as geese, ducks, beaver, and deer.

The stretch of river bottom beginning at Ryan Island and extending upstream about 25 miles is subject to flooding for short periods. Fort Peck Reservoir is expected to back up the full 25 miles to elevation 2,250 once in a hundred years. During the flood of 1948 this almost happened. Water backed up to elevation 2,245 killing some of the trees and shrubs. However, by 1961 the vegetation had re-established itself and the scene as viewed from the river now has a natural appearance.

There are a few irrigated fields planted predominantly in cereal and forage crops for wildlife. In most cases, these fields are not visible from the river.

Natural bridges on the canyon rim add variety to the scene.

GEOLOGY

The area under study has much to offer visitors interested in geology. The landscape has been carved from an interesting series of sedimentary rocks of Upper Cretaceous Age, far better displayed here than in any unit of the National Park System. The story of the present Missouri River is interesting, and an important chapter in the area's geology.

No one knows when the original Missouri began, but it is generally agreed among geologists that before the Ice Age (which began about a million years ago), it, and such other streams as the Yellowstone and Little Missouri River, flowed northward into the Lake Winnipeg depression and ultimately to the Hudson Bay region.

During the Ice Age, great continental glaciers formed in Canada and invaded what is now the United States on four different occasions. The most recent glacial advance was during what is called the Wisconsin stage, a period which ended only some ten thousand years ago in the northern Great Plains. This is very recent, geologically, but is well borne out by numerous Carbon 14 age determinations in a number of sites in nearby states. This last advance of the ice sheet blocked the former drainage of the Missouri and forced it into what is generally its present course. Evidence for this southward diversion of the Missouri includes a number of abandoned channels, one of which is presently used by the Milk River some 60 miles north of the area under study. The general story of these changes in flow of one of America's major streams is important in understanding the area's geological development.

The canyon of the Missouri River Breaks is of recent origin, having been cut by the Missouri in the past 10,000 years, or so, after retreat of the continental glacier. Thus the slopes are steep, the channel is well below general elevation of the plains on either side, and the river is actively eroding its channel deeper at several places in the Breaks area.

The geological structure of this area is simple. The rocks are generally flat-lying, but many local thrust faults bring one formation up against another. The Missouri River roughly parallels many of these faults between Virgelle and the confluence of Arrow River. East of the Judith River, however, most of the faults are transverse to the stream. Many of these thrust faults are closely spaced together and seem related to the curious faulting in the Bearpaw Mountains to the north where slippage of large rock splinters occurred along a bed of bentonite in the Colorado shales. These peculiar examples of faulting are quite unusual and are worthy of special attention in any interpretive program for this area.

Numerous plugs, stocks, and dikes of Tertiary intrusive rocks are conspicuous along parts of the river route. These are associated with igneous intrusions in the Bearpaw Mountains some 35 miles northward. More rapid erosion of softer enclosing rocks has left these intrusive bodies standing sheer and gaunt, resembling great walls or towers. They contribute much to the scenic quality of the landscape.

|

|

National Park Service 1961

|

"In several places where the sand-stone summit appeared plainly to represent an ancient knight's castle, another remarkable rock was seen to traverse the mountain in narrow perpendicular strata, like regularly built walls... of a blackish-brown rock... They run in a perfectly straight line from the summits of the mountain to the foot... "-- Maximilian - 1833

|

| Bodmer sketch - 1833 |

The river flows through a fine section of generally horizontal sedimentary layers of Upper Cretaceous Age. In floating down the river one crosses progressively younger beds of this series, covering ten million years or more of time. During the Upper Cretaceous Age (roughly between 70 and 80 million years ago), most of the present Great Plains and midwest sections of the United States were beneath the waters of a great inland sea. For a time 50 percent of North America was flooded. Vast areas in South Dakota, Nebraska and eastern Colorado are covered by the Pierre shale and other strata deposited by this tremendous extension of the ocean.

But this sea didn't cover the Missouri Breaks country throughout all this period. On the contrary, now and then during Upper Cretaceous time, this area had seashore conditions with deltas and coastal plain deposits being laid down. The non-marine strata along the Missouri here are samples of a widespread series of sandy deposits dropped by ancient rivers. These streams (of which there are no traces today) drained an ancient landmass (called the Mesocordilleran Geanticline) which rose high and underwent intense erosion a few hundred miles to the west.

