|

Pipe Spring

Cultures at a Crossroads An Administrative History of Pipe Spring National Monument |

|

PART VIII:

THE COLD WAR ON THE ARIZONA STRIP

Introduction

The year 1951 quickly ended the peace and quiet of the early post-war years at Pipe Spring National Monument. Atomic weapons testing at the nearby Nevada Test Site, as well as activity associated with uranium and oil exploration and mining, signaled that a new era had arrived on the Arizona Strip. This chapter deals primarily with events transpiring in and around the monument during the period from January 1951 through December 1955. The highlights for these five years include the observable impacts of weapons testing and mineral exploration and mining; administrative changes at the Washington, regional, and monument levels; the monument's acquisition of a two-way radio (1951); stabilization work to the fort's balconies (1951), exterior painting of the fort (1952) and restoration of the spring room (1953); destruction of the barn/garage by fire (1951) and construction of a new utility building (1952-1953); acquisition of a pressure fire pump and accessories (1953); installation of a new generator and construction of its housing (1954); installation of new highway and park signage (1954-1955); and filming of the first movie at Pipe Spring (1955). The early 1950s also was a time when evidence was being gathered for an important legal case, Arizona v. California, in which the United States asserted claims to water in the mainstream of the Colorado River on behalf of five Indian reservations in Arizona, California, and Nevada. Outside the monument, perhaps the most memorable event among local residents was the Arizona law enforcement officials' raid on the polygamous settlement of Short Creek in July 1953. Finally, during this period Custodian Heaton acquired seasonal part-time help for the first time.

In addition to the Arizona v. California case, one other important historical event took place during the early 1950s that particularly impacted American Indians. On August 1, 1953, Congress passed the Termination Resolution, adopting a policy of discontinuing federal controls, restrictions, and benefits for Indians under federal jurisdiction. [1492] Between 1954 and 1960, federal services or trust supervision was withdrawn from 61 tribes or other Indian groups, until opposition caused a deceleration of the program. Many tribes and Indian organizations, such as the National Congress of American Indians, condemned termination, advocating instead self-determination and a review of federal policies. Depending on where they lived, Indian tribes were impacted differently by the Termination Resolution. While the Paiute in the state of Utah were officially terminated, bands of the Southern Paiute Nation living in Arizona and Nevada were not, although the threat of termination of their reservations loomed over these years.

Several important administrative changes took place in the Washington office, the regional office, and at Zion National Park during the early 1950s. On April 1, 1951, Arthur B. Demaray succeeded Newton Drury as Park Service director. He held that position only until early December when Conrad L. Wirth succeeded him on December 9, 1951. Wirth remained director until early 1964, overseeing the Park Service in the years leading up to and during a most important period in the agency's history known as Mission 66. At Zion National Park, Paul R. Franke succeeded Charles J. Smith as superintendent on June 1, 1952, and served in that position until the end of 1959. This was Franke's third and last time serving as Zion's superintendent. During 1953 the National Park Service reorganized, both at the national and regional levels. In addition to the pre-existing Division of Design and Construction, two new divisions were created: the Division of Interpretation and Division of Cooperative Activities. The four regional offices were delegated some authority previously exercised by the director. On March 1, 1955, Regional Director Minor R. Tillotson died. He was succeeded by Custodian Leonard Heaton's old friend from Southwestern Monuments, Hugh M. Miller, who remained in the position until late 1959.

Cold War Background

By the end of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union emerged as two superpowers, each championing opposing ideologies. A continuous pattern of confrontations was set into motion between the "Free World" and "Communist Bloc" that continued to feed on itself. The United States' first use of atomic weapons against the Japanese forever changed the nature of war, challenging later political leaders to keep conflict to conventional, pre-atomic levels. The resulting tension and political posturing between nations is known as the "Cold War." Its effects span three decades, by the reckoning of some historians. [1493] The foreign policy groundwork for the Cold War was laid between the end of World War II and 1952, by which time the United States was vigorously engaged in the above-ground testing of atomic weapons and in supporting the exploration for and mining of uranium sources. Both activities would have significant impact on parts of Utah and Arizona during the early 1950s, not only because of these states' physical proximity to and location downwind of the Nevada Test Site, but because areas within these and other southwestern states became the prime targets of uranium prospectors. The Nevada Test Site is located in south central Nevada, surrounded on three sides by Nellis Air Force Range. Its southern boundary is about 63 miles northwest of Las Vegas, Nevada.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, elected to office in 1952 and reelected in 1956, led the country during this period. While the early Cold War environment set the political stage for the Korean War, the communist "witch hunts" of the McCarthy era, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the war in Viet Nam, this chapter will only address ways in which its effects were experienced in the area of Pipe Spring National Monument during the 1950s. While these effects were arguably only tangential to the everyday management activities of Custodian Heaton, they provide a rather unsettling backdrop to his day-to-day activities, and to those of predominantly Mormon and Indian families in surrounding communities, which is unique to that particular place and time.

In the introduction to Carole Gallagher's American Ground Zero, The Secret Nuclear War, Keith Schneider wrote,

Minutes before the first light of dawn on January 27, 1951, an Air Force B-50 bomber banked left over the juniper and Joshua trees and dropped an atomic bomb on the desert west of Las Vegas. The flash of light awakened ranchers in northern Utah. The concussion shattered windows in Arizona. The radiation swept across America, contaminating the soils of Iowa and Indiana, the coastal bays of New England, and the snows of northern New York.

Thus began the most prodigiously reckless program of scientific experimentation in United States history. Over the next 12 years, the government's nuclear cold warriors detonated 126 atomic bombs into the atmosphere at the 1,350 square-mile Nevada Test Site. Each of the pink clouds that drifted across the flat mesas and forbidden valleys of the atomic proving grounds contained levels of radiation comparable to the amount released after the explosion in 1986 of the Soviet nuclear reactor at Chernobyl. [1494]

On April 6, 1953, an 11-kiloton atomic bomb nicknamed "Dixie" was dropped from a B-50 bomber onto Frenchman Flat, a dry lake bed at the Nevada Test Site. The drop was part of a secret mission, called "Operation Upshot-Knothole." [1495] When Utah sheepherders conducted their spring roundup that year, they found their ewes and lambs with unsightly burns, lesions in their nostrils and mouths, and so sick many could barely stand. At the lambing sheds, ranchers witnessed the births of spindly, pot-bellied lambs that lived only a few hours. Of the 14,000 sheep on the range east of the Nevada Test Site, roughly 4,500 died in May and June of 1953. Convinced that the losses were due to radiation from atomic tests, the ranchers filed suit in Federal District Court in Salt Lake City in 1955, seeking compensation from the federal government. They lost the suit in September 1956. [1496]

It was only in 1978, when President Jimmy Carter ordered the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to make public its operations records that the truth began to emerge about the costs of the country's defense and foreign policies during the Cold War's early years. In 1980, 24 years after the Utah ranchers lost their case, the House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce investigated the sheep deaths and concluded the AEC had engaged in a sophisticated scientific cover-up aimed at protecting its testing program. It is only with hindsight that we can now appreciate the grave dangers posed by the testing of atomic weapons in Nevada, particularly to the residents of Utah and Arizona. Representatives of the federal government told everyone that the tests posed no threat to their well being and many people believed them.

The above-ground atomic tests of the 1950s and early 1960s then, along with their more observable effects - tremendous noise, earth-shaking vibrations, unusual cloud formations, and weather changes - became objects of curiosity, something to be noticed or written about in one's daily journal, as well as a completely novel topic of conversation. During these years, Custodian Heaton gives us just a glimpse of what it must have been like to live on the Arizona Strip at that time through his faithful daily recording in the journal he kept for the monument. What is impossible to gauge is what (if any) level of fear or worry lay beneath the surface of Heaton's observations or those of others like him. Residents of the Arizona Strip went about their daily work of tending crops, minding sheep and cattle, and raising a new generation of children. Such testing would not end until 1963, when tests started being conducted underground.

