.gif)

Historic Roads in the National Park System

MENU

VII— LABORS OF LOVE:

The Projects of Hiram M. Chittenden (continued)

REPORT

Mammoth Hot Springs, 1893

The work . . . was mainly done along the Yellowstone River, consisting of road completion, general repairs, and graveling, particularly at Trout and Antelope Creeks, Alum Creek, and the stretch of road along the cut bank about a mile north of Alum Creek. After the completion of this work the opening of about a mile of new road was begun along the rapids of the Yellowstone to replace the bad stretch of old road which passes through the fields at some distance back from the river. This work was carefully laid out . . . and will form probably the finest piece of work from a professional point of view, as it certainly will be the most interesting scenic route hitherto constructed. Commencing at that point of the river where it breaks into the extremely picturesque rapids which extend for half a mile above the falls, the road leaves the river just opposite the brink of the falls, forming a fitting introduction to the general scenery of the Grand Canyon. On this piece of road will be the largest bridge yet constructed in the Park. Its length is 180 feet and greatest height about 52 feet. It crosses the inlet of a small, and generally dry, tributary of the Yellowstone. It is built on a gradient of 3 feet to 100. It is composed of three decks on the plan of ordinary railroad bridges. The proper sizes of timbers have been carefully computed and the cost of the whole estimated. It will require approximately 70 M feet of lumber, a part of which we have from last year's supply, and will cost, complete, about $1,500. The only work so far done upon it is the building of the foundation to a point above high-water mark, and the hauling of about 20 M feet of lumber to the ground. It will take but little work in addition to the completion of the bridge to make this piece of road available.

The season's work was executed under considerable difficulties, which arose principally from the necessity of organizing a force in too short a time to permit of careful selection. There are always many floating laborers or tramps (for that is what they really are) who want to go through the Park and who seize the opportunity offered by the Government work to get into the Park and out again at no expense. They are utterly useless as laborers, and it is not easy, without taking greater precautions than our limited time permits, to exclude them. All the laborers are generally poorly supplied with clothing and bedding and find the frosty nights in the mountains too severe to get along with and consequently they generally remain but a little while. The problem of getting efficient help for the work in the National Park is the most serious one we have to deal with.

After the close of the tourist season I made a statistical investigation on a small scale designed to ascertain the views of the traveling public as to what will most contribute to the enjoyment of a tour of the National Park. I was led to examine this question from the fact that the hotel company, which has been seeking an electric railway franchise in the Park, had endeavored to obtain, during the summer, the signatures of all tourists who favored an electric line as a means of transportation. Of course such an expression, being entirely one-sided, could form no fair criterion as to the actual state of opinion upon the subject. For the purpose of obtaining a fair expression upon this point, and incidentally to show how little foundation there is for the opinion entertained in certain quarters that the Park road-work is practically completed, as well as to get the general impression of visitors upon the importance of the Park as a national pleasuring ground, I selected the name of one tourist for each day of the tourist season, covering all conditions of climate and travel, and sent to each the following questions: (1) What was the principal drawback to the enjoyment of your tour of the Park? (2) From the experience of your own tour would you advise your friends to visit the Park? (3) Assuming that there were a complete system of thoroughly macadamized or graveled roads in the Park, so constructed as largely to eliminate the mud and dust nuisance, and in which there should be no hills so steep that teams could not ascend them at a trot; and assuming also that there were a well-equipped electric railway covering substantially the same route, by which method would you prefer to make a tour of the Park: by [stage] coach or by [railroad] car?

|

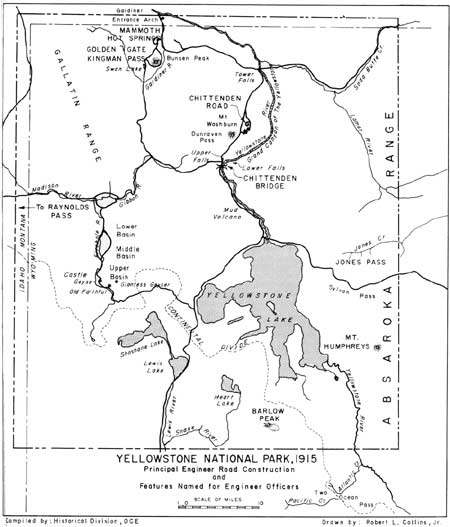

| Yellowstone National Park, 1915. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The names selected were in all cases those of strangers to myself, and were chosen from all sections of the country in order that the answers might form as fair a basis of general opinion as possible.

Of the one hundred and twenty letters sent out about twenty failed to reach their destination, owing to the defective post-office address taken from the hotel register. The answers to the rest were full and complete, quite beyond my expectation, and were the best possible proof of the deep interest which all who have seen the National Park take in that reservation. The answers nearly always contained the additional views of other members of the particular party to which the person addressed belonged, so that the aggregate of answers considerably exceeded the number of letters sent out. The tabulated result is as follows:

Answer to first question: Condition of roads, 97; hotel accommodations, 26; transportation accommodations, 17; miscellaneous, 24,; no drawback whatever, 24; no answer to question, 4.

Answers to second question: Yes, 141; no, 2; no answer, 4.

Answers to third question: By coach, 147; by car, 29.

