.gif)

Historic Roads in the National Park System

MENU

VI— THE GRAND LOOP:

A Legacy of Dan C. Kingman (continued)

REPORT

Mammoth Hot Springs, 1886

An act of Congress, approved March 3, 1883, appropriated $40,000 for every purpose and object necessary for the protection, preservation, and improvement of the Yellowstone National Park, including compensation of the superintendent and his assistants. The salaries of these persons were fixed by the act, and amounted in the aggregate to $11,000. The act provided that the balance of the appropriation should be expended in the construction and improvement of suitable roads and bridges within said park, under the supervision and direction of an engineer officer detailed by the Secretary of War.

This was the beginning of systematic road construction in the Park. Prior to that Congress had made a number of small appropriations for the protection and improvement of the Park, and a portion of this money has been expended by the different superintendents in opening roads and trails. These roads and trails made it possible to reach the various points of interest in the Park, but the work done was temporary and the locations were faulty, and thus were of little or no value in the general plan of permanent improvement.

In July, 1883, I was designated by the Secretary of War to carry out the provisions of the act before referred to, and I went to the National Park. I found the following roads in existence then:

A road from the western boundary to the Forks of the Fire Hole River, about 20 miles in length.

A road from the last-named point to Mammoth Hot Springs, about 40 miles.

A road from Mammoth Hot Springs to the mouth of the Gardiner River, about 4 miles.

A road from Mammoth Hot Springs eastward via Baronett's Bridge towards Clark's Fork Mines, about 50 miles.

A road from the Forks of the Fire Hole River to the Upper Geyser Basin, about 10 miles.

A road from the same point to the Falls of the Yellowstone River, about 28 miles.

A branch from this road to the outlet of the Yellowstone Lake, about 8 miles.

In all about 160 miles of road, over which one could pass with a wagon under favorable circumstances with more or less difficulty.

In addition to this there were many miles of blazed trails, passable on horseback.

The roads . . . were all very bad — barely passable even in good weather. The lack of means and the desire to reach in some way the various points of interest had forced those in charge to be guided in their location by the question of first cost. Very crooked as well as very hilly roads were the result. In general, only trees enough have been cut down to permit the passage of a single wagon, and the stumps were left standing well above ground.

For miles the roads were so narrow that teams meeting had great difficulty in passing, and an outrider was a necessary adjunct of a train. Such bridges as had been constructed were covered with small poles, and there were long stretches of badly built corduroy that were almost impassable when wet.

The side-hill cuttings were generally supported on the outside by small logs and brush, and were necessarily very temporary in character. No attention had been paid to drainage, and the water ran in the middle of the roads, or stood in pools in the low places.

The principal points of interest, and those which the public were most anxious to visit, were: The Mammoth Hot Springs, the Norris Geysers, the Lower Geysers (at the Forks of the Fire Hole River), the Upper Geysers, the Yellowstone Lake, and the Falls and Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, and it will be seen that the existing roads enabled the tourist to visit them all.

The approaches are, first: Via the Northern Pacific Railroad to Livingston, Mont.; thence by the Park Branch Railroad to Cinnabar, Mont., from which it was about 8 miles to Mammoth Hot Springs. And second: Via the Utah and Northern Railroad to Beaver Canyon, Idaho; thence by stage up the valley of the Madison River to the Fire Hole Basin, about 100 miles. By far the greater number of travelers chose the former route.

Such was the condition of affairs at the time of my arrival in the Park.

|

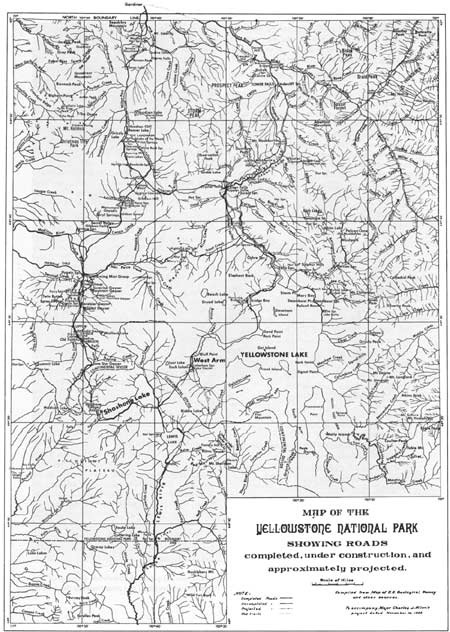

| Map of the Yellowstone National Park. (National Archives) (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The project that I have prepared for the improvement of the Park called for the construction of . . . [a 223-mile] system of roads, [which], if constructed, would enable tourists to visit the principal points of interest in the Park without retracing their steps; and to take a long or short trip, according to the time and the means at their disposal.