Several of the local rock layers described below are of continental origin and can be visualized as great wedges of non-marine rock deposits, very thick to the west of this area. To the east and south, they thin out and interfinger with marine shales and limestones which were deposited in the Cretaceous sea. Because the margin of the sea moved back and forth as the sea expanded and contracted over millions of years, these varied rock layers--some marine, with sea-animal fossils; others land deposits with coal and dinosaur fossils--represent a rather complete record of changing ancient geographical conditions.

Different rock formations in the study area will be described below in order of their appearance during a hypothetical river trip from Fort Benton to the upper end of the Fort Peck Reservoir.

For the first few miles down the river from Fort Benton to Virgelle, the river traveler passes low bluffs of thick marine shale of the Colorado Group. These beds represent a great flooding by the sea and are exposed across a vast expanse of territory west of here, extending almost to the Rocky Mountains and northward into Canada. They also are widespread to the south in Wyoming, South Dakota, eastern Colorado, Nebraska, and western Kansas.

At Virgelle, and for 15 miles downstream, the rocks of the Colorado Group lie beneath the surface except where thrust up along faults, and the overlying white Eagle sandstone makes up the canyon walls. The latter formation represents a shoreline depositional phase, having no marine fossils, but with a few thin coal veins and scattered plant fossils.

Dark colored rock sentinels stand today as crumbling relics of powerful subterranean forces which pushed hot liquid rock up through the earth's surface.

From about 15 miles below Virgelle, the soft shales of the Colorado Group, which have been upthrusted along faults, form gently sloping valley walls to the confluence of Arrow Creek. Low cliffs of the Eagle sandstone rise a mile or so back from the river banks although in places the sandstone impinges against the river. In this stretch, conspicuous stocks and plugs, such as Eagle Buttes, and numerous dikes all of Tertiary volcanic rock, rise above the surrounding sedimentary strata and add variety to the scenery.

Below the confluence of Arrow Creek, exposures of Claggett shale become conspicuous, especially south of the river, and continue to crop out for more than ten miles downstream from the mouth of the Judith River. Mostly a dark, marine shale, roughly equivalent to the lower Pierre shale of areas to east and south, it represents another advance of the ancient sea. Bentonite beds near its base are evidences of volcanic activity far to the west, and of great windstorms which dropped much volcanic ash into the waters of this ancient sea.

In the same stretch of river, the overlying Judith River formation, mostly sandstone, forms impressive cliffs and picturesque rock pillars. Its base is shaly (with lignite beds) facilitating cliff formation by sapping and by landsliding of the Claggett shale beneath. Of continental origin, the Judith River formation represents a period when deltas and expanding coastal plains "pushed" the sea eastward. (Actually, no doubt, the sea retreated because of such other causes as coastal uplift thereby permitting heavy shoreline deposition.)

The last 15 miles of the riverway route pass through a much faulted area, which exhibits long wedges of these sediments (10 to 15 miles north east - southwest, but only one-half to three-fourths miles east - west). Most of these fault thrust plates are of the Judith River formation. Here, too, the Bearpaw shale with its numerous concretions and bentonite beds is exposed. This shale is marine, corresponding to the upper part of the Pierre shale to east and south; it represents one of the last great expansions of the Upper Cretaceous sea.

Paleontological interpretive values are little known. The continental beds might well be found to contain fossils of such dinosaurs as Ornithomimus and Trachodon, and possibly fragmentary remains of very primitive mammals. They are also possible bearers of quantities of fossil plants. It was this period which witnessed the rise of modern plants (angiosperms), and the decline and fall of the dinosaurs. If rich sites were to be discovered, a gap in present National Park Service paleontological coverage would be filled.

The marine beds (Claggett shale and Bearpaw shale) might be found to yield such typical fossils of this period as sea-going reptiles (mososaurs and plesiosaurs); such conspicuous invertebrates as ammonites and baculites are known to be locally abundant.

"Among the cliffs we found a species of pine (limber pine) which we had not yet seen..."Lewis and Clark Journals - 1805

VEGETATION

This area lies in the Prairie Biome, more specifically the Mixed Prairie, which is composed predominantly of mid and short grasses. It is part of one of the largest grasslands in the world--the Great Plains--which extend from Canada southward to Texas, and from the Rocky Mountains eastward to the True Prairie where tall and mid grasses predominate. The vegetation is varied, however, with representation of woody plants on the broken slopes and river bottoms.

