|

WRANGELL-ST. ELIAS

A History of the Chisana Mining District, Alaska, 1890-1990 |

|

Chapter Three

THE BRIEF BOOM

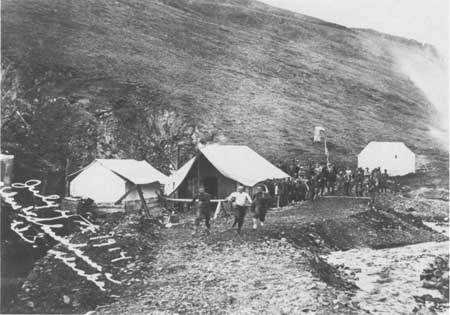

The Chisana district's first recording office opened on July 22, 1913, in a tent at the mouth of Bonanza Creek, with Horatio E. Morgan serving as U.S. commissioner and recorder. Business at the office was brisk. By mid-August, Morgan had already registered about 250 claims. [1]

Unfortunately, problems quickly developed. Not only were new arrivals accused of jumping claims but there were also widespread complaints about Morgan's bookkeeping methods. The recorder tried to defend his actions. While he admitted that his books--a hotel register and accounts ledger--were crude, he claimed that they were scrupulously honest. Faced with growing criticism, however, Morgan soon resigned. [2]

Meanwhile, George Hazelet was also busy. A consummate speculator, the Cordova businessman began seeking an appropriate location for a townsite. Hazelet selected two 160-acre parcels, "just below Johnson, east of Chisana and south of Wilson." [3] Named "Woodrow," this community became the site of the district's second recording office, managed by acting U.S. Commissioner J. J. Finnegan. [4]

|

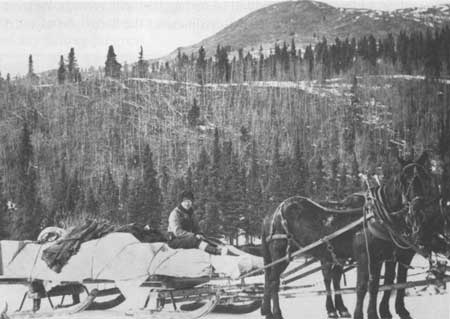

| Fig. 14, Freight headed up Chathenda Creek, c. 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Local prospectors soon objected to the location of Finnegan's office. By placing it in Woodrow, the commissioner forced them to walk nearly eight miles every time they wished to conduct business. Despite their complaints, however, Finnegan refused to move. [5]

On September 9. 1913, seventy-five miners met near the mouth of Chathenda Creek to address some of their common problems. Before the day ended, the group organized the Chathenda Mining District and established a new townsite, which they christened "Johnson City." They also removed Finnegan as acting commissioner and selected George E. "Ned" Hill as his temporary replacement. [6]

The district's first cold weather provoked an exodus of stampeders, with some bartering their entire outfits to finance their transportation home. Even James, Wales, and Nelson deserted the region. Having accumulated a hefty nest egg before shutting down for the season, the three headed south to enjoy a relaxing winter. [7]

Although mining activity dwindled, Johnson City continued to grow. By the middle of October, nearly all townsite lots had been staked and the village contained about two hundred cabins. [8] Among other amenities, it boasted two streets, two grocery stores, and the district's third recording office. [9] It also possessed a post office, run by former steamboat captain Theodore Kettleson. Despite the wishes of most local residents, however, postal officials insisted on redesignating the site "Chisana City." [10]

|

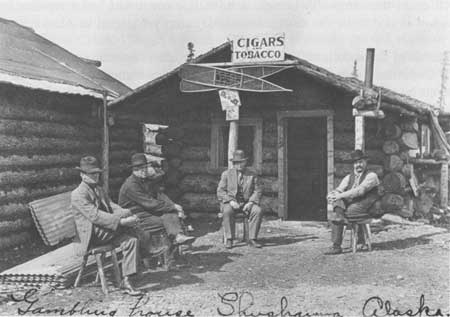

| Fig. 15. Grant Reed's store in Bonanza City, 1914. Zacharias Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

Word soon reached the town that federal authorities had chosen Anthony J. "Tony" Dimond of Valdez as its new commissioner. [11] A former gold miner on Young Creek in the Nizina district, Dimond was widely known and believed to be scrupulously honest. The Chitina Leader applauded the selection, suggesting that it marked an end to the capricious practices of the past: "There will be no juggling with records, no over charges and no connivance with big interests to the detriment of the hardy son of toil." [12]

Despite such support, Dimond hesitated to accept the position. The post was a gamble because the commissioner had to depend on fees for his salary. If mining activity declined, the recording business would slow, and fee opportunities would diminish. "If the camp is good," Dimond told a friend, "I will make a lot of money, if it's a failure, I'll lose a thousand dollars, which it will cost me to get in there." In the end, however, Dimond agreed to serve. [13]

