|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART XI:

LIVING IN THE PAST, PLANNING FOR THE FUTURE

Introduction

This chapter covers the monument's history from late 1970, when Area Manager Raymond J. Geerdes left Pipe Spring, to early 1979, when Superintendent Bernard G. Tracy retired. The highpoints of the decade were the dedication of the Kaibab Paiute Cultural Building/Visitor Center and National Park Service-Kaibab Paiute Tribe joint-use water supply system on May 26, 1973; and the monument's two-year celebration of the country's bicentennial with an expansion of its living history program.

In 1970 President Richard M. Nixon was in the middle of his first term in office. Nixon's second term was clouded by the Watergate scandals and ended in his resignation on August 9, 1974. He was succeeded by Vice-president Gerald R. Ford who later was defeated in the 1976 elections by James Earl ("Jimmy") Carter. During the early 1970s, the United States moved toward military disengagement from its long involvement in the civil war in Viet Nam. The roots of U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia went back to the Truman era and, like the Korean War, were the product of Cold War foreign policy. After sending military advisors from 1955 to 1960, the U.S. government became directly embroiled in the conflict, sending military troops from 1961 to 1973. In 1973 U.S. troops were withdrawn while the federal government continued its support of the South Vietnamese government and military. In 1975 the Saigon government surrendered to the North Vietnamese-backed Provisional Revolutionary Government, ending the war. [2107] The same year U.S. troops were withdrawn from Southeast Asia, another international conflict erupted in the Middle East. The Arab-Israeli War of October 6-22, 1973 (also called the Yom Kippur War), led to an Arab embargo of oil shipments to the United States. The resulting energy crisis resulted in a host of measures being implemented to curb energy consumption by individual citizens, businesses, and governments and to spur the development of additional energy sources. The fuel shortage appears to have contributed to a 21 percent drop in visitation to Pipe Spring National Monument in 1974.

President Nixon's cuts in funds for the Office of Equal Opportunity led to the cancellation of many Community Action programs such as the Neighborhood Youth Corps (NYC), Head Start, and Operation Mainstream in 1973. [2108] While the monument struggled to retain the area's NYC program and keep its interpretive program afloat in the early 1970s, it received a boost during the country's bicentennial celebration. Beginning in 1976, enrollees under the Comprehensive Employment Training Act (CETA) program furnished workers for the monument. Volunteers in the Parks (VIPs) also became increasingly essential to the monument's interpretive program, especially in cattle branding and domestic arts demonstrations.

A number of Park Service administrative changes took place during the 1970s. Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall's long tenure in the 1960s was followed by five changes in the Secretary's position between 1969 and 1977, made in the following order: Walter J. Hickel, Rogers C. B. Morton, Stanley K. Hathaway, Thomas S. Kleppe, and Cecil D. Andrus. Fewer changes were made to the directorate. Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., served until December 31, 1972. Shortly before his departure, Hartzog reinstated the Superintendent's Annual Report to the Director. (This report had been discontinued in 1964.) Hartzog was succeeded by Ronald H. Walker (January 1, 1973-January 3, 1975), Gary E. Everhardt (January 13, 1975-May 27, 1977); and William J. Whalen (July 5, 1977-May 13, 1980).

Of more direct impact to Pipe Spring National Monument were administrative changes made on the regional level. The monument fell under the direction of three different regional offices during the 1970s. At the beginning of the decade the monument was overseen by Regional Director Frank F. Kowski of the Southwest Region. On November 15, 1971, the boundary of the Midwest Region was adjusted to include Utah, Colorado, and at least part of Arizona. Most likely because of the monument's close historical association with and geographic proximity to Utah, the administration of the monument was transferred to the Midwest Regional Office in Omaha, Nebraska, on that date. Regional Director J. Leonard Volz then headed that office. The monument remained under his direction until January 6, 1974, when the Rocky Mountain Region was established in Denver, Colorado. The monument then fell under its oversight. Regional Director Lynn H. Thompson oversaw the Rocky Mountain Region until Glen T. Bean succeeded him in 1978. Bean held this position until early 1980.

Until July 1972, the monument remained under the administration of the Park Service's Southern Utah Group. Acting General Superintendent Bill R. Alford succeeded General Superintendent Karl T. Gilbert on September 19, 1971; Acting General Superintendent James W. Schaack replaced Alford on January 9, 1972. The Southern Utah Group was abolished on July 8, 1972, after which time the monument was again placed under the direct management of Zion National Park. Zion's superintendents included Robert I. Kerr (May 3, 1970-July 8, 1972), Robert C. Heyder (July 9, 1972-June 2, 1979), and John O. Lancaster (June 3, 1979-May 16, 1981).

During the 1970s, there were numerous changes in personnel at the monument. For information on historians, technicians, seasonal aids, and laborers, see the "Personnel" section. For information about work performed by enrollees in the Neighborhood Youth Corps and Comprehensive Employment Training Act programs and by Volunteers in the Parks, see separate sections under those headings.

Monument Administration

Area Manager Ray Geerdes left Pipe Spring National Monument in early October 1970. Southern Utah Group's Park Naturalist James W. ("Jim") Schaack was appointed acting park manager to look after the monument until a permanent manager could be hired. The only noteworthy events to take place under Schaack's four-month tenure were tied to the placement of all the monument's power lines underground. The power line installation project required GarKane Power Company to excavate a trench of about 1,730 feet to a minimum depth of 42 inches. Archeologist Richard A. Thompson of Southern Utah State College was employed to conduct a preliminary survey to ensure that no archeological resources were destroyed during the project. [2109] GarKane's work began in November and was completed by December 2, 1970.

Superintendent Bernard G. Tracy, GS-09, entered on duty at Pipe Spring on February 14, 1971, moving into his office in the 12 x 54-foot trailer still used at the time as the visitor contact station. [2110] Former superintendent of Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, Tracy would oversee monument operations for most of the decade. Tracy later recalled that when General Superintendent Karl Gilbert offered him the assignment at Pipe Spring, Gilbert said, "All I ask is that you run Pipe Springs as near as you think it used to be in the early days. Think of that period, one hundred years ago." [2111] Raised in Arizona and California, Tracy considered himself a native. Although he was not a Mormon, his wife Ruth was a devout member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This undoubtedly hastened the new couple's acceptance by the local Mormon community.

Earlier in his career, Bernard Tracy had been a vineyard owner in California. Prior to his tenure at Hubbell Trading Post, Tracy had worked at Capitol Reef National Park, notable for its historic fruit orchards. He thus had considerable experience with agricultural operations and took to his new assignment at Pipe Spring with relish. Such activities, however, were only made possible by the additional water the monument had access to after its construction of a new well and water system on reservation land, and through an agreement reached after lengthy negotiations with the Kaibab Paiute Tribe. A good deal of Tracy's time would be taken up during his first year at Pipe Spring in meetings with the Tribe as the Park Service sought to build on joint planning activities begun in the late 1960s (see Part X for background).

Construction of the Park Service Well

On January 12, 1971, Chief Gerard S. Witucki and Hydrologist Donald C. Barrett, both of the Water Resources Section, National Park Service's Western Service Center (WSC), held a pre-construction conference at Pipe Spring National Monument between the contractor, monument staff, and the U.S. Geological Service (USGS). [2112] Park Service personnel attending the meeting were General Superintendent Karl Gilbert, Acting Park Manager Jim Schaack, Civil Engineer William ("Bill") Fields (Southwest Regional Office), Maintenance Foreman Mel Heaton, and Park Guide Joe Bolander. Fields was also chief of the Indian Assistance Program as well as former chief of Water Rights, Western Office of Design and Construction. Hydrologic Technician E. L. Gillespie represented the USGS (Flagstaff office) at the meeting. The Tribe's economic development planner, Merle C. Jake, did not attend the meeting but accompanied the men during the selection of a well site at Two Mile Wash. A location agreeable to all was selected by the USGS. [2113] That afternoon Park Service staff met with the Tribal Council to discuss plans for the new well. On January 19, Chief Witucki authorized the district chief of the USGS in Tucson, Arizona, to conduct pump testing of test wells. Funds in the amount of $2,000 were available for the testing part of the project. (This figure was later increased to $3,500.) The Western Service Center supervised and financed the drilling of the well on the Kaibab Indian Reservation.