Overall, it is typically semi-arid, with the erosional pattern providing what suitable habitat there is for woody growth. Scenically, grasses and forbs predominate. Trees and shrubs play a lesser role, though are complementary to this scene, and serve as scattered accents to the eroded bluffs and canyons, the striking rock formations, and the river itself.

Trees. The native trees found here are ponderosa pine, limber pine, Douglas fir, Rocky Mountain juniper, cottonwood, ash, willow, and box-elder. The conifers grow predominantly on the bluffs, while the deciduous types are found along the river banks and on islands.

Shrubs. The predominant shrubs are greasewood, shrub willow, wild rose, squawbush, snowberry, rabbitbrush, shadscale-saltbush, and various types of sagebrush.

Grasses. The more common grasses are buffalo, blue grama, western wheatgrass, Junegrass, needlegrass, and prairie sandreed.

WILDLIFE

When Lewis and Clark pushed through this wilderness, they described frequent sightings of buffalo, elk, deer, antelope, bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, wolf, coyote, muskrat, beaver, and prairie dog.

Of these, the buffalo, elk, bighorn sheep, grizzly bear, and wolf were once eliminated from the scene. Recently, however, elk and bighorn sheep have been reintroduced into the Fort Peck Game Range, which together with the stretch as far west as Cow Creek appears to be the best habitat for wildlife.

Lewis and Clark were impressed also by the birdlife seen here. Their observations included among others the eagle, grouse, curlew, whippoorwill, kingbird, swallow, Rocky Mountain bluebird, and many species of waterfowl.

Today this area is richly endowed with birdlife. Predators such as hawks, owls, and eagles are numerous, especially along the river. The Central Flyway, one of the four main migratory routes for waterfowl in the country, crosses the Missouri here. Geese and ducks are numerous, particularly in the Fort Peck Game Range where the habitat has been improved by planned methods. Songbirds of many types break the stillness with their calls. Birds of the prairie and the river both inhabit this region of the Missouri. Native upland game such as sage and sharptailed grouse are present beyond the bluffs, as are introductions of pheasant and partridge. It is a birdwatcher's paradise.

|

|

"Saw a vast number of buffalo feeding in every direction around us in

the plains, others coming down in large herds to water at the river,..."

-- Meriwether Lewis - 1805

|

Lewis and Clark observed many types of fishes including Missouri herring, whitefish, trout, shovel-nosed sturgeon and catfish. Today, yellow perch, goldeye, sauger, burbot, channel catfish, sucker and carp are the principal fishes. Others, such as trout, crappie, drum and bullhead are found in Fort Peck Lake and may be taken from the upper end of the lake which lies in the Fort Peck Game Range Unit.

ARCHEOLOGY

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, the Upper Missouri country appears to have been a no man's land frequented by many groups of Indians, but definitely held by none. Pushing down from the north were the Blackfeet, Sarsi, Atsina and Assiniboine, while from the south the Crow, groups of Shoshone, and tribes of the Sioux vied for entrance into the area. Also the Kutenai and Flathead tribes, who at the time of first contact by whites lived west of the Rocky Mountains, may have been common visitors here. With the acquisition of guns and horses and about the time of the establishment of the first trading posts, the Blackfeet had consolidated the region into their territory. The historical evidence thus leaves an open question as to the number and variety of cultural groups that may have once been found in this region.

During the summer of 1962 an intensive survey of the archeological potential of this Upper Missouri region was made by the Smithsonian Institution. To date no full-scale excavations have been conducted in the region, so no statement of cultural relationships can be made and only a brief summary of the sites found and of their potential value to the interpretations of the prehistory of the northwestern plains is possible at this time.

In addition to the historic sites, summarized elsewhere in this report three site types are found in the region: open camp, burial, and bison kill. The open camp type falls into two distinctive sub-groups based on the presence or absence of tipi rings. Aside from tipi rings all camp sites were similar in nature except one site which was stratified. They grade in size from tiny camps one-half acre or less to large camps covering thirty or more acres, but most are small, reaching no more than two acres in size.

