|

WRANGELL-ST. ELIAS

A History of the Chisana Mining District, Alaska, 1890-1990 |

|

CHAPTER TWO

THE STAMPEDE

Upon reaching the Yukon River, Nelson and Taylor informed local residents about the Chisana strike. The Dawson City community reacted enthusiastically and by June 6 several parties were already preparing to leave for the diggings. Excitement waned, however, when no other prospectors arrived to confirm the pair's report. [1]

For their part, Nelson and Taylor required no further inducement. Finishing their business, they returned to Bonanza Creek heavily laden with food and equipment. They also brought several friends, including James and Nelson's former partner, Fred Best. [2]

The group's arrival was timely, as James and Wales had very nearly exhausted their supplies.

For days we were on Little Eldorado eating the handful of rough food, with no sugar, no flour, no salt. We had wild meat and, as we chewed on it, we had visions of other good things which gold would buy. [3]

James, Nelson, Wales, Taylor, Best, and their Dawson friends staked most of the property on Bonanza, Big Eldorado, and Little Eldorado Creeks. A rival, however, obtained one of the richer claims. At the time of James's strike, Carl Whitham was also prospecting around the mouth of Bonanza. One of the earliest on the scene, he acquired the second claim on Little Eldorado. [4]

Little Eldorado Creek was well suited for hand-mining methods, as its gravel was less than six feet thick and one hundred feet wide. Classic "poor man's diggings," such deposits required a minimal expense of equipment and labor to produce paying quantities of gold. [5]

As was the case in many placer areas, its gold was quite distinctive. Coarse and dark, it possessed a peculiar bronze-like cast, which miners attributed to a slight coating of iron oxide. Most particles were flat, indicating that they had originated in narrow seams, and ranged in value from one to ten cents. Nuggets worth from one to two dollars, however, were common, and larger ones were also occasionally found. One viewed by visiting Canadian geologist DeLorme D. Cairnes, for example, weighed a full eight ounces. [6]

Billy James and N. P. Nelson began sluicing Little Eldorado No. 1 on July 4, 1913. Assisted by Andy Taylor and former Dawson City bartender Tommy Doyle, the pair recovered nearly two hundred ounces in just two days. By August 2 they had already garnered $9,000, or an average of about $300 per day. [7]

While less productive than Little Eldorado No. 1, several other claims also yielded significant quantities of gold. Bonanza No. 6, for example, produced some four- and five-dollar pans, and even samples taken from Bonanza No. 3 averaged more than a dollar. [8]

|

| Fig. 5. A typical stampeder on the trail to Chisana, 1913. Note crosscut saw for whipsawing lumber. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Needing additional gear, Best returned to Dawson City about the middle of July. While there, he provided the local newspaper with a current description of the strike. Best related that both Bonanza and Little Eldorado were claimed "from end to end," and noted that when he left, stakers were also "planting poles on Coarse Money Gulch, Gold Run, Wilson, and other creeks in the immediate vicinity." [9]

Best's account electrified the Yukon, Alaska, and eventually much of the Pacific Northwest. [10] The Cordova Daily Alaskan, for example, proclaimed the strike as "the richest" since the Klondike, provoking defections which virtually emptied the Nizina gold camps and even briefly jeopardized the operation of Kennecott's copper complex. [11]

The Dawson Daily News confirmed the Cordova newspaper's story, adding that "at Blackburn and McCarthy none who could get away remained, . . . [T]his morning word came from Chitina that more than half the population of the town had left or would leave Monday for the Shushanna." [12]

