.gif)

Historic Roads in the National Park System

MENU

II— TERRA INCOGNITA:

The Raynolds Expedition of 1860 (continued)

REPORT

Detroit, 1867

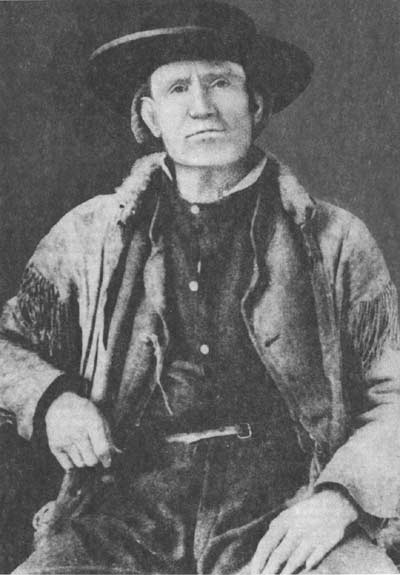

Beyond [the tributaries of the Yellowstone River west of the Big Horn] is the valley of the upper Yellowstone, which is, as yet, a terra incognita. My expedition passed entirely around, but could not penetrate it. My intention was to enter it from the head of Wind river, but [a] basaltic ridge . . . intercepted our route and prohibited the attempt. After this obstacle had thus forced us over on the western slope of the Rocky mountains, an effort was made to recross and reach the district in question; but, although it was June, the immense body of snow baffled all our exertions, and we were compelled to content ourselves with listening to marvellous tales of burning plains, immense lakes, and boiling springs, without being able to verify these wonders. I know of but two white men who claim to have ever visited this part of the Yellowstone valley — James Bridger and Robert Meldrum. The narratives of both these men are very remarkable, and Bridger, in one of his recitals, described an immense boiling spring that is a perfect counterpart of the Geysers of Iceland. As he is uneducated, and had probably never heard of the existence of such natural marvels elsewhere, I have little doubt that he spoke of that which he had actually seen. The burning plains described by these men may be volcanic, or more probably burning beds of lignite, similar to those on Powder river, which are known to be in a state of ignition. Bridger also insisted that immediately west of the point at which we made our final effort to penetrate this singular valley, there is a stream of considerable size, which divides and flows down either side of the water-shed, thus discharging its waters into both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Having seen this phenomenon on a small scale in the highlands of Maine, where a rivulet discharges a portion of its waters into the Atlantic and the remainder into the St. Lawrence, I am prepared to concede that Bridger's "Two Ocean river" may be a verity. Had our attempt to enter this district been made a month later in the season, the snow would have mainly disappeared, and there would have been no insurmountable obstacles to overcome. I cannot doubt, therefore, that at no very distant day the mysteries of this region will be fully revealed, and, though small in extent, I regard the valley of the upper Yellowstone as the most interesting unexplored district in our widely expanded country.

Wednesday, May 30 [1860] — Passing over the hills from our last night's camp (on Otter creek), we reached the valley of Wind river after travelling about a mile. We made four crossings during the day's march, this being necessary to follow the most feasible road.

Toward the close of the day we crossed a high spur, from the summit of which we obtained a fine view of the valley. To our front and upon the right the mountains towered above us to the height of from 3,000 to 5,000 feet in the shape of bold, craggy peaks of basaltic formation, their summits crowned with glistening snow. Upon our left smooth ridges clad with pine rose to nearly equal height, while behind us lay the various-hued bluffs, amid whose singular and picturesque vistas we had for days been journeying. Through the valley, in the centre, the stream could be seen placidly winding its way, a subduing element in the grandeur of a scene whose glories pen cannot adequately describe and only the brush of a Bierstadt or a Stanley could portray on canvas.

About the middle of our day's march we passed the last of the "washed lands." Above that point large boulders cover all the surface of the hills, those upon the north being basaltic and on the south granite.

Our camp is on the south fork of the stream about two miles above the Upper forks, and at the base of the mountains. From this point we propose crossing the dividing line to the waters of the Pacific. It was my original desire to go from the head of Wind river to the head of the Yellowstone, keeping on the Atlantic slope, thence down the Yellowstone, passing the lake and across by the Gallatin to the Three Forks of the Missouri.

Bridger said at the outset that this would be impossible, and that it would be necessary to pass over to the head-waters of the Columbia, and back again to the Yellowstone. I had not previously believed that crossing the main crest twice would be more easily accomplished than the transit over what was in effect only a spur, but the view from our present camp settled the question adversely to my opinion at once. Directly across our route lies a basaltic ridge, rising not less than 5,000 feet above us, its walls apparently vertical with no visible pass nor even canyon.