Of the forty-one camps located, twenty were marked by the presence of tipi rings. The predominant style of tipi ring is a single circle of stones ranging in diameter from 7 to 21 feet, with a median diameter of 9 to 12 feet. At a few of the sites, tipi rings composed of two concentric circles of stones occurred. These double rings were always in the minority and of large size, ranging from 18 to 20 feet in diameter.

Three localities deserve special mention because of the size and number of camp sites found in them.

The first locality is found on both banks of the Missouri close to the mouth of the Little Sandy Coulee. On the north bank, west of the confluence of the river and the coulee, is a large tipi ring site designated 24CH211. This site covers about thirty acres and extends as a narrow band along the valley rim for about one-half mile. The major features of this site are thirty-one complete tipi rings, about as many more partial rings, and two dozen small rock mounds of unknown use.

East of site 24CH211, across the Little Sandy Coulee, are two small tipi ring sites, 24CH218 and 24CH219. There are four complete tipi rings at 24CH218, one of them the double ring variety. The historic use of site 24CH219 is suggested by a well-preserved hide scraper made from a rifle barrel collected near one of the two tipi rings found there.

On the south side of the river directly across from the Little Sandy Coulee are three tipi ring sites of medium size and a stratified site covered with four feet of over-burden. The three tipi ring sites, 24CH221, 24CH222, and 24CH223, of ten to fifteen acres each, form an almost continuous series, running for one and a half miles along the valley rim. The stratified site, 24CH220, lies in the river bottom where high water erosion has exposed two and possibly three cultural strata. The two principal cultural zones are composed of bone with a light admixture of charcoal. A fire pit suggests the possibility of a third occupational zone, but excavation would be needed to determine its associations.

The second locality is on the river bottom east of the mouth of Arrow Creek. Here is found a single large tipi ring site covering twenty-five or more acres. This may be the location of the Gros Ventre camp noted by Maximilian in 1833.

The third locality is around the mouth of the Judith River. On the south side of the Missouri River and the west side of the Judith, about a quarter of a mile south of Camp Cooke (24FR204) is a moderate sized camp site with scattered cultural deposits. On the east side of the Judith there is another open camp site and on the north side of the Missouri are five more. The largest of these sites is 24CH231 which covers approximately forty acres. Test excavations reveal cultural deposits to a depth of three feet. On the southern edge of this site are what is believed to be the remains of Fort Chardon.

The remaining five sites, 24FR203, 24CH229, 24CH230, 24CH232, and 24CH233 are smaller than 24CH231 but nevertheless are good potential sources of information on the prehistory of the area.

Only two burial sites were located: one site, 24CH202, lies on the north side of the Missouri about four miles west of the town of Virgelle and the other, 24CH209, is at the western end of Brule Bottom overlooking the site of Fort McKenzie. The one established burial mound at site 24CH202 has been completely destroyed by amateur diggers, however, excavation of the several cairns on the site might reveal further burials. In addition to the cairns a number of tipi rings are also found. Burial site 24CH209 is situated on a small flat about 150 feet above the present river level. At least some of the burials are of the historic period since numerous glass trade beads and fragments of a clay pipe were collected from the surface of two of the cairns.

|

| Arheological sites of the proposed Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway, Montana. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Sites 24CH210, 24CH234, and 24CH240 are bison kills. Site 24CH234 is about ten miles southeast of Fort Benton. The site shows the possibility of high artifact yield and, as revealed by a bulldozer cut, has five or more distinct strata. Site 24CH210 is about five miles west of the Virgelle ferry on the south side of the river. The actual jump area was not located, but a maze of rock lines remain which, with careful mapping, might reveal the original plan. Site 24CH240 is the bison jump described in the Lewis and Clark journals for May 29, 1805, however, the ravages of the river have removed most of the deposit. Only a few tiny fragments of bone remain of the large mound of bison carcasses described by the explorers.

Since the majority of the camp sites are small and have sparse cultural materials associated with them, it would appear that the prehistoric occupants of the Upper Missouri were nomadic bands of hunters and gatherers who were poor in material goods. This is further evidenced by the lack of any indication of horticulture or of village type dwellings. Also evidence of exploitation of the river resources was not found.

Only two sites, 24CH220 and 24CH231, from cursory examination, suggested more than moderate antiquity. A more exhaustive study is needed before a definitive statement of the cultural developments within the region can be attempted. However, investigations thus far have shown most of the existing sites to be representative of aboriginal culture of the Plains Indians.