Blackburn, McCarthy, and Chitina were not the only local communities affected. The find impacted Cordova as well. [13] The Daily Alaskan reported that public interest was intense and that scores of residents were preparing to go: "They are only awaiting further details as to the extent of the richness of the strike." [14] Many must have eventually left, for one witness claimed that after the departure of the northbound train, "you could fire a cannon down the main street . . . and not hit a soul." [15]

|

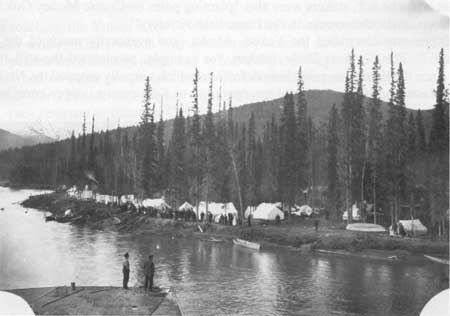

| Fig. 6. Staging area along the lower White River. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

When news of the discovery reached the outside world, it soon elicited a similar response. As in the case of the Klondike find, Seattle was particularly affected.

Gossip of the Shushanna strike was to be heard on all sides yesterday in the hotels and resorts [where] Alaskans are wont to congregate. Plans for hasty embarkation were being made and staid gold hunters of former days, who had not felt the call of the north in years, did not attempt to conceal their interest and enthusiasm. The 'fever' was very much in evidence. [16]

The liner Northwestern was one of the first to leave for the north. Friends of the departing gold seekers thronged the dock and automobiles lined the pier for more than a block in each direction. The Seattle Times noted the excitement, reporting that the waterfront had not experienced such activity since the Klondike days. [17]

|

| Fig. 7. Stampeders poling their boat up Beaver Creek, August 1913. Cairnes Collection, courtesy Earth Sciences Sector, Natural Resources Canada. |

Vancouver's boosters soon began a campaign to wrest some of the traffic away from Seattle. Their "Progress Club" initiated a "Chisana Day," and offered free maps to all interested stampeders. It also began a subscription drive to pay for advertising Canadian routes and promoting the benefits of local outfitting. By early August, their efforts seemed to have been at least partially successful. Ticket agents reported "a tremendous inquiry" and speculated that "several hundred northerners will leave this city and Victoria before the end of the month." [18]

Like their counterparts in Vancouver, Whitehorse residents also promoted the Chisana district. They, however, championed their own route into the region.

From the head of the Tanana [River] it will be something like one hundred and twenty-five miles overland to the discovery. On the White River light draught steamers can proceed about fourteen miles above the mouth of the Klutasin and to the mouth of [Beaver Creek]. On the latter it is said poling boats can be taken within ten miles of the scene of the strike. [19]

|

| Fig. 8. Horses fording a shallow channel of the Nizina River. Note that one horse is carrying an extra passenger. Stanley-Mason Collection, Tacoma Public Library. |

Fairbanks boosters, of course, disputed the superiority of this Yukon passage. "The [White] River at best is only navigable to the head of the Donjek,"they cautioned, "and that point is 105 miles from the scene of the strike." While they admitted that Dawson City was closer to the strike than Fairbanks, they warned that goods shipped through Canada were subject to customs duty at the border. The Tanana River, in contrast, was an "all-American" route. [20]

Most interior residents viewed the Tanana as the logical route to the diggings. Healy Lake trader William H. Newton, for example, claimed that from Tanana Crossing to the Chisana the water was "so slack that the wind will blow a boat upstream." Newton warned, however, that swift water between Fairbanks and Tanana Crossing could inhibit travel: "The best way then would be to mush to Tanana Crossing, build a boat there, and pole to the near field." [21]

W. H. Merritt also believed it would be relatively easy to ascend the Tanana. [22] Hoping to capture some of the stampeders' business, Merritt tried to establish a trading post on the Chisana River. Although he chartered the 101-ton Dusty Diamond to transport his freight, he failed to get anywhere near the Chisana district. [23]

Large boats, however, continued trying to reach the goldfield. Most, including the Tana, the Shushana, the White Seal, the Martha Clow, the Florence S., and the Samson, failed to reach even the Nabesna River. [24] The Northern Navigation Company's steamer Reliance got a little further, attaining the mouth of the Chisana and establishing the townsite of Reliance City. [25] Only a few smaller craft went up the Chisana River. The Marathon and the Mabel probably ascended the furthest, reaching a spot about six miles below the mouth of Scotty Creek where they founded Gasoline City. [26]