During the fall of 1913, George Hazelet decided to increase Cordova's share of the market by creating a safer and more direct route to the diggings. That September he blazed a path across the Nizina, Rohn, and Chisana Glaciers. Designed to be utilized either winter or summer, his trail was short and possessed practically no grades over 12 percent. [14] Skagway boosters, who logically championed Canadian routes to the goldfield, questioned the viability of this glacier trail. They maintained that Hazelet was suffering from delusions, "produced no doubt by a sight of gold in the Chisana." [15]

|

| Fig. 16. A roadhouse on the Hazelet trail, 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Others appeared far more optimistic. Seattle resident and former Klondike stampeder T. G. Jones, for example, believed that Hazelet's route would be suitable for his specially made automobile, which he bragged could carry "about a ton of supplies" while retaining "ample power to run up hill." Although he transported his machine to McCarthy, a brush fire then raging along the trail a few miles to the south probably precluded any further progress. [16]

Tony Dimond was one of the first to utilize Hazelet's trail, reaching Chisana City in late November. To his dismay, he found the district's records badly organized and food scarce. Writing to his friend and former partner Joseph H. Murray, he dismissed the area's prospects, speculating that if local miners found as much pay as the two of them had discovered on Young Creek, "they would go wild." [17]

December brought profound changes to Chisana City. Dimond assumed his office at the beginning of the month, becoming the area's fourth commissioner. As one of his first official duties, he officiated at the marriage of O. J. Wheatly to Berta Cochrane, the head of the local Red Cross hospital. Later, Frank Miller opened the town's first saloon, appropriately calling his establishment the "Miner's Home." [18] The growing community now included about four hundred cabins and boasted four stores, two meat markets, two barber shops, two restaurants, a hotel, and a boarding house. [19]

|

| Fig. 17. The Miner's Home Bar in Chisana City, c. 1914. Zacharias Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

Near the close of the year, the district's miners received some other exciting news. A financial consortium of pioneer Alaskans, including John J. "Jack" Price, Frank Manley, and E. J. Ives offered the widely reported sum of $500,000 to lease the property belonging to James, Wales, Nelson, and their silent partner, William A. "Billy" Johnson. The four accepted the syndicate's bid and transferred thirteen claims, including the richest one of all on Little Eldorado. [20]

The first year's production in the Chisana district was surprisingly low. Prospectors only recovered about 1,935 ounces of gold, worth approximately $40,000. Despite the low return, most prospectors still believed in the area's potential and predicted that the following summer would bring important new discoveries. [21]

Many operators, in fact, continued to work throughout the winter, thawing the frozen ground as they slowly progressed toward bedrock. Fred Best and various lessees mined on Bonanza Nos. 3, 3A, 7, 7A, 8, 8A, and 18. [22] James E. Hagen and his partners prospected Big Eldorado Creek, reportedly recovering some gravel that yielded thirty cents to the pan. [23] Charles Bush and three colleagues even worked Gold Run, sinking drift holes at the mouth of Discovery Pup. [24]

|

| Fig. 18. The Gambling House in Chisana City, c. 1914. Zacharias Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

Still expanding, Chisana City began to assume an air of permanence. Structures were more elaborate and some, like Sam Shucklin's clothing store, even sported glass windows. Many buildings were also larger. W. H. Simpson and Louie Belney, for example, constructed a two-story cabin, which they rented to the government. The biggest building in town, it was shared by Dimond, his assistant Tony McGettigan, and the newly appointed deputy marshal, Frank H. Hoffman. [25] Chisana City was now a major Alaskan community, described by one newspaper as the "largest log cabin town in the world." [26]

Seattle reporter Grace G. Bostwick spent that first winter at Chisana City. In March she related that

the camp is fast assuming the airs and ways of a town. Men mostly shave now, where formerly they were rough and bearded. They are also more particular about their clothing. The most interesting period of the camp . . . the pioneer days . . . when one after another of the first cabins were built, when delicacies of any sort were absolutely unknown, and when magazines and books were prizes eagerly longed for are past. . . . There are by this time two bath tubs in the place, as there are brooms, tea kettles, and many other luxuries formerly unknown. It only remains for the eagerly anticipated strike to materialize, in which event the camp will become a bona fide town with great rapidity, even though it is said to be the most inaccessible camp yet started in Alaska. [27]

|

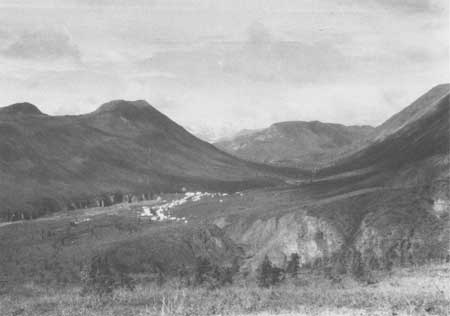

| Fig. 19. Bonanza City from the northeast. Capps Collection, courtesy of United States Geological Survey. |