Pipe Spring and Weapons Testing

On January 27, 1951, Leonard Heaton wrote in his journal, "At about 6:30 this morning I heard what I thought was two distant dynamite blasts or rocks rolling. Later while in Kanab and Orderville [I] learned of atomic bomb blast in Nevada at about that time, so believe it was atomic blasts." [1497] The next day, he reported,

Sunday, day off from work. Atomic flashes and blasts were seen and heard at Moccasin and Kanab this morning at about 7:00. Homes were reported as being shaken by the blasts at Moccasin. Carl W. Johnson reported seeing the flash of light Saturday morning at Pipe from the Atom Bomb. Cloudy and stormy looking. [1498]

Below are additional excerpts from Heaton's journal (HJ) and monthly reports which chronicle Heaton's experience of some of the weapons testing that was taking place to the west between 1951 and 1957:

Saw the flash of the atomic bomb and heard the blast this morning. Seems to have been the biggest yet. (HJ, February 6, 1951)

Heard the atomic explosion again this morning. Not so hard as last several, I guess. (HJ, November 5, 1951)

Some of the folks heard and felt the Atom Bomb this forenoon [a.m.]. (HJ, April 22, 1952)

The A bomb of April 22 was heard and felt here at the monument which shook the building considerable. Also the one of May 1st was heard and felt. (L. Heaton, monthly report, April 1952)

There were two light storms during the month and these came three days after the Atomic blast. It has been said the Atom bomb was the cause of the storms here. (L. Heaton, monthly report, March 1953)

Atom bomb set off this morning. Was felt rather hard too. The flash was very bright. It lit up the country like daylight. (HJ, June 4, 1953)

Felt the two atomic blasts set off in Nevada today at 6 a.m. and the other at 11 a.m. Rattled windows and doors. (HJ, March 29, 1955)

Heard the atomic blast this morning. The atom cloud seemed to go southeast today. Lots of jet trails in the sky. (HJ, October 7, 1957)]

About 4 p.m. on March 5, 1951, after at least three atomic bomb tests in Nevada, an earthquake occurred at Pipe Spring, "going from west to east," Heaton reported, rattling windows and dishes at the monument. Another earthquake was felt on February 16, 1953. While there may be no connection between the tremors and the testing, it must have added to the area's general climate of uneasiness, as Heaton and others had already linked sudden weather changes to the testing. Heaton does not expound in his journal on his thoughts or feelings (or those of his neighbors) about the weapons testing in Nevada. [1499] He only reports seeing or feeling its physical affects. The invisible affects would not manifest for some time, but could possibly be linked to an unusually high number of Fredonia children diagnosed with leukemia between 1963 and 1967. (See Part X.)

Uranium and Oil Exploration

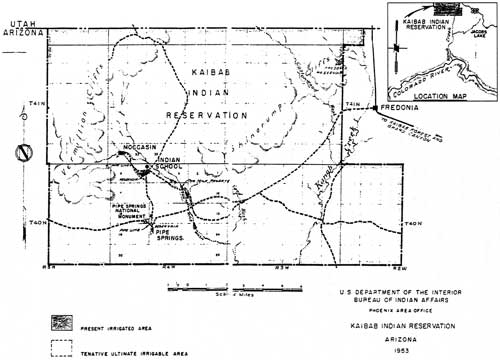

During the Cold War climate of the early 1950s, the Atomic Energy Commission encouraged the exploration and milling of uranium through a system of price supports and other incentives. This touched off a uranium boom, particularly on the Colorado Plateau. In southern Utah's Capitol Reef National Park, for example, the Department of the Interior attempted to prevent uranium mining and exploration, but the AEC cited national security as warranting full development of domestic uranium sources and pushed for prospecting in any potential uranium-bearing formations within public lands. In February 1952 a special use permit was signed between the AEC and the Park Service that opened Capitol Reef's lands to uranium miners. [1500] While no such action was taken at Pipe Spring National Monument, a considerable amount of exploration for uranium and oil took place on surrounding lands, including some on the Kaibab Indian Reservation.

During September 1952, Heaton began to report that a number of people camping on the monument were prospectors for oil and minerals: "Government men out looking for oil on Indian Reservation and will start drilling in a few weeks." [1501] That month 46 people camped for one or more nights at the monument, with a number of prospectors using the campgrounds as a base for their activities. It was reported at the Zion staff meeting in early November that drilling on the reservation by oil companies was to begin as soon as equipment could be set up. In March 1953 more oil prospectors were conducting oil exploration on the reservation.

Prospecting activity noticeably increased from June through October 1954, with concomitant use of the monument's campground. [1502] In early July Heaton reported,

There have also been a lot of prospectors going and coming through the monument hunting for that rare metal, Uranium. Instead of traveling with the lowly donkey (the Desert Nightingale) and pick and shovel, they have the high-powered gas wagons and geiger counters. Several hundred acres have been staked to the west and southwest of the monument. [1503]

In August 1954 Heaton reported, "More oil and uranium activities starting in the area." [1504] Heaton reported that mining and drilling had begun in the area "and the roads are kept busy with workmen driving to and from their work." [1505] In early September he wrote, "Quite a large outfit for core drill for uranium passed, going west. Report 40 or 60 300-foot holes are to be drilled." [1506] In October Heaton wrote, "Uranium drillers are here.

Pulled in last night. [They are] working some 10 miles to the west of the monument." [1507] There were no reports of rich finds. Several oil companies were trying to close leases on private lands so that they could begin drilling that winter. Heaton also reported a new user of Pipe Spring water: "Uranium mines are hauling quite a bit of water from the monument to use in their drilling operation." [1508] Area mining operations closed down over the winter of 1954-1955, except for a few claims staked by private individuals. In January 1955 Heaton reported, "The Mineral Engineering Company of Pueblo, Colorado is doing some core drilling for uranium on the cedar ridge 10 miles west of the monument. There was some drilling before but could not make any good test because of moisture and water in the ground at about 60 to 80 feet." [1509]

Monument Administration

Activities at the Nevada Test Site did not impact day-to-day activities at Pipe Spring National Monument, but they did give Heaton something out of the ordinary to report at Zion staff meetings. Heaton's wife and children continued to help give guide service and to assist with monument maintenance work during the early 1950s. After a January 1951 staff meeting at Zion, Heaton was given a new heater for his office in the fort. The heater, he later reported, "Keeps the room at a workable temperature, except draft on the floor." [1510] The next staff meeting he attended was on February 7, 1951, just one day shy of Heaton's 25th anniversary of working for the Park Service at Pipe Spring. Regional Director Tillotson sent Heaton a letter of commendation for his service.

The Rainmakers Cometh

Experiments in cloud seeding were carried out during the spring of 1951 in southern Utah parks and in the area of Pipe Spring National Monument. Superintendent Charles J. Smith described the activity in his monthly report for March to the director:

What could be very significant to the national parks of this area is the projected rainmaking venture, which has been instituted in southern Utah this spring. Seven counties in this area have contracted with a California firm to set up and operate ten stationary generators for cloud seeding from April 1, 1951 to April 1, 1952. The backers of the venture hope to double the annual rainfall in this part of the country and say that in many cases they even triple and quadruple it. If successful in bringing additional moisture to desert range lands, the 'cloud milkers' have visions of causing large amounts of snowfall to accumulate in the high mountains for use for power and irrigation. It is too early to hazard a guess as to what success this venture will meet with. Whether or not the venture is successful, we will watch it with great interest. In the event the project is successful, we can foresee the possibility of the most profound effects on our national parks. [1511]

A few days before the experiment was to begin, Heaton received a visit by two "rainmaker men" who left one of their machines in the area for testing. [1512] The Water Resource Development Company owned the machines, and its field representative was a Mr. Noble of Provo, Utah. The job of operating the machine at Pipe Spring, keeping records, and making reports was given to Heaton's son, Lowell, for which he was paid $1 per hour while operating the machine. Leonard Heaton commented, "Very simple thing. Burns charcoal with silver iodide in it." [1513] Apparently the "rainmaker men" would phone the monument with instructions to turn the machine on (it seems this was done when potential rain clouds could be seen approaching the area). Occasionally the men would stop by to check the generator and leave supplies for the machine.