Hydrologist Barrett returned to the area in early February 1971. On February 9, he traveled to Fredonia, Arizona, and met with USGS Hydrologist E. McGavock and Hydrologic Technician Gillespie to discuss the drilling results and geo-hydrologic problems involved in obtaining water from the alluvium of Two Mile Wash and adjacent Moccasin Wash. A chief consideration in choosing a well site was that pumping not impact the existing well at Moccasin or Pipe Spring. Four non-productive wells had been drilled so far and a fifth well was in the final stages of drilling by the time of Barrett's arrival. On January 10, the drilling of the fifth test well was completed, which proved also to be dry. The tests indicated that no dependable alluvial source of water existed in the Two Mile Wash area. [2114] What water was present in the surface drainage was of very poor quality. The men agreed that a successful well might be completed in a structural trap in the Navajo Sandstone bedrock rather than in the alluvium. Barrett spent February 10-12 in the area studying the situation. He obtained approval from the Western Service Center to have the contractor drill a well at a site selected by McGavock, two miles north of the monument, then made arrangements for a road to be put in to the well site. Finally, he met with the contractor in Hurricane on the 11th. The men worked out a proposed design for the new well and tentatively agreed to necessary changes in the contract schedule for drilling into the bedrock, at a depth expected to be about 200 feet.

Hydrologist Barrett returned to the area on March 25, 1971, to evaluate the pumping test, to make recommendations for the completion of the well, and to discuss a change order with the contractor. He later reported to WSC Director William L. Bowen that the maximum yield of the well appeared to be on the order of 150 gallons per minute or more. The water quality was good, derived from a bedrock aquifer. "Just what long term effects this yield will have on the water reserves of the aquifer cannot be accurately foretold at this time (e.g., mining the waters)," Barrett wrote. [2115] The well was to have been a test well, but because of certain drilling requirements relating to the geology of the area, it was drilled as an eight-inch well at a depth of 205 feet. This resulted in it being classified as a production well.

During the last week of March 1971, a master plan study team met at Pipe Spring. Several meetings were held with the Kaibab Paiute during that time which convinced General Superintendent Gilbert that quick action on the new Pipe Spring water system was of the utmost importance. Gilbert reported to Regional Director Frank F. Kowski in late March that the well was a good one, capable of producing 150-200 gallons per minute. While the well had been drilled with the Tribe's permission, no agreement had been executed for the future use of the well, Gilbert emphasized. The meetings just held with the Indians were amicable, wrote Gilbert, and he did not think working out a water agreement with them would be difficult. He made the following observations:

Since quantity of water seems to be no problem, the Park Service should look toward an agreement that would make possible the use of the total Pipe Spring spring flow within the monument for the historical preservation of the area. I suggest we consider giving the Indians, free of charge, an amount of water (approximately fifteen gallons per minute) equal to their spring right, to offset their use of spring water. Beyond this, I suggest we furnish them water at cost of production.

The Indians have advised us that they are now ready to move on their planned construction projects adjacent to Pipe Spring. They tell us their intent is the immediate construction of a modern campground and the possible construction of a motel-craft store-service station complex. They now have a sizable Tribal Council-office building completed.

This proposed construction puts us behind the '8-ball' because the Indians have suggested the possibility of their putting in a temporary water system utilizing the new well, a small metal tank, and plastic pipe until such time as we can provide the system we hope to install.

Based on the overall existing picture, I believe the Park Service should move ahead as fast as possible on the Pipe Spring water system. [2116]

While the construction program for fiscal year 1972 budgeted only for plans and surveys of test wells, Gilbert argued that construction of the new well needed to be completed that year as well. He asked Kowski to find funds for that purpose, stating, "I believe it to be extremely important for the overall preservation of the area, and necessary to insure that the monument's historical integrity will not be damaged by hit-and-miss construction by the Indians." [2117] The funds were found.

A few days later Gilbert sent Kowski an agreement he had drafted relating to the use of the new well drilled by the Park Service on tribal land. He asked for the regional director's review and comment. In his cover letter, Gilbert wrote,

This agreement should be as short as possible, yet all-inclusive. It should not indicate that the Indians are giving us anything or that we are selling them water from their own reservation. Now is not the time to think of the NPS acquiring any additional water rights from the spring.

This agreement is urgent; we can't mark time and still keep in good stead with the Paiutes. They want to move, and will move if we sit idly by. [2118]

Park Service officials had urged the Tribe to take advantage of its Indian Assistance Program for some time. Evidence of a positive response came in late March when Tribal Chairman Bill Tom submitted a formal request to Gilbert for assistance:

The Kaibab Paiute Tribe is planning economic developments in the Pipe Springs area and are aware that it is necessary to provide for a cooperative approval to mutual problems. The Council has learned that you have a staff that can lend assistance to our planning. Therefore, it would be appreciated if you would assign some of your staff to work with our people in the preparation of a land use and development plan for the Pipe Springs area. [2119]

This request was music to Park Service ears. The road ahead, however, would not be an entirely smooth one.

|

|

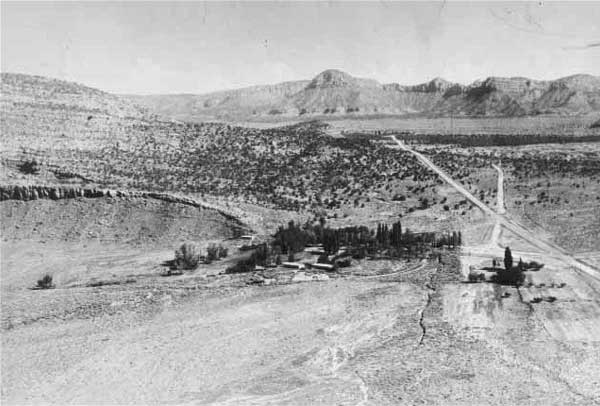

123. Aerial view of Pipe Spring National Monument, April 1971 (Courtesy William E. Fields). |

Planning the Water System and Kaibab Paiute Cultural Building/Visitor Center

Gilbert knew the time had come when a joint area-management agreement needed to be established with the Kaibab Paiute Tribe. Two meetings were held in April 1971 to discuss the new water system and tribal development program. The first is believed to have been held the week of April 11; no description of this meeting has been located, however. The second meeting was held on April 26, 1971. Participants at this meeting included Bill Tom, Karl Gilbert, Bernard Tracy, several Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) representatives, an undisclosed number of Indians from other tribes, and Ed Huizingh and others representing the Economic Development Association (EDA), and U.S. Department of Commerce. [2120] The group narrowed down the Tribe's projected plans to a campground, visitor center, and a small commercial complex consisting of a camp store, sales outlet for arts and crafts, and possibly a service station. It was agreed that plans for a motel would be delayed until proof of need was established. The EDA contingent was pleased with the overall plan but said that EDA assistance could be based only on a projected job establishment program after construction of the complex was complete. They suggested a maximum grant of not more than $300,000. Gilbert proposed a water agreement that was well received at the meeting, he later reported. The EDA representatives indicated such an agreement would relieve the Indians of much responsibility and investment.

Although the meeting went well, Gilbert was still apprehensive. In reporting on the meeting to Kowski, he wrote, "I am still convinced that we should not drag our feet in working with this group of Indians. The over-all development plan is most important at this time; we must be able to talk in specifics rather than in generalities. We all are spinning our wheels until such time as we can pinpoint what is to be." [2121] His intuition was right on target. The Park Service's new well was completed on May 16, 1971. On June 28, 1971, Park Service officials learned from Merle Jake that the Tribe had scheduled three projects for fiscal year 1972: 1) a public campground and trailer park; a public museum (to be located just outside the monument's east boundary gate); and 3) three new residences. All would require water. Jake informed the Park Service that if it were unable to develop a joint water supply in time to meet the Tribe's needs, the Tribe would be required to develop their own water system from the new well. This threatened to eliminate the chance of a Park Service agreement with the Tribe at a later date. The Tribe, in effect, was planning to "go it alone" with its developments at this point, despite its earlier interest in Park Service participation in the process. Immediately, on June 28, 1971, monument and Zion officials submitted a construction proposal for the new water system to the regional office.