The camp at the mouth of Bonanza Creek was also beginning to look more like a "town." Commonly called Bonanza City, it had grown throughout the winter, and by spring even included several women. Although still made up mostly of tents, it now possessed a few cabins, as well as four stores, two hotels, and a restaurant. [28]

The increasing activity, while welcomed by the miners, soon devastated the Native community of Cross Creek Village. Their subsistence opportunities, for example, substantially declined. Hungry prospectors rapidly depleted small game populations. Cairnes, for example, claimed that many Chisana stampeders lived entirely on ptarmigan "for days or even weeks at a time." [29] Grant Reed confirmed Cairnes report, noting that one man with a willow stick could easily harvest a flour sack full of the birds. [30]

|

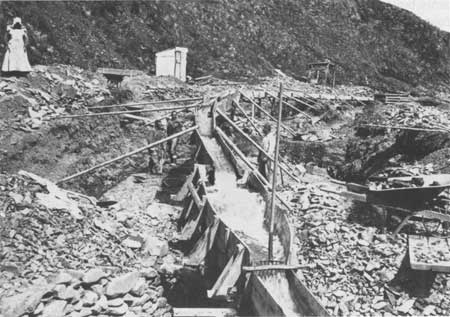

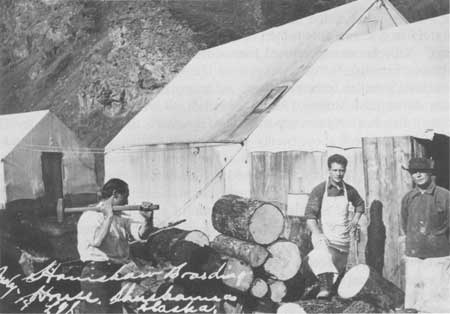

| Fig. 20. Hamshaw's Camp on Bonanza No. 6, 1914. Capps Collection, courtesy United States Geological Survey. |

Big game populations also dwindled. As early as August 1913, George Hazelet warned that while game remained plentiful, it was "being rapidly driven back. . . . The game law should be rigidly enforced in that country at once." [31] Territorial officials however, seem to have ignored Hazelet's warning. By spring 1914, local prospectors and market hunters had killed about 2,000 dall sheep, virtually eliminating them from the vicinity. [32]

Some of Cross Creek Village's twenty-five or so residents moved north or west to escape the unwelcome impact of the gold discovery. Others, attracted by the stores and promise of cash labor, abandoned their traditional locale and moved to Chisana City. [33]

At the beginning of 1914, Manley, Price, and Ives assigned their newly acquired property to Fletcher Hamshaw. Anticipating a busy summer, the operator moved eight steam boilers and a portable sawmill into the district. Crews soon set up the sawmill and began cutting the lumber necessary for large-scale sluicing operations. [34]

Hamshaw situated his main camp on the south side of Bonanza Creek at the mouth of Little Eldorado. Nearly a community of its own, it consisted of about sixteen tents, including offices, a mess hall, a commissary, and sleeping quarters. While somewhat isolated, both a trail and a telephone line linked the camp with Hamshaw's warehouse in Bonanza City. [35]

|

| Fig. 21. Mining on Bonanza No. 5, 1914. Note boomer dam in middle background. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Other Chisana operations were far less elaborate. Only one man, for example, worked the fraction lying above Bonanza No. 1. [36]

Bonanza No. 2 was a more typical example. Here, seven men mined for most of the season. In order to work the canyon floor, they diverted the creek first to one side and then the other, bringing water to their sluice boxes through a canvas hose. Although the operators recovered approximately $12,000 worth of gold, nuggets were rare. Even the largest was only valued at around four dollars. [37]

Ten men worked Bonanza No. 3. Beginning operations about six hundred feet below the claim's upper limit, they built a three-hundred-foot-long flume to carry the creek past their "open-cut." To recover the gold, they employed a dump box and about a hundred feet of sluice box equipped with pole riffles. The mining, however, was still done entirely by hand, utilizing a technique known as "shoveling-in." [38]