Testing of the machine at Pipe Spring began in early April and continued into the summer. In April Heaton reported to Superintendent Smith that the silver iodide generator was run for 80 hours late in the month. He gave the invention credit for producing storms that generated 2.5 inches of rain during that time. No other weather affects were attributed to the machine in Heaton's later reports. On August 10, 1951, Heaton reported, "Mr. Noble, district supervisor for the rain making machines, was in and moved the generator from this area because of poor telephone service. Will likely be placed in Fredonia." [1514] In December of that year, Heaton reported to Zion that he received a call from Noble about putting the rain generator at the monument again. Then nothing more was written about the machine, the "rainmakers," or the outcome of their attempts to control the weather.

|

|

92. Leonard Heaton with "rainmaker machine," April 1951> (Photograph by Fred Fagergren, courtesy Zion National Park). |

This is Station KNKU20

In May 1951 Pipe Spring National Monument took a modest leap forward into the world of modern telecommunications with the acquisition of a two-way radio. [1515] Heaton got permission to get two, 50-foot pine poles from Kaibab Mountain to make a radio aerial. On May 11, two of Leonard Heaton's brothers, Grant and Kelly, helped the custodian erect the two aerial poles at the monument residence. On May 16, Heaton attended the Zion staff meeting, returning to the monument with the radio transmitter (Call KNKU20). The following day, Chief Ranger Fagergren and Chief Clerk Fred Novak came out to set up the radio at the monument and to inspect monument files. While the radio receiver worked, the two men had trouble getting the transmitter to work. Toward the end of May, two staff from Bryce Canyon National Park came out to fix the radio set, which turned out to be only a microphone problem. Heaton borrowed a microphone from the Moccasin Church to test out the set and managed to get the Chief Ranger at Zion on the radio that afternoon at 1:40 p.m. "Another milestone in communications at Pipe Spring National Monument," wrote Heaton in his journal, referencing Pipe Spring's 1871 telegraph office and later advances in communications. [1516] The radio enabled Heaton to communicate with park sites in southern Utah and northern Arizona.

The Monument Fire

A serious fire occurred at the monument on Saturday, July 7, 1951. On that date the 36 x 20-foot, wood-frame, combination barn/garage burned down. [1517] The fire was discovered about 5:00 p.m. by one of Heaton's children, who saw smoke and told Edna Heaton. Custodian Heaton was not on duty that day and was away; only Edna and two young children were home when the fire broke out. [1518] The burning building was located about 150 yards northeast of the residence, immediately adjacent to a cellar in which a large amount of fuel was stored for the electric generators. This added considerably to the situation's danger. Edna tried to call Moccasin for help but discovered the telephone wasn't working, which delayed getting help to the scene. While one of the children was left trying to make phone contact with Moccasin, Edna Heaton moved the government truck and then fought the fire with a carbon tetrachloride, "bomb type" extinguisher. The water tap near the building could not be used as it was too close to the flaming building. Edna fought the blaze for about 15 minutes before help arrived. "Help" at that moment consisted of eight youths under 16 years of age, who attempted to put out the fire with carbon tetrachloride and soda acid extinguishers. Edna Heaton prevented the youth from approaching too near the fire because of the danger of the fuel storage cellar igniting and exploding. About 15 minutes later, area ranchers arrived with a pressure pump and portable stock watering tank. While there was little left of the garage or its contents by that time, the men averted a potentially far worse disaster. The exposed roof rafters of the fuel storage cellar had ignited and the ranchers were able to extinguish the flames preventing much worse destruction at the monument.

Heaton returned home to the ruins of the fire that evening about 7:30 p.m. The custodian worked to put out the fire for another three hours, then kept a stream of water running on the smoldering ruins all night. The building was destroyed as well as its contents: four to five tons of hay, a chicken, a tractor and trailer, and many of the monument's hand tools. The following day, Heaton notified Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas by phone and reported the fire. The custodian thought the cause of the fire was spontaneous combustion from new bales of hay stored in the barn the previous Tuesday. On Monday, July 9, Chief Clerk Novak and a ranger came to the monument, took pictures of the fire damage, got a list of government and personal equipment lost in the fire, and interviewed Edna Heaton. Losses were later estimated at $1,100 for the building, $1,090 for Heaton's personal property, and $286.55 for loss of government property. [1519]

Heaton later cleaned up the mess from the monument's most destructive fire, hauling away five truckloads of burned materials. The fire also damaged about 200 feet of monument boundary fence, which Heaton replaced in August. In the fall he dug up about 300 feet of 3/4-inch pipeline that ran from the meadow to the garage site as it was no longer needed. In January 1957, using cinder blocks left over from the comfort station construction project, Heaton built four-foot high walls on the north and west sides of the old garage's rock floor "to have a place to park [the] truck and store things." [1520]

On August 30, 1951, Heaton answered a fire call in Moccasin at Chris Heaton's residence, taking with him nearly all the monument's fire fighting equipment (adequate to equip an eight-man crew). By the time he arrived, the fire was under control, he later reported.

Other Events, 1951-1952

In mid-June 1951, Heaton attended an Arizona Strip Community Association meeting where the decision was made to erect a large sign for the benefit of motorists on U.S. Highway 89. [1521] The sign was to depict the main roads and towns of the Arizona Strip. During August 1951, Regional Forester S. T. Carlson made his first visit to Pipe Spring National Monument. He later recommended to the regional office that early attention be given to installing a lightning protection system on the fort and to taking measures to protect the fort and residence from fire. (In this regard, his recommendations echoed those made by others in 1950.) He pointed out that while the monument had "copious amounts of water," there were no distribution lines or pressure system to provide for fire suppression. Carlson also recommended that monument trees be sprayed to control insects as an annual maintenance project. [1522] (Correspondence and later reports suggest an annual tree-spraying program was initiated in 1951.) In November and December 1951, as a fire protection measure, Heaton and four of his sons dug a trench and laid a pipeline to supply water to fire hydrants at the residence. It would still be some time before the fort received protection from lightning and fire.

Shortly after the July 9, 1951, monument fire, Heaton discovered someone had stolen a box of arrowheads from the Indian relic showcase. The thief had left the empty box in another room after removing the arrowheads. At this point, Heaton, was rather discouraged: "Makes a fellow pretty low to have things happened as they have to me the past month. First my girl getting hurt, fires, and things taken from the fort." [1523] Another theft was discovered by Heaton after the August 31, 1951, Winsor family reunion. The custodian reported that a small brown crockery jar recently donated by Maggie Heaton, Leonard's mother, was stolen from the museum during that event.

January 1952 was a difficult month for travel in the area, with not all problems attributable to local road conditions. On January 8, Leonard and Edna Heaton ran out of gas driving to Zion National Park for the staff meeting and a supper and party to be held afterward. (The fuel tank register didn't work on the truck.) The temperature was four degrees below zero. The couple finally arrived at the park at 10:00 a.m. A week later Heaton received a call from two regional office staff (one of whom was Regional Architect Kenneth M. Saunders) whose car was stuck in a snow bank on Kaibab Mountain. The two men were not bound for Pipe Spring at the time. The trip to assist them took Heaton three and one-half hours. While he didn't mind helping, what seemed to bother the custodian most at the time was that he had been waiting for some time for Saunders to come and inspect the work he had been doing on the fort. Money had been allotted to the monument ($500) for repairs to the fort, acquiring additional antique furnishings, and display cases. The monument also had an allotment of $700 to replace the burned-out garage with a new utility building. Heaton felt he needed some direction in planning the work that was to be accomplished with the money and was anxious for guidance that would enable him to plan out his work for the year. In the interim, Heaton completed some grounds-keeping chores over the winter, removing dead trees from around the fort ponds, digging up tree suckers from the meadow and campground, and thinning out willows growing on the banks of the meadow pond.

Superintendent Smith retired from his position at Zion National Park on April 30, 1952, and was succeeded by Paul R. Franke on June 1, 1952. After Heaton attended a staff meeting run by Franke, he reported, "Mr. Franke is making quite a change in our staff meeting procedures and it is not taking too well with the rest of the fellows. So it looks like our reports will be somewhat shorter when we get on to what he wants." [1524] Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas remained at Zion and Heaton usually dealt with him on monument issues.

