Senate Document 84

Message from the President of the United States Transmitting A Report of the Secretary of Agriculture in Relation to the Forests, Rivers, and Mountains of the Southern Appalachian Region

|

|

REPORT

ON THE

FORESTS AND FOREST CONDITIONS OF THE SOUTHERN

APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN REGION.

(continued)

|

Method and results of the examination.

|

THE FORESTS.

It is the forest covering of these great mountain

slopes— a covering that should never be removed—about which

interest centers in the present investigation. The results of this

examination during the past two years are given at length in a paper

published as Appendix A (p. 41). They are stated separately for each of

the larger river basins, following a somewhat general discussion of the

forest conditions in the region as they exist to-day and of how the

forests may be economically protected and improved under Government

control.

|

|

Forest maps.

|

These forests have been carefully studied and

classified, and over much the larger portion of the area their density

and distribution have been indicated on the excellent topographic maps

furnished for this purpose by the Department of the Interior. The length

of time required for engraving these detailed forest maps makes it

impossible to issue them as a part of the present report, but copies of

them in manuscript forum are meanwhile available for examination at the

Department of Agriculture and the Geological Survey. The distribution

of these forests and the approximate relative proportion of the

forest-covered and the cleared lands are indicated by the generalized

map (Pl. XII). The scattered cleared fields on the mountain slopes are

so small that it is impossible to indicate them on a map of this scale,

and hence only the larger clearings, mainly those along the valleys, are

shown.

Considering the forests of the region as a whole,

there is a striking uniformity about their general features, especially

in the valleys and along the lower slopes, and yet everywhere there is

variety. This fact is well illustrated by the list (on p. 93) of 137

species of trees and a still longer list of shrubs growing in this

mountain region.

PLATE XII. MAP OF THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN REGION.

(omitted from the online edition)

|

|

Variations in forests on southern and northern slopes.

|

The forests on the southeasterly slopes are usually

less striking, both in size of trees and density of growth, than those

on the northwest, and they are usually more damaged by forest fires,

because the slopes are steeper and are kept drier by their more direct

exposure to the sun. The neighboring forests on the northern and western

slopes and in the westerly facing coves exhibit a greater variety of

vegetation, a denser growth, and finer specimens of individual trees,

because they have not only greater moisture, but greater depth and

fertility of soil. Both are protected by the humus which covers the

surface and which contributes directly to the luxuriance of this growth.

It is in such situations that we find the best examples of the superb

hard-wood forests which abound in this region—the finest on the

continent. (See Pl. XIII.)

|

|

|

PLATE XIII. AN ORIGINAL SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN FOREST, TRANSYLVANIA

COUNTY, N. C. (See pp. 21-23, 45.) (Photographed by Scadin.)

|

|

|

Variations in forests due to elevation.

|

But the greatest variations in these mountain forests

are observed in connection with the differences in elevation. Thus along

the southern foothills of the Appalachians in Georgia one finds

occasionally scattered colonies of the loblolly and long-leaf pines,

trees which are characteristic of the South Atlantic and Gulf coast

region, intermingling with the typical hard-wood forests of the Piedmont

Plateau and of the lower mountain slopes. (See Pl. XIV.) At the eastern

foot of the Blue Ridge, in North Carolina, the typical flora of the

Piedmont Plateau abounds, and follows up the river gorges into the

mountain valleys, where it associates with more characteristically

Appalachian species. Thence up to the tops of the higher peaks there is

a constant succession of changes—an intermingling and overlapping

of the lower species with those which belong to greater elevations or

more northern latitudes.

|

|

|

PLATE XIV. MIXED HARD-WOOD AND PINE FOREST ON OCONALUFTY RIVER,

SWAIN COUNTY, N. C. (See p. 22.) On the lower mountain slopes and

ridges the pines are often mixed with hard woods. But whatever

the nature of the trees, the frequent fires are destroying the

undergrowth and humus and thinning out the trees, thus diminishing

the commercial value of the forest, facilitating the erosion of the

soil, and lessening its capacity for storing water.

|

|

|

PLATE XV. SPRUCE FORESTS AT HIGH ELEVATIONS; ON WHITETOP MOUNTAIN,

VIRGINIA. (See pp. 23, 47.) Seedlings of this black spruce abound

in the moss under the trees. These and the humus and the roots hold

the soils and help store the rains.

|

|

|

Forests on Mount Mitchell.