Fred Best and five employees worked Bonanza No. 3A Fraction. The group utilized a 120-foot flume to carry the stream past their cut, and employed a dozen, 12-foot sluice boxes to wash their paydirt. This claim produced much coarser gold than Bonanza No. 2. More than half was composed of nuggets valued in excess of $5.00, including one worth $61.80. [39]

|

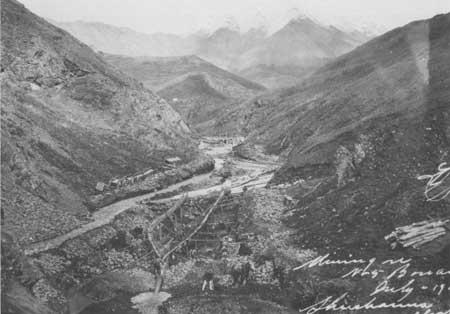

| Fig. 22. Mining on Bonanza No. 7, July 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Mining also resumed on Bonanza No. 3B Fraction, where Joe P. McClellan had recovered several thousand dollars worth of gold the previous summer. [40] Ten men constructed a 350-foot flume to divert the creek past their diggings and employed a set of sixteen sluice boxes to clean their gravel. [41]

Hamshaw concentrated his efforts on Bonanza Nos. 4 and 5 and No. 1 on Little Eldorado, engaging a crew which sometimes approached one hundred men. Like most miners in the district, he generally ground-sluiced to remove the overburden, leaving the lower foot or two of gravel to be shoveled into the sluice boxes by hand. Hamshaw, however, employed a horse team and scraper to remove the tailings from the lower end of his line. [42]

The operator's efforts were quite successful. At Bonanza No. 4, for example, his crews excavated 974 linear feet of creek bottom, recovering about $21,100 on a $14,800 investment, or a net profit of around 42 percent. He also mined Bonanza No. 5, moving 5,620 cubic yards of gravel from 833 linear feet of the stream. This site, however, was less productive, returning only around $20,500 on his $15,500 investment. [43]

Fred Best operated Bonanza No. 7. [44] His men did not build a flume, but instead employed the method used on Bonanza No. 2: they alternately moved the creek from one side of its canyon to the other. Here, however, the miners constructed an automatic "boomer" dam to eliminate most the surface gravel before they began to shovel. [45] Best utilized similar techniques on No. 7A, an approximately five-hundred-foot-long fraction lying above Bonanza No. 7. [46]

|

| Fig. 23. Mining on Bonanza No. 11, c. 1914. Note use of horse scraper. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Hamshaw worked Bonanza No. 8 for part of the summer, briefly employing sixteen men. By late July, however, they had encountered so little gold that the miner suspended further operations. Later in the season Jim Hagen mined the claim, but he only made about six hundred dollars. [47]

Lem Gates and Dud McKinney did far better on Bonanza No. 8 Fraction. Leasing the claim from Fred Best, they reportedly recovered six thousand dollars in gold. Further up Bonanza, the returns were more modest. On No. 9, for example, Henry Dubois made little more than wages. [48]

Two parties examined Bonanza No. 10. While a lessee explored the lower half, Carl Whitham worked the upper. Like Hamshaw's, his crew utilized a horse-drawn scraper to remove the surface gravel. [49]

Miners named McKay and Clinton prospected the lower end of claim No. 11, but found no productive ground. Dud McKinney and Lem Gates achieved better results on the other half. Late in the season they located a patch of bedrock which yielded six dollars to the square foot and reportedly recovered close to five thousand dollars. [50] Gates, however, never got to enjoy his newfound wealth. Following a prolonged illness, he died that August and was buried in Chisana City. [51]

|

| Fig. 24. Billy James (second from left) shoveling-in on Little Eldorado No. 1, August 1913. Cairnes Collection, courtesy Earth Sciences Sector, Natural Resources Canada. |

Three men leased the lower portion of claim No. 12 in 1914, using wheelbarrows to remove the overburden. Another three worked the property's upper half, where they located sufficient water to clean about 1,500 square feet of bedrock. Neither, however, found much gold. [52]

Of all the claims in the district, Little Eldorado No. 1 remained the most productive. Moving 9,220 cubic yards of gravel from 1,029 linear feet of the creek bottom, Fletcher Hamshaw recovered $51,952 worth of gold. [53]

Carl Whitham spent the entire summer working Little Eldorado No. 2. Starting with about fifteen lengths of sluice box, his seven employees gradually added more as their mining progressed upstream. They also employed pressurized water to keep tailings from blocking the lower end of their line. [54]

Little Eldorado No. 3 was far less productive. Although Waggoner and Johnson operated the claim throughout the season, they only cleared about five thousand dollars. [55]

|

| Fig. 25. The Hamshaws at home on Little Eldorado Creek, June 1915. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Charles Range, George Stone, and four associates leased Skookum Creek No. 1 from owner Bud Sargent. Beginning at its mouth, which lies on Little Eldorado No. 2, they worked their way upstream until, by the end of July, they had excavated 224 linear feet of the creek bottom. The miners experienced difficulties, however, acquiring sufficient water with which to wash their gravel. Although they increased their supply by constructing a ditch to the head of Little Eldorado, they failed to muster a sufficient head. Consequently, they had to accumulate water and to sluice only intermittently. Nevertheless, their efforts were successful. They recovered substantial gold, including many $10 and $20 nuggets and one worth $52. [56]

