|

OLYMPIC

Historic Resource Study |

|

VI. MOBILIZED FOR WAR: WORLD WAR II MILITARY INVOLVEMENT

Outbreak of War

The surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands on 7 December 1941 thrust the United States into the war between the Allied and Axis countries of the world. One day after the Pearl Harbor bombing, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution declaring that a state of war existed between the United States and Japan. On 11 December 1941 a similar Congressional resolution placed the United States at war with Germany and Italy. The United States thus became fully involved in World War II, a global war that would continue for nearly four years.

Japan's action at Pearl Harbor immediately spawned rumors and fears of a Japanese invasion of the western shores of the United States. Caught in a state of only partial mobilization, the U.S. hastily organized air, ground and sea defenses to protect the West Coast against immediate surprise attacks by Japan. In the Pacific Northwest, troops were hurriedly moved from one area to another; Puget Sound coastal defense forts built around the turn of the century were brought back to life; gun emplacements were erected at strategic points along the coast; and air surveillances were established lished throughout the Pacific Northwest (Schrader 1969, 1).

Many military personnel considered the Olympic Peninsula one of the most threatened and vulnerable parts of the contiguous United States. Forming the southern edge of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the Olympic Peninsula is located at the entrance to one of two principal inland waterways extending from the Pacific Ocean to strategically important Northwest coastal cities. The large ports of Seattle and Tacoma and the U.S. naval base and shipyard at Bremerton are accessed by the Strait of Juan de Fuca. (The Columbia River is the other ocean inlet which provides access to the interior ports of Longview and Vancouver, Washington, and Portland, Oregon (Webber 1975, 41).) Projecting further west into the Pacific Ocean than any other land mass in the conterminous United States, the Peninsula is the "leading edge," first to feel the effects of attack from an alien country approaching the U.S. from the west. In addition, the geographic isolation, rugged terrain and adverse climate of the Peninsula are factors that impeded terrestrial defense measures.

Northwest Sea Frontier

The United States Army, Navy and Coast Guard all became involved in the accelerated mobilization of defense of the Northwest coast, known during World War II as the Northwest Sea Frontier. The army, principally responsible for ground defense, was put on immediate alert at the three major coastal defense forts thus guarding the entrances to Admiralty Inlet and Puget Sound. These aged fortifications included Fort Casey on Whidbey Island, Fort Flagler on Marrowstone Island and Fort Worden at Port Townsend on the Olympic Peninsula. Fixed gun installations were planned for Cape Flattery, the northwesternmost projection of land on the Peninsula, the Striped Peak military reservation, fifteen miles west of Port Angeles. Antiaircraft weapons were relocated and emplaced at Ediz Hook, at the entrance to Port Angeles Harbor, and at various locations on Puget Sound, as well as at the Bremerton Navy Yard (Schrader 1969, 17; Webber 1975, 41-43). Within days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, army troops were "thinly scattered along the Washington coast from Canada to the Columbia River, and beyond, in anticipation of an invasion." At strategic sites west of Port Angeles, the strongest mobile defenses were established. Troops prepared for the destruction of certain bridges, such as the high level bridge across the Elwha River near the north coast of the Peninsula (Schrader 1969, 8).

By the spring of 1943, a joint agreement between the army and navy clearly articulated the broad role of the army in coastal frontier defense: "The general function of the Army in Coastal Frontier defense is to conduct military operations in direct defense of United States territory" (NARS:RG 26 1943, 10 April). The role of the navy in the defense of the Northwest coast was an integral and important part of the overall defense plan for the Northwest coastal areas. Broadly outlined in a 1943 letter, the commander of the Northwest Sea Frontier stated: "The general function of the Navy in Coastal Defense is to conduct Naval operations to gain and maintain command of vital sea areas and to protect the sea lanes vital to the United States, thereby contributing to the defense of the Coastal Frontiers." To accomplish these general functions, the navy was directed to establish a communications and intelligence system for sea defense and an information system utilizing coast guard stations, lighthouses and vessels (NARS:RG 26 1943, 10 April).

Coastal Lookout System

The U.S. Coast Guard, which transferred in entirety to the command of the navy on 1 November 1941 (slightly more than a month prior to the bombing of Pearl Harbor) played a vitally important role in what became known as the Coast Lookout System. This defense patrol system was instituted in the Atlantic Gulf and along the entire Pacific coastline. The threefold purpose of the Coastal Lookout System was to prevent communication between persons on shore and the enemy; to observe the actions of any enemy vessels in coastal waters and to transmit such information to naval or army commands; and finally, to report attempts of enemy landing to army and naval commands and to assist in preventing such action (NARS:RG 26 1943, 10 April). Coastal lookouts and lights, inlet patrols, life saving beach patrols and aircraft warning were some of the activities performed by the Coastal Lookout System.

