|

History of the Fremont National Forest

|

|

EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION

The Fremont National Forest is situated near the geographical center of the West Coast's ponderosa pine timber belt. The pine lands of northern California stretch to the south of the Fremont, and to the north stretch the pine forests of Oregon's and Washington's Cascade Mountains. The inland portions of Oregon and Washington and the Rocky Mountain states contain additional ponderosa lands, of course, but the "pine belt" of the eastern Cascades once offered a continuous stand of mature timber covering thousands of square miles from central California to the Canadian border.

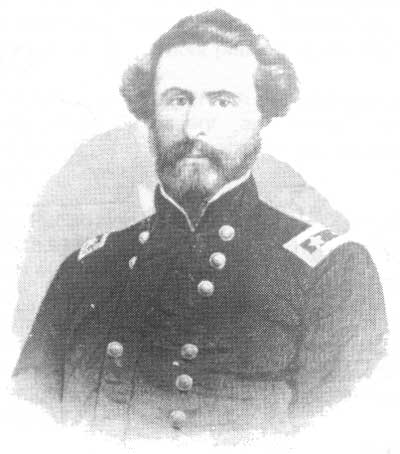

Captain John C. Fremont

The pine belt has figured into national history in several ways. In 1910, The Timberman magazine commented that the "timber belt of [West Coast pine]...constitutes the greatest body of standing pine timber now existing in America." The development of this immense resource involved some of the largest and most powerful industrial firms in the United States, including the Southern Pacific and Northern Pacific railways, the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company, the Long-Bell Lumber Company, Minnesota's Shevlin associates, and other lumber manufacturers.

The western pine industry began after the western fir and redwood industries had gotten their starts during the middle decades of the Nineteenth Century. Because the pine forests of the western states were located in inland areas out of the reach of navigable waters, the industry developed only after the transcontinental railroads made distant markets accessible. For central Oregon, rail transport was not available until the second decade of the Twentieth Century.

The development of the western pine industry was also influenced by the re-location of the lake states pine mills. Many of the pine lumber companies which had grown up in the Great Lakes region found themselves running short of timber as the Nineteenth Century drew to a close. While some of the lake states operators re-located in the fir-producing portions of the western states, the pine areas exercised a special attraction to others. The pine regions were less developed than the fir or redwood regions and the stumpage prices were correspondingly lower. Also, logging conditions in the western pine forests were closer to those prevailing in the midwestern forests. The trees were similar in size and stand density, the terrain was gentler than the coastal mountains, and the climate — with its cold winters and dry summers — offered an easier transition than the coastal rain forests.

The result was that large and well-financed midwestern firms like the Red River Lumber Company, Shevlin-Hixon, and Weyerhaeuser began buying extensive tracts of pine timber during the 1890s and the years after the turn of the century.

Oregon's Lake County — which contains much of the Fremont National Forest — attracted its share of this speculative attention during the 1890s and 1900s. Tracts of timber land were acquired from the Public Domain in Lake County (as elsewhere in the west) by expedients that skirted or openly flouted the law. Abuses of this kind led to the formation of the National Forest Reserve system and the protection of the Fremont lands.

The advent of railroads offers a convenient line of demarcation between pre-industrial lumbering in pine areas and full-blown industrial production.

Before railroads, lumber was manufactured on demand for local consumption; there was simply no way to get the product out of the country. After the railroad came, however, lumber could be cut steadily and sold to consumers as far away as the east coast. To offer a comparison between pre-industrial production and industrial production, we might consider the example provided by the Red River Lumber Company mill in Westwood, California. A pre-industrial water-powered sash mill such as those located in Lake or Klamath Counties might cut 100,000 board feet of lumber each year. The Red River mill — admittedly the largest western pine mill — at the peak of its production cut 800,000 board feet during an eight-hour shift.

In 1909, a branch of the Southern Pacific Railroad reached Klamath Falls, Oregon; in 1912, the narrow-gauge Nevada-California-Oregon railroad reached Lakeview; and in 1911, a branch of the Great Northern reached Bend, Oregon. The lumber companies followed the railroads to Bend and Klamath Falls within a year or two, and these towns were well on their way to becoming national centers of pine production by the time of World War I.

For Lakeview, however, the long-awaited railroad was a rather cruel joke. As a narrow-gauge line, the N-C-O used equipment that was incompatible with that of the broad-gauge lines. The result of this technological quirk was that lumber loaded into boxcars at Lakeview had to be unloaded and reloaded into broad-gauge cars at Alturas or Reno, where the N-C-O joined the national rail network. Since lumber was manufactured and sold on very narrow profit margins, mills located in Lakeview could not compete with mills located elsewhere. The extra handling and transportation costs were simply too much. As a result, Lakeview remained in a semi-industrialized state until 1928, when the Southern Pacific bought the N-C-O and converted it to broad-gauge track.

One part of the history of the Fremont National Forest is the story of American industrial development, but another part is the story of Lake County and the social and cultural development of one of America's last frontiers.