The Kaibab Paiute Tribe's plans to develop its own museum and water system may have resulted from what Gilbert later referred to as a temporary "breakdown in communications." Communications were restored in a meeting held on July 14, 1971, in the Tribe's office and headquarters. The meeting was attended by Landscape Architect Volney J. Westley (Southwest Region), Karl Gilbert, Bernard Tracy, Bill Tom, Merle Jake, Ferrell Secakuku (Indian Development District of Arizona), and representatives of an architectural firm retained by the Tribe to conduct a feasibility study and to prepare development plans, working drawings, estimates, and specifications for tribal developments. [2122] It was learned in the meeting that tribal officials misunderstood the water agreement drafted by Gilbert and thought the agreement limited their use of water from the new well to an amount equal to one-third share of Pipe Spring water (approximately 22,000 gallons per day), when in fact it allowed for them to use more water at cost of production. The misunderstanding was corrected.

The purpose of the July 14 meeting was to develop a realistic understanding about cooperative uses and construction of proposed facilities. Regional Director Kowski later reported on the meeting to Phoenix EDA representative Paul Luke, informing him that the Park Service and the Tribe recognized the importance of close cooperation in development planning. The Park Service proposed that a formal agreement be executed whereby it would construct and maintain a water system that would meet the needs of both agencies, with the Tribe permitted to derive its one-third interest in Pipe Spring from the new well at no charge. Additional water could be purchased by the Tribe at cost of production. In return, the Tribe would allow the Park Service to use its one-third share of spring water to maintain the historical landscape of the monument. A second agreement was to be executed for a proposed "visitor center complex" which, at that time, the Tribe proposed building with the Park Service leasing a portion of it for offices and a visitor center.

On July 30, 1971, Tribal Chairman Bill Tom sent a revised version of Gilbert's draft water agreement back to Gilbert for review and comment. It had not yet been discussed or approved of in Tribal Council, he informed Gilbert. [2123] Gilbert had a number of strong objections to the revised version, which he noted in his cover letter transmitting the draft agreement to Regional Director Kowski on August 9. [2124]

Another meeting was held on August 24, 1971, just one day after a heavy rainstorm and serious flooding at the monument (see "Floods" section). This purported "get-acquainted" meeting turned out to yield useful information and some decisions. Director Ben Riefel, Office of Indian Programs, accompanied Gilbert. Also attending were Bill Tom, Construction Superintendent McIntosh, and BIA Lands Operations Officer Al Purchase, Hopi Agency. Gilbert learned at this meeting that the revised version of the water agreement sent to him by Tom on July 30 had actually been written by Al Purchase. The proposed joint-use visitor center was also discussed. Before the Park Service ever began its cooperative efforts with the Tribe, the BIA had prepared plans for its own visitor center across the road from the tribal office building. Gilbert later wrote Kowski, "These plans continually raise their ugly head and will come alive if we don't assert continuing interest in plan input based on our projected requirements." [2125] As a result of this meeting, however, the Tribe reversed its plans to seek planning assistance from a commercial firm and asked for National Park Service assistance. The Tribe's most immediate project was construction of three residences, then scheduled to begin September 1, 1971. This created an urgent need to settle the water question.

In the midst of critical negotiations with the Kaibab Paiute Tribe, an administrative change took place in the Park Service. General Superintendent Gilbert was scheduled to leave the Southern Utah Group on September 18, 1971, to become superintendent of Curecanti National Recreation Area. In anticipation of his transfer, Gilbert advised Kowski in late August to assign a Kaibab Paiute liaison from the Southwest Regional Office. "Superintendent Tracy is a good man on the ground floor," he wrote, "but major dealings involving decisions and agreements should be handled at a higher level." [2126] Acting General Superintendent Bill R. Alford succeeded Gilbert as head of the Southern Utah Group on September 19, 1971.

By October 1971, the Tribe decided it wanted the Park Service to design the new joint-use building and to take part in choosing its site. Another meeting was held on October 19 for the purpose of considering on site a design concept for the visitor center developed by the Western Service Center's Office of Environmental Protection and Design. Deputy Regional Director Theodore R. Thompson, Volney Westley, and Bill Fields (all Southwest Region), Acting Superintendent Jim Schaack (SOUG), Tribal Chairman Bill Tom, and Superintendent Bernard Tracy attended the meeting, along with other monument staff. The group consensus was that the location proposed by the WSC office was undesirable and there were other suggestions for changes. Alternatives were suggested and subsequently sent to the WSC by Thompson who asked if the WSC could provide the architectural plans for the building. [2127]

In addition to the siting of the proposed visitor center, the group discussed the desirability of relocating existing Park Service housing outside the monument. A flood of August 23, 1971, had once again alerted the Park Service to the hazards of having residences located in a natural drainage channel (see "Floods" section). Flood protection would be extremely expensive, requiring a sophisticated drainage channel and riprap. Since the Park Service was already involved in the preparation of the Tribe's new subdivision plan northeast of tribal headquarters, why not move monument housing to that area and negotiate a lease agreement? This proposal in fact was included in the draft 1972 master plan for Pipe Spring National Monument and had been approved by Southwest Region officials. When the monument's administration was transferred to Midwest Region on November 15, 1971, however, the idea was quashed; officials there did not support the concept. A report by a Regional Engineer Donald M. McLane also convinced officials at Midwest Region it was unnecessary to remove the housing area. [2128] (The idea of relocating the residences would be revived again in the late 1970s.)

During December 1971, Tracy met informally with Tribal Chairman Bill Tom to discuss the joint visitor center complex. The Tribe was anxious to start construction on March 1, 1972. On January 20, 1972, a meeting between the Park Service and the Tribal Council was held to study preliminary plans for the new Kaibab Paiute Cultural Building/Visitor Center (hereafter referred to as the visitor center). [2129] Bill Tom presided over the meeting. Representing the Park Service was Bernard Tracy, Jim Schaack, and Regional Architect A. Norman Harp. Also attending were representatives of the BIA and the Indian Development District of Arizona (IDDA). Harp presented a preliminary sketch to the Tribal Council for its consideration. The plan included a snack bar, public restrooms, arts and crafts area, as well as office and exhibit space for the Park Service. The Council voted unanimously to accept the plan. It was agreed at this meeting that the Southwest Region's Professional Support Division (rather than the Western Service Center) would prepare working drawings for the building, parking area, landscaping, and drainage. Harp promised the working drawings would be completed by February 20, 1972, less than one month away. The Council asked that the Southwest Regional Office also design its campground. Harp agreed to send preliminary plans for the campground by February 1. At this meeting the Tribal Council voted to raise the budget for the new building from $85,000 to $125,000. Tom stated the Tribe would construct the building with day labor, with subcontracts for electrical, plumbing, and mechanical work. The BIA agreed to provide supervision for the project. Norm Harp later recalled that the building design was never presented to the local Moccasin or Fredonia communities for review or comment. [2130]

Ferrell Secakuku applied to the Economic Development Administration for a portion of the funds required to construct the visitor center and tribal campground. [2131] Harp provided Secakuku with cost estimates for the visitor center and the campground in late January 1972. The grand total was $212,750: $157,750 for the visitor center, and $55,000 for the campground. [2132] Park Service space in the building had yet to be negotiated through the Government Services Administration (GSA). [2133] In July 1972, a formal request for space was sent to GSA for the Park Service to lease space in the planned building.