|

Thus in ascending any of the higher mountains, as

Mount Mitchell, which, with its elevation of 6,711 feet, is the loftiest

of them all, one may penetrate, in the rich and fertile coves about its

base, a forest of oaks, hickories, maples, chestnuts, and tulip poplars,

some of them large enough to be suggestive of the giant trees on the

Pacific coast. (See Pl. XLIV.) Higher up one rides through forests of

great hemlocks, chestnut oaks, beeches, and birches, and higher yet

through groves of spruce and balsam. Covering the soil between these

trees is a spongy mass of humus sometimes a foot and more in thickness,

and over this in turn a luxuriant growth of shrubs and flowers and

ferns. At last, as the top is reached, even the balsams become dwarfed,

and there give place largely to clusters of rhododendron and patches of

grass fringed with flowers, many of them such as are commonly seen about

the hills and valleys of New England and southern Canada.

|

|

Seasons vary with elevation.

|

In such an ascent one passes through, as it were,

the changing of the seasons. Halfway up the slopes one may see, with

fruit just ripening, the shrubs and plants the matured fruit of which

was seen two or three weeks before on the Piedmont Plateau, 3,000 feet

below; while 3,000 feet higher up the same species have now just opened

wide their flowers. Fully a month divides the seasons above and below,

separated by this nearly 6,000 feet of altitude.

|

|

General forest conditions.

Unwise forest clearings for agriculture.

|

Remote from the railroads the forest on these

mountains is generally unbroken from the tops of ridge and peak down to

the brook in the valley below, and to-day it is in much the same

condition as for centuries past. (See Pl. XVII.) In the more settled

portions of the region, however, a different picture presents itself.

Along the narrow mountain valleys are the cultivated fields about the

settlements, where they ought to be. When the valleys were practically

all cleared the increasing demands for lands to cultivate led to

clearings successively higher and higher up the mountain slopes, with a

pitch of 20 and 30 and even 40 degrees. From some of the peaks one may

count these cleared mountain-side patches by the score. They have

multiplied the more rapidly because their fertility is short lived,

limited to two, three, or five crops at most. They are cleared,

cultivated, and abandoned in rapid succession. Out of twenty such

cleared fields, perhaps two or three are in corn, planted between the

recently girdled trees; one or two may be in grain; two or four in

grass, and the remainder—more than half of them—in various

stages of abandonment and ruin, perhaps even before the deadened trees

have fallen to the ground. (See Pl. XVIII.)

|

|

|

PLATE XVI. THE TOPS OF THE BLACK MOUNTAINS. (Julius Bien & Co., N.Y.) (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

PLATE XVII. PANORAMA SHOWING THE UNBROKEN FOREST OF THE GREAT SMOKY

MOUNTAINS; FROM ANDREWS "BALD," SWAIN COUNTY, N. C. (See pp. 23, 53). (click on image for a PDF version)

|

|

|

PLATE XVIII. FOREST CLEARINGS FOR FARMING ON THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN

MOUNTAINS. (See pp. 26, 57.) Already one-fourth of the total area of

these mountain lands has been cleared; and additional areas are being

cleared, cultivated, and abandoned in rapid succession, higher and higher

up the mountain slopes.

|

|

|

Lumbering operations.

|

The lumberman attacked this forest several decades

ago when he began to penetrate it in search of the rarer and more

valuable trees, such as the walnut and cherry. Later, as the railroads

entered the region to some extent, he added to his list of trees for

cutting the mountain birch, locust, and tulip poplar, and successively

other valuable species. During the past few years he has cut everything

merchantable. He is now beginning to extend his operations to

considerable distances beyond the main lines of transportation by the

construction of tramways and even cheap, short railways. Meanwhile his

search for the more valuable trees has extended in advance to most of

the more remote mountain coves.

|

|

Damages from lumbering operations.

|

In these operations there has naturally been no

thought for the future. Trees have been cut so as to fall along the

line of least resistance regardless of what they crush. Their tops and

branches, instead of being piled in such way and burned at such time as

would do the least harm, are left scattered among the adjacent growth to

burn when driest, and thus destroy or injure everything within reach.

The home and permanent interests of the lumberman are generally in

another State or region, and his interest in these mountains begins and

ends with the hope of profit. There is, however, no evidence that the

native lumberman has in the past exhibited any different spirit.

|

|

Destructive work of forest fires.

Injuries resulting from the burning of the humus.

|

Forest fires have been one of the great curses of

this country. From the days of Indian occupation down to the present

time these Appalachian Mountain forests have been swept through by

fires. Some of these have preceded the lumberman, others have

accompanied him, and still others have followed in his wake, and the

last have been far more destructive because of the tops and other

rubbish which he has left behind him scattered among the remaining

growth. (See Pl. L b). The aggregate damage from these fires is

great. Over some limited areas they have entirely destroyed the forests.