Euro-American settlement in the Goose Lake Valley did not really begin until the 1870s, well after most of the west was settled or at least settling. The ranchers and itinerant stockmen who first came to Lake County formed the community of Lakeview to wrest political power away from the rival community of Klamath Falls (then Linkville) located 100 miles to the west.

By 1880 Lakeview had a population of 270. Development proceeded steadily during the 1880s, and Lakeview was incorporated at the end of the decade. During the 1890s, Lakeview continued its pattern of slow growth as a service and retail center for the ranches of south central Oregon. Lakeview's isolation from the rest of Oregon became more pronounced as railroad and telegraph service connected other Oregon towns together. In his Illustrated History of Central Oregon, (1905), A.B. Shaver comments that Lakeview's location 150 miles from the nearest railroad gave the little town the "distinction...of being the farthest from a railroad of any county seat town in the United States."

The vast open ranges of Lake County attracted stockmen from throughout the western states and from Europe. Cattle and sheep ranches prospered. After the formation of the National Forest system from the Forest Reserves in 1905, the administration of grazing on forest grasslands became the central chore of the newly appointed Fremont staff.

Ethnic groups associated with the Lake County livestock business included the Irish and — to a lesser extent — the Basques. Both of the groups were involved in sheep raising. The Lake County Irish came from County Cork and other counties of western Ireland. In his leisurely and well-detailed account of the County Cork-Lakeview connection, From Shamrocks to Sagebrush, Robert Barry presents Lakeview as a comfortable, somewhat circumscribed community during the 1920s. Neighbors and relatives in the old country carried on their lives in the new country with a minimum of concern about the outside world. The most famous of all Lakeview Irish jokes makes this point very well. A Lakeview sheepherder from County Cork wired his nephew money for passage across the Atlantic and sent some avuncular advice to go with it: "Mikey, my boy, come straight to Lakeview; don't bother stopping in America at all."

On January 5, 1920, Dr. Bernard Daly, who was Lakeview's most prominent citizen, died en route to San Francisco. The town that Daly and his generation had built was essentially a market town for the ranches of the south central Oregon valleys. During the World War I years, the desert country of northern Lake County had filled with homesteaders, who added to the population base that Lakeview served.

Later in 1920, shortly after Dr. Daly's death, two "modern" lumber companies were incorporated in Lakeview. These were the Underwood Lumber Company, and the Lakeview Lumber and Box Company. All incorporators listed Lakeview as their residence. Still later in the same year, a "large Eastern firm," the Pennsylvania Door and Sash company, began purchasing timber land on Cottonwood Creek and acquired a mill site in Lakeview.

To the local journalists, this flurry of activity signaled Lakeview's coming of age. The new mills were committed to selling Lake County products throughout the nation. Both lumber companies were contemplating box factories, which had been the force behind Klamath Falls' rise to industrial prominence. The Pennsylvania Door and Sash company was an especially exciting venture since it was to be a remanufacturing plant. In operation, it would purchase lumber from local sawmills and manufacture the material into architectural components. The factory would give the county's lumber mills a local market for their product, and add value to that product before it was shipped off to national markets. So eager were the Lake County businessmen for the new ventures that they "subscribed" a sum of $3000.00 to buy the Pennsylvania company a mill site on the town's round-up grounds. The rich symbolism of selling the town's round-up grounds to provide a place for the new industry was too clear to be missed: livestock had shaped Lakeview's past, but timber would shape its future.

The 1920-1922 period was slow for the lumber business everywhere in the West. The nation was still absorbing the capacity that had built up to serve the World War I market and prices were off.

Lakeview's problems, however, had more to do with local concerns than with the regional picture. When the ailing N-C-O railroad tried to abandon its line in 1921, local residents perceived that the loss of a railroad would mean the end of the lumber business. Local feelings ran high when the Interstate Commerce Commission met to decide the matter. While their decision was fortunate for Lakeview, the whole episode did little to inspire confidence.

With the development of the lumber industry after 1920, Lakeview gradually changed from a market and livestock town to a mill town. Industry replaced commerce as a dominant economic force in the town. During the early years of the 1920s, the Lake County homesteaders began to "starve out" on their precarious desert claims. Many of these people migrated to Lakeview — as well as Klamath Falls and Bend — to join the pool of industrial labor.

Later, during the 1930s, the livestock business fell ill during the depression and died when the Taylor Grazing Act closed the open range. Stockmen, cowboys, and sheepherders looked for jobs in town.

Probably because of its narrow-gauge railroad service, Lakeview failed to attract the large national lumber firms that dominated the economies of other central Oregon towns. Such giants of the industry as Weyerhaeuser, Brooks-Scanlon, Long-Bell, and Shevlin-Hixon owned timber in Lake County, but they did not build mills in Lakeview. Corporate records filed with the Oregon Department of Commerce reveal that the firms that did build mills in Lakeview were financed locally, or at least with local partners. The net effect was that as Lakeview industrialized during the 1920s, it participated less in the "colonial economy" of the lumber industry than other central Oregon communities did. This is not to imply that all of the wealth extracted from nearby forests remained in Lakeview, but the slow, small-scale development of the lumber industry encouraged local participation and fostered economic health.