Prospectors approached the Chisana from every possible direction. Most were poorly equipped and many lacked a clear concept of where they were headed. Consequently, many failed to arrive, and of those who did, few remained for more than a few days. [27]

The experiences related by Gus Lepart and Tony Grisko were fairly typical of those approaching from the north. According to Lepart, he and Grisko

left Dawson with three others on July 27, and took a boat to the mouth of the White, whence we poled to the Donjek. Three of the boys left us there, and we bought their outfit, and continued with five dogs. Grisko and I then poled up to near the canyon, and struck across country with each dog carrying thirty pounds and each man fifty pounds, with rifles and blankets on top. We cached goods on the river bank for our return, and, with the dogs, carried in enough on the one trip to keep us going for seven weeks that we were in the diggings, with the exception of about seventy-five dollars worth of grub which we bought at Chisana City. We got to Wilson Creek August 25. [28]

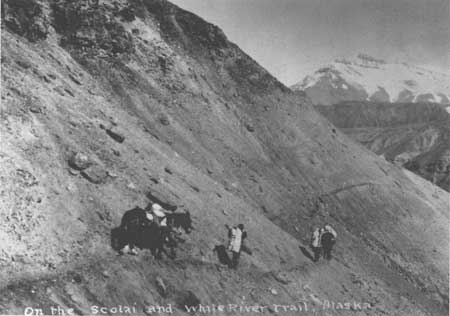

For those coming from the south, the route up the Chitistone River was fast, but particularly risky. George Hazelet, who traversed it in mid-July 1913, described this so-called "goat trail" as

an extremely dangerous place for horses, . . . being simply a sheep trail widened to about two feet. The drop to the bottom is as much as two thousand feet in places and should horse or man lose his footing he could not stop till he reached the bottom. [29]

Ruben Lindblom, who passed that way with his brother Hugo about the same time as Hazelet, recorded another commonly encountered peril:

Broke camp this morning intending to ford the river on foot as no parties with horses have shown up yet. We made our packs snug, tied our rifles to the packs so as to have our hands free, then cut a long pole and started abreast into the water . . . . The stream at this point was not very wide, about sixty yards or so. We had gotten half way over, with the water well above our waists when I went down, but the others kept their feet so I managed to get up again by holding onto the pole. The water was running swift, a great deal more so than it seemed to be when standing on the bank, and the gravel on the bottom was moving which made it well nigh impossible to keep ones feet from being washed from under him. We got straightened out once more . . . [but] had not taken but a few steps forward when we all seemed to go under at about the same time. I know I was under water some little distance before I saw daylight again but whenever I got partly straightened up the water would hit my pack and roll me over and over. But I kept kicking whenever my feet touched bottom and soon I stopped and found that I had ahold of Hugo and he was hanging onto me, both spitting out water and blowing like a porpoise. I glanced hurriedly down steam and saw Jacques with his arms around a block of ice which had stranded close to shore in shallow water. Mardi was just crawling out of the water on the opposite side of the river from the rest of us, and was so excited that he grabbed the hat off his head and threw it back into the water. Jacques and I lost our hats but Hugo saved his. We also lost a shovel. But we congratulated ourselves on getting thru with such a slight loss. [30]

|

| Fig. 9. Negotiating the treacherous "goat trail" through Chitistone Canyon. Zacharias Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

A government survey party, then employed in locating the international boundary between the United States and Canada, had the opportunity to observe many Chisana stampeders as they crossed Skolai Pass.