Construction of the new visitor center began during the summer of 1972. [2134] Local materials were used in much of the building's construction. Harp recalled years later that his design called for local stone, not only because it was readily available, but also because it would make the new building "look sort of like the old fort." [2135] The ventilators on its roof also were similar to those on the fort. Phil Huck (from the BIA's Indian Technical Assistance Center) supervised day-to-day construction activities. [2136] Bill Fields conducted a monthly inspection, representing the Park Service through its Indian Assistance Program. Fields later recalled that the Kaibab Paiute were hired mostly as laborers on the project. Not many Indians were hired for the project because they didn't have the construction skills needed, he reported. [2137] Dean Heaton (son of Leonard Heaton) was hired with EDA funds as construction foreman. Heaton set up a hiring office in Colorado City, which turned out to be the primary source of skilled workers used to build the visitor center. Of course, Regional Architect Norm Harp was also very involved in the project and made routine inspection visits to the construction site. Harp recalled that one of the men in Southwest Region's Division of Professional Services involved in producing the working drawings for the visitor center was Engineering Technician Edward ("Ed") Natay. [2138] Architectural services were provided by the Park Service without charge to the Tribe, as were the services of Bill Fields. According to Harp, the whole construction operation went very smoothly.

Harp and Fields visited the area on July 18-20, 1972. Harp made a progress inspection of the building, still under construction. Fields later reported,

The building is in excellent shape. They are almost to the windows with the rock work and were putting shakes on the roof while we were there. The workmanship is superior and I might add that in my personal opinion, because of the combination of design and workmanship, this building will be the most sound and one of the most beautiful to be utilized by the Park Service. [2139]

In a personal interview conducted in 1997, Fields recalled the urgency of the project, and why the Park Service didn't go through the normal channel of having the Western Office of Design and Construction in San Francisco design and produce architectural plans for the building:

The system did not lend itself to getting something done in a hurry. And I'm not saying it's right or wrong. You know, if they want to dilly dally about what a building looks like and get input and they're not in a hurry to have it. But we had $170,000 or whatever in the bank and ready for Bill Tom and Phil Huck and whoever else to write checks on, and we needed a building! You're not going to go through the review process [under those conditions]. And I think we did pretty good.... I said, 'Norm, this is what we want.' There's not a better architect in the Park Service than Norm Harp....That guy can do anything from an outhouse to a multistory building or penthouse. And he has the artistic ability.... He went out there, took some pictures, came in and started drawing that thing, and it couldn't be better. [2140]

But there were still hurdles ahead. By mid-August 1972, the visitor center was nearing completion. No word had been received from GSA regarding the Park Service's request to lease space in the building. Upon inquiry, the Park Service was told it would take another six to eight weeks for the GSA to contact the Tribe and make arrangements for a lease. Tracy was uneasy at the delay, for a possible change on the political horizon threatened the Park Service's existing amicable relationship with the Tribe. On August 18, Tracy wrote Regional Director J. Leonard Volz,

I have just been alerted to a possible change in the local Paiute Tribal Council. Their election is to be held this fall and the aspirant to the Chairmanship is an activist with definite anti-white leanings. Should he be elected we could be in a completely new ball game as far as our relations with the Tribe are concerned. I suggest an agreement for the rental of the Visitor Center be negotiated at the earliest possible date. [2141]

Tribal elections were scheduled for October. The Park Service asked GSA officials to expedite the leasing process. On September 7, 1972, a meeting was held with GSA Building Manager Richard C. Hathaway, Superintendent Tracy, and Zion's new Superintendent Robert C. ("Bob") Heyder. Hathaway informed Heyder and Tracy, who wanted a long lease, that any lease in excess of five years required an Act of Congress. As it turned out, Bill Tom was re-elected tribal chairman. A lease with the Tribe was not executed until March 29, 1973, when Tom signed a five-year lease on 1,831 usable square feet of office space for $12,636 per year. [2142] The lease included an option to renew for five additional years at a rate to be negotiated. In addition to giving monument staff greater control over visitor use, the new facility allowed them to provide an orientation to visitors prior to their entry to the site. It also provided much-needed office and storage space, improving the monument's overall operations.

|

|

124. Program to dedicate new Kaibab Paiute Tribal Cultural Building/Visitor

Center, May 26, 1973. Speaker is Regional Director J. Leonard Volz, Midwest Regional Office (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

125. View of visitor center and crowd gathered for its dedication, May 26, 1973 (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

126. Visitor center ribbon-cutting ceremony, May 26, 1973. Officials, from left to right: Regional Director J. Leonard Volz, Tribal Chairman Bill Tom, Superintendent Bob Heyder (Photograph by William M. Herr, courtesy Zion National Park, neg. 4457). |

|

|

127. Kaibab Paiute dancers at visitor center

dedication, May 26, 1973 (Photograph by A. Norman Harp, Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

128. Superintendent Bernard Tracy stands behind new

visitor center, May 26, 1973 (Photograph by William M. Herr, courtesy Zion National Park, neg. 4433). |

The new visitor center was dedicated on May 26, 1973. A grand celebration was held for the completion of the building and the Park Service's near-completion of the new water system. The 50th anniversary of the monument's establishment was also celebrated. [2143] Regional Director Volz was Master of Ceremonies that day, with over 400 people attending the event. Ceremonies began with Moccasin's Boy Scout Explorer Troop 2368 presenting the colors, followed by the Fredonia High School Band playing the national anthem. The invocation was given by Elder A. Theodore Tuttle, First Council of the Seventy (LDS Church) after which Tracy formally welcomed guests. Remarks were made by Arizona Governor Jack Williams, Utah's Executive Director Gordon E. Harmston (Department of Natural Resources), and former Custodian Leonard Heaton. Tribal member Dan Bulletts offered a benediction in Paiute. Although not listed on the program, a group of Kaibab Paiute came in costume to the dedication and danced, encouraging visitors to join in. Both tribal members and local white residents provided food for the event. The official photographer on the day of the building's dedication was William M. ("Bill") Herr, then working for Zion National Park. [2144] Herr would be named superintendent of Pipe Spring National Monument in 1979.

Other groups that helped with the planning and/or execution of the dedication program included the Kaibab Ward Relief Society Ladies and the Zion Natural History Association, along with Park Service staff from the Midwest Regional Office and Zion National Park. The printed program stated that Pipe Spring was not only a monument to "the intrepid Mormon pioneers," but was "symbolic of the union of many cultures and their need to maintain harmonious relationships with the world about them." [2145] Soon, other park units who had relations with Indians were seeking to learn how Pipe Spring had accomplished its joint projects with the Tribe, with the monument providing an impressive model for others to follow. [2146] The new building was indeed a remarkable achievement, but cooperation between the Park Service and the Tribe would by no means end with the building's dedication.

The Water Agreement and Park Service Construction of the Water System

On April 13, 1972, the Park Service and Kaibab Paiute Tribe signed a water agreement (see Appendix VII, "Agreement with Kaibab Paiute Tribe"). The agreement was sent to the Tribe's attorney and to the Park Service's field solicitor for review and approval prior to its signing. The 25-year agreement provided that the Park Service would construct, operate, and maintain the new well and water system. In return, the Tribe agreed to allow the Park Service to use their one-third rights to Pipe Spring. In lieu of Pipe Spring water, the Park Service would provide a specified amount of 7,884,000 gallons of water per year from the new well at no charge. The Tribe agreed to pay the cost of production for all water they used during any one year in excess of the specified amount. While the Park Service retained ownership of the water system, in the event the agreement was terminated the Tribe had the right to purchase the equipment at the then-appraised value. Both parties agreed to use waters of the well and Pipe Spring economically with the objective of conserving it. Well water could not be used for commercial agriculture. It was the Park Service's responsibility to meter all water and annually bill the Tribe for water in excess of the specified amount. The Park Service agreed to pay an annual rental charge for use of well water at a rate of $33 per acre foot. Should the output of Pipe Spring exceed the monument's needs, the Park Service agreed to make excess water available to the Tribe. The Tribe at its own cost could install a pipeline connecting the water well lines with the Kaibab Village system for emergency purposes only. The Tribe retained one gallon per minute flow from Pipe Spring for livestock watering purposes. Finally, the Park Service had the option to renew the contract for another 25 years upon its expiration. [2147]

The new water system was engineered and financed by the Park Service. Ray Wyrick of the Western Service Center made preliminary surveys, Noby Ikeda of the Denver Service Center (DSC) made the construction layout, and the DSC's Office of Environmental Planning and Design prepared plans and specifications. [2148] The contract for construction of the water system was awarded to Stratton Brothers Construction Company of Hurricane, Utah, for $155,891.50. [2149] Notice to proceed was issued on February 13, 1973. Construction work, consisting of reservoir excavation, access road grading, and placing of six-inch water line started on February 13, 1973. Work was performed during an unusually wet winter. All construction was completed on June 12, 1973. With the exception of 737 feet of six-inch underground pipeline and two fire hydrants located on monument land, the water system was located on the Kaibab Indian Reservation. The well was located in a small side canyon, a distance of just over two miles from the monument and one-half mile from Kaibab. A small pump house was located directly over the well; the balance of the system was underground, including a 500,000-gallon cement reservoir. A Wallace and Tiernan A-475 chlorinator was also part of the system. It was reported at the time that the pump was capable of producing 150 gallons of water per minute.