The route from Mammoth Hot Springs through the Norris Geysers to the Lower and Upper Geyser Basins, thence to Shoshone Lake, thence to the Yellowstone Lake, and along the lake to the outlet, thence down the river past the Mud Geysers to the Falls, thence along the brink of the Canyon, and over the shoulder of Washburn to Tower Creek and Falls and to Yancy's, and thence back to the springs, would enable persons, without retracing their steps, to visit all the principal points of interest, and would be a journey of about 150 miles.

By not visiting the lakes and going from the geysers to the falls the journey would be reduced to 125 miles, and by going from the Norris Geysers to the falls the trip would be but 80 miles.

The region embraced by the Yellowstone Park, from its high, rugged, and mountainous character, presents in varied forms and combinations almost every obstacle that nature offers to the construction of roads. There are steep mountains, dense forest, rocks, streams, canyons, and marshes, heavy rains, deep snows, besides the peculiar hot springs formations, which are very extensive, and afford the worst road material I have ever met with.

I recommended that no more bad roads be built in the Park, but that thereafter they have something of the solid, durable, and substantial quality that usually characterizes the works constructed by the Government.

I therefore proposed that all roads in the National Park should be made at least 18 feet wide and well-rounded up in the center, and provided with suitable side ditches and cross-culverts; that all trees be removed for a width of 30 feet; and on side-hill cuttings the fill to be retained by a dry stone wall, and that an ample ditch be placed on the uphill side to catch the snow-water and carry it to the natural water-courses; that all culverts be of stone or 3-inch plank; and that all bridges be well constructed of sawed lumber.

After carefully examining the country through which the roads would have to pass, I was satisfied that suitable ones could not be built for a less average cost than $1,000 per mile, nor properly maintained for a less annual outlay than 10 per cent of the first cost. In the execution of the project it was proposed to make such repairs to the existing roads as would enable them to be used till the new ones could be built; then, as the amount appropriated was very small, in comparison with the estimated cost, it was proposed to expend it on such parts of the new system of roads as would be of most direct and immediate benefit to travelers in the Park. The work was all done by hired labor, and the supplies were purchased in open market. The repairs above mentioned consisted in widening and straightening the roads, removing stones, stumps, and trees, improving the drainage, constructing turn-outs at frequent intervals, reducing slopes, repairing bridges and fords, covering corduroy with sods and earth, etc., and the cost was from $25 to $175 per mile. The roads were much improved; but they were very far from being good, even then.

In the meantime I commenced a new road from Mammoth Hot Springs to and through the canyon of the west fork of the Gardiner River, to connect with the road of the Fire Hole, at a point near Swan Lake.

At the end of the working season of 1883, I estimated that it would require $205,000 to complete the project; of this amount, $6,000 was for office and quarters; $20,000 for the road from Yancy's to Clark's Fork: . . . thus leaving $179,000 as the amount necessary for completion of the system of roads that now form the project.

The superintendent of the Park was authorized by the Secretary of the Interior to expend such portion of the appropriation as might be necessary for the protection and preservation of the Park. This reduced the amount available for roads and bridges from $29,000 to $23,570.03

The total amount that has been expended upon this work, up to [June 30, 1886, is $69,779.42].

The first [new road, from Mammoth Hot Springs to Gardiner, Montana] was begun in the summer of 1884, and was completed August 18, 1885. This is the route followed in going from the Park to the terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and is used as a freight road, as well as for the transportation of passengers. It is used by the superintendent of the Park and his assistants, and other residents of Mammoth Hot Springs, during the entire year. They receive their mail and supplies over it, and therefore, unlike most of the roads in the Park, it must be practicable at all times; in other words, it must be a winter as well as a summer road.

|

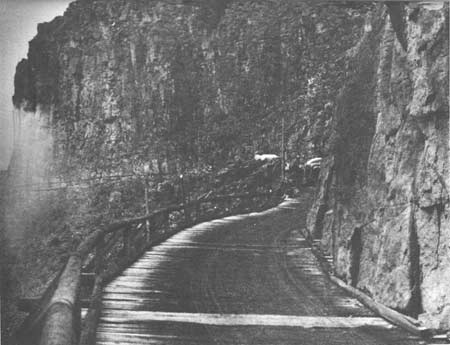

| The first road through Gibbon Canyon, shown here near Gibbon Falls, was built by the Engineers in 1885. (National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park) |

The total cost of the work was $7,750.52.