Everywhere on the southward slopes the damages have exceeded those on

slopes toward the north or west. Trees have been burned near the roots,

making their bases defective (see Pl. XLVII); the young growth has been

burned down (see Pl. XLVI); the grasses and other wild forage plants

have been temporarily exterminated, so that instead of pasturage being

improved, as some have believed it would be, in the end it has been

seriously damaged. This destruction of the humus has always resulted

seriously both to the forests and to the soils. In some cases, where the

forests covering the steep, rocky slopes were thin, the loss of the

humus has resulted in the washing and leaching away of the soils to such

an extent as to destroy the forests entirely; and in all cases where the

humus is thus removed the work of land erosion among the trees goes on

as surely as though the forest itself were gone, though of course the

process is far less rapid. Furthermore, the storage of water (in soils

from which this humus has been removed) is far less perfect than in the

original perfect forest.

|

|

Imperative need of new forest policy.

|

The rapid rate at which these lumbering operations

have extended during the past few years and the still more rapid rate at

which they are being extended at the present time, considered in

connection with the destructive work of the fires and the clearing for

agriculture, indicates that within less than a decade every mountain

cove will have been invaded and robbed of its finest timber, and the

last of the remnants of these grand primeval Appalachian forests will

have been destroyed. Hence the very possibility of securing a forest

reserve such as now contemplated is a possibility of the present, not of

the future. This great activity indicates, furthermore, in the most

striking way possible, the growing anxiety as to the future supply of

hard-wood timber. And indeed the time is now at hand when the great

interests involved make it imperative that the Government take hold of

this problem and inaugurate here in these great broadleaved forests of

the East a new conservative forest policy, as it is already doing for

the pine forests of the West.

|

|

|

PLATE XIX. STONE MOUNTAIN, NEAR ATLANTA, GA. (See p. 26.) The ax and

fire have removed the forest; and the heavy rains have removed the soil

which once covered the larger part of this rocky knob.

|

|

|

FOREST CLEARING AND AGRICULTURE IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS.

Ordinary farming on these mountain slopes can not

exist permanently and should never exist at all. As stated above, not

more than 10 per cent of the land of this region has a surface slope of

less than 10 degrees (approximately 2 feet in 10), while 24 per cent

(see Pl. XII) of it has been cleared. In this region land with slopes

exceeding this can not be successfully cultivated for any considerable

time, because its surface is rapidly washed into the rivers below by

the heavy rains, and the same agency rapidly leaches out and carries to

the sea its more soluble and fertile ingredients. The valley lands have

already been largely cleared, and the farmers arc now following up the

mountain slopes. In many cases their cleared patches have well nigh

reached the mountain summits. This process is going on with greater

rapidity, because each short-lived hillside field must soon be abandoned.

The underbrush is destroyed, the trees are girdled, and for one,

two, or three years such a field is planted in corn, then a year in

grain, then one or two years in grass; then the grass gives place to

weeds, and the weeds to gullies. (See Pls. XX and XXI.)

|

|

PLATE XX. (A) NEWLY CLEARED MOUNTAIN FIELD PLANTED IN CORN,

RAPIDLY WASHING AWAY. (See pp. 26-28.) These steep fields will be

ruined and abandoned in less than a decade.

(B) RECENTLY CLEARED FIELD IMPOVERISHED AND ABANDONED.

(See pp. 26-28.) Such fields should be forever covered with

forest.

|

|

PLATE XXI. (A) BADLY WASHED MOUNTAIN FIELD IN THE SOUTHERN

APPALACHIAN REGION. (See pp. 26-28.)

(B) APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN FIELD COMPLETELY RUINED BY EROSION.

(See pp. 26-28.)

|

|

|

Agriculture on mountain slopes short lived in its benefits;

permanent in the resulting injuries.

|

Such a field has usually passed through its cycle in

five to ten years and another must be cleared to take its place. A

forest which is the growth of several centuries perishes in less than a

decade; a soil which is the accummulation of a thousand years has been

cleared, cultivated, abandoned, and is on the downward road to the sea

within less than a decade. Such is the brief life history of many

thousands of small mountain fields in this Southern Appalachian region.

But even the native farmer is beginning to realize that the clearing of

these mountain slopes is producing floods that wash away the valley

farms, and that the time must come when he will have successively

cleared and destroyed all his available mountain land. (See Pl.

XXXIV).

|

|

Some serious results from this forest clearing.

|

Fortunately the intelligence of the country is

awakening to other and larger results that are following this policy.