Several prospectors, including Whitehorse resident J. E. McGuire, examined Snow Gulch, another tributary of Little Eldorado. Although they found workable gravel in both the stream bed and on the benches, they had to delay their work. Until mining stopped on Little Eldorado No. 2, there was nowhere to dispose of the tailings. [57]

Miners working Big Eldorado Creek were at least moderately successful. The stream produced five thousand dollars in gold during the 1914 season, with one operator named Mike O'Malley recovering nearly half of that amount. Upper Discovery, part of the block held by Hamshaw, was leased to two men who seem to have only prospected the property. Two others worked No. 1 Below, but it yielded little more than wages. More vigorous activity occurred on claim No. 3 Below. Here, ten men mined about 250 linear feet of creek bottom. [58]

|

| Fig. 26. Mining on Glacier Creek, c. 1914. Note use of sluice fork to catch larger stones. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

No. 4 Below was also worked intensively. Two men ground-sluiced off about four feet of surface gravel before beginning to shovel-in. By the end of the summer, they had excavated six hundred linear feet. Their profits, however, were disappointing, with the operators reporting "only a fair return." [59]

Gold Run experienced a similar level of activity. Six men operated No. 2 Below, located just above its junction with Glacier Creek. Although they eventually worked about 150 linear feet of creek bottom, this claim barely paid its expenses. [60]

Four men mined Gold Run No. 1 Above, where winter drift shafts had encountered an encouraging amount of gold. Unfortunately, Gold Run's water supply proved to be too meager for efficient mining. To alleviate this deficiency, its operators constructed a one-half-mile-long ditch to tap the upper part of Discovery Pup, and a dam with which to consolidate the resulting water. Their strategy succeeded and they eventually excavated about five hundred linear feet. [61]

|

| Fig. 27. A typical miner's residence above Bonanza Creek. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

No. 2 Above, located near the head of the Gold Run basin, got far less attention. Here, one man prospected the benches throughout the summer. [62]

Poorman Creek, Gold Run's largest tributary, also received some limited action on claim No. 1. As the stream was much too small to furnish an adequate head of water, its operators built two dams to impound a sufficient supply. They also assembled nine, twelve-foot-long sluice box segments. Their efforts were in vain, however, as they recovered insufficient gold to justify further mining. [63]

Other creeks were also examined. Dawson resident William Steinberger, for example, reported finding good prospects on Canyon Creek during 1914. Prospectors claimed to have discovered pay on the benches of Coarse Money Creek as well. Those working Chathenda and Chavolda Creeks had far poorer luck. None recovered any appreciable quantity of gold. [64]

While most miners concentrated on mining surface placers, a few sunk shafts. Some were even rather extensive. One dug near the mouth of Dry Gulch by Anthony McGuire, for example, was ninety-six-feet deep. All, however, were wasted efforts. [65]

By mid-summer opinions regarding the promise of the Chisana district varied widely. Most acknowledged some of the region's drawbacks. The gold bearing area, for example, was relatively small:

|

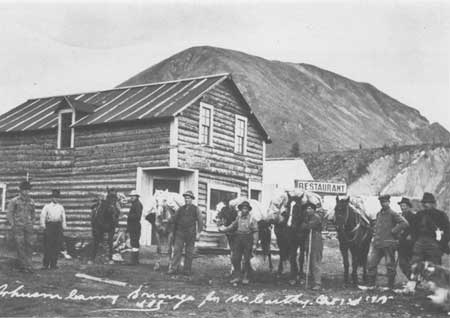

| Fig. 28. Sidney "Too Much" Johnson's pack train leaving Bonanza City for McCarthy, 1915. Stanley Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

Exclusive of a few claims from which some gold was taken during prospecting operations, all the gravels which have been profitably mined can be included within a circle only five miles in diameter, with Gold Hill as its center. . . . In the whole district mining was actively carried on during the summer of 1914 on about twenty-one claims . . . . [66]

It was also an expensive place to mine. Labor was prohibitively high, generally costing around six dollars per day, plus board. Stephen R. Capps believed that conditions in the district justified the expense. He cautioned, however, that it would eventually curtail development, as "much ground can not now be worked that would yield a profit if the labor cost were less." [67]

Apparently agreeing with Capps, Hamshaw offered his workers only five dollars per day, to be paid by draft on a Seattle bank. On June 16, the 115-man Shushanna Miners Association rejected his proposal, insisting that they be paid in gold at the six-dollar rate. Faced with a strike, Hamshaw eventually acceded to the group's demands. [68]