Administration Gets Back to Normal

Since the new visitor center had public restrooms, during 1973 the monument's cinder block comfort station, built in 1957, was razed. To further restore the historic landscape at Pipe Spring, the Park Service had long encouraged the Tribe to develop a picnic area on the reservation. A picnic area just east of the monument was under development by the Tribe in 1973, thus the Park Service decided to remove its over-taxed picnic area within the monument. By 1974 the monument's picnic area was removed as well as the old asphalt-surfaced parking area on the monument's east side. Trees and other vegetation were planted to obliterate the site.

The monument finally instituted collection of entrance fees on July 30, 1973. This was the first time that fees were ever collected in the monument's 50-year history. Tracy attributed the 21 percent decline in visitation figures from 24,051 in 1973 to 19,007 in 1974 to a number of factors: 1) reduced travel due to the energy crisis in the early part of the year; 2) removal of the picnic grounds from the monument; 3) institution of fee collection; and 4) improved accuracy of counting resulting from fee collection. Many of the monument's past visitors were local residents who had been coming to the monument for picnics and recreation several times a year for decades. Once they were required to pay an entrance fee, Tracy reported, many chose not to visit the monument or came less frequently. [2150] While that may have been the case initially, a report three years later by Tracy stated that local residents came "as many as six to eight times per year," bringing visiting family and friends. [2151]

With the Arab oil embargo in place by the fall of 1973, all park units were required to conserve energy and to report how they implemented this policy, beginning with 1973 Annual Reports. Tracy reported from 1973 through 1975 that temperatures and lighting were kept at minimum levels. No more reports on monument energy use were made until the Superintendent's Annual Report for 1979. On November 15, 1979, emergency building temperatures were put into effect and several other measures were taken to reduce energy consumption. New wood burning stoves were installed in both Mission 66 residences and six-inch under floor insulation was also installed. (Former Custodian Leonard Heaton, who once complained of the residence having no backup heating system and cold floors, would have given his whole-hearted approval to both measures!) Old incandescent lighting fixtures in bedrooms, dining rooms, kitchens, and bathrooms were replaced with fluorescent ceiling fixtures, resulting in an additional energy savings.

On June 25, 1975, an official operations evaluation was conducted at Pipe Spring. A later report stated, "The team was impressed with the monument as a little gem of a historical area especially in the manner in which it is presented to the public." [2152] The team thought the historic buildings were well maintained and had that long sought after "lived-in" look that gave visitors the feeling of stepping back in time. The new visitor center and concessions run by the Tribe were an improvement in visitor services, they reported. Although the Tribe's maintenance of the building was not quite up to Park Service standards, the working relationship with the Tribe was satisfactory. [2153] The team praised the monument's interpretive program, but cautioned that care needed to be taken "to keep it within reason as far as staffing and costs are concerned." Among the needs identified was for permanent positions for a clerk-typist, to help with office work, and a ranch foreman, to handle the farm and ranch work of the interpretive program. In its long list of recommendations, the team wrote that the construction of a new maintenance and storage structure should be given high priority.

During 1976 the monument began monitoring air quality with readings taken twice daily, morning and evening. Visibility observations were made in order to establish visibility standards for the monument and the Arizona Strip to the south. The data was sent for use in developing a model to the Assistant to the Regional Director James R. Isenogle for Utah who coordinated the Park Service's air quality control program. [2154] Also that year the Kaibab Paiute Tribe proposed to build a large, one-story, multi-purpose center about one mile north of the monument using grant funds from the Economic Development Administration. The center was needed, the Tribe stated, to combat the problem of alcoholism among its members. [2155] The new project would serve a population of about 200 Kaibab Paiute. The estimated cost of the new building was $250,000. The construction of the building took some time. Dedication of the Tribe's new multi-purpose building took place on December 22, 1978. Merle Jake was master of ceremonies at the event. Bill Fields, Southwest Region, gave the keynote address and Gevene E. Savala conducted the ribbon cutting. Paul Smith (Tribal Operations, Phoenix Area Office) made closing remarks, with Mel Heaton offering the closing prayer. [2156]

At the beginning of the 1976 travel season, Tracy met with the tribal chairperson to make suggestions for improving the appearance and operation of the visitor center. He later submitted a list of suggestions to the Tribe's chairperson, not "to be construed as a request or directive," he wrote, trying to be diplomatic. [2157] This appears to be the first time that Park Service expectations were so clearly spelled out to the Tribe for its upkeep of the building.

A problem arose in the fort during 1976 that took much time and money to address. Water seepage along the fort's north wall worsened that year. The consulting firm of Conron and Muths, Restoration Architects, from Jackson, Wyoming, was engaged to research the problem and make recommendations for treatment. (See "Historic Buildings" section for details.) Emergency action was required during November 15- 16, 1976, which resulted in the removal of the fort's parlor and kitchen floors. This created a new storage problem for the monument. A place was needed to temporarily store all the furnishings that were removed from the two rooms. It was decided that a room in the visitor center would be used. There was much concern about moving the artifacts from a cool area of high moisture to the warmer and much drier visitor center. Regional Curator Ed Jahns provided the monument with a sling psychrometer in January 1977 for relative humidity readings to be taken in the new storage room, as well as in the storage trailer. He provided instructions for increasing the humidity where the "damp room" (i.e., parlor) furnishings were stored, and advised staff to gradually lower it over several months until it reached the normal humidity of the fort. He advised that the furnishings not be kept in the visitor center for longer than a year. [2158]

Tracy did his best to control the humidity in the visitor center storage room. Without introducing humidity through mechanical means, the normal humidity was about 25-26 percent. When he attempted to humidify the room by mechanical means to the 40-50 percent that Jahns recommended as a "starting point," the furnishings began to accumulate a surface residue, which appeared to Tracy to be mineral in nature. In addition to his concern about the collection, Tracy was also concerned about visitors' complaints about the closure of the two rooms of the fort. Local residents in particular were in the habit of bringing their out-of-town guests to see the fort and couldn't understand the lengthy closure of the rooms. Tracy asked Heyder for permission to construct a temporary plywood floor in the fort rooms so furnishings could be put back in and full tours could be given again. Heyder forwarded Tracy's request to the Rocky Mountain Regional Office, stating that he opposed doing anything in the two rooms before the report of Conron and Muths was received. [2159] (That report was submitted in November 1977. See "Historic Buildings, The Fort" section.)