The soil thus removed may stop long enough on its way to the sea to silt

up the streams as they cross the low lands or may fill up the harbors as

the streams reach the coast. Every acre of mountain slope thus cleared

is a step in the more rapid destruction of the forests, of the soils, of

the rivers, and of the "eternal mountains" themselves—the

destruction of conditions which the combined wealth, intelligence, and

time of man can not restore in a region which now possesses infinite

possibilities for the benefit of the whole nation.

|

|

Grass does not hold the soil on the mountain slopes.

|

In the cool climate of New England the native grasses

form a dense sod which holds the hillside surfaces in place, so that

even where the forests have been removed there is little erosion. In the

Southern Appalachians, however, neither the grass, the legumes, nor the

other forage plants have been able to prevent this land erosion, and

their only safeguard for the future is the protection of the forests.

Hundreds of these steep mountain fields where selected grasses were sown

have been observed during the past few years, and the results, as

indicating a means of permanently holding these soils, have been

generally unsatisfactory. (See Pl. XXII.)

|

|

PLATE XXII. (A) WASHING OF GRASS-COVERED SOIL, TOP OF ROAN

MOUNTAIN. (See p. 27.) About the tops of these higher Southern

mountains the grasses grow more vigourously than at lower levels;

but even there the sod is not strong enough to prevent the washing

away of the soil.

(B) WASHING OF AN ABANDONED PASTURE FIELD. (See p. 27.)

This is a good illustration of the process by which these mountain

slopes are going to ruin.

|

|

|

Washing of mountain lands.

|

This washing away of the cleared mountain fields does

not always manifest itself in the formation of deep gullies. The

majority of these fields have slopes so steep that the water in its

downward course can not always move laterally to a sufficient degree

for its concentration and the washing out of such gullies. Each drop of

rain does its own work in battering and loosening the surface; and as it

carries downward the particles of soil it has captured it is joined by

only its closer neighbors. Hence frequently after a heavy rain the

surface of such a field looks as though it might have been harrowed or

even raked downward rather than plowed in larger furrows. From one of

these cleared fields more soil is sometimes removed by a single heavy

rain than during the preceding centuries while it was densely forest

covered.

|

|

Washing away of valley lands.

|

But while the rains are removing the soils of the

cleared mountain slopes the floods are removing the soils of the valley

farms. This is notably the case in the valleys, where the bordering

forests have been cleared to the largest extent. Year by year the

channels of the streams are widening and encroaching upon the adjacent

farms, and as the magnitude of the floods increases, these mountain

streams, transformed into swollen torrents, leave their course and plow

new channels across the fields. During the floods of the present year

thousands of acres of the most productive valley lands in this mountain

region have been damaged or destroyed by one or both of these processes.

(See Pls. XXIII and XXIV.)

|

|

PLATE XXIII. (A) UNWASHED VALLEY LANDS SURROUNDED BY FOREST-COVERED

MOUNTAINS. (See p. 27.) (See, also, Pl. IXb, p. 21.)

(B) BADLY WASHED MOUNTAIN VALLEY LANDS, BAKERSVILLE, N. C.

(See p. 27). The lower slopes of the mountains bordering this valley

are largely cleared.

|

|

PLATE XXIV. (A) VALLEY LANDS BADLY WASHED BY FLOODS. (See p. 27.)

These fertile valley lands in the Southern Appalachians will all be washed

away in a few decades unless the forests on the mountain slopes are protected.

(B) VALLEY LANDS RUINED BY RECENT FLOODS AND ABANDONED. (See p. 27.)

As long as the forests remain on the mountain the valleys can be cultivated.

|

|

|

Result of present policy.

|

It is, then, exactly true that the making of farms on

mountain slopes is destroying the farms in the valleys, and that unless

stopped by some external influence this process will proceed more

rapidly as the population of the region increases. It is therefore only

a question of time, to be measured not in centuries but in years, when,

unless this policy is changed, there will be no forests in this region

except on the small remnants—say 10 per cent of the

whole—where the mountain slopes are too precipitous and rocky to

make the cultivation of the lands possible, even by an Appalachian

mountaineer and his hoe.

|

|

Policy under proposed Government management.

|

If, on the other hand, the policy now advocated is

adopted, and all these steeper mountain slopes are incorporated into a

forest reserve, owned and controlled by the Government, the valley lands

will be protected from floods, and to the cultivation of these areas can

be added that of the gentler slopes, the whole to be terraced and kept

in a high state of cultivation by the native farmer, who will retain

ownership then as now. (See Pls. IX b and XXIII a.)

|

|

Guiding principle in Government management.

|

The guiding principle of the Government in the

creation of this forest reserve should be to protect the farmer in his

occupation and to insure the use of agricultural lands for agricultural

purposes; but also, and primarily, to maintain forever the forest cover

of these great and beautiful mountains, which can be perpetuated in no

other way. Under such a system the agriculture of this region will be

maintained on a permanently satisfactory basis. Under the present policy

it is advancing to certain ruin.