Fred Best also experienced some labor problems on Bonanza No. 7. His, however, were far less serious than Hamshaw's. After complaining about their wages for nearly a week, Best's men cooled down and returned to work at their original rate of pay. [69]

|

| Fig. 29. Sledding logs up Chathenda Creek, c. 1915. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

The district weathered some other difficulties as well. As no timber occurred near the mines, wood was in short supply. While the area now possessed two sawmills, lumber still cost between $125 and $150 per thousand board feet at the mill, and transportation charges were high. Even firewood brought forty dollars a cord when delivered to the mouth of Little Eldorado. [70]

Food also remained expensive. Fred Best noted that

. . . with the storekeepers arriving daily and hoping to 'get rich quick,' prices which are already too high, are increasing. Flour--forty cents per pound; sugar--fifty cents per pound; beans--twenty-five cents; other things in proportion--no 'luxury items' included here! [71]

Despite such obvious drawbacks, some individuals continued to promote the district. Harold H. Wailer, a young mining engineer from Seattle, for example, assured newsmen that Chisana was far from being "a fizzle." Predicting that the season's production would reach $400,000, he described it as ". . . a sporting proposition." [72]

|

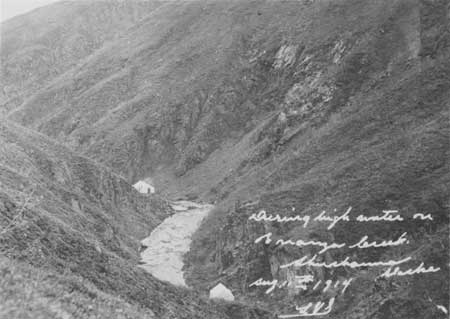

| Fig. 30. A flood on lower Bonanza Creek, August 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

When the anticipated discoveries failed to materialize, many residents left the region. Some, like postmaster Theodore Kettleson, went to Fairbanks, in route to the new diggings along the Tolovana River. Others moved to the Nizina district. A few even headed for the coast. Tony Dimond was one of the latter. Failing to make any money, Dimond resigned his position as commissioner and returned to Valdez. [73]

Both individuals, however, were soon replaced. The government appointed George R. Goshaw as postmaster and George E. Hill as commissioner. Hill, however, served only briefly before being succeeded by J. J. Finnegan. [74]

In August heavy rains disrupted mining activity throughout the region. Due to its more extensive development, Bonanza Creek was hardest hit. Flood waters destroyed one of Hamshaw's dams, and damaged flume sections or sluice boxes belonging to virtually every other outfit. Best, for example, reported that "it looked like a hurricane struck No. 7, with flumes, sluice boxes, [and] lumber . . . scattered everywhere." Lacking sufficient time and materials to rebuild, many operators were forced to prematurely end their 1914 season. [75]

Despite such setbacks, 1914 was a very successful year. The area's miners recovered 12,094 ounces of gold, or about a quarter of a million dollars. Eagerly anticipating the coming season, around two hundred chose to winter in the district. Most stayed in Chisana City. [76]

|

| Fig. 31. Louis Schonborn's store in Bonanza City, 1914. Zacharias Collection, courtesy Alaska State Library and Archives. |

One such resident was fifty-year-old Louis K. Schonborn, a well known Dawson City hotel operator during the Klondike rush. Reaching the Chisana district too late to locate a productive claim, Schonborn instead established a second-hand business, reselling outfits purchased from busted stampeders. While he located his first shop in Bonanza City, he soon moved eight miles down Chathenda Creek to the larger community of Chisana City. [77]

On December 26, 1914, Schonborn disappeared. When local authorities finally organized a search, they found his body in a vacant cabin about a quarter of a mile west of town. He had been shot twice and robbed, the district's only recorded murder. [78]

Area residents were predictably outraged. Puzzled by the fact that Schonborn had failed to lock his store, many believed that he had left with a friend or at least an acquaintance. Circumstantial evidence suggested that a popular prospector named Jimmy Kingston had committed the crime and he was duly arrested. Deputy Marshal Frank Hoffman and George R. Goshaw transported Kingston to Valdez, where he was held until the Grand Jury convened the following September. The Grand Jury, however, ultimately cleared Kingston, and Schonborn's murder was never solved. [79]

|

| Fig. 32. Mining near the head of an unidentified creek in the Chisana district, c. 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Chisana City remained viable for another year. During the summer of 1915, it still contained at least eighteen businesses, including lodging houses, saloons, and stores. The turnover of federal officials, however, continued. Resigning as U.S. commissioner, J. J. Finnegan was replaced by Tony Dimond's former assistant, Tony McGettigan [80]