Another serious problem occurred during the summer of 1977, this time interfering with normal operations in the visitor center. The building was connected to a 1,500- gallon septic tank, which proved inadequate to meet the needs of visitors and staff. During the summer, the system became blocked and inoperable. Sewage backed up into the snack bar, forcing its closure for a short period. The visiting public and staff were without restroom facilities for three days. As a temporary measure the septic tank had to be pumped out about once a week. Visitors inconvenienced by the problem at first held the Park Service responsible, but were usually appeased after the problem was explained to them. [2160] The problem was solved with the Tribe's installation of a new sewage lagoon prior to the 1978 travel season. [2161]

In the spring of 1978, the Government Services Administration renegotiated a new five-year lease between the Park Service and Kaibab Paiute Tribe for rental of the monument's office space and visitor center. Tracy reported the lease was improved over the earlier lease. [2162]

The most noteworthy event of 1978 was the completion of the monument's master plan in March. Much had transpired in the way of Park Service-Tribe cooperative developments since the previous master plan of 1972. By 1978 Glen Canyon National Recreation Area was drawing increasingly large numbers of motorists from southern California past the monument on Highway 389. The master plan recommended additional exhibits, the development of a self-guiding nature trail and audio stations, and the re-creation of ranch land, orchards, vineyards, and vegetable gardens. It also proposed relocating the monument's residential and utility areas to tribal land, either in the Tribe's new housing area east of the monument or in a small cove located about one-half mile north of the monument. This proposal would receive thorough study in early 1979, after Tracy had retired (see Part XII).

In late 1978, Tracy advised the Park Service of his plan to retire, which he did on January 12, 1979. He agreed to oversee the monument as a retired annuitant until the arrival of Superintendent William M. ("Bill") Herr, GS-11, on April 8, 1979. [2163] After that date Bernard and Ruth Tracy moved to Moccasin and lived there until 1996, when they moved to Salt Lake City to be near family.

Visitor Services Operated by the Kaibab Paiute Tribe

Campground

Like the visitor center, the Tribe's campground was designed by the Park Service's Southwest Regional Office through the Indian Assistance Program. Bill Fields recalled that the Park Service "did the plans, the specs, the layout; we hired people, rented backhoes; we dug the trenches; we put in the water lines and sewer lines, parking spaces, curbs, and everything." [2164] There was not enough money to complete the campground's construction in the early 1970s, however, nor to build 70-units, as originally planned in 1972. [2165] Begun about 1973, the 45-unit campground and trailer park was completed in 1977. [2166] The full-service operation was located about one-quarter mile northeast of the monument. In addition to the usual necessary hookups, a laundromat, restrooms, and showers were available. Tracy provided field inspection services for the project during its final construction phase. The facility was put into use in 1978 but was not heavily used that year. (Tracy attributed low use of the campground to it not being well advertised.) Again in 1979 the campground had very little use. It was reported that the Tribe did not have anyone to operate it properly, the grounds were not taken care of, and the grocery store was seldom open. One of the monument's seasonal maintenance men parked his trailer there all summer and watered the trees around his campsite, the only ones that were watered. Many people with recreation vehicles drove in, around, and right back out of the campground, monument staff reported. [2167]

Snack Bar and Gift Shop

From the time the visitor center was first planned, the Kaibab Paiute Tribe intended to develop the south part of the building for a food service operation and gift shop (also referred to as the arts and crafts shop). By the end of 1973, the Tribe was in the process of negotiating a contract with an individual to operate the gift shop and provide food services. During the summer of 1974, Dennis ("Denny") Judd of Kanab operated the gift shop. The Tribe operated a snack bar during the summer of 1974. Tracy reported that both ventures did well that first year. The following year he reported the snack bar appeared to be a "thriving business" during the summer of 1975.

During the summer 1976, however, the snack bar was only open for about 10 days. Its operator told Tracy that the amount of business did not justify its operation. Denny Judd continued to operate the gift shop during the 1976 travel season but expressed doubt that he would continue to run the shop in 1977 due to poor sales. The Tribe sought new leasees for both operations. Doug Higgins of Holbrook, Arizona, leased the gift shop and the snack bar in 1977. He found the gift shop profitable, but not the snack bar. After that season he informed the Tribe he would not continue operating both businesses and that, if required to operate the snack bar, he would terminate his lease for both operations. The Tribe allowed him to lease only the gift shop space in 1978; he reported it was a very good year for business. That summer two members of the Tribe operated the snack bar. They too reported a good season. No one was hired by the Tribe to operate the snack bar in 1979 until the end of the summer season. The operators kept it open for two or three weeks then disappeared. Doug Higgins ran the gift shop again in 1978. Monument staff received a number of negative comments about the type and quality of goods Higgins sold, which were mostly from Mexico. [2168]

Since the building was tribally owned, the Park Service had no direct control over its leased operations or building maintenance. Tracy recognized the need to use tact to ensure that all facilities were managed to the Park Service's high standards. At least in 1974 and 1975, Tracy reported that the Tribe was offering good service in its maintenance of the building.

Hiking Trails

In 1968 Tribal Chairman Vernon Jake had been amenable to Ray Geerdes' suggestion that the Park Service construct trails to the Powell survey monument and through Heart Canyon. Nothing was done to build the trails at that time, however, probably because Neighborhood Youth Corps enrollees were busy constructing the monument's own trail. On May 15, 1972, Tracy wrote Tribal Chairman Tom and asked for the Tribe's permission to construct and maintain a two-mile walking trail from Pipe Spring to the Powell survey monument, returning through Heart Canyon where petroglyphs are found. He requested a 10-year agreement with option to renew. The Tribe forwarded Tracy's request to Hopi Agency at Keams Canyon. They in turn asked Tracy to provide them with a legal description and map showing the proposed location of the trail. During his July 18-20, 1972, trip to the area, Bill Fields completed several surveying jobs for the Tribe at its request. While they had asked him to stake a nature trail from Pipe Springs to the Powell monument, Fields decided to not to stake the trail. "A more sound understanding and agreement should be reached between Park Service and the Tribe prior to the staking of the nature trail," Fields reported. [2169] For reasons unknown, no agreement was executed. Six years later, in 1978, the Tribe completed two trails that connected to the monument's trail system, one to the Powell monument and the other to Heart Canyon. [2170] The Park Service had long desired to administer trails to these sites as part of their interpretive program. Since their construction, the Tribe has administered the trails.

Developments in Kaibab Village

In late June 1974, the Tribe's water well in Kaibab Village failed - the only source of water for the community. The Tribe invoked Clause 13 of the 1972 Memorandum of Agreement with the National Park Service that provided that "the Tribe at its own cost and expense may install a pipeline connecting the water well lines with the Kaibab Village for emergency purposes only." On June 21, 1974, the Tribe connected to the main water line and relied on the Park Service well for the rest of the summer. [2171] By September 1974, the Indian Health Service had completed preliminary design of a new water source and storage system for 12 proposed housing units to be erected in Kaibab. [2172] Superintendent Bob Heyder advised Tribal Chairman Bill Tom that since the emergency connection was above ground and subject to freezing, the Park Service would be able to continue supplying water only until the onset of winter. [2173] On September 30, 1974, the Tribe's well was put back into service and reliance on the Park Service's well ended. The monument provided a total of 1,510,200 gallons of water, which was metered and chlorinated. As stipulated in the 1972 water agreement, the Tribe was billed $386.01 for the cost of water production. [2174]

In 1975 it was determined that the Tribe's well was no longer adequate for its needs. Drilling operations for a new well commenced in the area of the Park Service's well. On May 15, Tracy informed Heyder that one well was drilled about 1,300 feet northeast of the Park Service well to a depth of 290 feet. No water was found and the site was abandoned. As of mid-May a second well was being drilled about 700 feet southwest of the Park Service well. Drilling was suspended at a depth of 80 feet to make repairs to the drilling rig. The driller advised Tracy at that point that he didn't think water would be found at that site and he intended to suggest drilling next beside the Park Service well, as it was a proven water source. Tracy recognized the danger. He suggested in a report to Heyder that the Park Service offer to supply water to Kaibab Village rather than see its system jeopardized by another nearby well. The well log indicated that the current pump was able to produce 250 gallons per minute with no difficulty, Tracy wrote. Under those circumstances, a completely new water agreement would be required with the Tribe. [2175] As it turned out, the Tribe drilled a new well near the monument well in 1980 (see Part XII).