During the summer of 1952, as in summers past, Edna Heaton was in charge of the monument during Heaton's absences from the site, often handling a considerable numbers of visitors. After more than 25 years of family members doing this pro gratis, either Edna and/or Leonard Heaton must have decided enough was enough. In July Heaton wrote in his journal, "Am going to see the director on the 21st about having her paid part-time employment for the two days I am away." [1525] Director Conrad L. Wirth and Assistant Director Ronald F. Lee visited Zion on July 21, when a party was held at the park. While Heaton attended the affair, it is unknown if he asked about possible employment for Edna Heaton at that time. During Heaton's absences, Edna continued providing year-round, unpaid guide service at the fort until the 1953 travel season.

In October 1952, when Heaton took two week's annual leave, Edna was in charge of the monument for the entire time. Again in early April (probably Easter weekend) Edna was left to oversee the fort and its visitors. A Fredonia community outing brought 212 people that Saturday, followed by another 340 people on Sunday. [1526] A few weeks later the decision was made that the family would spend the following summer at their farm in Alton, perhaps fueled by Edna's weariness with being left to manage the monument on her husband's days off or with the lack of privacy attendant with living on the monument. Of the decision, Heaton wrote in his journal, "Sure don't know what to do about the place this summer during my two days off from work with the family being away most of the summer. There will be no one at the monument to look after things during the day. Will work to try and get [a] hired laborer 2 days a week. Cost about $21 per week." [1527] The decision that the family move to Alton for the summer was made prior to Heaton obtaining Zion's permission to hire someone to fill in for him. This strongly suggests Edna (probably with Leonard's backing) may have in effect gone "on strike," serving Zion with notice they must find an alternate for Leonard Heaton on his days off.

On July 27, 1952, Franke paid an inspection visit to Pipe Spring, bringing his wife along. Franke discussed a number of topics with Heaton: getting park signage, trimming trees back so the fort was more visible, furnishing the fort, restocking the ponds, replanting orchards, and other work toward implementation of the monument's master plan. Franke was not pleased with the site proposed for the new utility building. Still Heaton seemed grateful for Franke's visit, his criticism, and direction. "It looks like I will get more attention from Franke than I got from Smith," he wrote in his journal. "Makes me feel that I am part of the organization rather than a necessary evil the park was putting up with and didn't want." [1528] This was a sentiment never expressed by Heaton when the monument was under the supervision of Southwestern Monuments. It seems he felt more like the "odd-man out" once Zion took over its administration.

In August 1952 Heaton confided in his journal that Franke's administrative style was rankling a few people: "Things don't set too well with Supt. Franke and the rest of the fellas. He seems to be too critical of things for them, being new in the place. He sees changes needed." [1529] In September he wrote in his journal, "The men are getting tired of the way Supt. Franke is running them. Don't have much to say," implying Franke had a rather dictatorial style. [1530] What was worse, Heaton complained that Franke's "short and snappy meetings" were getting longer and more tiresome. "Instead of an hour length they stretch out to two and one-quarter hours," he wrote. [1531] Long staff meetings (up to six hours) soon became the rule and Heaton began to dread them. In the days when cigarette smoking was in vogue, the meeting room was always filled with smoke. A non-smoker, Heaton frequently returned home with what he called a "sick headache" from these meetings. [1532] His journal has numerous references during the early 1950s like the following description of a staff meeting: "Took most all day. Seems like there is a lot of waste of time talking about little things, not of any value to most of the men." [1533]

Getting Power to the People

Arizona Strip communities continued to push for commercial power in their areas in the early 1950s. In September 1952 Heaton reported the Arizona Strip Community Association was pushing for Rural Electrification Administration (REA) to supply electricity to the communities of Moccasin, Fredonia, Short Creek, Jacob Lake and area ranchers (see Part VII for background on the REA). The group had decided to join the Kingman REA Corporation of Kingman, Arizona, in the hope of saving time and cutting through bureaucratic red tape involved in obtaining REA assistance. [1534] A meeting was held in Fredonia on January 5, 1953, to discuss the REA establishing a power line from GarKane Power Company's line at Mt. Carmel Junction to Arizona Strip communities. [1535] It was later reported that the REA program to the Arizona Strip hinged on the possibility of buying power from the Whiting Brothers Sawmill in Fredonia. Another community meeting in Fredonia held in February left Heaton optimistic about the area soon getting commercial power: "The prospects look good at this time," he later reported to Zion officials. [1536] But commercial power would be delayed years more.

Other Events, 1953-1955

An inspection of the boundary fence in February 1953 revealed that about 50 percent of the cedar boundary fence posts needed to be replaced due to deterioration. Except for a small segment replaced by Heaton after the 1951 fire, the monument's boundary fence was the same one installed during the winter of 1933-1934 under the Civil Works Administration program. Heaton made some repairs to the fence during October 1953.

Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson attended the Zion staff meeting on April 1, 1953. Heaton later reported, that Tolson "told us to obligate all the money as soon as we get authority to do so, then ask for more. It seems like the Service still hangs onto the New and Fair Deal Policies of the Democratic Party of spend and spend and ask for more." [1537] The monument was to benefit from that approach during the year. Two long-needed advances occurred during 1953 at the monument. That summer the monument received a new fire pump, reel, and fire hose. [1538] Heaton constructed a housing for the pump near the fort ponds in July. Finally the fort had fire protection. Heaton quickly discovered the new pressure pump was a great aid to him in cleaning out clogged pipelines and trash-filled cattle guards (rather creative uses of the system, but ones that fire protection rangers later frowned on). In 1955 the monument's carbon tetrachloride extinguishers were replaced with six new carbon dioxide fire extinguishers.

The other important expenditure of funds in 1953 was for hiring a laborer for the monument. On May 1, 1953, Heaton to attended a marathon five and one-half hour staff meeting at Zion. Edna Heaton was left in charge at the monument, tending to 225 students from Short Creek and Fredonia schools on a May Day outing. Heaton came home with welcome news: Zion gave him permission to hire a seasonal, part-time laborer on the two days a week he was off-duty. Edna and the children moved to Alton for the summer three days later. The laborer was Leonard Heaton's youngest brother, Melvin Kelsey ("Kelly") Heaton, who began work on May 14, 1953. During the summer Leonard Heaton worked Friday through Tuesday. Kelly Heaton worked Wednesday and Thursday. In the fall, when Leonard Heaton's tour of duty reverted back to Monday through Friday and Edna and the children returned to the monument, the laborer was let go. From about October to May, the fort was officially closed on Saturday and Sunday, but Heaton reported "most of the time someone is at the monument and can let people in." [1539] (That "someone" of course was Edna Heaton who continued to fill-in for the custodian during the off-season until 1957.) Word also arrived at the monument in June 1953 that Heaton was to get a pay raise to $1.73 an hour. [1540] That was good news, particularly since the rent for his quarters was raised a few weeks later to $17.50 per pay period. For the increase, Heaton would get a new heater and electric bills would be included. Zion officials promised several other improvements. Still, with the rent increase, Heaton wrote in his journal, "I am not much better off than before the raise." [1541]

Assistant Director Ronald F. Lee visited the monument on July 13, 1953, accompanied by Superintendent Franke. Lee was perturbed about the lack of monument signs at Pipe Spring, there being no visible indication that it was a national monument. Otherwise, Lee was impressed with the area and with Heaton's operation of the historic site. [1542] In the fall the Arizona Strip Community Association echoed Lee's request for monument signage at Fredonia, at the junction of the road to Hack Canyon (to the south on the Arizona Strip), and at the monument so people could find their way to the site. The lack of signage at the monument and at highway junctions had long been an identified need. Sign plans had been requested from the regional office but had not been received. In March 1954 Heaton called on Arizona State Highway Department officials to request directional signage to the monument be placed at the junction of State Highway 40 and U.S. Highway 89 in Fredonia. They agreed to this request and the new sign was placed in the summer of 1954. Finally in February 1956, new directional signs were received from Zion to replace the deteriorated wooden signs made in 1939 and 1940. These were placed along paths and in the campground area in March. New informational signs were installed in April. The installation of the large entrance sign delivered from Zion was delayed until Heaton found someone to help him erect it.