HISTORY

The Missouri River between Fort Benton and the Fort Peck Reservoir has outstanding historical interest because it is the last important section of the Missouri River where major aspects of its history can be commemorated in their original unspoiled setting. There are four major historical elements in American history represented here--the Lewis and Clark expedition, the early western fur trade, military and Indian affairs, and the era of Upper Missouri River steamboat navigation.

While it is true that the Lewis and Clark journey covered several thousand wilderness miles, it was the Missouri River and its headwaters which were the key to the success of this exploration, and it would be unfortunate if a major section of the Missouri River encompassing their explorations could not be preserved for posterity. From Fort Benton to Three Forks, the Missouri is characterized by several dams and intense bottomland cultivation. From Fort Peck Reservoir down to St. Louis the river has been engineered with channel pilings, flood walls, and big dams impounding reservoirs which have drowned out much of the original scene. Roads and bridges, industry, agriculture, and modern towns and cities have also left their mark. Only that portion of the Missouri River between Fort Benton and Fort Peck Reservoir--about seven and one-half percent of its total length--retains its primitive historic appearance.

Lewis and Clark were in this area approximately from May 23 to June 12, 1805, and much more briefly on their return journey in 1806. Here can be identified 14 unspoiled original Lewis and Clark campsites and most of the topographic and natural features which commanded their great admiration. The journals tell of back-breaking toil in ascending the Missouri at spring flood in canoes or pirogues, with locomotion variously provided by towline, sail, and oars. The explorers and their pirogues have passed on, but the magnificent setting portrayed in their journals remains in much of its detail. The meadows, canyon walls, and landmarks remain. The vegetation and much of the native animal life are the same. Only the bison, grizzly bear, and wolf are now missing.

Every bend in the river contains features which are reminders of incidents on the great journey of discovery. Turtle Creek marks the point where on May 26, 1805, Captain Lewis ascended the highlands and first caught a distant view of the Rocky Mountains, "the object of all our hopes and the reward of all our ambition." Dog Creek was originally called by the explorers Bull Creek because a buffalo went berserk through their camp, nearly causing disaster.

Arrow Creek was called by them Slaughter Creek because they found near there the remains of hundreds of bison which had been trapped by Indians when stampeded over a cliff, or "buffalo jump."

The Judith River was named by Captain Clark for a childhood sweetheart who would later become his bride and bear him several children. It was first called by them the Big Horn River. One of the most spectacular camps of the expedition was on Eagle Creek, which is centrally located in the marvelous canyon area now called the White Rocks of the Missouri, but known to Lewis and Clark as the Stone Walls. The explorers commented enthusiastically on the striking geologic forms here which they likened to grotesque animal figures, sculptured columns and galleries, the ruins and desolated magnificence of ancient cities, in all, a scene of "visionary enchantment."

The Marias River was named for a cousin of Meriwether Lewis, Maria Wood, for whom he had conceived a romantic attachment. At the mouth of the Marias was one of the most significant encampments. The Captains remained here for over one week in early June in order to resolve a dilemma as to which was the principal stream to be followed, and they explored a considerable distance up the Marias before coming to the decision that the Missouri River was the main channel which would lead them to their transcontinental goal. From here, they passed on to make their detour of the Great Falls and their fateful meeting with Shoshone Indians above the Three Forks. While no Indians were seen by the explorers in the Missouri River Breaks country, they did find the fresh remains of large Indian encampments, particularly in the neighborhood of the Judith and the Marias.

|

| Fort McKenzie attacked by Indians August 28, 1833. Sketch by Bodmer. |

For many years after Lewis and Clark returned to St. Louis, the Upper Missouri River was substantially closed to fur traders by Blackfeet hostilities, the nearest approach being the Yellowstone River at the mouth of which was built Fort Union in 1828. The Missouri Breaks country was first successfully penetrated in 1831 when emissaries from Fort Union managed to establish contact with a branch of the Blackfeet nation called Piegan, and a trading post called Fort Piegan, also known as Fort McKenzie, was established at the confluence of the Marias and the Missouri. After the first season, this original fort was destroyed and subsequently a second Fort McKenzie was built on Brule Bottoms. This flourished until 1843, when hostilities were renewed and the trader Chardon withdrew to establish a short-lived post opposite the mouth of the Judith River. The brief, but violent, era of the Missouri fur trade in this area is commemorated by several names which have survived, such as Gardipee Bottoms, Kipp's Rapids, and Dauphin Rapids. The latter name is a reminder of the visit in 1833 by Prince Maximilian and his retinue from Fort Union to Fort McKenzie. Karl Bodmer, artist in the employ of Maximilian, has left sketches of Fort McKenzie and Missouri River scenery which are of priceless historic value.