Under the direction of the 13th Naval District, which took in the Washington and Oregon coasts, ten lighthouse stations were established as lookouts as early as November 1941. By late April 1942, twenty-six coastal lookout stations and thirteen lifeboat stations kept vigilant watch over the shorelines of these two states. And by June 1942 the Coastal Lookout System was substantially complete with army defense troops and civilian volunteers aiding coast guardsmen in the beach patrol and lookout efforts (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 5).

For purposes of military defense, all sections of the Northwest coast were inspected and mapped. In July 1942, the army, navy and coast guard working together conducted a meticulous survey of the entire Washington-Oregon coastline to determine the vulnerability of sections of shoreline for enemy landings. To facilitate the collection of data for this survey, the 13th Naval District was divided into three sectors with headquarters at Port Angeles, Washington, and Astoria and Coos Bay, Oregon (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 13).

|

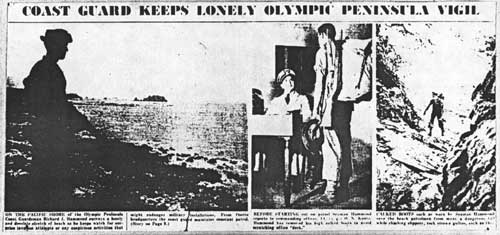

| A contemporary local newspaper described the World War II Beach Patrol activities of the U.S. Coast Guard, on the Olympic Peninsula. (Courtesy of Olympic National Park) |

The Port Angeles sector, extending from Cape Flattery south to Cape Elizabeth, a distance of approximately sixty-five miles, presented some of the greatest physical obstacles found anywhere in the country for establishing a defense lookout system. At the close of the war the 13th Naval District poignantly described the perils of this section of the Northwest coast:

As has been stated before, no other area in the country offered more disadvantages for patrols, particularly that portion on the western side of the Olympic mountains which forms the backbone of the Olympic Peninsula. Here lay one of the last primitive areas of the Northwest, an area covered with thick virgin forests whose undergrowth was practically impenetrable. The beaches were rocky and difficult to traverse. In some sections, the patrolmen would be obliged to climb and descend almost vertical walls. The many in-curving beaches were separated by walls of rock which projected out to the sea, and the Coast Guardsmen in order to ascend and descend these obstacles had to use lines secured to boulders or dwarfed trees atop the barriers (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 27).

Much of the rugged coastline occupied by guardsmen in the Port Angeles sector of the 13th Naval District is now included in the Coastal Strip of Olympic National Park.

Ozette Lake Coast Guard Station. One of the first moves by the 13th Naval District in the Port Angeles sector was to take over the army camp and patrols at the north end of Ozette Lake. On 1 September 1942 coast guardsmen and equipment left Seattle for Ozette Lake. Upon their arrival at Ozette Lake, army personnel at the lake departed. By the following morning the coast guard had established two primitive tent camps on the beach, three miles west of Ozette Lake. Within two weeks, tents were located at five beach camps, and trails were opened through the dense forests between the coast and the nine and one-half mile long Ozette Lake (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 28-29). The activities of the initial cadre of patrolmen in the Ozette Lake section were described by the War Diary Office:

The first patrolmen covered approximately twelve miles of rocky coastline each day, prepared their own meals over campfires, and slept on the damp ground at night. After three days, two additional patrols were established which provided complete coverage twice a day of the twenty-six miles comprising the Lake Ozette section. Each patrol remained on the beach for a period of from two to sixteen days, depending upon the availability of the men (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 29-30).

At the height of coast guard activity in the Ozette Lake section, ten beach patrol outposts and three coastal lookout towers were in operation. Spaced at regular intervals between Shi Shi Beach and Cape Johnson, the beach patrol outposts were located at Seafield, (at the mouth of the Ozette River), Cape Alava, Sand Point, Wink Trail, Yellow Banks, Township Trail, Allen Trail, Lone Tree Rock and Cape Johnson. The three lookout towers were positioned at Cape Alava, Eagle Point and the mouth of Starbuck Creek. Material used to build these beach cabins was transported by raft from Neah Bay or packed in by guardsmen. Trails either along the beach or through the woods, telephone lines, and fixed or portable radios facilitated communication between the beach patrol outposts, the lookouts and the patrol station at Ozette Lake (FARC ca. 1943a, n.d.; 1943, 26 June; War Diary Office ca. 1945, 31).