Kelly Heaton's appointment ended by mid-July 1953, leaving Heaton again without guide help until his family returned from the Alton farm. In mid-August he wrote, "There are a lot of people coming out to the monument during my day off that don't get to see inside the fort, but it sounds like I will not be able to hire anybody this year because of the economy drive in the government." [1543] In September Heaton asked Zion officials if Edna Heaton could be hired as a part-time employee while he was on annual leave. Correspondence suggests that the main objection officials had in hiring Heaton's wife was that she did not meet the qualifications of a laborer under which both Leonard and Kelly Heaton had been hired. A person was needed at the monument who could perform heavy physical maintenance work as well as provide guide service. Edna had only performed the latter work, so this may be one of the reasons Zion officials would not consider hiring her. The fear of charges of nepotism was probably not a factor in Zion's decision, for other close family members had been hired on a temporary basis to work at the monument. Unlike the wartime years, the Park Service during the post-war era generally considered hiring women only for clerical positions.

Other than Heaton's guided tour, the primary source of information about Pipe Spring available to visitors at the monument was a Park Service brochure. Heaton ran out of monument brochures during the summer of 1953. In May Zion officials asked for a reprinting of 10,000 copies but asked the regional historian to revise the brochure. There was some debate over the format and content, which held up its republication. Meanwhile, Heaton sold some reprint leaflets that were available from Southwestern Monuments for 10 cents each. The monument leaflet was reprinted in 1954, reduced from a four-page to two-page format. [1544]

Events of late July 1953 serve as a vivid reminder of the northern Arizona's Mormon 19th-century legacy of polygamy, which survived into the 20th century and, no doubt, will continue to be practiced by some into the 21st century. [1545] On Sunday July 26, at about 3:00 a.m., under orders of Arizona's Governor Howard Pyle, law officials conducted a raid on the town of Short Creek, located 15 miles west of Pipe Spring. Many of its residents were living in polygamous households. [1546] Heaton wrote in his journal that day, "Very active day. Lots of cars going coming past the monument as the Arizona officers, about 100 strong. Went into Short Creek, Arizona and arrested every man, woman, and child. A number of charges of conspiracy and white slavery and other state charges. Some 50 men and women were held and taken to Kingman to await trial August 27. It is a very sorry mess to be handling." [1547] The next day, Heaton wrote, "A lot of cars going by the monument but not many stopping. [In] Short Creek more arresting." And on the 28th, "Quite a few visitors, also a lot of traffic to Short Creek." [1548] Heaton reported that state officials moved the children from Short Creek to Phoenix in four large buses. "I suppose [there were] 26 cars and buses in their caravan, by here at 4 p.m.," he wrote on August 1. [1549] Husbands and wives without responsibility for children were jailed and children were sent to foster homes, accompanied by their mothers. [1550]

The raid was headline news in Arizona papers, which continued to cover the story for some time; it received considerably less press coverage in Utah. Ultimately the polygamists plea-bargained, pleading guilt to a charge of conspiracy. On December 7, 1953, 26 accused polygamists were sentenced to one year's probation and released. [1551] The raid did little to alter the Short Creek families' commitment to the institution of plural marriage. The Short Creek raid and associated publicity temporarily boosted visitation figures to Pipe Spring National Monument. The event also played a part in the town changing its name to Colorado City in either 1962 or 1963. [1552] Short Creek straddled the Arizona-Utah border. The Arizona side was named Colorado City and the Utah side was named Hilldale; the latter incorporated on December 9, 1963.

The monument received another boost in visitation when in August 1953 Westways magazine published "Refuge at Pipe Spring," an article by Jay Ellis Ransom. Its author praised the monument's campground as "one of the finest overnight refuges for tired travelers in all western America. It includes a marvelous open-air, natural-rock swimming pool and a two-acre 'bowling green' of virgin grass, formerly the old parade ground fronting the fort." [1553] There is no historical evidence that the monument's grassy meadow to which this author refers was ever a military "parade ground," but such fanciful bits of information were not uncommon in magazine articles and reinforced the popular idea of the fort as a military garrison, a remote outpost against "hostiles," rather than as the Church's cattle ranch. Heaton said the photos and information in it were out-of- date but he thought the article increased the monument's visitation. [1554] In July 1954 a reporter and photographer from the Arizona Republic newspaper visited the monument.

In January 1954 Heaton got the impression from reading circulating correspondence that officials were discussing the possibility of turning the monument over to Arizona State Parks or abandoning it altogether. [1555] Unrelated to that, during that month he began changing his official records over to a new filing system. "Looks like it will take me all summer to get them changed over," he reported in late March. In his monthly report for January, Heaton called Zion officials' attention to the fact that February 8, 1955, marked his 30th anniversary at Pipe Spring National Monument. He wrote, "During that time there have been no serious injuries to monument visitors. No one lost. Very little vandalism has taken place to mar the historic features of the monument." [1556] Actually, Heaton was a year off - 1955 marked only his 29th year at Pipe Spring. (Heaton was already thinking about retirement and perhaps was a little over-anxious to see the years fly by.)

Zion officials planned to hire Kelly Heaton to take over on Leonard Heaton's days off in May 1954, but Kelly became ill and was hospitalized at the time. [1557] Until they made their summer move to Alton on May 18, the family filled in at the monument. Heaton was able to get Zion officials to let him hire his son Sherwin on his days off until Kelly Heaton was released from the hospital. Sherwin ended up with the job for the entire summer. [1558] After the family returned from Alton on August 31, Edna once again took over the job, covering for Custodian Heaton while he took two weeks' annual leave that fall. Even on his days off, if he was on the monument, Leonard Heaton would often give tours of the fort. He wrote in his journal that September, "Just can't turn anyone away that calls at the house to be shown the fort." [1559]

In May 1955 Zion told Heaton that he could hire a seasonal laborer for up to 30 days for the rest of the fiscal year. He hired Sherwin that month but his son soon quit to take a full-time summer job. Then in June, Heaton's son Lowell took over. He also quit a few weeks later to accept a permanent job at the Grand Canyon. On June 21, Heaton hired Robin Grant Brown as laborer. Funds allowed him to keep Brown working five days a week for the summer season. This allowed Heaton to get a lot more projects completed that summer. In June all the monument trees were pruned and the west end of the west pond's rock wall was rebuilt.

During the second week of August 1955, several men inspected the monument to see if it would be suitable to film an Indian scene for the popular television program, "The Lone Ranger." Movie makers were also interested in the fort as a setting. On August 25, 1955, Heaton reported,

The Bel Air Movie Company came in about 6:30 a.m. today to start filming part of the western picture, 'Frontier Scout.' [1560] There was two large trucks of equipment, several smaller ones and under the direction of Howard W. Kock. Started filming by 8:30 a.m. There was a cast of about 24 whites and Indians. Filming [was] done in the courtyard and east side. There was also a number of visitors and local people coming to see the filming. Better than 125 people here. [1561]

On August 26, Heaton wrote,

More filming of horses and Indian fights around the outside of the fort. The filming completed and all property moved out by 3:30 p.m. Very little damage was sustained at the monument, just the trampling down of weeds and a few bushes and packed ground. No damage to building that I have been able to detect. The place was left pretty clean of litter. A lot better than I expected. I would not want to have any larger filming done here as it could do a lot of damage.... Filming these two days brought in more than 250 people. [1562]

So it was that in 1955 there finally was a "battle" between Indians and settlers at the old Pipe Spring fort! This would not be the last movie filmed at the monument.

Laborer Robin Brown's temporary position at the monument ended when the summer travel season was over. During September 1955, Heaton took several week's annual leave and was away from the monument the entire time. Edna Heaton and some of the children remained at the monument conducting visitors and school parties through the fort.