As in previous years, most mining occurred on Bonanza Creek. Fred Best and Don L. Greene reported a fair return from their operation on No. 3; Joe McClellan, Robert W. Wiley, and a crew of five sluiced the upper end of No. 3 Fraction; Fletcher Hamshaw's twelve-man crew finished mining No. 4 and moved up to the lower end of No. 5; Max Altman and a nine man crew made several cuts on the lower end of No. 6; Edward "Shorty" Briggen, a miner named Hocker, and five employees mined No. 7; John Ludwig and his partner sluiced on No. 7 Fraction, which had been successfully worked by Andy Taylor the previous year; Jim Hagen and a man named Smedley mined No. 8; Robert M. Clark mined the lower end on No. 10; and James H. Murie worked eleven employees on upper No. 10. [81]

Billy James experienced a busy season. He and a crew of seven constructed a one-thousand-foot-long flume to transport water from Coarse Money Creek for hydraulic mining on Bonanza No. 9. Then he and N. P. Nelson began the process of extending the ditch, crossing from the right to the left limit of the creek at Bonanza No. 6 and continuing downstream all the way to Bonanza No. 4. [82]

|

| Fig. 33. A Fourth of July footrace at Hamshaw's camp, 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Dud McKinney also enjoyed a productive year. Two laymen, named Huntley and Moore, leased the lower part of his No. 11 claim, while McKinney and his crew mined the upper. Although his lessees experienced a disappointing season, McKinney found good pay, including some fifty-dollar pans. McKinney, however, suffered tragedy as well. On July 4, his old friend George Myers collapsed and died while visiting Bonanza No. 10. After the funeral, Myers was buried on the adjoining bench. [83]

Miners also worked claims further up Bonanza Creek. Alfred T. Wright and a miner named Anderson, for example, worked the upper end of No. 11 Fraction; George Bittner and a partner operated No. 12; James, Eagan, and Ryan examined No. 13; and John Nichols prospected Bonanza No. 17 for Chisana City store owner Sam Shucklin. [84]

Little Eldorado Creek and its tributaries were mined just as intensively as Bonanza. Two of Hamshaw's laymen, Andy Johnson and a miner named McGovern, worked the upper left limit of No. 1; Carl Whitham and ten employees operated No. 2; William "Billy" McLennan and six men mined No. 3; Charles Range and George Stone worked Bud Sargent's claim at Skookum Creek No. 1; George Woodman and a partner named Deffinbaugh mined Skookum Creek No. 2; and W. E. Nelson examined Nos. 3 and 4 on Snow Gulch. [85]

|

| Fig. 34. Splitting firewood at Hamshaw's bunkhouse, July 1914. Stanley-Mason Collection, courtesy Tacoma Public Library. |

Other area creeks received some attention. At least three miners worked parts of Big Eldorado Creek: Montgomery and Ketching sluiced No. 4 Below Upper Discovery while Richard Bell mined No. 3 Below. Eagan and company worked No. 1 on Coarse Money Creek; Louis McCallum, a miner named McNutt, and George Tweedale sluiced Shamrock Creek; Aaron Nelson prospected Canyon Creek; E. J. "Jack" Costello examined Lucky Pup; Bastell, Lewis, and Munsell mined No. 3 Below on Gold Run Creek; Dan Ryan sluiced Poorman Creek; and Wagner and Hill prospected Sargent Creek. [86]

Despite all this activity, by season's end it was clear that the Chisana was a declining district. Its gold production, for example, had fallen well below 1914 levels, with miners recovering only 7,740 ounces or about $160,000. Employment was also down. Chisana's seventeen active mines only fielded about 110 men. Having experienced a discouraging year, most miners left that fall, with only about fifty choosing to winter in Chisana City. [87]

These miners, however, remained committed to the district. Some contracted with freighter Sidney "Too Much" Johnson that October to reestablish the Hazelet trail. Billy James made the largest contribution, donating $500 cash and one man's labor, estimated to be worth an additional $300. The Alaska Road Commission supported the project as well, granting $500 toward the effort. Even McCarthy merchants participated, adding another $250. Anxious to see the job completed, James promised that any additional costs would be paid by "the people in the Shushanna." [88]

Some local residents would have been smart to leave. Fred Best's diary records the death of a friend in March 1916:

Heard today that little Fritz, who went to North Fork [of the White River] with Carl [Whitham] and I, was found frozen to death over on North Fork Island. He was over there when I came in from hunting and got caught out and froze. [89]

Fritz's death was not the only excitement that spring. On April 10, Robert K. Hover's store in Bonanza City caught fire, but quick action by local residents managed to save it. [90] Billy James experienced some difficulties as well, losing one of his horses down a glacial crevasse. [91]