Established schedules and methods of patrolling the remote coastal areas in the Ozette Lake vicinity were described by the coast guard at the height of their activity at the Ozette Lake station:

Patrols 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 [beach patrol outposts west and southwest of the lake] leave [the] Station and return by boat on the lake to trails. . . . The men walk from the trail heads back to the different patrol camps . . . packing all supplies on their backs. The distances walked by the patrolmen from the Station to patrol camps vary from 2 to 6 miles over rough trails or beach. . . . Four men are present at each patrol section at all times, two being on the beach and two on rest. Patrolmen are relieved every four days, their period in the field being about 5 days. The watch schedule on the beach is on 6 hours and off 6 hours, the men preparing their meals, cutting wood, and maintaining their camps while on rest. Dogs are used on all patrols, all watches, and sentry dogs are kept at all camps all watches. Ozette Lake is patrolled daily by boat. Patrols 1, 2, 3, 4 and the Cape Alava Lookout [west and northwest of the lake] travel directly to their camps on foot (FARC ca. 1943a, n.d.).

In the Ozette Lake section, as well as coastal areas throughout Washington and Oregon, specially trained sentry dogs greatly facilitated the beach patrol efforts. Used as security guards in place of regular personnel assigned to duty on coastal lookouts, dogs were found to be extremely alert and were trained to investigate the slightest unusual disturbance. Dog patrols were instituted in the spring of 1943; in mid March 1943 a total of 200 dogs and forty-nine dog handlers were assigned to active beach patrol duty in the 13th Naval District. By June 1943, 463 dogs were on duty in the district. With a total of forty dogs and ten dog handlers, the Ozette Lake Coast Guard Station had the largest contingent of dogs of any coast guard station on the Washington and Oregon coasts (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 49-50).

While men and dogs were kept busy at patrol outposts and lookouts on the beach west of Ozette Lake, the beach patrol station at the north end of Ozette was a place of heightened activity soon after the arrival of the coast guard on 1 September 1942. Confronted with small, inadequate quartering and administrative facilities when they arrived, guardsmen immediately embarked on a project of constructing new station buildings. By the end of 1942, station personnel completed several buildings including a 150 x 20 foot barracks building, a storeroom and an armory (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 31). By mid 1943, the complex of coast guard structures at the nine acre Ozette Lake station consisted of two barracks buildings, a galley and mess hall, cook's quarters, two buildings (the "school house" and "Ozetta") for quartering men, ex-officer's quarters, a study and library building, an office building, a storeroom, dog kennels, two boat landings, and an assortment of outbuildings (FARC ca. 1943b, n.d.; NPS OLYM 1968, 1 August).

The activity of the beach patrol units in the Ozette Lake area, as elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest's 13th Naval District, were short lived. By the summer of 1943, the danger of enemy landings on the West Coast declined, and military officials felt that full beach coverage was no longer necessary. During the next several months, the allocation of personnel for the beach patrol was severely reduced. In September 1943, a new beach patrol operating plan called for a reduction in beach patrol activities, lowering the total complement of the Coastal Lookout System from 3,421 to 2,218 enlisted men. On 29 March 1944, beach patrol activities at Ozette Lake were discontinued (NARS:RG 26 1943, 4, 11 September; 1944, 26 February).

Little evidence remains in 1983 of the presence of the coast guard in the Ozette Lake area. At the north end of the lake the former coast guard station mess hall and kitchen is the only extant structure dating from the World War II beach patrol era. It has been subsequently altered and converted to the residence of the Park's subdistrict ranger for the Ozette area. Of the patrol outpost structures, only the small wood frame cabin at Starbuck Creek remains. Remnants of the trail system developed and maintained by the coast guard are still in use between Ozette Lake and the beach, and along Shi Shi Beach.

La Push Beach Patrol Station. Located near or within the present Park boundaries were two U.S. Coast Guard beach patrol stations. La Push Beach Patrol Station was located on the Quileute Indian Reservation at the mouth of the Quillayute River, and Kalaloch Beach Patrol Station was approximately twenty-five miles south of La Push. Both were headquarters for beach patrol outposts situated between Cape Johnson and Cape Elizabeth.

A coast guard unit at La Push was commissioned on 15 October 1942, and patrolling of the beaches began two and one-half months later. On 28 December 1942, guardsmen relieved army troops in the La Push area. The main U.S. Coast Guard beach patrol station was set up at La Push (outside the existing Park boundaries), and the patrol area, which extended from Cape Johnson south to Hoh Head, was divided into nine patrol subdivisions (NARS:RG 26 1942, 19 December; War Diary Office ca. 1945, 48).