The flatlands opposite the mouth of the Judith River were the setting of two important Indian peace councils during the waning days of the fur trade. In 1846 the famous Catholic missionary, Father De Smet, and a band of Flathead Indians had a meeting here with the Blackfeet. In 1855 there was a large Indian treaty council here, engineered by Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens. At that time 3,500 Indians assembled here, including representatives of the Blackfeet, Nez Perce, and Flathead nations. As a result of this treaty the Blackfeet ceased their incessant and bloody raids, and met their former enemies on friendly terms upon the common hunting grounds. Also, the treaty cleared the way for large white settlements which were soon to spring up on the headwaters of the Missouri.

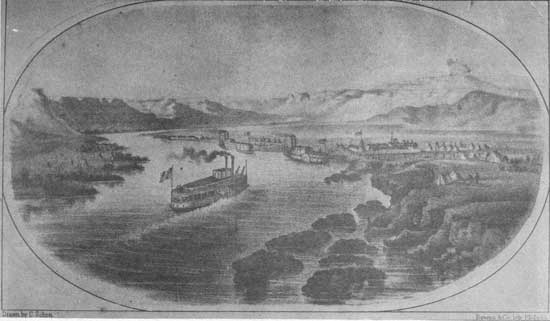

The first steamboat arrived at Fort Union in 1832 but the Missouri River above that point was considered unnavigable until 1859, when the steamboat Chippewa reached Brule Bottoms. Here in 1865 workmen attempting to establish the townsite of Ophir were massacred by Blackfeet.

The discovery of gold near Bannack City and Virginia City in the early 1860's started a great gold rush to Montana, and the Missouri River then became a major transportation route, with the amazing shallow-draft paddle wheel steamboat the principal mode of travel.

Fort Benton was established by Alexander Culbertson of the American Fur Company in 1846, later becoming a military post and Indian Agency. The first steamer arrived at this ultimate point of Missouri River navigation in 1860. In the peak year of 1869 there were 39 steamboat arrivals. For a time Fort Benton was the commercial capitol of Montana, with wagons radiating to the interior mountain towns. The old river bank where the steamers were once tied up still remains and much of the city in its heyday is admirably preserved. Only fragments of the adobe walls of the original Fort Benton survive, but the surviving picturesque town has now achieved distinction as a Registered National Historic Landmark.

|

|

Fort Benton was a link between the East and the West, a hub of

transportation, feeding men and supplies to and from the river,

and thus abetting the settlement of the land beyond.

|

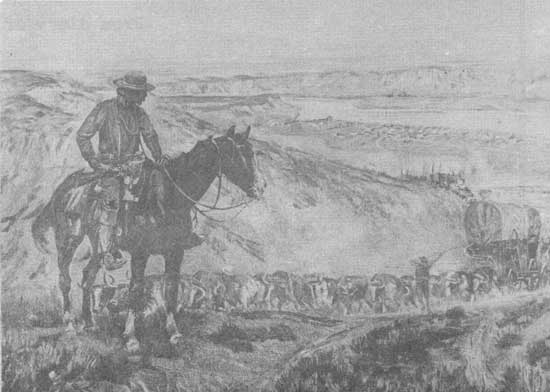

|

|

The wagon boss takes a final look at Fort Benton as his ox-drawn freighters climb the

Missouri River bluffs laden with supplies for the settlements beyond.

Painting by Charles M. Russell

|

|

|

CAMP COOKE. Sketch by A. E. Noyes - 1868

"...situated on the south side of the Mo. river... where the

Judith flows into the Mo....this fort is built.. with bastions, stockade moat, etc...."

-- From diary of Sarah E. Canfield, 1867

|

|

| Historic and Natural Features of the proposed Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway, Montana (click on image for a PDF version) |

Timber from the river bottoms was the principal fuel for steamboats. Several adventurers made a precarious living by supplying wood for the voracious steamers, which required up to 25 cords of such fuel a day. Wood Hawk Creek is a reminder. Coal Banks Landing commemorates a futile effort to use native coal in the steamboat furnaces.