The "Neglect" of Pipe Spring National Monument

During May 1955, Heaton received a performance rating of "satisfactory" from Superintendent Franke. Heaton was disappointed, writing later in his journal, "He gave a satisfactory rating without seeing what I am doing at the monument for about a year. I wish they would come out more often." [1563] In late May 1955, Sherwin Heaton wrote to Superintendent John M. Davis, Southwestern Monuments, to request that the administration of Pipe Spring National Monument be transferred from Zion National Park back to Southwestern Monuments. On June 17, Davis responded to Heaton's letter. Judging from the response, it appears that Sherwin Heaton either insinuated or stated in his letter that the career of Custodian Leonard Heaton was not advancing as it should under Zion's administration. Davis replied that Leonard Heaton's advancement "is dependent entirely upon his capacities and his performance on the job" and that it made no difference who was overseeing his work. Davis added that he saw no need for the monument's supervision to be returned to Southwestern Monuments and would in fact advise against it, if it were proposed. [1564]

Judging by later events, Davis must have copied the correspondence to the regional office. At the time of this correspondence, Hugh M. Miller was serving as acting regional director in Santa Fe. Miller was concerned about what had led to Sherwin Heaton's letter. He copied it to Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas at Zion with a memo that stated,

I am, of course, convinced that Leonard Heaton knew nothing of this and I do not know who Sherwin is. Also I do not want to make any fuss about this matter, but I should like to have your comment and any information you can give us, particularly as to the sources of dissatisfaction of the administration of the monument by the Zion staff. [1565]

Thomas responded to Miller by memorandum to July 12, 1955:

I agree with you that Leonard had nothing to do directly with the correspondence of which you sent me copies.... There is, however, a growing feeling in the communities surrounding certain areas which we administer from this office that the areas are neglected. It is a problem with which we seem powerless to cope. The sad part of it is that there is considerable truth in the charges that the areas are neglected.... Inquiries reveal that the citizens of Kanab and Fredonia are dissatisfied with the treatment that Pipe Spring is receiving; Mr. Sherwin Heaton is a relative of Leonard's and [is] acting as spokesman for citizens of that area. [1566]

Thomas went on to say that Pipe Spring area residents knew that Capitol Reef National Monument had gone from no appropriation and an unpaid custodian in 1951 to having a GS-9 superintendent, seasonal ranger, and appropriation of $14,860 in 1955. Pipe Spring, on the other hand, had an annual appropriation of only $5,857, no seasonal help, and an ungraded employee as custodian. Moreover, Thomas said, Director Stephen T. Mather had promised Leonard Heaton at the time Heaton took over the monument that he would make every effort to get funding for a custodian's residence. "Ever since that time Leonard has been hoping to see that house," Thomas wrote. "Persistent justifications" by Zion officials for increased appropriations for Pipe Spring, Cedar Breaks, and Bryce Canyon parks "got nowhere," Thomas stated, inferring the problem was at the regional office level. Thomas made the recommendation that Pipe Spring be given a GS-7 superintendent, that funds for a six-month ranger historian and for seasonal laborers be provided, and that a residence or two and an administration building be built. "That would be a beginning," Thomas wrote. [1567]

All correspondence was copied to Superintendent Franke, a man with considerable historical perspective on the problem. Franke prepared an eight-page handwritten letter to Hugh Miller, which adds historical perspective to the problem. Most of it is quoted below:

I have read Art Thomas' reply to your inquiry as to what is wrong with the administration exercised by Zion over Pipe Spring National Monument. Frankly, there is nothing wrong that sensible personnel management and a little money couldn't cure readily. I heartily agree with Art in his recital of the difficulty of trying to pull constantly on our own bootstraps to get a little somewhere. In addition [to] the general picture which has been presented, I would like for you to get a little of the more intimate phases of the problem.

It develops into two distinct problems, each of which is an irritant of the other. Long festering, we have been unable to do anything about it.

The first problem is the Heatons. Some quarter of a century ago the NPS encouraged and took pride in the participation of family members of custodians in interpretive and protective activities. We bragged about the Honorable Custodians ___ and ___. Soon it was frowned upon and changes made everywhere (except Pipe Spring). Here through penury doling out of funds for management, we must continue through the years to demand from the employee the annual tribute of the pound of flesh. True, it is bloodless and paid to the government by family members (women and children) in the form of uncompensated services. Do you for one minute believe that such services are forever given willingly in the Spirit of everything for the National Park Service, but nothing for this family? All around them, progress has taken care of similar situations and loyal hard-working employees are reclassified or given a chance at more remunerative employment. Not so at Pipe Spring. The funds allotted don't even keep pace with wage board increases.

Leonard is a man with a pretty fair education, which includes several years at B.Y.U. Married early, he starts a big family early, in a locality where transportation, communication, and wages are probably the nation's worst. An injury cripples his hand so only one and part of another's fingers are usable. [1568] The 'Boss' [Pinkley] employs Leonard when Pipe Spring is removed from the Zion-Bryce-Grand Canyon travel route. The salary offered at the time is excellent when compared to what local cowboys and Indians were making. There is promise of a house, of help, and other improvements.

The employee is entered on duty and attacks his work with all the spirit we had in those days. He must do everything: build roads, ditches, irrigate, keep the pit toilets clean, dole out the water to the stockmen and Indians, clean campgrounds, maintain the buildings, and above all, interpret the historic fort and guide visitors. When in the midst of a messy job, his wife or one of the children took care of the interpretive and guide work. He only gets paid for 40 hours a week, yet his daily toils cover 12 hours and Saturdays and Sundays he stays on the job or assigns a member of the family. If by chance the food supply is so low that the head of the family must go to town for supplies, he must leave someone behind to watch the fort. He is still looking for that house, for some help, and the 40-hour week.

Amongst his duties is the monthly report. An ordeal, as he pounds away on the typewriter and the crippled hand misses the proper letters on the keyboard. The report passed around is considered 'cute,' 'unique,' and 'amusing.' He must continue to write it for the Brass in the National Park Service must be amused. The job, the man, the duties, become more demanding but the NPS each year in its allotments doles the edict: Pipe Springs National Monument shall not grow for we must keep the Heatons 'status quo.'

In spite of the great desire of our people to keep this area and its people as it was 25 years ago, the Heaton Family has grown, not only in numbers, but in stature. I doubt there is an employee in the National Parks like Leonard Heaton and family who have, without complaint, put up with poorer living conditions, yet have through the years contributed as much uncompensated time. The children have grown, attended school, graduated from high school, contributed their time and blood to the world conflicts and our Armed Services. Today the older ones have graduated from college, some are on missions, some are teaching, others in business, all fine members of their respective community. Dad continues to be a maintenance man doing the same chores, trying to blanket with his 40 paid hours the protection needs [which] are about 70 hours a week. He prepares the same report over which we smirk and laugh. Cute?

One can only surmise what the grown-up, educated children think of this Dad and the opportunities he passed up to join the higher paid laborers so much in demand in the growing communities of Fredonia and Kanab. Perhaps we get a look into the family thinking. Not a single youngster expressed a desire to go to work for the National Park Service. Why? True, we have occasionally found a few dollars by which we could hire for a few days one of the boys for laborer. Recently there is a more definite action. Some time ago the family negotiated for a large ranch up near Alton, Utah. This is just under Bryce Canyon. The family now goes there on Leonard's days off. No longer is a CWOP [Civilian Without Pay?] left to guard Pipe Springs and provide interpretive services to visitors. Perhaps the Region and Washington office will consider this as neglect on the part of the Heatons or this office.

You folks may ask what is wrong with Zion's supervision over Pipe Springs National Monument. My reply: I believe the Secretary's office could well take the Heaton case as a fine example of 'Personnel Mismanagement.'