Beach patrol outpost camps in the La Push unit were established at Toleak Point, Mosquito Creek, Mora and Third Beach. The patrol buildings at Toleak Point were remodeled trapper's cabins of frame and cedar shake construction and lined on the interior with plywood, while the Mosquito Creek patrol camp was of frame and tent construction. By mid June 1943, twenty-eight dogs assisted with the patrolling operations along the beach. Continuous day and nighttime patrols were maintained throughout the La Push area except just south of Cape Johnson and to the north of Hoh Head, where cliffs rising abruptly from the ocean made after-dark patrolling hazardous. As part of the Coastal Lookout System, the La Push Beach Patrol unit maintained a lookout tower on James Island and a light station on Destruction Island (NARS:RG 26 1942, 19 December; FARC ca. 1943c, n.d.; ca. 1943d, n. d.; War Diary Office, ca. 1945, 50).

Although coastal lookout activities along the Olympic Peninsula generally proved to be routine and unexciting, one of the most memorable events in the brief history of the beach patrol occurred in the La Push unit in the early spring of 1943. Near midnight on 1 April, rain, wind and heavy seas drove the Russian steamship Lamut ashore behind a jagged cluster of rocks just off Teahwhit Head. In the early morning light on 2 April, patrolmen found wreckage on the beach, and walking south along the beach sighted part of the grounded ship lodged between a hundred foot cliff and a small jagged rock island. Survivors of the wreck huddled high on the steeply sloping deck. High seas rendered a sea rescue impossible, so immediately coast guardsmen decided to attempt a rescue by land. By late morning members of the rescue party had cut their way through thick underbrush bordering the beach and ascended slippery boulders to the top of the cliff above the smashed ship. Using gauze bandage weighted with a rock, a light line was lowered to the eager hands of the stranded crew aboard the Lamut. Tying heavier line to the gauze, one line succeeded another until a life line strong enough to support the weight of a single person was stretched between the ship and the cliff. One by one survivors were raised to the cliff top and finally assisted down the landward side of the rocky ridge to the beach below. As darkness approached, the last of the Lamut survivors emerged from the swampy beach trail to waiting coast guard trucks and ambulances. The rescue of the Lamut crew was among the most dramatic events in the annals of World War II beach patrol history (Willoughby 1957, 52-53; War Diary Office ca. 1945, 98-100).

The La Push beach patrol unit, like that at Ozette Lake, lasted less than a year and a half. On 29 March 1944, the beach patrol ended and a week later the unit decommissioned (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 48). Portions of trails in the Mora subdistrict of Olympic National Park probably date from the era of World War II beach patrol activities. One small, collapsed wood frame cabin located at Teahwhit Head is believed to be associated with World War II beach patrolling activities in the La Push unit (Stokes 1983).

Kalaloch Beach Patrol Station. Adjoining and to the south of the La Push Coast Guard beach patrol unit, the Kalaloch beach patrol unit conducted patrol and lookout activities between Hoh Head and Cape Elizabeth. On 1 October 1942, the U.S. Coast Guard established a beach patrol station in buildings that comprised Becker's Ocean Resort. The forty-two acre coast guard station, located near the mouth of Kalaloch Creek on a low, sandy bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean, included the main resort lodge, eighteen resort cabins, a store and post office, and several storage and outbuildings. During its one and one-half years of occupancy, the coast guard expanded and adapted the complex of buildings at Becker's to suit the needs of the 140 enlisted men and officers who engaged in beach patrol and lookout activities. The coast guard constructed two barracks buildings, dog kennels and a laundry building at the station. Following a fire that destroyed the main lodge building on 8 January 1943, a mess hall, kitchen and refrigerator plant were erected near the site of the razed Becker's main lodge building (NARS:RG 79 1943, 1 March; Dickinson, Marian 1982; FARC 1943, 14 October; FARC 1943e, n.d.).

The beach patrol unit at Kalaloch was divided into nine patrol sections. Patrol outposts were located at Abbey Island, Steamboat Creek, Ashenbrenner, Queets River, Raft River, Hogs Back and Pratt Cliff. The coast guard erected shelter houses in each of the patrol sections and equipped them with two sleeping bags. As elsewhere on the Olympic Peninsula, four patrolmen were on each patrol section at all times—two at the shelter house and two actively engaged in patrol activities (FARC 1943, 14 October; ca. 1943b, n.d.).

