|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

A Proposed Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway |

|

SUMMARY

The "Missouri River Breaks" is a name loosely bestowed on that section of the immediate Missouri River Valley which stretches approximately 180 river miles between Fort Benton and the Fort Peck Reservoir. The subject of recent investigations by the National Park Service, this is one of the big surprises in the current intensified program of National Park System planning. This is one of the blankest areas on the map of western United States. A ribbon of eroded land amidst the Great Plains relatively untouched by man--a wild area crossed by only one highway bridge and five obscure ferries--it had been generally assumed that this country was barren, sterile, and uninteresting. Field studies have dramatically shown otherwise. This country has outstanding park qualities--historic, scientific, and scenic. We believe that the best interests of American citizens and their posterity would be served if this area were to be preserved as a "Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway"--a name suggested by its character and both its historic and potential use.

The Missouri River, approximately 2,500 miles long from St. Louis to the Three Forks, is one of the Nation's most historic arteries. It was the primary route of Lewis and Clark on their epic journey of exploration. Long before the advent of transcontinental railways, it shared with the Oregon Trail and the Santa Fe Trail the distinction of being one of the three main thoroughfares to the Far West, witnessing a cavalcade of fur trappers, missionaries, gold rush miners, and pioneer settlers. But here, instead of covered wagons, conveyance was by pirogue, keelboat and steamboat.

|

|

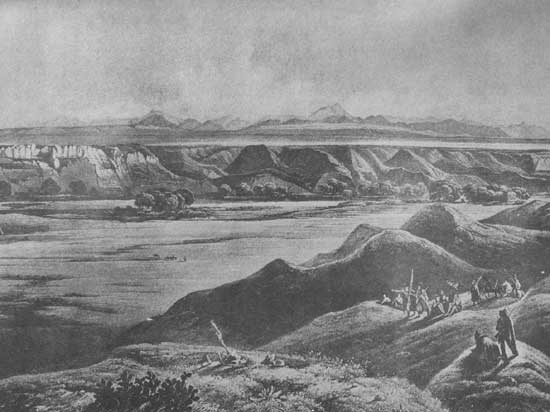

FIRST VIEW OF THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS. Bodmer Sketch - 1833

"Wile I viewed these mountains I felt a secret

pleasure in thus finding myself so near the head of the hitherto conceived boundless

Missouri; but when I reflected on the difficulties which this snowy

barrier would most probably throw in my way to the Pacific, and the

sufferings and hardships of myself and party in them, it in some measure

counterbalanced the joy I had felt in the first moments in which I gazed

on them...."

-- Meriwether Lewis - 1805

|

Wholesale reservoir impoundments, channel changes, and the development of towns and cities, bottomland farming, and industrial development along its banks have greatly altered the character of the Missouri River from Fort Peck Reservoir, Montana, downstream to its mouth, a distance of nearly 2,000 miles. Between Fort Benton and Three Forks, a distance of 300 miles, are the Great Falls of the Missouri, now heavily industrialized, several dams, and intensive bottomland farming. By some providence, there fortunately remains today a stretch of some 180 miles between Fort Benton and the Fort Peck Reservoir which retains much the same aspect as it did when seen by explorers, fur trappers, and steamboat passengers. By happy coincidence, it is this very section of the Missouri which contains the most impressive and unique riverside scenery along its continental course.

Lewis and Clark observed and recorded this unique scenery in 1805. Here, also, they observed an abundance of bighorn sheep, elk, deer, and antelope; places where Indians slaughtered buffalo by driving them over precipitous cliffs; and their first view of the Rocky Mountains. Here, too, subsequent to Lewis and Clark, this impressive scenery was observed by fur traders in keelboats and pilots of paddlewheel steamers whose per severance under great difficulty in pushing up this stretch of the river as far as old Fort Benton was in the finest tradition of American pioneering and westward expansion.

|

|

Paddlewheel steamers plied the upper reaches of the Missouri with

difficulty.