Now what's wrong with the People of Fredonia? They have been waiting for us to do something for a long, long time. It's easy to jump at conclusions that Superintendents don't know what's going on. This one does, for with Leonard, I every once in a while attend meetings at Fredonia's Booster Club. I may sound optimistic to them at first, but they soon grow tired of the do-nothing attitude. We talked of signs. There is not one identification on the monument that this is a National Monument. The old sign at Fredonia, designed by Chuck Richey, is in ruins. I told the Fredonia people I would try and get some signs. We dragged the bottom of the purse and made them here at Zion. Fredonia donated a piece of ground to erect a sizable marker along U.S. 89. This [was] about two years ago, yet we haven't been able to finance their erection to this date. Meantime, some Washington officials come in [and] find living conditions so deplorable that they immediately allot a power plant and powerhouse. The original estimate and allotment was OK and we could have put the plant and supply lines in. However, as you recall, Region cut the Pipe Springs money, telling us we should be able to put this in at less cost than at Cedar Breaks. So last year and this year we use what little road money there is [to] try and complete this installation. The signs must wait and eyebrows raise among the Fredonia Boosters.

Time and again Fredonia people complain that visitors are directed out to the monument and no one is there or someone comes out of a deep ditch, plastered with mud, and volunteers to show them and explain the area. It's not an encouraging picture for Fredonia. What do we have? You look at the appropriation. We used to have some rehabilitation funds, which enabled us to meet Leonard's salary. Damned little rehabilitation was done and you all know it. With reorganization, the rehabilitation money is out and very little is added to the 200 accounts. The light plant costs more to run, supplies are increasing, and the margin between Leonard's salary and the necessary transportation, supplies, and repairs shrinks yearly, leaving constantly less for relief employment. The squeeze has continued for a quarter of a century.

We no longer have the CWOP outside the 40-hour week. We have by word, letter, and estimates urged that something be done. Promises galore, but negative results. We urged the control of tunnel traffic through Zion to divert more attention to fixing the Fredonia-Hurricane Road.

Enthusiastically endorsed by folks in the 'Strip' they worked to prove the need of this highway. However, the project died in birth. More and more huge trucks through Zion and less need of going via the Pipe Springs road. I wrote Senator Hayden that $700 annually would enable us to establish interpretive services at Pipe Spring and do much for increasing the travel and improve the economy of the community. 'It would also permit us to put on the payroll a young man recommended to him for employment.'

However, we caught no fish. What is wrong with the Service when it fails to give just a few dollars to small areas badly in need and then jumps on the Superintendent when someone pops off about the condition of the area? 'We in practice continue to give to him who has and take from him who has not.'

If S.W. Monuments can do something for Pipe Springs, for goodness sakes, let them do it... [1569]

Before he had received Franke's letter, Miller drafted a response to Art Thomas' letter of July 12, acknowledging the assistant superintendent's "good straight talk relative to the alleged neglect of maintenance and development of Pipe Spring." [1570] Miller, however, encouraged an attitude of looking toward future solutions rather than hand wringing over past omissions. While Miller knew it would be no consolation to local monument boosters, the logical explanation for the neglect of Pipe Spring was that other park areas simply had commanded preference. Visitation was always a factor when funds were being applied for and the very low visitation to Pipe Spring "can scarcely be overlooked as a factor," Miller pointed out. Where visitation was greatest, demands for funds were more urgent and more likely to be accorded attention first. Zion officials, of course, could increase the likelihood that Pipe Spring construction projects would be funded if they placed them higher up on their priority list (the Pipe Spring residence, for example, was listed as priority 40 on a list of 96 projects for the fiscal year 1957 construction program). The monument's preliminary estimates for that year included full-time positions for a superintendent and maintenance man. If a superintendent was hired, wrote Miller, he should be picked "as much for his manual dexterity as for this administrative ability." [1571]

Apparently Miller never sent this memorandum, for just after he drafted it he received Franke's letter of July 18. Taken aback by its condemnatory tone, Miller had the draft filed away and responded instead somewhat curtly,

I have read your longhand letter of July 18 with some dismay. My memorandum of June 28 about administration of Pipe Spring was intended to be merely a casual request for comment, which I could use in replying to the letter from Sherwin Heaton to John Davis.

I hope to talk the whole situation over with you to see just [what] we can should do now regardless of what the failures were or whose failures they were in the past. In the meantime, you might be getting your own ideas together, as to whether we are in fact ready to develop Pipe Spring; just how far we should go; and how we should staff it. Somehow I had failed to realize that Leonard Heaton is bitter or that we have neglected or imposed upon him. [1572]

Hugh Miller soon made an inspection visit to Pipe Spring with Art Thomas on August 31, 1955. He noted the need for lightning protection for the fort, a campground comfort station, and a custodian's residence. He inspected and approved the new utility shed, power plant, and fire pumper. With regard to personnel issues, Miller agreed to a three to four-month seasonal ranger historian position to help out with guide service during the busy summer months and to conduct historical research for use in an interpretive program. Miller also agreed that an effort should be made to create a GS-7 position and have Heaton put in it as acting superintendent. [1573] Zion and regional office officials set about trying to find a way to fund the two new positions. (An additional $950 was needed to hire a seasonal ranger historian and $220 more per year was required by Heaton's promotion. It appears that the regional office eventually "coughed up" the $1,170 so that the personnel changes could take effect in fiscal year 1957. [1574] ) Franke later pointed out to Miller that the ranger historian was needed not only to provide guide service and to conduct research, but also to provide security for the site when Heaton was not on duty. Since the highway passed through the monument, Franke thought Pipe Spring was particularly vulnerable to vandalism. [1575]

On December 15, 1955, after almost 30 years of service at Pipe Spring National Monument, Heaton received a promotion from maintenance man, ungraded, to acting superintendent, GS-7. Six months later, the monument hired its first seasonal ranger historian. During the next period of the monument's history - Mission 66 - Pipe Spring advocates would have much less cause to accuse the Park Service of neglecting the site.

Visitation

Visitation figures for Pipe Spring National Monument show a gradual increase during the early 1950s, rising from 2,104 in 1951 to 4,641 in 1955. [1576]

Easter weekends continued to be a busy time at Pipe Spring. Perhaps because weekends were his usual days off (except for the summer travel season), Heaton was away for the Easter weekend of March 24 and 25, 1951. "My children were in charge of the place," he later reported. Sons Lowell and Leonard P. provided guide service that Easter Sunday and looked after the crowd of 163 people who came for their holiday outing. [1577] Visitation during the Easter weekend of 1952 was high. Fredonia had a community outing at the monument on Saturday, April 12, with 215 attending. On Easter Sunday, another 84 visitors came. School outings that month brought the monthly total to 449 people, about one-fifth of the year's total. In 1953 the Easter weekend once again brought a large number of monument visitors. Warm weather and good road conditions probably contributed to the combined crowd of 552 who came that weekend. The Easter holiday (April 17 and 18) in 1954 brought 632 people to the monument. An all afternoon ball game was held in the meadow that Easter Sunday. On May 15, 1954, a single group of 350 people from St. George came to visit the monument.

|

|

93. Joseph Frank Winsor, age 88, taken August 31, 1951 (Photograph by Leonard Heaton, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 489). |

For the first time, Heaton got official permission from Zion to hire help for the Easter weekend of 1955. Heaton hired his son Sherwin to help with the expected crowds. That weekend (April 9 and 10) brought 721 visitors to the monument. The fort was open for people to come and go through at will; no guided tours were offered. At about 4:30 p.m. on Easter Sunday, a large cottonwood on the west side of the path between the ponds blew down, having been loosened the previous week by high winds. Fortunately, no injuries occurred. A few days later, Leonard and Edna Heaton worked two days cutting up the tree, hauling away the wood, and removing the stump.

During August 1951, two family reunions were held at the monument, the Parker family reunion on August 25 (61 people) and the Winsor family reunion on August 31 (65 people). Joseph Frank Winsor of Enterprise, Utah, the only living child of Bishop Anson P. Winsor, attended the latter gathering (see figure 93). Heaton pumped him for historical facts and reported later, "I got many good bits of information on things at the fort, as to how they built and uses made. Will get them written down ..." The reunion also appears to have prompted the donation of Bishop Winsor's 1848 muzzle-loading shotgun to the monument at this time or shortly thereafter. The evening after the Winsor reunion, Heaton hosted 80-90 Kanab Stake primary school girls who came to the monument for an evening supper. [1578]

Other Winsor family members visited the monument during the 1950s, including Ellis Hatch, (grandson of Bishop Winsor) and his wife on February 8, 1953, and other unidentified Winsor family members on August 21, 1953.