Activities of the patrolmen at Kalaloch were described in a 1943 confidential report:

The actual patrol is made during the hours of darkness and during periods when visibility is decreased. In addition one early morning patrol at the break of day is the rule on all patrol sections. During periods of clear weather, the patrolmen maintain lookouts on well located vantage points. During foggy weather, constant patrols are maintained . . . . Each patrolman is armed with either a .30 caliber rifle or a .38 caliber rifle. Each pair of patrolmen is equipped with a portable radio and maintains hourly contact with the Kalaloch station. Very [sic] signal pistols are carried by each pair of patrolmen to be used in case the radio becomes inoperative. At night each pair of patrolmen is accompanied by a trained sentry dog (FARC 1943, 14 October).

In addition to the patrol outpost, 8 x 8 foot wood frame coastal lookout towers were located at Hoh Head and also at the mouth of the Whale River. Both lookouts were under the command of the Kalaloch Coast Guard Patrol Station (FARC 1943, 14 October; ca. 1943b, n.d.). Beach patrol activities at the coast guard station at Kalaloch were discontinued when activities at the Ozette and La Push Stations ceased on 29 March 1944. And on 4 April the Kalaloch unit was discontinued (War Diary Office ca. 1945, 48). By 1946 the coast guard encampment at Kalaloch resumed operation as Becker's Ocean Resort.

In the Kalaloch beach patrol section little trace of the coast guard remains. There are no outpost cabins known to exist. Becker's Ocean Resort, now Kalaloch Lodge, has experienced numerous changes since World War II. Most of the resort cabins used by the coast guard have been replaced by newer units. The barracks, mess hall and dog kennels at Kalaloch Beach Patrol Station are no longer standing.

Alrcraft Warning Service

In addition to the beach patrol and lookout activities performed by the U.S. Coast Guard in 1942 and 1943, several coast guard posts on the Olympic Peninsula coastline assisted with the Aircraft Warning Service operation. In the spring of 1943, several coast guard posts took responsibiity for sighting and reporting enemy aircraft. Aircraft Warning Service lookout posts were located at Tatoosh Island, Ozette, Cape Alava, Quillayute River, Kalaloch, Whale River and Destruction Island (FARC 1943, 8 March).

Under the direction of the U.S. Army, the Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) was initiated in 1942 when the threat of enemy air attack on the West Coast loomed large in the minds of many military strategists. Small ground based observation posts were activated throughout the Pacific Northwest beginning that summer and continuing through the winter of 1942-1943. AWS work, which was accomplished primarily by trained civilians, required twenty-four hour reporting of all planes seen or heard. "Flash" messages (aircraft sighted) were transmitted from AWS observation posts by telephone and included information pertaining to the number and type of planes, the altitude, and the flight direction of the planes.

The army established AWS observation posts in more remote isolated coastal and mountainous areas in the Pacific Northwest where inadequate radar screens existed. In many instances the National Forest Service and the National Park Service administered such isolated lands and thus became involved in facilitating AWS activities. The National Forest Service, in fact, became the coordinating agency for the establishment of AWS observation posts. In addition, already constructed Forest Service fire lookouts were often pressed into service as AWS observation posts.

|

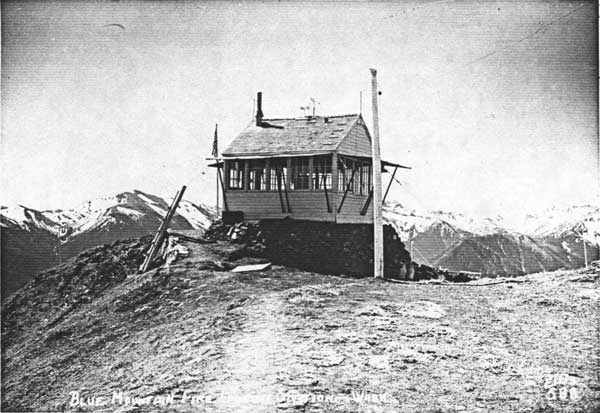

| The fire lookout perched on the 6,000 foot summit of Blue Mountain above Deer Park, was called into service as an Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) lookout during World War II. The building has since been removed. (Courtesy of Ellis Studio and Post Card Co.) |

On the Olympic Peninsula existing fire lookouts constructed by the Forest Service and located on both Forest Service land, and within the boundaries of the newly created Park, were often situated so as to afford unobstructed views out over the Pacific Ocean and the Strait of Juan de Fuca (NPS OLYM 1942, 9 January) In many instances new structures were constructed to add to the complement of already existing fire lookouts. Air warning stations within the 682,000 acre Park formed an important part of the defense system to protect the Puget Sound area.