On the opposite side of this are the head-waters of the Yellowstone. Bridger remarked triumphantly and forcibly to me upon reaching this spot, "I told you you could not go through. A bird can't fly over that without taking a supply of grub along." I had no reply to offer, and mentally conceded the accuracy of the information of "the old man of the mountains."

|

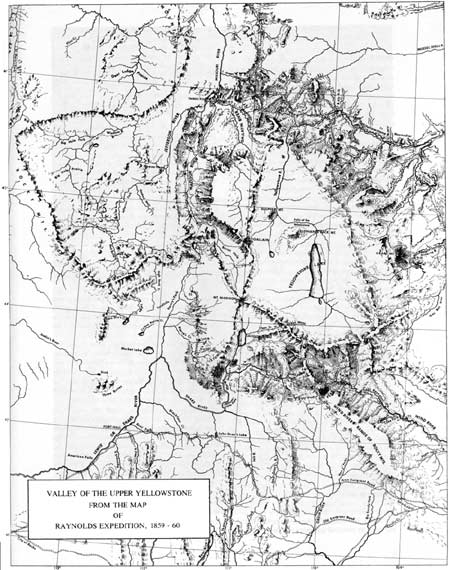

| Valley of the Upper Yellowstone, from the map of Raynolds Expedition, 1859-60. (National Archives) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

After dinner Dr. Hayden and myself rode out to the basaltic ridge, being anxious to examine it more minutely. Passing down the stream about a mile we effected a crossing, but not without getting both our horses mired and ourselves drenched, the results of over-confidence, as we had become so accustomed to hard bottom that we plunged into the stream without a thought of finding mud, and with difficulty avoided serious consequences from our mistake.

On reaching the North fork we found it impossible to effect a crossing, though the stream was only a few rods wide, until we had travelled up it for not less than six miles. Here we found the faint traces of an old lodge trail, which led us to a point at which the bottom was firm enough to enable our horses to obtain a passable footing. The North fork, for 10 or 12 miles above the upper forks, flows through a marsh about a mile in width, which at no very distant day has been a lake, and, in this marsh and the hills immediately surrounding, the stream seems to rise.

After the last crossing we rode rapidly over the hills, passing some of the finest grass yet seen, and finding snow upon all sides. Upon setting out we had selected a perpendicular crag that we determined to reach, and at length we arrived at a point from which we supposed we should be able to do so without further trouble. The cliff was not more than a mile off, but between us and it we found a deep ravine filled with a thick growth of scrubby pines, which was impenetrable at such a late hour in the day. We were, therefore, compelled to retrace our steps without effecting our object. I felt well paid, however, for the afternoon's work, as we obtained a fine view of the crest of the mountains entirely around the head of Wind river, forming a natural amphitheatre which cannot be excelled.

Throughout our entire ride we saw abundance of buffalo "signs," showing that they had been here recently, and tending to confirm a statement I have frequently heard that the Snake Indians keep the buffaloes penned up in the mountain valleys, and kill them as their necessities require. Our camping ground for the night is evidently one much used, as the remains of numerous lodges and hundreds of lodge poles cover the ground, and it is evident that a camp at this point would effectually "pen" anything not winged that should chance to be in the valley above it.

Game is certainly abundant in the valley, and during our return ride we came upon an immense animal feeding amid the long grass at a distance of but 250 or 300 yards. We supposed it to be a buffalo, but upon its seeing us and rising we discovered that it was an enormous bear, whose equal for size I have never seen. As we were armed only with revolvers we did not molest it, nor did it seem in the least disconcerted by our presence. Antelopes are also numerous, and we saw many bands of at least 40 or 50. From the marshes close by immense flocks of ducks and geese were constantly rising.

We reached camp at dark, and just before a drenching shower, after a brisk ride of over 20 miles. The regular day's march had been 14-1/2 miles.

Thursday, May 31 — We started at 7 o'clock, elated at the prospect of making our next halt upon the Pacific slope of the mountains. Bridger said that our camping ground for the night would be upon the waters of the Columbia, and within five miles of Green river, which could be easily reached. I therefore filled my canteen from Wind river, with the design of carrying the water to the other side, then procuring some from Green river, and with that of the Columbia making tea from the mingled waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of California, and the Pacific — a fancy that the sequel will show was not gratified.