Neighborhood Youth Corps, Comprehensive Employment Training Act, and Volunteer Programs

NYC Program

The monument continued to rely on enrollees of the Neighborhood Youth Corps program through the 1974 summer season. In 1971 there were 18 NYC enrollees, 11 girls, and seven boys. (Seven of the girls were Indian and four were whites; five of the boys were Indian and two were white.) The NYC enrollees contributed 3,473 hours during that summer. At the conclusion of the 1971 summer's NYC program, two summer aids were hired, three girls (two Indian, one white) and one boy (Indian). They contributed an additional 238 hours of work to the monument. [2176] While most of the Indian workers were Kaibab Paiute during the early 1970s, some enrollees were Navajo, Havasupai, and Hopi. As in prior years, boys were engaged in maintenance work (carpentry, plumbing, painting, tending gardens and orchards, irrigation, and caring for poultry and livestock), under the supervision of Mel Heaton. The girls worked as interpretive guides in the fort demonstrating baking, quilting, weaving, churning, and other "pioneer" domestic arts. As in earlier years, girls were costumed and the boys wore work clothes.

In January 1972, Tracy learned that the NYC program coordinating office for Mohave County was being transferred from the Flagstaff to Yuma, with the possibility that there might be no program in the Pipe Spring area. In addition, the Arizona Strip was in danger of losing its Head Start and Operation Mainstream programs. [2177] Tracy and the area's Neighborhood Council (representing Kaibab, Moccasin, and Fredonia) wrote a number of letters pleading with state officials to keep the NYC program going on the Arizona Strip. [2178] Indian children made up the majority of Head Start and NYC programs; 85 percent of enrollees in the NYC program were Indian and half of these worked at Pipe Spring National Monument.

|

|

129. NYC crew take a break from work, July 27, 1971. From left to right: Danny Bulletts, Brigham Johnson, Glen Rogers, Elwin John, Ingo Heaton, and Supervisor Mel Heaton (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

|

|

130. NYC girls by fort gate, August 3, 1971. Front row,

left to right: Amelia Baker, Ila Bulletts. Back row, left to right:

Supervisor Konda Button, Laurie Heaton, Gloria Bulletts, Bonnie Choate,

and Maeta Holliday (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

Operation Mainstream was also an important avenue for adult vocational training. Tracy was assured in early February by the Manpower Planning director for Yuma and Mohave counties that the NYC program would be continued, at least for the time being. Tracy proceeded to line up students to fill the usual 18 slots. Just four days before the enrollees were to begin work at the monument, Tracy received word indirectly that the program had not been scheduled or funded because the area was too remote to justify a program. Chagrined, he wrote Governor Jack Williams about the problem, commenting on the youthful lament of the 1960s, "I am continually hearing the young people refer to the short comings of the so-called ESTABLISHMENT, and I am beginning to believe they have a point." [2179] He appealed to the governor to restore the area's NYC program and funds. Williams asked the director of Manpower Planning to get the problem straightened out and Tracy got his program and funds back. The program was reactivated on July 3, one month late in the season. That summer there were 14 NYC enrollees, eight girls and six boys (nine Indians, five whites). [2180] In addition, one Paiute boy was hired through Dixie College's off-campus work study program.

In February 1973, Tracy resumed the monument's annual letter-writing campaign to state and county officials to plead for the continuation of the NYC program at Pipe Spring. The female enrollees provided over 80 percent of the monument's summer interpretive program, he informed State Director Adolf Echeveste, Office of Economic Opportunity. The program was continued at the monument that year, but a report of the number of enrollees has not been located.

In 1974 the living history program was operated on a much more limited scale than in prior years due to a decline in scope of the state-sponsored NYC program. The monument was unable to obtain workers directly through the NYC program that year but the Kaibab Paiute Tribe ran its own NYC program and had a surplus of youth. In 1974 the Tribe programmed five of their enrollees to assist with maintenance work and the living history program at the monument. During its last year of operation at the monument in 1975, eight NYC enrollees worked, six girls and two boys (three girls and one boy were Kaibab Paiute).

CETA Program

Beginning in the summer of 1976, the monument was able to obtain workers through the state's Comprehensive Employment Training Act Program (CETA). The CETA enrollees provided essential seasonal staff, particularly for the monument's interpretive program. CETA girls worked as interpreters and CETA boys performed maintenance work. In 1976 there were 11 enrollees, five girls and six boys. In 1977 there were nine CETA workers, six girls and three boys. During 1978, there were 10 enrollees (nine girls and one boy) and in 1979, nine enrollees (eight girls and one boy). During the late 1970s, Seasonal Park Aid Adeline Johnson supervised the CETA girls. [2181]

The VIP Program

Volunteers in the Parks (VIPs) continued to contribute to the monument's interpretive program during the summers. [2182] Men and women took part in distinctly gender-differentiated activities during the 1970s, much as they did in the 1870s. (For additional information on VIPs, see "Interpretation" section.)

Cattle Branding Demonstrations

Male volunteers were responsible for cattle branding demonstrations. It is not known how many branding demonstrations were given in 1971; in 1972 there were four branding demonstrations. The cost for the roundup and branding demonstrations in 1971 and 1972 was $600 each year. Two branding demonstrations were offered in 1973 and again in 1974. Three were given in 1975. During 1977, VIPs participated in branding demonstrations and in the monument's third annual wagon trek. Due to a shortage of funds for VIPs, only one branding demonstration was held on Saturday, May 27, 1978. Two demonstrations were held in 1979, one on Memorial Day and the other on Labor Day.

Although quite popular, not everyone enjoyed the branding demonstrations. Superintendent Heyder observed the demonstration firsthand on May 20, 1973, and later wrote to Tracy:

Personally, the branding, castration and dehorning, marking of the ears, and the general handling of the stock, which was quite rough, I found repulsive. I do realize it is a way of life, which is required in the cattle business. It is an historic fact that these methods were employed by the cattle industry and will continue. From a Park Manager's standpoint, the brandings provide an individual with an excellent education concerning the operation of the cattle industry. And I am quite sure that if individuals were polled who visit the Park on a day of such an event, we might well find many in favor and many in disfavor. But, when weighing all the facts, it is a good living history presentation. [2183]

Heyder recommended that the demonstration be continued but forbade the VIPs to allow youngsters to mount and ride the animals. He had observed one boy thrown off a young steer. "This cannot be tolerated at any further brandings," he wrote. [2184] Fearful of tort claims against the Park Service, he advised Tracy to make one of the monument's employees (either Rick Wilt or Mel Heaton) a safety officer to ensure that only VIPs entered the corral during demonstrations. He also recommended that an operational plan be developed for the branding demonstration.

Domestic Arts Demonstrations

During the 1970s, costumed female VIPs primarily participated in demonstrations of quilting, baking, soap and candle making, spinning, weaving, and churning. (CETA girls also participated in these demonstrations.) Female VIPs were paid $1.60 per hour for the quilting program and the monument paid for the cost of materials for their dresses ($10 each). The cost for the women's quilting program in 1972 was $450. [2185]

Zion Natural History Association

The Zion Natural History Association (ZNHA) had operated a branch sales outlet at Pipe Spring in the old visitor contact station. With the larger space rented by the Park Service in its new visitor center, the association realized a 300 percent increase in sales in 1973 over 1972. In 1973 the association provided funds for the dedication program for the visitor center and for the purchase of books for the library. It also published a Pipe Spring poster that sold well. During 1974, ZNHA sales increased by another 45 percent. The association contributed $1,147 to the monument that year for library books and supplies for the interpretive program. Sales continued to rise in 1975 by 58 percent. In addition to books, slides, and postcards, the association sold quilts, an expensive item that boosted revenue. [2186] That year the ZNHA donated $680 to the monument for library books and to purchase a wagon to be used in the living history program and 1976 wagon trek. Association sales again showed a 25 percent increase in 1976 and the ZNHA contributed $1,040 to the monument. The association donated $943 to the monument in 1977. That year its sales in the visitor center showed a slight decrease over the previous year. In 1978 sales once again showed a slight decline. That year the ZNHA donated $2,200, $1,571 of which was used for the purchase of a reproduction cheese vat for the fort. Sales in 1979 showed an 11 percent increase over 1978. The association gave $859 that year to the monument for its interpretive program, the museum, and library.