Bodmer sketch - 1833

|

Geologic aspects of the Upper Missouri River Country are most remarkable. Ice Age changes in the course of the Missouri River are an important part of the story of North America's Pleistocene epoch. In this section of the Missouri, the opportunity is ripe to interpret this phase of landscape alteration by the continental glaciers. Abandoned channels of the earlier Missouri River exist both north and south of the present youthful canyon.

The river cuts through a fine section of sedimentary rocks of Upper Cretaceous Age. Some formations (Colorado, Claggett and Bearpaw shales) were deposited under great seas which once covered this area and locally have concentrations of marine fossils. Other strata (Eagle sandstone, and Judith River formations) were deposited as great deltas and flood plain deposits on dry land following occasional retreats of these seas. Fossils of late Mesozoic dinosaurs and other Upper Cretaceous land animals are likely to be found in these beds. Interesting fossils of plants should be locally abundant here and there in these beds since they were deposited in the period when deciduous trees and other angiosperms evolved, so quickly to mantle the earth.

The alternation of marine and continental layers of the Upper Cretaceous in this area permits an interesting interpretive story to be unfolded and is represented in no existing National Park System area. Igneous intrusions penetrate the sediments as plugs and dikes. These are of early Tertiary Age and reflect mountain building processes which characterized the end of the Age of Dinosaurs.

Geologic forces have resulted in striking scenic features: large scale badlands cut to depths of as much as 1,100 feet by the main stream and its tributaries; white sandstone moulded by weathering and erosion into a series of fantastic forms which from some aspects resemble the ruins of classic Greek structures; perpendicular dikes of hard, dark intrusive rock which in several places is thrust up through the white sandstone in sharp contrast of color; dark brown walls which jut up vertically among the sandstone bluffs, with uniform thickness and profiles like an ancient ruin, and fractured into rectangular blocks of seeming human construction.

This portion of the Upper Missouri is also significant for the opportunities it offers for adventurous boating; for camping and picnicking in scattered cottonwood groves along its banks; for observation and photography of scenes like those painted by famous artists of western America such as Karl Bodmer and Charles Russell; and for visits to the sites of old military posts like Camp Cooke at the mouth of the Judith, old trading posts like Fort Benton at the head of navigation and Fort McKenzie situated near the Marias River, and steamboat landings like Brule Bottoms and Cow Island. Also, unusual conservation values exist in the wildlife habitat afforded by the rough, uncultivated lands which, if devoted in sufficient quantity to the purpose, would permit restoration of some of the former big game species.

"Here on both sides of the river, the most strange forms are seen, and you may fancy that you see colonnades, small round pillars with large globes or a flat slab at the top, little towers, pulpits, organs with their pipes, old ruins, fortresses, castles, churches, with pointed towers,..."-- Maximilian - 1833

The National Park Service is interested in preserving this section of the Missouri River because it possesses a combination of values which include: the last remaining unmodified stretch of the longest river in the United States; unique geological and wilderness values; exceptional scenic qualities; unexplored archeological features; excellent habitat for vanishing wildlife; the opportunity for rich boating experiences; and unusually rich historical associations.

Doubtless the most impressive historical association is that of Lewis and Clark. Certain pinpoint sites related to these primary explorers have been designated as of national interest. Fort Clatsop in Oregon is a National Memorial. Sergeant Floyd Monument in Iowa and Three Forks in Montana are Registered National Historic Landmarks. However, there is still lacking in the National Park System an inspiring example of the major river route which was the key to the success of this famous expedition. This portion of the Upper Missouri, if preserved, would provide a crowning memorial to the great explorers, and to their epic adventure, "the most important single expedition ever made under the auspices of our Government. "

We recommend preservation of this area as a Lewis and Clark National Wilderness Waterway, the more scenic White Rocks-Badlands Unit to be acquired by the Government and administered by the National Park Service; the less scenic and less primitive upper unit from Fort Benton to Virgelle to remain in its present ownership, but to be zoned, or otherwise controlled, to keep the river course and its immediate banks relatively undisturbed; and the Fort Peck Game Range Unit to remain under its present Federal ownership and administration, with the desired use of the land and preservation of its natural character assured through cooperative agreements between Federal and State agencies.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

lewisandclark2/summary.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jan-2008