Our route bore up the point of a spur that reached the valley at our camp, and in some localities the road was rather steep, but on the whole our progress was good, and we advanced nearly three miles and ascended about 1,000 feet in the first hour. Then following the ridge, we had a gradual ascent and a tolerable good road for three or four miles among stunted pines, reaching at last a large windfall, which it was necessary to pass directly through, a programme involving much labor and the liberal use of the axe.

We then commenced another rapid ascent and soon found ourselves in the snow. By making our horses take the lead by turns we forced our way through, and finally stood upon the last ridge on the Atlantic side of the dividing crest. A narrow but deep valley separated us from the summit, the snow in it being too deep for an attempt even at crossing.

Turning to the left to avoid this ravine, and picking our way through thick stunted pines, we soon found ourselves floundering in the snow. Bridger, for the first time, lost heart and declared that it would be impossible to go further. To return involved retracing our steps fully half way to the Popo-Agie, then turning north into the valley of the Big Horn, and perhaps following the route of Lieutenant Maynadier, to the Three Forks of the Missouri — a course plainly inadmissible until every other hope had failed.

|

| Jim Bridger, 1804 - 1891. (National Archives) |

I therefore determined to reconnoitre myself, and if possible find some escape from our dilemma. Dismounting, I pushed ahead through the snow, which was melting rapidly, and rendered travel both difficult and perilous. At times the crust would sustain my weight, while at others it would break and let me sink, generally up to the middle, and sometimes in deep drifts up to my shoulders. In some instances I was able to extricate myself only by rolling and stamping, and in many places I was compelled to crawl upon my face over the treacherous surface of the drifts. After great labor I found myself alone on the summit of the Rocky mountains with the train out of sight.

An investigation of the topography of the surrounding mountains convinced me that if the party could reach this point the main difficulties of the passage would have been surmounted, and I therefore started to return and pilot them through. Following my own tracks for nearly a mile I came upon them, and found that they had followed me slowly.

My attendant, who was leading my horse, stated that he should think they had advanced two or three miles since I left them, making the distance I had pushed forward alone some three or four miles. I found myself very much exhausted, and my clothes saturated with snow-water, but I succeeded in guiding the party through and at last reaching the summit of the crest. The descent upon the south side was gradual, but very difficult, the snow being deep, while at the few points at which it was gone the ground was a perfect quagmire, and it was not until we had advanced some six miles from the summit that we found a scanty supply of grass upon which we could encamp in the midst of pines and snow.

The day's march was by far the most laborious we have had since leaving Fort Pierre [South Dakota, the starting point of the expedition]; and wet and exhausted as I was, all the romance of my continental teaparty had departed, and though the valley of Green river was in plain sight I had not the energy to either visit or send to it.

Our last night's camp was at an elevation of 7,400 feet above the sea. The summit of this pass is very nearly 10,000 feet, and our camp to-night is 9,250 feet, so that the whole day has been spent in an atmosphere so rarified that any exertion has been most exhausting.

The weather has been a mixture of smiles and tears. Two or three flurries of snow passed over us attended with thunder, while at times the sun shone out brightly, renewing our life and vigor.

To the left of our route and some 10 miles from it rises a bold conical peak, 3,000 or 4,000 feet above us. That peak I regard as the topographical centre of the continent, the waters from its sides flowing into the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of California, and the Pacific ocean. I named it Union peak, and the pass Union pass.

Friday, June 1 — I was anxious to give our poor animals all the opportunity to graze that was possible, and did not, therefore, leave camp until nearly nine o'clock. We are now on waters flowing westward and into a branch of Lewis fork, which Bridger says is known to the trappers as Gros Ventre fork, the Gros Ventre Indians having been commonly in the habit of passing by this valley in their annual trips across the mountains.

The ground was frozen when we started, just hard enough not to bear our horses, and the poor beasts breaking through the crust into the mud, had as difficult travelling as could be well imagined. About a mile from camp we crossed a little rivulet not more than 18 inches wide, flowing between perpendicular banks four or five feet high. We endeavored to make the animals jump across, but four of them got in and had to be lifted out.

The valley soon became quite narrow, and, the stream commenced a rapid descent over a rocky bed. Winding our way down the hill-sides over the rocks or through the mud, some four miles, we reached a bold clay bank 75 or 100 feet high, the foot of which was washed by the stream. A narrow bridle-path led over it, along which our pack animals passed in safety, but the odometer wheels could not be kept upright even with the aid of ropes, but rolled over, carrying the mules with them, bringing up, at last, at the water's edge, where we left them for the time.