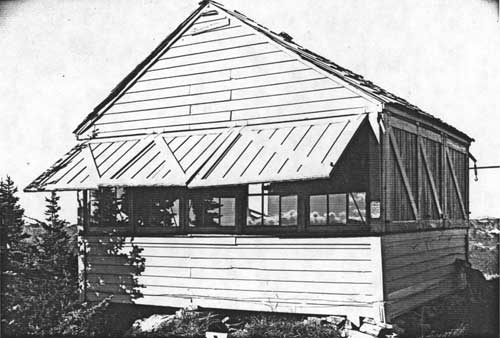

During the winter of 1942-1943, a total of thirteen Aircraft Warning Service observation posts located in the present Olympic National Park provided twenty-four hour surveillance (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1944a, n.d.). Already existing structures called into service for AWS purposes included Dodger Point, Deer Park and Hurricane Ridge fire lookouts (NARS:RG 79 1943, 10 November; NPS OLYM 1942, n.d.) and the Enchanted Valley Chalet (NARS:RG 79 1943, n.d.). New structures used specifically for AWS observation were erected at Pyramid Peak, Warkum Point, Indian Pass and Geodetic Hill (NPS OLYM 1942, n.d.; NARS:RG 79 1942, 29 August). A rock pile located one-quarter mile west of Constance Pass indicates that another AWS lookout existed there (Olson 1983). Only two structures in the Park utilized by AWS personnel during World War II are extant in 1983: Dodger Point lookout and Pyramid Peak lookout.

The Park Service assisted with Aircraft Warning Service operations in myriad ways during the one and one-half years of AWS existence. In the early months of aircraft observation activity, the Park Service furnished cots, CCC trucks (and sometimes CCC enrollees), tractors, men, and maps showing the topography of the Park and surrounding areas on the Olympic Peninsula (NPS OLYM 1942, 9 January). Park Service personnel constructed and cleared roads and trails to provide AWS observers clear access to lookout posts. They laid and maintained telephone lines where none previously existed. In some cases, the Park constructed AWS lookout towers. The drain on the Park's manpower and fiscal resources was great during this period as evidenced in a 31 July 1942 memorandum from Superintendent Preston Macy:

In connection with the operation of our Aircraft Warning Service for the U.S. Army we have been instructed to establish a station on Geodetic Hill for year long occupancy which involves the erection of a small shake cabin which will cost approximately $700.00. It will also be necessary for us to build a few short access trails and stub telephone lines. Later on it may be necessary to erect additional stations. The total expenditures will no doubt far exceed $1,500.00. . . . The demands made upon this office by the Aircraft Warning Service are attaining serious proportions and the situation is such that we must act with considerable speed in order to afford the Army the service required (NARS:RG 79 1942b, 31 July).

The Park's ranger force often devoted much of their time to transporting supplies to remote lookouts in the interior of the Park. During the stormy winter months of 1942 and 1943, considerable effort was expended in this endeavor. In the waning months of 1942 the Park superintendent's monthly report described the Park's efforts to transport supplies to Hurricane Ridge lookout: "All supplies are tobogganed over three miles of difficult terrain to Hurricane Lookout. It required two days and six men to get all supplies in. Eight men back-packed 400 pounds of supplies six miles in order to establish observers on a distant lookout in the Park area" (NPS OLYM 1942, n.d.).

|

| Dodger Point Lookout, built by the National Forest Service several years earlier for the purpose of siting forest fires, served as an Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) observation post during World War II. Dodger Point is one of only two remaining AWS lookouts in Olympic National Park. (Photo by M. Stupich, courtesy of National Park Service, Pacific Northwest Region) |

While AWS observers kept their twenty-four hour vigil during January and February of 1943, airplane movements over the Olympic Peninsula were extremely active. The army, in cooperation with the Forest Service, contemplated expanding the Park's thirteen AWS lookouts to twenty-four, and initiating high frequency radio stations (NARS:RG 79 1943, 13 March). Apparently no new lookouts were constructed, but in August 1943 ultra-high frequency radio service went into effect, greatly facilitating communications of the AWS (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1945, n.d.).

Between August 1943 and May 1944, AWS stations continued to operate; however, they were apparently shut down at certain times during the winter months. In that ten month period, 12,819 army "flashes" were made by AWS observers in the Park. With continued U.S. military successes against the Japanese in the Pacific, defense measures on the Pacific Coast gradually relaxed. On 1 June 1944 the entire AWS system was abandoned along the Pacific Coast, and all personnel were laid off (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1945, n.d.).