FOREST CLEARINGS, THE RIVERS, AND FLOODS.

|

|

This region is the source of many rivers.

|

Probably no region in the United States is better

watered or better drained than this; nor is there any other region which

can boast of being the source of so many streams. (See Pl. XII.) From

about its northern end the New River (Kanawha) flows northward and

westward and becomes a prominent tributary of the Ohio; along its

southeastern front the James, the Roanoke, the Yadkin, the Catawba, the

Broad, and the Savannah reach the Atlantic; near its southern end the

Chattahoochee and the Alabama flow directly into the Gulf of Mexico;

along its western the Hiwassee, the Tuckaseegee, the French Broad, the

Nolichucky, the Watauga, and the Holston drain westward through the

Tennessee into the Mississippi.

|

|

Value of these mountain rivers crossing the lowlands for water power.

|

Each of these greater rivers as it crosses the

Coastal Plain region toward the sea is navigable for light-draft

vessels. Each throughout its lower course is bordered by fertile

agricultural lands, which in the past contributed largely to the

nation's supply of corn, but during recent decades have begun to suffer

seriously from river floods. Each one of these streams along its course

through the mountains and across the hill country beyond by its water is

already a contributor to the manufacturing interests of the country (Pl.

XXV), and with improvement in the electrical transmission of power the

possibilities of manufacturing developments in this direction are

increasing rapidly every year. The measurements and estimates recently

made by the Government hydrographer show the aggregate available

undeveloped water power on the streams rising in this region to be more

than a million horsepower. On these streams water-power developments are

constantly in progress, but their value in the future will diminish as

the forests disappear.

|

|

|

PLATE XXV. WATER-POWER DEVELOPMENT AND COTTON MILLS AT COLUMBUS, GA.,

ON THE CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER. (See pp. 29, 139-142.) The sources of

this and numerous other important rivers are within the limits of

the proposed Appalachian forest reserve; and their value for water

power and navigation can be perpetuated only through the preservation

of these mountain forests.

|

|

|

Beauty of the mountain streams.

|

In the mountains themselves these streams have their

sources at elevations from 3,000 to 6,000 feet, and before reaching a

level of 2,000 feet many of them have reached considerable proportions.

They subsequently flow across the mountain region for distances of from

20 to 50 miles before breaking through the border ranges onto the

surrounding lowlands at elevations ranging from 1,000 to 1,200 feet. Along

their courses stretches of smooth water are never long, and the descent

is often accomplished by numerous rapids, cascades, and falls. (See Pl.

XXVII; also Pls. LXX and LXXI.) Such cascades, with descent in short

distances of from 10 to 50 feet, are abundant, while in some of the

smaller tributaries beautiful falls of from 100 to 300 feet are to be

found.

|

|

PLATE XXVI. (A) WATER POWER ON SALUDA RIVER, AT PELZER, S. C.

(See pp. 29, 141.)

(B) WATER POWER ON BROAD RIVER, AT COLUMBIA, S. C. (See pp. 29,

141.) These streams have their sources within the limits of the proposed

Appalachian forest reserve; and the perpetuation of these valuable water

powers depends on the preservation of these mountain forests.

|

|

|

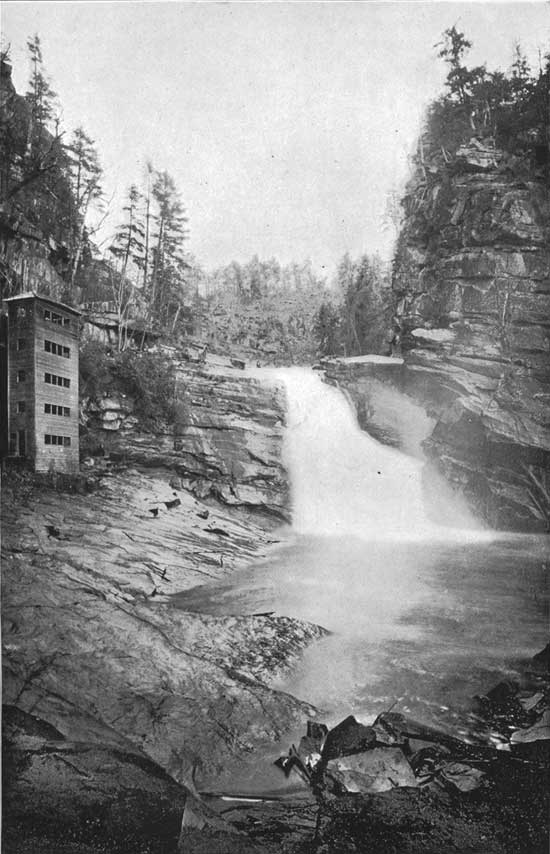

PLATE XXVII. CASCADES NEAR HEAD OF CATAWBA RIVER. (See pp. 29, 116.)