At the end of only a six-miles' march, we encamped upon a small tributary of Gros Ventre fork, having descended about six hundred feet, carrying us below the greater part of the snow and into pasturage that was much better than at our previous camp, though by no means good, the new grass not having yet started. Two or three snow-storms passed over us during the day, although the sun was shining at the time.

After getting into camp, the odometer wheels were sent after, and brought in by making a long detour on the south side of the stream.

My guide seems more at a loss than I have ever seen him, and after reaching camp he rode in advance to reconnoitre, and returned saying, "it would be necessary to make a short march to-morrow," which I do not regret, as our animals are greatly broken down.

Saturday, June 2 — The ground was covered with snow this morning. The sun shone out brightly when the herd was brought up, but, by the time we were prepared to start, snow was again falling rapidly. Crossing the stream, which is here about forty feet wide and two and a half deep, we continued down Gros Ventre fork, our course being north of west. The road was better than any before found on this side of the mountains, but the rapidly falling and melting snow caused mud that retarded us somewhat.

After a march of but three miles, Bridger advised a halt, as he did not know of another good camping ground within accessible distance. The grass is improving in quality, and I hope the rest of the Sabbath will be of essential benefit to our broken-down animals. Our object now is to keep as near to the dividing crest as possible and recross, as soon as we shall be able, to the headwaters of the Yellowstone.

The animal life of this region differs essentially from that on the Atlantic slope. Even in Wind River valley many birds new to us were seen, and Dr. Hayden and his assistants have been very busy collecting specimens of all kinds. Three or four squirrels previously unknown to us, double that number of birds, and a large and new species of rabbit have been obtained. Yesterday, Bridger shot a "mule deer," and the day before our hunter killed one on the eastern side of the crest of the mountains, a locality out of their usual geographical limit.

Sunday, June 3 — We passed the day quietly in camp. The sky has been cloudy, and we have been visited by occasional showers.

Monday, June 4 — Our course to-day has borne nearly northwest, and we are no longer following the course of the stream, but crossing the ridges separating its different branches. The road was found to be almost impassable. The snow had scarcely gone, while the ground was perfectly saturated with water. The depth of the mud, and the exhausted condition of the animals, made marching almost impossible.

A spirit of insubordination and discontent was also manifest among the men, showing itself openly in their apparent determination to abandon all further efforts to bring along the odometer wheels, which they permitted to turn over five times in about half a mile. It was with the greatest difficulty that I succeeded in enforcing discipline and inducing the men to continue the faithful discharge of their duties. A long march was plainly out of the question, the spirit of the party, the condition of the beasts, the state of the roads, and the scarcity of grass, all forbidding it. We halted therefore for the night after advancing all but eight miles.

Tuesday, June 5 — We left camp at 7-1/2 a.m., starting off rapidly to the northwest across the spurs running down to Gros Ventre fork. The hill slopes were not as steep as those passed over yesterday, and had it not been for the mud the road would have been good. As it was, the animals labored hard, sinking over the fetlock at every step. A month later in the season, however, there would probably be no especial difficulty encountered in travelling here, the late rains being chiefly responsible for our troubles. Crossing one or two inconsiderable streams, at about 10 miles from our morning's camp we reached the valley of what was supposed to be another branch of Lewis river, but which subsequently proved to be a northern fork of the Gros Ventre. Here the mud became far more impassable than before, while our labors were greatly augmented by occasional banks of snow through which we were compelled to force a way.

After travelling some two miles in this valley, further progress in it became impracticable, and an attempt was then made to push on along the side of the mountain. There, however, among the pines the snow was found in impassable banks, while the open ground between presented even more obstruction than the snow itself, the soil being loose, spongy and saturated with moisture, so that the animals were constantly and helplessly mired.

I counted at one time 25 mules plunged deep in the mud, and totally unable to extricate themselves. To go on was clearly impossible, and, as we were now above grass, to remain here was equally out of the question. The only course left, therefore, was to return, and we retraced our steps for about two miles, and pitched our tents at a point where our animals could pick up a scanty subsistence.

After getting into camp Bridger ascended the summit of a high hill to obtain an idea of the country, and returned after dark with far from a favorable report. Nothing but snow was visible, and, although he seems familiar with the locality, it is evident that he is in doubt as to what it is best that we should next attempt. As I am exceedingly anxious to reach the upper valley of the Yellowstone, after a full discussion of the question in all its bearings with him to-night, it has been determined to make to-morrow a thorough examination of the mountains and pick out some path by which we may, if possible, find our way across them, and accomplish our purpose.