Many of the major geologic features of the canyons, such as LeBarge Rock, Steamboat Rock, and Hole-in-the-Wall, are reminiscent nomenclature of steamboat days, as are Pablo Rapids, Deadman Rapids, Gallatin Rapids, and Iron City Islands. There is record of at least two steamboat disasters--the Marion and the Peter Belen--in this section of the river, while many other ungainly paddle-wheelers were stranded for weeks on treacherous riffles or sandbars. However, the enormous profits to be gained by a successful passage justified the dangers, and many fortunes were made. Ingenious methods of moving steamboats over shallows were devised and the pilot houses were sheathed in boiler plate to frustrate attacking Indians.

It was during the steamboat era that the Indian wars had an impact on this section of Montana. In 1866 the Army established Camp Cooke at the mouth of Judith River. It was built of logs in classic quadrangular pattern. This turned out to be a rather unhappy location for a post. The soldiers' morale suffered from dismal conditions, emphasized by Indian raids which the soldiers seemed powerless to prevent. The fort was abandoned in 1870, but the nearby Fort Claggett trading post, operated by T. C. Powers and Company, continued in operation for a few years longer. A large stone building which serves as a barn at the modern PN Ranch was built here in 1880 as a warehouse for Judith Landing.

Cow Island, named by Lewis and Clark because of buffalo in that vicinity, has a double distinction. It was the head of navigation for many steamers that did not dare attempt the further run to Fort Benton, and it became a depot for supplies and the head of a freight road to the upper country. In 1877 the Nez Perce Indians, while retreating from the U. S. Army after the Battle of the Big Hole, and before their defeat at the Battle of the Bear Paw, crossed the Missouri River at Cow Island, seizing supplies and attacking troops stationed there.

PRESENT PATTERN OF USE

The section of the Missouri River under study is developed very little. Developments which do exist occur mainly in three portions of the area: (1) the Fort Benton-Virgelle Unit, (2) the flood plain at the confluence of the Judith River within the White Rocks-Badlands Unit, and (3) the area from the vicinity of Robinson Bridge to Fort Peck Lake within the Fort Peck Game Range Unit. Other portions of the study area remain in fairly primitive condition, little changed by man, except through cattle grazing which is the principal land-use activity.

The principal recreation uses consist of hunting, fishing, and sightseeing trips. Hunting is excellent in the Fort Peck Game Range Unit and should increase in popularity and use in the future. Fishing is popular locally at the more accessible points along the river. Each June the Fort Peck Yacht Club, under the co-sponsorship of the Montana Chamber of Commerce, enthusiastically participates in a river excursion from Fort Benton to Fort Peck. The potential river use was pointed out by Mr. A. B. Guthrie in a November 1952 issue of the Saturday Evening Post entitled "The Badlands Are Still Bad." Albert and Jane Salisbury, in their book Two Captains West on the Lewis and Clark Expedition published in 1950, were very excited about a portion of the White Rocks area which they were able to reach by car.

From the Fort Benton bridge (above) to the Robinson bridge (below) lies a 150-mile stretch of the Missouri River crossed only by ferry.

As the reputation of this stretch has spread in recent years, more and more people have enjoyed boating here. Most trips begin at any of several good launching locations between Fort Benton and Virgelle, and end at the Robinson Bridge.

The existing developments and uses of the land in the three separate units of the study area are discussed as follows.

Fort Benton - Virgelle Unit

The section most disturbed by man-made features lies between Fort Benton and Virgelle where irrigated fields and cattle ranches exist in the river bottoms. Also along portions of this stretch are the Great Northern Railroad, U. S. Highway 87, county roads, utility lines, the small villages of Loma and Virgelle and their ferry crossings. Most of these are screened from the river by trees and bushes along the shore and by the immediate banks of the stream. The prairie beyond the bluffs along this stretch and as far east as the Judith River is quite extensively cultivated, the primary crop being wheat. However, these cultivated areas are not visible from the river and lie outside our study area. Practically all this unit is privately-owned.