There are hundreds of cascades as beautiful as this in the Southern

Appalachians. As long as these mountain forests are preserved these

streams have a regular flow; united they furnish the water powers which

operate the factories valued at increasing millions.

|

|

|

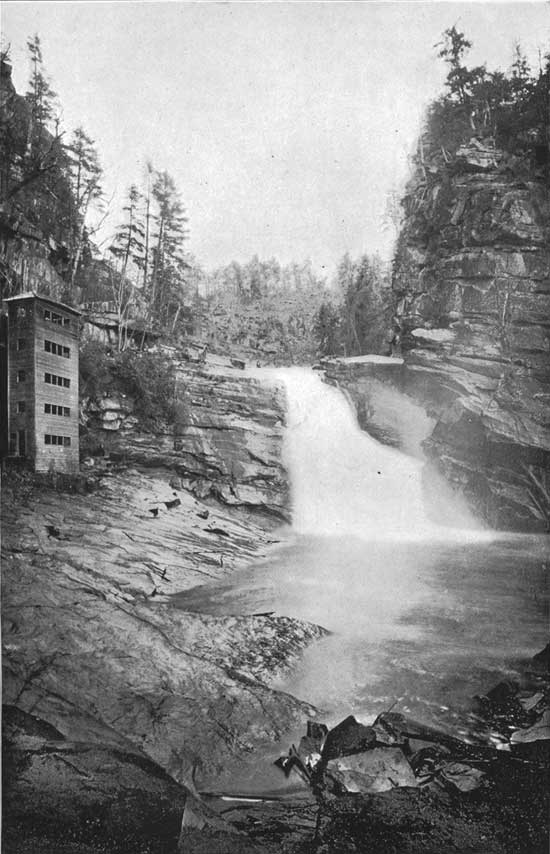

PLATE XXVIII. TALLULAH FALLS, GEORGIA. (See pp. 19, 28, 139.) There

is here a succession of beautiful cascades which have within a short

distance an aggregate descent of 335 feet.

|

|

|

I can not adequately describe the beauty and infinite

variety of these mountain brooks and larger streams. Always clear,

except immediately after the harder rains for the forests hold back the

soil—fed regularly from perpetual springs, they are among the

important assets of the South.

|

|

The river gorges of the region.

|

No gorges in eastern America can equal in depth and

wildness those carved across the Blue Ridge and the Unakas by these

streams in making their way through the marginal ranges of the Southern

Appalachians. About the headwaters of the Catawba, the Linville River,

after flowing for some miles parallel with the Blue Ridge, at an

elevation of 3,800 feet, rushes down its eastern slope with a fall of

1,000 feet in less than 3 miles, through a gorge 1,500 to 2,000 feet in

depth, a dozen miles in length, and with wall so steep and bottom so

narrow and rugged that few persons have succeeded in following its

course. (See Pl. LXXII.) Almost the same language might be used in

describing the gorge cut by the Pigeon River across the Unaka Mountains

southwest of Asheville; and there are a number of others cutting the

Blue Ridge and Unakas at different points that are worthy of comparison

with these. The same may be said of the gorges of the Tallulah and other

streams in northern Georgia.

But notwithstanding the steepness of the slopes of

these gorges, even where the descent is almost precipitous, they are

forest-covered except where the trees and shrubs have been destroyed by

fire and the soil has been removed by the storms. (See Pls. XXIX and

XLII.)

|

|

|

PLATE XXIX. FOREST-COVERED SLOPES OF LINVILLE GORGE SEEN FROM BYNUMS

BLUFF. If the forests on these steep slopes are once destroyed they

can not be restored, as the soils will be quickly removed by the

heavy rains.

|

|

|

Irregularity of streams in regions largely cleared.

|

The perpetuation of the streams and the maintenance

of their regular flow, so as to prevent floods and maintain their water

powers, are among the prime objects of forest preservation in the

Southern Appalachians. Nothing illustrates the need of this more fully

than the fact that on the neighboring streams, lying wholly within the

Piedmont plateau, where the forests have been cleared from areas

aggregating from 60 to 80 per cent of the whole, floods are frequent and

excessive. During the seasons of protracted drought source of the

smaller streams almost disappear, and the use of water power along

their course is either abandoned or largely supplemented by steam

power.