Japanese Incendiary Balloons

One final threat to the continental United States from Japan was the launching of some 9,300 incendiary balloons from the northern part of Japan's Honshu Island (Schrader 1969, 55). Between November 1944 and July 1945, balloons measuring thirty-five feet in diameter were recovered as far east as Michigan, and in Mexico, Canada, Alaska and Hawaii. Drifting across the Pacific by prevailing air currents and carrying from twenty-five to sixty-five pounds of incendiary bombs, the greatest incidences of balloon landings were in the western states of Oregon, Washington, Montana and California. A total of twenty-five balloons, or parts of balloons, landed in Washington. Two were recovered on the Olympic Peninsula—one at Vaughn (Gig Harbor) on 28 February 1945, and the other at Chimacum on 13 March 1945 (Mikesh 1973, 69-81).

As part of a U.S. military countermeasure, the Fourth air force initiated a defensive system known as the "Sunset Project," early in April 1945. In an attempt to detect Japanese balloons as they approached the Washington coast, radar sites were established at Quillayute, Ruby Beach and Queets (Mikesh 1973, 34-36).

As with other U.S. defense measures undertaken on the Olympic Peninsula, Olympic National Park was involved in operations to sequester the Japanese incendiary balloons. Soon after balloons were first sighted, all Park ranger personnel attended bombing school training at Yosemite or Fort Lewis, to get the latest instruction on how to handle and what to expect from these fire bombs. According to Superintendent Preston Macy: "It was not necessary to put such training into practice although a number of Jap fire balloons were seen over the park and remains of one or two were found within the boundaries" (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1945, n.d.). In the summer of 1945 the local Port Angeles Evening News reported:

Several Japanese balloons were seen in the air in this area, but according to information from forest and park supervisors and the sheriff's office none landed. "We often wondered what happened to them ourselves," said Preston Macy, Olympic National Park supervisor. Macy said that balloons, believed to be Japanese were sighted over Deer Park and near Hurricane Ridge (NPS OLYM 1945, August).

Throughout the four years of U.S. involvement in World War II, and especially during the time of military defense activities on the Olympic Peninsula, Olympic National Park cooperated with all the branches of the armed forces in numerous subtle yet significant ways. Within the Coastal Strip and the Queets Corridor, then known as the Olympic acquisition area, the Park Service issued special use permits for coast guard and army use of Becker's Ocean Resort, Ruby Beach Resort, Thunderbird Inn at the Washburn Resort, C. W. Keller's Resort (located in the Coastal Strip), and Kelley's Ranch (on the Queets River) (NARS:RG 79 1942, 5 October; ca. 1944a, n.d.; ca. 1945, n.d.). On the boundary of the Park's Morse Creek addition the Park Service issued the army a special use permit for the designation of an "Impact and Hazard Area" in connection with army tank gun target practice. On the coast the Park granted permission for the removal of 130,000 tons of sand from Rialto Beach for use in completing the Quillayute Air Base (NARS:RG 79 1943, 10 November).

On many occasions during the war personnel from both the military and the Park Service exchanged services on various missions. Olympic National Park personnel instructed groups of military men in fire fighting techniques, assisted in airplane rescue work and organized recreational trips into the Park. While men of the 15th Cavalry were stationed at Port Angeles, the Park opened the swimming pool at Olympic Hot Springs for their use. On several occasions the U.S. Coast Guard took Park personnel on flights over the Park for study purposes. Both the navy and coast guard supplied the Park with men to fight forest fires (NARS:RG 79 ca. 1944a, n.d.).

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The sudden attack on Pearl Harbor and the vulnerability of the Washington coast generated a brief period of concerted defensive activity along the Northwest coast. The thousands of military and civilian personnel who participated in the Coastal Lookout System, and the Aircraft Warning Service defended the Pacific Northwest from the threat of a possible invasion along an inaccessible and largely undefended coastline. Later on, as the threat of invasion subsided, the incendiary balloons brought new fears and new efforts at defense.

But the perceived threats diminished rapidly and the defensive effort ended almost as suddenly as it started. Structures thrown up for shelter were, in most cases, abruptly abandoned and soon disappeared. Heroic deeds, like saving the Russian Lamut crew, only rarely punctuated an otherwise uneventful defense effort. Today, some understanding of the deep concern generated in the early days of World War II may still be gained in interpreting several structures as well as some of the trials established by the Coastal Lookout System. Within the Park, two former coast guard structures are still extant, the Ozette Ranger Station and the cabin at Starbuck Creek, and offer some opportunity for interpretation. Similarly, of the thirteen Aircraft Warning Service lookouts once in use, only Dodger Point and Pyramid Peak survive to remind the visitor of the frightened and earnest efforts made at coastal defense in the earliest days of World War II.