White Rocks - Badlands Unit

The portion of the river and its bluffs from Virgelle to the Judith River is practically void of development, the exceptions being a very few unimproved roads and isolated ranchhouses, mostly abandoned. This contains the very scenic White Rocks section, which remains in a quite primitive condition.

In the valley at the confluence of the Judith River are a few ranches, some cultivated land, and a primitive campground. Here, too is located the PN Ferry and its county approach roads.

The Badlands section of the Missouri which extends from vthe Judith River east to the Fort Peck Game Range contains very little development. Existing developments consist of the Jensen and Power Plant Ferries and dwellings for their operators, the ferry approach roads, and a few ranch buildings, mostly deserted and dilapidated. Beyond the top of the river bluffs lies virgin grassland, for the most part, which seems to extend to the horizon where prairie and sky meet as one. This prairie land and those portions of the bluffs which are not too steep are grazed primarily by cattle. However, the range quality of the Badlands is poor and little used. In some places, livestock can get down to the river and have overgrazed the bottomlands.

Between Fort Benton and Virgelle the river is flanked by farmland and man-made features, but from the surface of the water these are generally masked from view by the river embanknents and their vegetative cover. The course of the river and its immediate banks are relatively undisturbed and will remain so if properly zoned.

The Virgelle Ferry (above) is a beginning point for those who wish the wilderness experience of penetrating by boat the spectacular White Rocks section of the Missouri. The Jensen Ferry (below) offers the motorist an opportunity to see the unique Badlands stretch of the waterway. A ferry crossing itself is a rare experience for many.

The portion of this unit from Virgelle to the Judith River is mostly state and privately-owned. This includes the White Rocks area. The portion from the Judith River to the end of this unit which includes the Badlands is primarily Federally-owned and administered by the Bureau of Land Management.

Fort Peck Game Range Unit

This unit of the study area extends approximately from the western boundary of the Fort Peck Game Range to Ryan Island, about 39 river miles downstream. All but a few acres is owned by the Federal Government and administered jointly through cooperative agreement between the Department of the Army and the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, Fish and Wildlife Service. Ryan Island is located about where the Missouri empties into Fort Peck Reservoir when the latter is at its normal level. According to information obtained from the Omaha Office of the Army Corps of Engineers, the water level of Fort Peck Lake will usually be kept between the 2,234 to 2,246 foot level, when the main-stem dam projects downstream are completed. Of course in time of flood, the reservoir water will extend upstream for short periods, and during times of drought it will recede downstream.

A few active ranches and farms are located along or near the river bottoms in this stretch.

The Robinson Bridge on Montana State Highway 19 crosses the Missouri near the middle of this section, and the James Kipp State Park is on the south bank nearby. The land for this park was leased to the Parks Division of the Montana Highway Department by the Department of the Army in 1959. A temporary boat launching ramp, picnicking and camping sites, and toilet and water facilities have been provided, and these are receiving increasing use each year. In 1961, over 5,000 visitors made use of these facilities. A large majority come from Montana, North Dakota, and Canada. More and more Canadians are stopping here on their way to or from Yellowstone National Park and other American vacation points. However, the principal users of the facilities are fishermen in the summer and hunters in the fall.

The Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife, with some assistance from the Montana Department of Fish and Game, has improved wildlife habitat in the Game Range. For example, some bottomlands have been developed primarily through share crop agreements for irrigation of cereal and forage crops, such as rye, corn, winter wheat, barley, millet, alfalfa, oats and wild hay, for wildlife. Geese and ducks are nesting here in ever increasing numbers.

A few miles upstream from the Robinson Bridge is the Two Calf Mountain Sheep Inclosure where bighorn sheep were reintroduced in 1959. This area is managed cooperatively between the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife and the Montana Fish and Game Commission. A few miles downstream from the Robinson Bridge is the Sipary Ann Game Station, one of two administrative wildlife developments within the Fort Peck Game Range. A captive goose flock is kept here to raise young.

In the early 1950's approximately 300 elk from Yellowstone National Park were reintroduced in the Fort Peck Game Range. There is the possibility that buffalo may be reintroduced here sometime in the not too distant future.

According to an official of the Montana Department of Fish and Game, the area between Cow Creek and Fort Peck Lake contains the best deer hunting in Montana and is used by 15,000 to 20,000 hunters yearly, which represents about 10 percent of the hunters in the state.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

lewisandclark2/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jan-2008