The district's miners received more welcome news the following month. Louis McCallum, Edward McMullen, George Tweedale, W. A. Biglow, L. McAllister, Tony McGettigan, and Fred Nelson reported making a new discovery on Foley Creek, a tributary of Notch Creek about twenty miles west of Chisana City. The men extracted over four feet of paydirt from the bottom of their ninety-foot shaft before striking water and being driven out. The strike generated a great deal of excitement, but Foley Creek proved to be another bust. Although prospectors blanketed the area with over a hundred claims, it never produced any significant amount of gold. [92]

That summer, the area's mining activity dwindled even further. Now it contained only twelve mines, employing a total of forty men. While approximately thirty-five others continued to prospect in the vicinity, conditions deteriorated. A draught, for example, seriously hampered their sluicing operations. Gold production consequently fell to just $40,000, a 75 percent decline. [93]

As in past years, most activity focused on Bonanza Creek. Having retrieved their claims from Fletcher Hamshaw, Billy James and N. P. Nelson attempted to increase their output by installing a thirty-five-ton hydraulic plant. It, unfortunately, remained unable to operate due to the lack of water. [94]

Other claims on Bonanza were also active: Andy Taylor and Joe McClellan reported a good cleanup from No. 3; Fred Best and Don Greene worked No. 7; Jim Murie and Jack Costello mined No. 10; Al Wright and a miner named McNutt operated No. 11; and Lewis V. Stanley prospected on the stream as well. [95]

Several miners worked property on Little Eldorado. Billy James and N. P. Nelson operated No. 1; Carl Whitham mined both No. 2 and No. 2 Fraction, as well as an adjoining claim on Snow Gulch, one of Little Eldorado's northern tributaries; and Joe McClellan and Charles Fogelberg worked a claim on Bug Gulch, another branch of Little Eldorado. [96]

A tributary of Glacier Creek also received some attention, with Ned Hill and a man named Jensey operating a claim on Sargent Creek. [97]

Miners excavated two deep pits during the previous winter, on Skookum and Gold Run Creeks. The one on Gold Run appears to have been at least partially successful, for in March, the reports of a strike precipitated a small rush from McCarthy, Dawson City, and Whitehorse. Oscar Erickson began digging near Dry Gulch as well, but with tragic results. That fall, his friends found him dead in his shaft. [98]

Like many of his fellow miners, Fred Best usually wintered in the district, passing his time by trapping and hunting. He also frequently visited Bonanza City, where he spent many pleasant evenings visiting friends and playing cards. Only once or twice a year did he bother to travel across the Wrangell Mountains to the more urban community of McCarthy, and such journeys were never easy:

At dawn it was still snowing and blowing so hard that it was impossible to see more than a few yards ahead, but we started for the summit anyway. We all knew the trail, and knew there would be crevasses, some of them hundreds of feet deep, to cross. The men struggled on, the dogs worked valiantly, and we got over safely, so we kept going the thirty-five miles to town. I fell in one crack, but the dogs pulled me out. It was a long, hard day, and we were all four tired out--but glad to get over the summit. [99]

Best was not always quite so lucky. That November, for example, he barely survived a local jaunt.

I started back to get the other sled. Snow deep. Could not get to it and started back. Got lost. Could not see my trail. Dark. Hitched myself up to dogs and late at night got to little tent all in. No grub or ax. I broke wood with my hands and kept fire going all night. The dogs saved me. About 9 feet of snow. I was all in and it was the narrowest I ever came to perishing. I laid down several times but would get up and stagger on behind the dogs. God bless them. It was a narrow call I tell you. [100]

The conditions during 1917 were very similar to the previous year, with both the population and mineral production continuing to decline. Eleven mines now employed forty-four men, producing 1,935 ounces, or about $40,000 in gold. [101]

Most of the mining activity occurred on Bonanza Creek. Andy Taylor and Joe McClellan mined No. 2; Tony McGettigan and Bob Hover worked No. 2 Bench; Fred Best and Don Greene mined Nos. 3 and 7; a partnership composed of Billy James, Matilda Wales, N. P. Nelson, and Billy Johnson operated Nos. 4, 5, 6, and 9; Dud McKinney worked No. 8; Ed McMullen and Nelson mined No. 10; and Al Wright worked Nos. 11 and 11. [102]

Several other claims were also active. Billy James's syndicate operated Little Eldorado No. 1; Carl Whitham mined Little Eldorado No. 2; Bud Sargent and D. Percy Thornton worked Skookum Creek; J. E. McCabe, E. R. Behling, and Blas Joseph "Joe" Davis operated Big Eldorado No. 3 Below; Shorty Briggen mined Big Eldorado No. 2 Below; James "Windy Jim" McDonald worked Gold Run No. 2; and Virgil and Lee Catching mined Gold Run No. 3. [103]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

wrst/chisana/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 21-Mar-2008