Wednesday, June 6 — Leaving the party in camp, I started with Bridger this morning, in accordance with our last night's arrangement, to ascertain if it was possible by some means to cross the mountain range before us. Following up the stream we soon reached the limits of our yesterday's labors, and seeing a westerly fork which apparently headed in a low "pass" that looked promising, we determined to explore it.

|

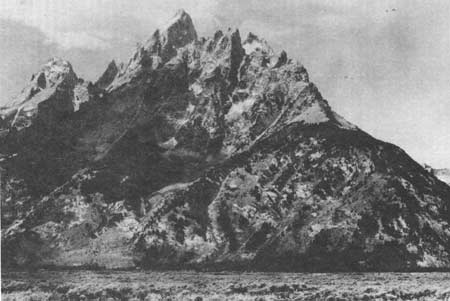

| The towering Teton Range in northwest Wyoming is just south of Yellowstone Park. (National Archives) |

Before reaching this fork we experienced great trouble in picking our way around snow drifts and through mud. After leaving the main stream the ground rose rapidly and the hillsides were covered with a dense growth of stunted pines, under which we found snow in abundance. Some of the banks were not so deep as to prevent our horses from plunging through them, but others had to be trodden down before we could effect a passage. The labor was of course excessive, but by perseverance the summit was at length reached.

Bridger immediately declared that we were on the wrong route and that our morning's labor had been wholly useless. This was evident by the course of the ravine upon the other side of the ridge, which tended so far to the southward as to show that the drainage was still towards the Pacific, and that we had expended our efforts in climbing a spur. We therefore returned to the valley and ascended the main stream, which carried us further to the eastward, and at first looked much less promising than the other.

After forcing our way through the snow-banks along the banks of the stream for about a mile, we reached a point where, for three-quarters of a mile above, the valley was comparatively wide, being bordered by steep cliffs, cut in deep gorges, filled with snow. The neighboring hillsides were clad with snow, and the level valley was covered to a uniform depth of from eighteen inches to two feet, without the slightest appearance of ever having been crossed by man or beast.

Bridger at once seemed to recognize the locality, saying, "This is the pass." Our own exhaustion, however, as well as that of our horses, was too great for any further attempts to-day, and we therefore returned to camp, determined to make another and final effort to reach the summit to-morrow.

Thursday, June 7 — I started this morning with a party of nine, all told, to make the last attempt to find a solution of the difficult problem imposed upon us. My companions were the guide, Bridger, Dr. Hayden (naturalist), Mr. Hutton (topographer), Mr. Schonborn (artist), and four men. One of the mules, however, fell into the stream soon after starting and was nearly lost, and we were compelled to send it back to camp, with its rider.

The rest of the party pushed on in our tracks of yesterday, without special trouble, till we reached the valley discovered at the close of our labors of the previous day. Here we encountered great obstacles. The deep snow in the numerous gorges rendered progress along the hillside impossible, and compelled us to keep close to the stream in the valley, the descent into which was accomplished with much trouble. Our route here was crossed by side gullies from two to four feet in depth, entirely invisible beneath the uniform surface of the snow, and into which we tumbled, and out of which we floundered in a style at once ridiculous and exhausting. We partially remedied this, at last, by probing the depth of the snow ahead by rods, and by this simple expedient saved ourselves much labor and annoyance. We ultimately reached the upper end of the valley, and by a steep climb over the snow scaled the last ascent and stood again upon the dividing crest of the Rocky mountains.

It did not require long to decide that further progress was impracticable. From the southward we had already passed over ten or fifteen miles of snow, but then we knew that there was a limit to it easily reached. To the north, or the direction in which our route from this point would lie, the view seemed almost boundless, and nothing was in sight but pines and snow. To bring the party to where we stood was next to impracticable, but this I had determined to attempt, if there were any hopes of getting through the snow on the Yellowstone side of the mountains. My fondly cherished schemes of this nature were all dissipated, however, by the prospect before us, as a venture into that country would result in the certain loss of our animals, if not of the whole party.

I therefore very reluctantly decided to abandon the plan to which I had so steadily clung, and to seek for a route to the Three Forks of the Missouri, by going further to the west and passing down the valley of the Madison. After taking in our fill of the disheartening view we returned to camp, to commence the execution of our new project on the morrow.

From William F. Raynolds, "Report on the Exploration of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, in 1859 — '60." S. Exec. Doc. 77, 40th Cong., 1st sess. (1868).

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Nov 15 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

baldwin/chap2a.htm

Top

Top