The second piece of new work (Mammoth Hot Springs to Swan Lake) was commenced in September, 1883, and finished June 12, 1885. This road was intended to avoid the worst obstacle to the entrance to the Park from the north, which was the steep hill which must be ascended in order to reach the plateau lying south of Mammoth Hot Springs, and commanding the site of the hotel some 1,200 feet. This ascent was overcome by the old road in about 2 miles, and not by a uniform grade either, but by a series of inclines so steep as to be almost impassable for a loaded wagon when the ground was wet, and dangerous to descend at all times. The new road follows up the west fork of the Gardiner River, and unites with the old one about 5 miles from the starting-point. This route, though heavily timbered, and covered in many places with rocks and bowlders, offered no serious obstacle to the construction of a road until the head of the Canyon was reached. Here, for about 1,000 feet, the rock walls approached each other, and were nearly vertical, and the little stream in the canyon had a fall of 60 feet. The walls were too high to admit of the road being carried over the top. This quarter of a mile was by far the most difficult and expensive piece of work undertaken in the Park.

At the mouth of the canyon the wall was nearly vertical, and sufficient roadway could be secured only by cutting and breaking down the solid rock over 100 feet. The cost of this would have been excessive. The road in this portion was supported by timber trestles.

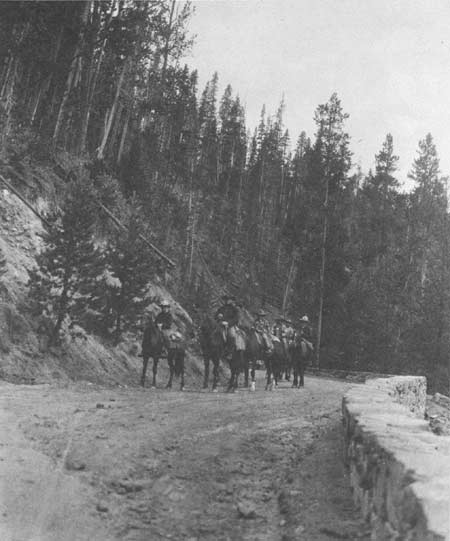

|

| A team of horses toils along old Mount Washburn Road. (National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park) |

The total length of the structure is 224 feet, and its cost was $3 per running foot. When the rock walls were sufficiently inclined the road was built entirely in excavation. At some points it was necessary to begin work 70 feet above the proposed road-bed.

The excavation of this work required the removal of over 14,000 cubic yards of solid rock, besides a very large amount of rock in a crushed and broken condition. Twelve hundred and seventy-five pounds of explosive (one-half of which was dynamite) was used in the work, and nearly 1,300 shots in drilled holes were fired. The work was accomplished without accident or injury to any one. The benefits conferred by this improvement are very marked. The distance from Mammoth Hot Springs to the Geysers and other points of interest is reduced 1-1/2 miles, and the height to be overcome in reaching the Swan Lake Plateau is reduced 250 feet. The ascent is made so gradually that loaded teams pass over the road in both directions with ease and safety, and the time required to go from Mammoth Hot Springs to points within the Park has been shortened by the improvement alone from two hours to a half a day, depending upon the team and its load. The total cost was $14,395.39.

The third new work is the road from the south end of Beaver Lake to the hotel at Norris Geysers Basin. It was begun and finished in the summer of 1885. The object of this road was to avoid a series of obstacles due to bad location.

|

| Road from Mammoth Hot Springs to Swan Lake, shown here bridging Golden Gate near Kingman Pass, built by Engineers, 1885. (National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park) |

The new location follows a lower level, giving drainage, exposure to the sun, and a soil more suitable for road covering. The total length of the section is 7 miles, and its cost of construction was $6,269.80, or about $993.62 per mile, including wear of tools, office expenses, etc.

The fourth improvement (Fire Hole to Upper Basin). This road was completed in one season (1885). Its length is 8.9 miles, and its cost was $6,042.53. It reduces considerably the distance to be traveled in reaching the Upper Geyser Basin. It is well built throughout, and its bridges and culverts are of the most substantial character. It follows the river, and is sensibly level, and as the road-bed is mostly composed of gravel that packs well, it is a very pleasant road to drive over.

The fifth new road (through Gibbon Canyon) was commenced in the summer of 1884 and completed August 1, 1885. This section, about 3 miles in length, was generally one of the worst in the Park, and was dreaded alike by drivers and tourists. It is now a good road at all times, is never muddy, and forms a stretch that drivers soon select to make up lost time on. Its total cost was $4,604.64, including a very good bridge that cost $877.

The sixth section was along the Yellowstone River, near the Falls. The improvement was made in the summer of 1884 and cost $1,919.57.