|

|

Forests regulate the flow of streams.

|

To-day the larger valuable water powers in the South

Atlantic region are mainly limited to the streams which have their

sources among the Southern Appalachian Mountains; and the waters of these

streams show a striking uniformity of flow as compared with the

streams lying wholly within the adjacent lowland country, where forest

clearing has been excessive. While the rainfall is somewhat greater in

the mountain region, it is a question of the regularity rather than the

volume of flow, and this depends upon the water storage. The soil in the

one region is as deep as in the other, and the slopes being gentler in

the low country, other things being equal, the water would soak into it

the more easily. In the mountain region itself the flow of the streams

along which proportionately large clearings have been made has become

decidedly more irregular, and the flood damages have greatly exceeded

those along other streams where the forests have not been disturbed. The

problem resolves itself into one of a forest cover for the soil.

This is just what one would expect who has been,

during a rainy season, in the heart of a mountain region where the lands

have not been cleared nor have forest fires destroyed the humus cover

from their surface. The rain drops are battered to pieces and their

force broken by the leaves and twigs of the trees, and when their spray

reaches the ferns, the grass, and the flowers below, instead of running

away down the surface slope it passes into the spongy humus, and thence

into the soil and the crevices among the rocks below. As much of this

supply as is not subsequently used by the growing plants emerges from

this storehouse weeks or months later in numberless springs. (See Pl.

XXXI.) The rain must be extremely abundant or long protracted to produce

any excessive increase in the flow of the adjacent brooks.

|

|

|

PLATE XXX. FORESTS REGULATING THE FLOW OF STREAMS IN THE SOUTHERN

APPALACHIAN MOUNTAINS. (See pp. 29-31; 137-142.) The leaves and

branches above break the force of the raindrops; the shrubs, ferns,

and humus below catch the water and pass it slowly downward into the

soil and rock crevices; and from this great natural reservoir,

weeks or even months later, this water emerges in the numberless

springs about the lower mountain slopes and feeds the great rivers

that cross the hill country below.

|

|

PLATE XXXI. (A) A SPRING ON SOUTHERN SLOPE OF MOUNT MITCHELL.

These perennial springs are fed by water stored in the forest-covered

slopes of these mountains. They maintain the regular flow of the many

mountain streams of this region.

(B) A MOUNTAIN BROOK IN THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS. In the

beautiful Sapphire country of North Carolina.

|

|

Heavy rainfall renders forest cover necessary.

|

The rainfall in this Southern Appalachian region, as

shown in Appendix D (p. 143), ranges from 60 inches for the year in

Georgia to 71 inches in North Carolina. Heavy rainfalls during short

periods are common. Even in an arid or semiarid region, where the

rainfall for the year may be 10 inches or less, the absence of the

forest cover results in a slow but sure removal of the soil from the

mountain slopes. Much more in a region of heavy rainfall, like that of

these southern mountains, when the forest cover has been destroyed will

the soil removal be certainly and rapidly accomplished.

|

|

Soil protection and water storage here are both forest problems.

|

In studying the streams of the more northern States

it is seen that the numerous lakes and the deposits of sand and gravel

spread over the hills and valleys of that region by the glaciers serve

to store the water and to preserve the uniformity in the flow of the

streams, and would accomplish much in this direction even were the

forests in that region entirely removed. In this southern region the

preservation of the soil and the streams is a task which the forests

alone must accomplish, and to that end they must be effectively

protected.

|

|

Proportion of cleared land in Appalachian region increasing.

|

The proportion of cleared and forest-covered land in

each of the great river drainage basins of the region is given on page

69, and as will be seen there, this proportion, though generally small,

varies considerably in the different basins. Taking the region as a

whole, at the present time about 24 per cent of the area has been

cleared. (See Pl. XII.) This proportion is an ever-increasing

one—increasing the more swiftly for the reason that new fields are

constantly being cleared and the abandoned fields are being eroded so

rapidly that they are seldom reforested. (See Pl. XXI.)

|

|

Landslides indicating heavy rains in past and necessity of forest cover.

Erosion of the forest-covered mountains exceedingly slow.

|

Here and there among the Southern Appalachians a

landslide extending over an acre, or several acres, has started, bearing

on its surface a section of the forest, but the larger trees below have

blocked its course within a few feet or a few yards of its original

position. (See Pl. XXXII.) The trees on its surface were tilted, but the

subsequent upward bending of their tops shows that the slip took place

ten, fifty or more than one hundred years ago. The abundance of such

evidence shows that these rain storms among the primeval forests have

been both frequent and heavy, but during the centuries these densely

forest-covered slopes have not lost their soils nor the soils their

fertility, nor has a furrow been washed. Trees of four centuries stand

to-day in the very bottom of shallow ravines and minor depressions (see

Pl. XXXIII), eroded before these forests covered the mountains. Had

these forests been removed a few of these great rains that started these

landslides would have cleaned the mountain slope of its recently formed

soil, and would have swept the valley below.

|

|

PLATE XXXII. (A) LANDSLIDE STOPPED BY THE FOREST, NORTH SLOPE OF

ROAN MOUNTAIN. (See p. 32.)