Personnel

Administrative changes at the superintendent level at Pipe Spring were mentioned under "Monument Administration." This section summarizes changes in all other staff from 1971 to early 1979, both seasonal and permanent.

Tracy did not have a permanent park historian until Richard K. Wilt was hired in late October 1972. [2187] Wilt remained at Pipe Spring for two years before taking a promotional transfer to Badlands National Park in November 1974. His position was vacant until the hiring of Glenn O. Clark, GS-09, on March 30, 1975. (Clark took a lateral transfer from Lassen National Park.) In late July 1977, Glenn Clark took a promotional transfer to Virgin Islands National Park. Clark's park historian position was abolished that year and a new position of park technician (interpretation) was established at the GS-06/07 level. Fred Banks, Jr., formerly at the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historic Park, was hired to fill the position on February 26, 1978.

In 1973 Park Technician Konda Button (clerk/typist), originally hired under Operation Mainstream, was appointed to a career-conditional position at the monument. She later married and resigned her position on May 16, 1974. A permanent park technician position was authorized in 1974, but was occupied by Joe Bolander on a subject-to-furlough basis due to hiring restrictions imposed in early 1974. A new park technician position (clerk/typist) was created in 1976, filled by Paul Happel, GS-04, on August 17, 1976. He transferred to the monument from the Soil Conservation Service in King City, California. Happel stayed only one year, transferring to Point Reyes National Seashore in late September, 1977. On January 15, 1978, Park Aid Nora Heaton (widow of former monument employee Kelly Heaton and mother of Mel Heaton) was hired as a park technician (clerk/typist), GS-03/04. She was upgraded from a GS-03/3 to GS-04/2 on August 29, 1978.

Seasonal park aids hired during the 1970s included Nora Heaton, Yvonne Heaton, Adeline Johnson, Lisa Heaton, Clorene Hoyt, Carla Esplin (all local whites), and Lori Jake (Kaibab Paiute). Two Kaibab Paiute women, Leta Segmiller and Elva Drye, were hired to demonstrate Indian crafts during the summer of 1976. This one-time project was made possible with bicentennial funding. (See "Interpretation" section.)

Laborers hired on a seasonal basis during the 1970s included David Johnson and Alfred Drye (1970); Elwin John (1974-1976); Carlos Bulletts (1977-1978 and possibly 1979). Drye, John, and Bulletts are Kaibab Paiute men. In 1979 the monument hired its first female laborer; her name could not be located.

The monument lost two very valuable "old-timers" from the monument during the 1970s. After working 12 years at Pipe Spring, Joe Bolander resigned on January 31, 1976. His departure was a serious loss to the interpretive program. Particularly during the 1970s, Bolander was the object of much high praise by visitors and Park Service officials alike. Another valued employee, Mel Heaton, resigned after nearly 13 years, on May 12, 1979, to go into business for himself. [2188] His maintenance position was then abolished.

Dale Scheier was hired at the GS-05 level into Joe Bolander's old park technician position on June 6, 1976. Scheier was formerly at Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in Three Rivers, California. In addition to overseeing monument maintenance, Scheier was an excellent amateur photographer. During his years at Pipe Spring, he created an impressive collection of photographs and slides related to the monument's living history program. On July 16, 1978, Scheier was given a promotion to a GS-06 level.

Permanent monument personnel received training to improve their job skills during the 1970s, some on their own time. Details on specific trainings completed by personnel are reported in the Superintendent's Annual Reports for 1972-1979.

Interpretation

Programs, 1970-1974

The interpretive theme of the 1970s concentrated on portraying both the Mormon "pioneer" era and Pipe Spring as an operating cattle ranch, circa 1870-1880. The program had a strong basis on history and the local environment, telling the story of human occupation of a desert ecosystem. Guided tours were enhanced by costumed guides and a wide variety of demonstrations including cooking, sewing, weaving, butter churning, and other historically appropriate domestic arts. In general, the living history program was active from May through September, the months when the monument received most of its visitors. As it had in the late 1960s, the monument's living history program depended very heavily on the participation of young NYC and CETA workers and on older VIPs. By 1972 it was reported that 90 percent of interpretation was dependent on NYC and VIP personnel. [2189] Public branding demonstrations were completely reliant on male volunteers and attracted much attention. The living history program continued to be very popular with visitors and many favorable comments were received during the 1970s.

The quilting demonstration was also quite popular with the public. Both traditional and original designs were used for making quilts. The Zion Natural History Association purchased supplies for making the quilts then later displayed and sold most of the finished pieces in the visitor center's gift shop. The quilts were pieced on a treadle sewing machine on site, then hand-quilted. Two quilts made as part of the monument's living history program - a bicentennial quilt depicting the fort and a star quilt - won blue ribbons at the Northern Coconino County Fair in September 1976 for workmanship and design. The star quilt was sold, but the bicentennial quilt, designed and partly sewn by Pam Clark (wife of Park Historian Glenn Clark), was made part of the monument's permanent collection. [2190] Those pictured in figure 131 are working on a double wedding ring quilt.

|

|

131. Quilting demonstration in the fort, 1977. From left to right: unidentified girl, Lisa Heaton, and Nora Heaton (Pipe Spring National Monument). |

The enhancement and expansion of the historic landscape was also part of the monument's interpretive program. Vegetable gardens were planted each year and the fruit orchards were maintained. Horse-drawn equipment was used in agricultural activities. In the early 1970s, a cow and horse belonging to employee Mel Heaton were kept in the pasture and used as part of the interpretive program. [2191] Tending to and irrigating the monument's vegetation required much attention. As the number of available male NYC or CETA enrollees declined during the decade, maintaining the historic landscape put quite a strain on Heaton and one seasonal laborer.

In addition to the expansion of gardens and orchards that took place in the early 1970s, chickens, ducks, and geese had the run of the area and horses grazed on the fenced meadow. Even the native grass restoration project begun by Ray Geerdes in 1968 played a role in the interpretive program. The "Interpretation" section of the monument's 1971 draft Management Objectives describes how the landscape elements intertwined with living history demonstrations as a teaching tool:

The lower southwest section of the monument has been utilized as a native-grass restoration patch. The domestic demonstrations and the cattle-branding demonstrations both fit well into the environmental theme of proper use of the resources, historically and presently. Historically, it is possible to show the positive features of the Mormon pioneer resource use, such as communal use of water and resources and how these probably affected the land philosophy of John Wesley Powell. Positively, the combination of restoration of the native grass and the branding demonstration exert a strong influence on the local cattlemen to use the range resource so that the grass can be restored and optimum use of the range resources maintained. The large reservoir of good will created in the local cattle community, by public branding demonstrations and restorations of the 'living ranch' theme, has exerted a stronger environmental influence.

A combination of the interpretive theme and restoration of native grasses has, in effect, made the entire area - both interpretive and resource management-wise -an environmental study area. School children and others can be made graphically aware of the contrast of the emerging native grass area and the denuded appearance of the surrounding range when viewing both from the combination historic and nature trail over the Vermillion Cliff behind the fort. [2192]

The Zion Natural History Association contributed funds throughout the 1970s to enhance the monument's interpretive program. Their financial contributions are listed in Appendix VIII, "Monument's Administrative Budget."

The completion of the visitor center finally provided the monument with adequate space for an orientation exhibit that could be enjoyed by the visitor prior to their tour of the site. An exhibit plan was completed for the visitor center in December 1973 and was sent out for internal review in April 1974, along with audio texts for wayside exhibits. [2193] (Prior to then, the labels and text were reviewed and accepted by the Church historian in Salt Lake City.) Tracy and Deputy Regional Director Glen T. Bean requested a number of substantive changes. By the end of July, Harpers Ferry Center was ready to put the exhibit plan into production. In June 1975, Harpers Ferry staff completed and installed an exhibit in the visitor center lobby and 20 wayside exhibits along visitor walkways. It was acknowledged that while the waysides would intrude on the historic setting, this consideration was outweighed by their contribution to the visitor's experience. The visiting public favorably received the new exhibits, with the audio units contributing to their effectiveness. (A number of the museum exhibits are still in use today, while most waysides have been removed.)