This was the condition of affairs at the beginning of the present fiscal year [1887]. Up to this time the funds for the work had been disbursed by the superintendent of the Park on my vouchers duly certified. The appropriation for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1887, amounted to $20,000, and it was provided in the act that this money should be expended under the direction of the Secretary of War.

The project for its expenditure was as follows: First, to build a wagon-road from Norris Geysers to Grand Canyon, 12 miles, cost $12,000; Second, general repairs to existing roads, $8,000.

Work was pushed vigorously on the new road, but owing to early snow-storms and bad weather it was not completed. Its total length is 11-3/4 miles. All of the trees, stumps, and rocks have been removed from the right of way, and about 9 miles have been graded. The amount expended on this work is $9,368.48, and I estimate it will require about $3,000 to complete the work. About $1,000 of this will be needed for the repair of the portion graded last fall, for, being soft, it will probably be washed a good deal. I also made thorough repairs (amounting to rebuilding) to the section of road from Green Creek along Beaver Lake and Obsidian Cliff. The work was expensive on account of the number of rock cuts, and it is very well done. The right of way is cleared for about 2-1/2 miles and it is graded and finished for about 1-1/2 miles. A very good bridge was built across the outlet of Beaver Lake. The cost of the improvement was $4,431.49.

By direction of the Chief of Engineers I submitted an estimate October 9, 1886, [of $150,000 for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1888]. This will build 100 miles of new road and repair 100 miles.

In the foregoing I made no estimate for the road from Yancy's to the boundary of the Park towards the Clark's Fork mines. This item has been omitted from the estimate since the first year of the work. About this time an effort was made to secure from Congress a right of way for a railroad through the Park to reach these mines. If this railroad was built there would certainly be no need of a wagon-road. Fortunately this bill failed each year to become a law, and now another route, that does not pass through the Park, has been found, and the matter may be regarded as settled.

I think, however, that a road should some time be built as far as Soda Butte. This is a very beautiful and interesting portion of the Park, and Soda Butte ought always to be kept up as a game-keeper's station. In regard to railroads, I need only say that I should regard their introduction into the Park, upon any pretext whatever, as a very serious detriment and injury, and I think that all true friends of the Park should oppose them by every means in their power.

It is very difficult to make plans for the improvement of the Park, on account of the uncertainty as to what its future is to be.

The law says that it is dedicated and set apart as a public park or pleasuring ground, for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. As long as its timber is preserved it is valuable as a reservoir for our two great rivers. If it were extended, so as to include winter as well as summer ranges, it might also afford a last resort and permanent abiding place for the large game of the country.

The plan for improvement which I have submitted is given upon the supposition, and in the earnest hope that it will be preserved as nearly as may be as the hand of nature left it — a source of pleasure to all who visit it, and a source of wealth to no one. If the Park ever becomes truly popular and national, it will be when the people come to know and appreciate its delightful summer climate, the wonderful efficacy of its baths and its mineral waters, as well as the natural wonders, beauties, and curiosities to be seen there; then, if there are numerous small, quiet hotels scattered here and there throughout the Park, where visitors can have plain and simple accommodations, at moderate prices, the overworked and the sick, as well as the curious, will come here, not to be awed by the great fall and astounded by the geysers, and then to go away, but will come here and remain for weeks or months, and will find what they seek — rest, recreation, and health. But if it ever becomes the resort of fashion, if its forests are stripped to rear mammoth hotels; if the race-course, the drinking saloon, and the gambling-table invade it; if its valleys are scarred by railroads and its hills pierced by tunnels, if its purity and quiet are destroyed and broken by the noise and smoke of the locomotive; if, in short, a sort of Coney Island is established there, then it will cease to belong to the whole people and will be unworthy of the care and protection of the National Government.

During the past season . . . the game, the growing timber, and the objects of curiosity and interest in the Park have been better protected than ever before; the number of visitors increases from year to year, and while there are many complaints of bad roads, poor and inadequate hotel accommodations, and high prices, I talked with none among the thousands who visited it who did not appreciate the wisdom that dedicated the National Park to its present uses, or who doubted that the Park was destined to a great and valuable future. It is not too much to say that if the Park can be preserved as it now is, subject only to such slight changes as are necessary to secure good roads and trails through it and proper hotels to insure the comfort of visitors, it will become, in time, a health and pleasure resort unequalled in the whole world. Its maintenance is of more than national importance; it is an object of direct personal interest, now and in time to come, to travelers and scientists the world over.

From Dan C. Kingman, Notes on "Construction of Roads and Bridges in Yellowstone National Park." Quoted in ARCE, 1887.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Nov 15 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

baldwin/chap6a.htm

Top

Top