(B) SMALL LANDSLIDE AT A SPOT WHERE NO LARGE TREES WERE GROWING.

If it were not for this forest growth the soils on many steep mountain

slopes, when saturated from heavy rains, would either slide down like

avalanches, or be washed down by the rushing water.

|

|

|

PLATE XXXIII. LARGE POPLAR TREE GROWING IN MOUNTAIN RAVINE, ON THE

WEST SLOPE OF THE GREAT SMOKES. (See p. 32.)

|

|

|

The future will have its storms. Forests alone can protect mountains.

|

These mountains will continue to be the home of

storms. Their heavy rains will continue to drench the slopes, if cleared

of their forests, with increasing violence. Whether in the future these

rains shall be caught by fern and grass and humus, and received by a

deep, porous soil, to be given out as needed to the vegetation above and

the perpetual springs below, or whether it shall rush down bare, rocky

slopes to fill the gorges and carry destruction through the valleys

beyond, depends upon whether or not these forests are preserved.

|

|

Damages from recent floods in this region.

|

The terribly destructive work of the heavy rains in

washing away the farm lands on the mountain slopes and in the valleys

of this region, especially where the clearings have been greatest, has

already been described. It should be understood clearly, however, that

the dangers from these floods are not limited to the region about the

mountains. The floods from the May storm of the present year on the Blue

Ridge, about the sources of the Catawba, swept the best of the farm

lands along the course of that stream for upward of 200 miles, and cost

the farmers more than a million and a half of dollars. Am August storm

in the same region added a loss of half a million more by further

destruction on the Catawba lowlands. (See Pl. XXXIV.) Similarly, the

same May floods swept the valleys of the Yadkin in North Carolina, the

New (Kanawha) in Virginia and West Virginia, and the upper tributaries

of the Tennessee with resulting devastation, which, when added to that

on the Catawba, sums up to more than $7,000,000 damage. Add to this the

damages from floods on other streams rising in different parts of this

region during the spring and summer, and the total this year

approximates $10,000,000. (See Pls. XXXV and XXXVI.)

Such has been the story, on a smaller scale, of other

similar but less violent floods about the sources of these mountain-born

rivers during the past few years. If we are to continue the destruction

of these mountain forests, this story will have to be repeated in

successively larger editions in the future.

|

|

PLATE XXXIV. (A) SOIL REMOVED AND WHITE SAND SPREAD OVER THE SURFACE

OF THE CATAWBA RIVER LOWLANDS. (See pp. 32, 130.) The damages along this

river from the floods of May and August, 1901, aggregated about $1,500,000.

(B) LAYER OF SAND SPREAD OVER THE FERTILE LOWLANDS BORDERING THE

CATAWBA RIVER BY A FLOOD IN MAY, 1901. (See pp. 32, 130.)

|

|

PLATE XXXV. (A) FLOOD DAMAGES ON ELKHORN CREEK, IN WEST

VIRGINIA, JUNE, 1901. The damages from floods along streams rising

in this Southern Appalachian region, from April 30, to December 1,

1901, reached $10,000,000. Between December 1, 1901, and April 1,

1902, they reached $8,000,000 additional.

(B) DÉBRIS FROM FLOODS ON NOLICHUCKY RIVER, EAST

TENNESSEE, MAY 21, 1901. This d&deacute;bris consisting of the

wreck of farmhouses, furniture, lumber yards, bridges, cattle,

and probably several human bodies, covered 6 acres of fertile

farm land near Erwin, Tenn.

|

|

PLATE XXXVI. (A), left FLOOD DAMAGES TO RAILWAY ON DOE RIVER,

TENNESSEE. (See pp. 32, 130.)

(B), right FLOOD DAMAGES TO RAILWAY ON NOLICHUCKY RIVER,

EAST TENNESSEE. The flood damages here illustrated occurred in May,

1901. These and similar floods occurring during August and December,

1901, and January, February, and March, 1902, wrought damages to

railroad property in and about this Southern Appalachian mountain

region aggregating several million dollars.

|

|

sen_doc_84/report1.htm

Last Updated: 07-Apr-2008

|