After 1928, lumber manufacturing began in earnest in Lakeview. Several new mills were built and the tempo of logging on private as well as public lands increased. In 1929, two of the largest Klamath Falls mills — Ewauna Box Company and Pelican Bay Lumber Company — began cutting timber near Fremont lands. The Oregon, California & Eastern railroad had been extended from Sprague River to Bly, and the long haul (80 miles) back to Klamath Falls presented no real problem.

In the economic and social chaos which followed 1929, Lakeview fared better than most lumber-dependent communities. Mills ran — at least sporadically — during the darkest years, and the industry began to show some real signs of life by 1933. By the fall of 1930, it had become apparent that the economy would not bounce back easily or quickly. Lake County production was off 35% from the previous year. Production revived slightly in the fall of 1930, with 90 carloads of lumber and 16 carloads of shook shipped out in November. The following year brought an increase in production to the 30 million board feet level and a new roster of mills. The 1933 season saw Crane Creek Lumber Company's Fandango mill open after a year's recess, and a new mill — the Buzard Lumber Company — open in the fall.

During the 1933 season, eleven Lake County mills cut 55 million board feet of lumber, a new record. Both the Timberman and the Examiner estimated the total number of workers employed by the industry at 800 — an encouraging number of jobs in a generally discouraging year.

By 1935, The Timberman was predicting the Lakeview district cut 75 to 80 million board feet. Lakeview had six large mills: Buzard-Burkhart Lumber Company, Underwood Lumber Company, the R.S. Adams mill, two DeArmond mills, and the Crooked Creek Lumber Company mill. Smaller mills included the A.L Edgerton mill, the Fields and Wilhelm mill, the Lake County Pine Lumber Company mill, and the Rohr Lumber Company mill. By the end of the 1935 season, all the Lake County mills were running, C.W. Woodcock planned to build a new mill in Lakeview, and the Lakeview Sash and Door Company was remanufacturing local lumber for shipment east. Total production for the year actually exceeded 80 million feet.

By the late 1930's, Bend's largest mill — Shevlin-Hixon — was preparing to cut timber in northern Lake County that it had purchased over thirty years before. In 1938, the Gilchrist Timber Company built a mill at Gilchrist, Oregon, to cut timber that they had purchased during the same speculative frenzy at the turn of the century. Finally, at the end of the 1930s, Weyerhaeuser began construction of its East Block railroad, an ambitious and nearly anachronistic project that would enable it to reach its timber holdings in western Lake County. Although Shevlin-Hixon, Gilchrist, and Weyerhaeuser cut their own timber, they also purchased Fremont National Forest sales, and they exchanged their cut-over lands into public ownership.

During the last four years of the decade, the potential that Lake County had offered for so long seemed closer than ever. Production edged toward 100 million board feet/year. The operating season lengthened, the work force stabilized, and entrepreneurs began new ventures with new confidence. Both mill workers and loggers were unionized by 1941. Lakeview presented a new industrial face. In July, 1936, The Timberman editor commented that "less than two decades ago" the talk in Lakeview was exclusively "beef cattle, range, and cow hands." All that had changed, and the cowboys had now "replaced their high-heeled boots and spurs with the spiked boots of the logger."

"When nearing Lakeview from the west, ... [lumber] plants make up a picture of well-founded industry. With the Southern Pacific tracks replacing the old narrow gauge road long trains of lumber products are seen going from these hills. Add to this the many logging trucks entering the city, [and] a ten-year absentee would hardly recognize the place."

In an similarly reflective article written in 1942, the West Coast Lumberman remarked on Lakeview's change.

"There are seven mills in or close to Lakeview. These start at one edge of town (where the railroad makes its entry) and follow along to the far end of town, making it a regular 'sawmill row' from one end of the city to another."

In summary, then, Lakeview's development during the 1871-1939 period includes two distinct phases. During the 1885-1928 period, Lakeview served the livestock industry of south central Oregon as a commercial center. The town provided goods and services for a market area of perhaps 20,000 square miles in south central Oregon and north eastern California. Beginning with the construction of a broad gauge railroad in 1928, Lakeview changed from a commercial town to an industrial town containing up to ten lumber mills and remanufacturing plants. As livestock declined during the 1930s, industry made a more substantial contribution to the local economy.

The effects of these historical patterns on the Fremont National Forest are clear in Bach's History. For the first three decades of its existence, the Fremont provided range and watershed for the livestock industry. Timber was not a management issue, since there were no timber sales of any consequence. Then, after 1928, when the broad gauge railroad reached Lakeview, the rich ponderosa stands began to attract outside attention. The Fremont's years of isolation drew to a close.

The pace of timber production on the Fremont grew through the 1930s until 1943, when it sold more logs than any other National Forest in the Pacific Northwest Region. The Fremont's production during this year exceeded even the coastal rainforests'. Record levels of production cannot be sustained in the slow-growing ponderosa forests, however, and the cutting rate has since slowed to a more reasonable level.

The history of the Fremont National Forest is intimately bound up with the development of south central Oregon. As the region has changed, the Forest's administrative and management policies have reflected those changes.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

fremont/history/intro.htm Last Updated: 01-Feb-2012 |