About 75 percent . . . were very inadequately equipped for a trip of this description, and as they seemed to consider a government survey party a sort of general supply depot, it became the duty of the survey to provide meals for them, to sell them what provisions could be spared, and even to provide clothing and shoes, in addition to furnishing minute directions as to how to get to the diggings. [31]

On his return to Seattle, survey chief Thomas Riggs, Jr. noted that his party had met one man

going into the interior with a horse on which he had packed ten pounds of raisins, having been informed that raisins were unusually efficacious in sustaining life in that country. We found scores of persons who had absolutely no idea how to pack their horses and who were carrying in supplies that could not possibly sustain them. [32]

Canadian geologist Delorme D. Cairnes, who visited the Chisana district in late July, provided a similar account. He related meeting many stampeders "who had been three weeks on the way, wandering all over the country and living principally on gophers." [33]

We met stampeders all through the woods while on our way back to Dawson. The men seemed to be unable to follow the trail up [Beaver Creek]. Forty miles this side of [the Chisana district], we met a man in a gulch who shouted over to us and asked if he had reached the 'diggins.' It seems a good many have absolutely no knowledge of traveling though a wild open country. [34]

Considering the above descriptions, it is not surprising that approximately a dozen stampeders perished trying to reach the goldfield. Most drowned crossing glacial torrents, but some undoubtedly died from exposure and a few may actually have starved to death. [35]

Even after reaching the diggings, provisions remained practically unprocurable. According to Ruben Lindblom, one party purchased

three pounds of flour for twenty dollars and had a hard time to get it at all, as the man who sold it would rather have kept the flour than part with it at any price, but merely did so to help the other fellow out who was entirely out of provisions. [36]

Neil Finnesand faced a similar situation. While the district's cheapest food cost $1.00 a pound, rice and sugar fetched $1.25 a cup.

|

| Fig. 10. Mr. and Mrs. Fletcher Hamshaw in camp. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

If a sack of flour was brought in, no one was allowed to buy a whole sack. They could just get two or three pounds. However, lots of meat was available--sheep and caribou--and the prospectors lived on that. [37]

Despite such hardships, several thousand stampeders reached the Chisana district between July and October 1913. Fletcher T. Hamshaw, for example, was one of the earliest arrivals. The well known mineral developer and his sixteen-man crew were prospecting for copper on the upper White River when they first heard news of the strike. An aggressive entrepreneur, Hamshaw used whatever means were necessary to acquire such potentially valuable ground, including employing members of his "former" crew to locate claims. [38]

Local prospectors objected to the practice, arguing that Hamshaw was attempting to monopolize the area by evading the spirit, if not the letter, of the law. Hamshaw, however, denied any wrongdoing:

When we left North Fork Island to go to the strike, all of my men were discharged and paid off, and all went to the diggings and staked for themselves, except my engineers, packers, and cooks. Anyone of these whose claims were purchased by me was paid for his claims the same as though I had bought them from any other person. [39]

|

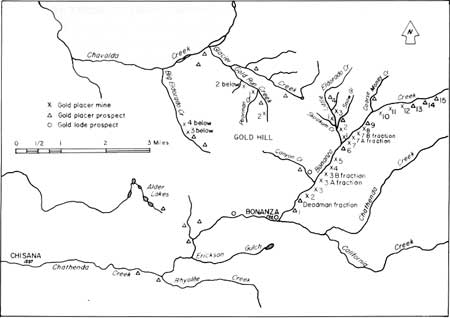

| Fig. 11. Mining claims in the Gold Hill area, 1914. |

Hamshaw initially staked the mouth of Bonanza Creek, but abandoned the site when he failed to locate any productive ground. Moving his outfit down Chathenda Creek, he next tried a bench claim where he was equally unsuccessful. Hamshaw also prospected Chavolda Creek, ground-sluicing near the mouth of Big Eldorado Creek. [40]

Most of Big Eldorado, however, was already taken. Billy James had located a discovery claim on the upper creek, while W. D. "Dud" McKinney and Anthony McGettigan had selected much of the rest. None of the three, however, actually mined Big Eldorado that first season. Leasing their claims to others, the trio worked more promising property on Bonanza Creek. [41]

By the middle of July, prospectors had selected virtually all available sites. Those arriving later either turned around at once, staked "wildcats," jumped someone else's claim, or continued into adjoining districts. Even those who obtained a favorable tract usually left immediately, returning later with a sufficiently large outfit to complete their assessments. [42]