REFERENCES CITED

| 1982 | Dickinson, Marian Becker. Interview with author. Port Angeles, Washington, 17 August. |

| (FARC) Federal Archives and Record Center, Seattle, Washington. (RG) Record Group 26. | |

| 1943 | 8 March. Map. Northwest Sea Frontier, Northwest Sector, Naval Local Defense Forces, Naval (Coast Guard) Coast Lookout System. Confidential. FRC 19096. |

| 1943 | 26 June. Map of patrol camps by V. I. Storland, S4c. Clallam Bay. FRC 19096. |

| 1943 | 14 October. Coast Guard Beach Patrol Station, Kalaloch, Washington. Coast Guard Station, Forks. FRC 19096. |

| ca. 1943a | n.d. CG Station, Clallam Bay, Washington. FRC 19096. |

| ca. 1943b | n.d. CG Station, Forks, Washington, Coast Guard Station, Forks, Washington. FRC 19096. |

| ca. 1943c | n.d. CG Beach Patrol Station, La Push, Washington, Coast Guard Patrol, La Push, Washington. FRC 19096. |

| 1943d | n.d. District Coast Guard Officer—Thirteenth Naval District. Personnel, District Coast Guard Officer—Thirteenth Naval District. FRC 19086. |

| 1943e | n.d. Week ending 6 March 1943. War Diary, Seattle, Thirteenth Naval District. FRC 19086. |

| 1973 | Mikesh, Robert C. Japan's World War II balloon bomb attacks on North America. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. |

| (NARS) National Archives and Record Service. Washington, D. C. (RG) Record Group 26. U.S. Coast Guard. | |

| 1942 | 19 December. Coast Guard War Diaries. |

| 1943 | 10 April. Military Readiness Division World War II. Navy-Coast Guard Relationship. Letter from Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, U.S. Navy, commander, Northwest Sea Frontier. |

| 1943 | 4 September. Coast Guard War Diaries. |

| 1943 | 11 September. Coast Guard War Diaries. |

| 1944 | 26 February. Coast Guard War Diaries. |

| (RG) Record Group 79. National Park Service. | |

| 1942b | 31 July. Memorandum from Preston P. Macy, superintendent, to the director. Central Classified File, 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (630). |

| 1942 | 29 August. Memorandum from B. F. Manby, assistant regional director, to the director. Central Classified File, 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (620). |

| 1942 | 5 October. Memorandum from Preston P. Macy, superintendent, to the director. Central Classified File: 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (601-03). |

| 1943 | 1 March. Memorandum from B. F. Manby, acting assistant superintendent, for the files. Central Classified File: 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (901). |

| 1943 | 13 March. Superintendent's Monthly Report for the Month of February, 1943. Central Classified File: 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic. |

| 1943 | 10 November. Memorandum from Preston P. Macy, superintendent, to the director. Central Classified File: 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic. |

| 1943 | n.d. Olympic National Park. List of Concessioners as of June, 1943. Central Classified File, 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (900-05). |

| 1944a | n.d. Superintendent's Annual Report, 1944 F.Y. by Preston P. Macy, superintendent of Olympic National Park. Central Classified File, 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (207-01.4). |

| ca. 1945 | n.d. Superintendent's Annual Report, 1945 F.Y. Central Classified File, 1933-1949. National Parks: Olympic (207-01.4). Photocopy. |

| (NPS OLYM) National Park Service. Olympic National Park. Unaccessioned historical papers. | |

| 1942 | 9 January. Memorandum to the director. National monuments, Mount Olympus, administration and personnel reports, monthly narrative, superintendents. Photocopy. Port Angeles, Washington. |

| 1942 | n.d. National monuments, Mount Olympus, administration and personnel, reports, monthly narrative, superintendents. Photocopy. Port Angeles, Washington. |

| 1945 | August. Twenty Jap balloons found in Washington: None in area. Port Angeles Evening News. Port Angeles, Washington. |

| 1968 | 1 August. Transcription of interview with Vince Storland with sketch map. Port Angeles, Washington. |

| 1983 | Olson, Richard. Interview with author. Port Angeles, Washington, 16 August. |

| 1969 | Shrader, Grahame F. The phantom war in the Northwest. N.p.: N.p. |

| 1983 | Stokes, Richard. Interview with author. Port Angeles, Washington, 30 October. |

| ca. 1945 | War Diary Office. Thirteenth Naval District. United States Coast Guard. History of Beach Patrol: 13th Naval District. N.p.: N.p. Typescript. |

| 1975 | Webber, Bert. Retaliation: Japanese attacks and Allied counter-measures on the Pacific coast in World War II. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. |

| 1957 | Willoughby, Malcolm F. The U.S. Coast Guard in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hrs/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 01-Oct-2009