On June 2, 1951, the annual Arizona Strip Community Association barbecue was held at Pipe Spring National Monument. The event was attended by 310 people from Fredonia, Moccasin, Short Creek, Hurricane, Kingman, and LaVerkin. The crowd included some local officials, including Senator Clyde Bolenger of Mohave County, the mayor of Hurricane, Asa W. Judd, as well an Indian Service official, Superintendent Forrest R. Stone (Uintah Indian Reservation). "All seemed to have a good time and plenty to eat," Heaton reported. [1579]

A number of college student groups from California visited the monument during 1954. On April 11, 1954, Heaton had a party of 24 from Reedley College (Reedley, California) camp in the campground. On April 14, 38 cars and 110 students from Pasadena College arrived to camp at the monument. Also in 1954, a large group of fathers and sons of the Aaronic Priesthood, St. George Stake, visited the monument. The group was there for only three hours to picnic, but they brought 60 cars and 305 people. Heaton was challenged, he later wrote, in keeping the boys "from tearing the place down" since they were poorly supervised by their fathers. Some damage was done and a carpenter's plane was stolen. [1580]

Security of the historic buildings and their displays was always one of Custodian Heaton's concerns. On the weekend of September 9-11, 1954, Fredonia High School brought 50 students to the monument for an outing. Several of the boys broke the door in and others scaled the fort walls. Upon later inspection, Heaton could find none of the collection disturbed. "They should have asked to be shown in by some member of the family," Heaton later wrote. "We always have our trouble with the local people." [1581]

In March 1955 Heaton entertained a troop of 27 boy scouts from Cedar City, Utah, on a three-day outing to the monument. He spent time each day with the troop, joining them on Pipe Spring area field trips and giving them campfire talks. In late July, 186 primary school students from Kanab Stake had an evening outing at Pipe Spring. Heaton took part in a program for the children in which he assumed the role of an Indian chief. [1582]

On Labor Day weekend in 1955, the Heaton family held a family reunion on the monument. A total of 85 cars brought 521 members of the Heaton family for the event, described by Leonard Heaton as "an all day and evening affair." Heaton wrote in his journal that evening, "There were five Heaton brothers who settled in Orderville, Utah [in] 1879 and [these men] were very prominent in building this country." [1583]

Historic Buildings

The Fort

The primary project undertaken in 1951 was to reinforce the fort's two balconies. In February Regional Architect Kenneth M. ("Ken") Saunders and Assistant Superintendent Art Thomas inspected the fort and discussed with Heaton supporting the fort's balconies with angle iron and timbers. Stabilization plans for the balconies were dropped off by regional office staff on March 17, when Heaton was away. (He later complained in his journal, "I wish I would be notified when such men are coming, but maybe this monument doesn't rate notices." [1584] ) On April 10, Thomas inspected the proposed plans for repair work on the fort. Heaton began work on the balconies on May 3 and completed the job on June 26, 1951. [1585] Other work on the fort in 1951 included replacing broken windows, painting exterior woodwork, repairing balcony railings, and cleaning out the spring pipeline which, whenever it got clogged with tree roots, seemed to cause water to seep under the foundation of the northwest corner of the building.

During January 1952, Heaton removed loose plaster from several of the fort's rooms and prepared them for replastering. Freezing temperatures prevented him from completing the plastering work for a while. Heaton spent much of February and March painting the exterior woodwork and interior rooms of the fort. Light gray paint was used on most of the exterior wood except for the porch balusters, which were painted green. [1586] The porch railing was painted red. [1587]

In the spring of 1953, Heaton worked on restoring furnishings in the fort's spring room (milk and cheese racks and a cooling trough for milk) and replacing worn out flagstone in the room's floor. Heaton carved a trough out of a log, which he and Kelly Heaton installed in the spring room on June 23. [1588] On July 18 he turned the water back into the spring room which flowed through the wooden trough. The room was now restored "as it was when the fort was first built in 1870," Heaton observed proudly. [1589] He continued to work on furnishings for the room, working on the milk racks in November and December 1953. During the fall of 1953, a Kanab cabinetmaker, Mr. Pope, made reproduction doors for the fort's interior, based on an original door that Heaton took him. These were built of native pine. In November and December, Heaton replaced four doors in the fort that he had made 20 years earlier, which, like the fort gates, were not adequate as reproductions. As door frames were not square, he had to plane the doors to fit.

Other Rehabilitation Needs

In a March 10, 1953, memorandum to Regional Director Tillotson about monument rehabilitation needs, Superintendent Franke listed a number of projects with cost estimates. Among the list, he reported the southwest corner of the fort's lower building needed reinforcing. (A crack had developed from ground to roof and the wall leaned at the top about three inches.) Both the east and west cabin needed repointing and other minor work. The retaining walls around the fort ponds were crumbling and sloughing away and needed to be rebuilt, by far the most expensive of the proposed projects. Funds were also requested for purchasing period floor, wall, and bed coverings for the house museum, and for other period furnishings. Franke also listed the need for a new cesspool with septic tank and disposal trench for the Heatons' residence. [1590] Later reports by Heaton suggest that only the latter project was funded and completed during the early 1950s.

Monument Walkways

Some time prior to February 1951 the decision was made to convert the monument's gravel walkways to asphalt-surfaced walks. [1591] That month Heaton worked on drawing up plans and figures for the proposed walk improvements, which called for surfacing seven sections of walkways with "blacktop mulch." He completed some of this work in September and October, beginning first with paving the walkway between the fort and ponds, then paving the walk to the east cabin. The walkway project continued into 1952 and 1953, usually during the months of April and May. Heaton's sons and Kelly Heaton assisted with walkway resurfacing in 1953.

In May 1954 Heaton hired three Indians as laborers to help him resurface the walk to the west cabin, doing all the work by hand. [1592] The workers also helped him clean the monument ponds.

The Heaton Residence

Heaton continued to make modest improvements to his family's residence in February and March 1951 when he painted the old CCC infirmary with a coat of linseed oil, then two coats of white paint. Until that time, the structure had been unpainted. Then Heaton worked to prepare the ground in front of the house for grass seed, still trying year after year to get a lawn to grow. In April he painted the interior of the residence. During July through September 1951, Heaton laid wood floors in the residence.

|

|

94. Custodian's residence, April 10, 1951 (Photograph by C. A. Thomas, Pipe Spring National Monument, neg. 433). |

Even with improvements undertaken in 1948, the building still had its problems. An unsigned housing inspection report to Franke dated November 24, 1952, stated that the two biggest deficiencies in the custodian's quarters were lack of storage space and inadequate heating. Living so far away from stores, the family needed space to store food (much of it home-canned) and other supplies. The cook stove and a wood stove in the living room (both on the east end of the building) were the only sources of heat. The rock wool insulation installed in 1948 wasn't sufficient to keep the house warm nor could it compensate for the problem of ill-fitted windows and doors. Given the size of the Heaton family, the small size and number of rooms the building had was also highly inadequate.

During October 1953, Heaton constructed a new concrete-lined cesspool for the residence. It was located just west of the residence lawn and south of the old cellar. In March 1954 a windstorm blew off about 100 square feet of the residence's roof, requiring immediate repairs. In September 1954 Zion finally approved an old request of Heaton's and gave him a new oil heater, which he installed in the residence. The custodian soon discovered the heater was an expensive luxury. It used almost six gallons of oil per day, at a daily cost of $1.10. Heaton wrote in his journal, "This is going to cost us more than we can afford to pay so we may go back to the old coal and wood heater, unless we get another raise." [1593]

In January 1955 Heaton was told at a staff meeting to cut down on running the light plant for the residence as it was costing the government too much. He decided to turn it off at night after the family went to bed. He later remarked, "The stopping of the power plant is quite a job but very saving on fuel. By keeping the doors shut in the evening, the plant stays warm all night and [is] not too hard to start. Have to bleed the injection pump of air each time." [1594] In spite of his cost-cutting efforts, when he attended the February staff meeting, he was informed that $5 per month would be deducted from his wages for fuel oil and that a rent raise was anticipated.

Planning and Development