George Hazelet and his two sons were typical late arrivals. Reaching Bonanza Creek on July 30, they found about 175 prospectors and signs of frenzied activity. Stakes were everywhere, not just along the creek but also far up the hillsides. [43] Hazelet puzzled over how to proceed. Before he had made a decision, however, one of his sons heard about some outlying property that was still available. Setting out late in the evening, the family visited the spot and eventually staked two wildcat claims on Chicken Creek, a tributary of Glacier Creek lying just over the divide from Little Eldorado. [44]

|

| Fig. 12. A well-dressed Chisana prospector, c. 1914 Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

They began their required assessment work after only a few days' rest. On August 10 they completed a forty-five-foot-long ditch on Chicken No. 4, which Hazelet had located by power-of-attorney for Cordova Judge John Y. Ostrander. Two days later they finished a similar trench on Chicken No. 3. Neither claim, however, ever yielded any gold. [45]

Ruben Lindblom also located a claim. Reaching Chathenda Creek on July 31, he and a frenchman named Jacques explored the surrounding countryside:

We had gone perhaps a mile from camp keeping a lookout for signs of new mining or works of any kind, when we found a sort of sign . . . [marked] 'Diggings on Johnson Creek.' We started up the mountain and soon struck a trail which showed fresh men tracks. Had gone a couple of miles when it commenced raining but we kept going, and after a while came to where some parties had located mining claims, dated the same day we came to Johnson Creek. Found a number of claims located on a small creek which we followed about two miles where we each located a claim, numbers 4 and 5 above discovery claim. It rained incessantly so we were wet as could be before we were ready to hit back to camp which was some four or five miles from where we located our claims. [46]

The following day, Lindblom and his associates remained in camp

too tired and footsore to go anywhere. A man came in about noon whom we had seen on the trail coming to the diggings. . . . This fellow reported having been on, and prospected the streams where rumor had it gold had been found in paying quantities, but he said the reported strike was a fake and he could not find any gold on but one claim, the first discovery on Little Eldorado, all of which did not tend to raise our spirits or encourage us any. [47]

Disheartened by such reports, on August 2 the group decided to return to McCarthy.

Have decided to hit the back trail to-morrow because our grub is very low and no chance to get any more in here. . . . We did not do any work on our locations, nor did we record them so they are open for some one else to jump but fear no one will find much on them. [48]

While Lindblom's ground could legitimately be re-staked, recorded claims were supposed to be immune from seizure. Jealous prospectors, however, soon coveted those properties as well.

Predictably, one major dispute focused on James's holdings. On September 23, Dawson residents Hugh Brady and Henry Dubois sued the miner, claiming that an outdated grubstake agreement entitled them to a share of his discovery. Although they obtained an injunction that temporarily halted mining on his claims, the matter was ultimately settled out of court, and most of the property was returned to James. [49]

|

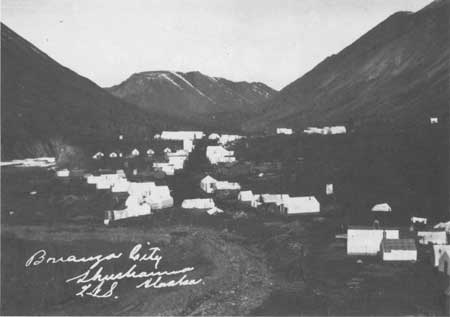

| Fig. 13. Bonanza City, c. 1914. Stanley Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

Frank Purdy, Fred Best's former partner in the Cassiar Roadhouse, occupied Dan Sutherland's fraction on Big Eldorado Creek and ignored all demands to leave. [50] Hoping to avoid violence, Sutherland, too, sought his recourse in the courts. A Cordova jury, however, inexplicably awarded the ground to Purdy. Sutherland appealed the decision and eventually prevailed, but it was January 1919 before he finally regained possession. [51]

Dud McKinney, seemingly less sophisticated than the others, employed a more traditional approach. When a claimjumper tried to take his property, he merely removed the offending party at gun-point. [52]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wrst/chisana/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 21-Mar-2008