The above answers show (1) that to the great majority of tourists the present imperfect condition of the roads, the steepness of hills, presence of mud or dust, roughness of the way, are the principal drawbacks to the enjoyment of the Park. (2) That the wonders of the Yellowstone National Park more than offset the often serious discomforts of travel. The expression of opinion upon this point was practically unanimous. (3) That tourists, by a majority of five to one, object to the introduction of electric railways into the Park. It must be stated, however, that the answers to this question were in many cases conditional upon the existence of roads such as are described in the question. It is quite certain that if the choice had been between an electric line and our present roads the vote would have been in favor of the former.

It was the third question that elicited the most interesting comments upon the Park. Many of the writers insisted at length upon the importance of keeping the Park free from corporate encroachment of any kind, especially in the introduction of any form of railroad. The use of stage coaches was considered a desirable feature of the tour. In fact, those who favored the car were in most cases those who lacked either time or physical strength for the slower and rougher method of carriage.

The whole inquiry emphasizes the importance of securing a thorough system of macadamized roads for the Park and of keeping it free from anything like railroad encroachment.

1899

The extraordinary lateness of the season — the latest known in the history of the Park — has deferred even these minor operations beyond any previous experience and has carried them into the next fiscal year. . . .

The annual repairs, including opening the roads through the snows which lay very heavy on the higher sections of the road system, were actively prosecuted during the month of June. A veritable winter climate prevailed throughout the upper Park during the first half of the month, snowstorms being of almost daily occurrence. The melting of the snows and the frequent storms left the ground in many places thoroughly soaked, at the very time when the heavy supplies for the hotels were being hauled into the Park. It has been with much difficulty, therefore, that the roads, which as yet are composed for the most part only of the soil through which they pass, have been placed in fairly passable condition in time for the opening of the tourist season. . . . The ordinary method of doing this preliminary work, based upon many years experience, is to send out parties at as early a day as practicable to shovel a passage through the deepest snows and then to follow up this work, as soon as the snow is mainly gone, with one or two considerable parties equipped for regular road work. These parties open and repair damaged culverts; repair the bridges, clear away landslides and fallen timber, smooth up the road surface with grading machines, repair retaining walls, and do whatever else is rendered necessary by the action of the elements during the long and severe winters which prevail in this region. As a general thing, fair weather follows closely upon this preliminary work and is the most important factor in putting the roads in good order. Under such circumstances, two or three weeks' work suffices to place the system in as good condition as it is susceptible of.

In other years, when the seasons are late and the snow melting and resultant storms continue after the spring traffic has opened, the problem is far more serious. The experiment has been tried this year on a small scale of posting section gangs at intervals throughout the Park, similar to those on railroads. Only moderate results are looked for, however, in this direction. The road system is not yet in a state of efficiency to make it a complete success. With macadamized pikes the system of small repairs by section crews would undoubtedly be the best, but now the repairs so often amount to actual reconstruction that small parties are incompetent to handle them. The section plan is being tried upon the urgent recommendation of several parties who understand the needs of the Park thoroughly from long residence here, and doubtless considerable benefit will result from the trial.

In addition to the current repair work, plans have been matured for the new work of the season which will be begun promptly upon the opening of the new fiscal year. This work will consist mainly in the building of a new road of about 3 miles length between Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyo., and Golden Gate. This line has been selected after several personal examinations by the officer in charge, and is now being laid out by instrumental surveys preparatory to commencement of the work.

In making up the estimates for the ensuing year in accordance with the customs and regulations of the Engineer Department, to which this work is now returned after the experiment of withdrawal during a period of four and one-half years, it will contribute to a better understanding of the magnitude and importance of the work if a brief sketch of its origin and development is given.

The discoverers of this region in 1870 found numerous trails of infrequent use, made by the Indians, passing over several of the routes now followed by the regular highways. As travelers became attracted here in the early seventies, saddle trails developed leading to the principal localities of interest. The main trail led from the Mammoth Hot Springs, via Mount Washburn, to the falls of the Yellowstone, crossing hence by the now abandoned Mary Mountain route to the Firehole Geyser Basins, where it was joined by another trail coming in from the valley of the Madison on the west. During the superintendency of Colonel Norris, 1878-1882, several wagon trails (mere passage ways for wagons, with no grading except where absolutely necessary) were built, and the present general line was opened from the Mammoth Hot Springs to the Upper Geyser Basin, with a line across Mary Mountain to the lake and canyon. In 1883 the roadwork was formally assigned to Lieut. D. C. Kingman, Corps of Engineers, by whom the project for the Park road system, as it has since been worked out, was prepared. Lieutenant Kingman himself made an important commencement to this work.

The project for a system of tourist routes to the various points of interest in the Yellowstone National Park, as proposed by Lieutenant Kingman, and slightly modified since, embraces a belt line which makes a general circuit of the Park, approaches by which the belt line is reached from various points on the Park boundary, and side roads to scattering points of interest. To these might also be added the numerous trails used mainly by scouts and troops in protecting the Park, but involving little if any outlay for construction or maintenance.

The Belt Line, as proposed, includes Mammoth Hot Springs, Norris Geyser Basin, the Firehole Geyser Basins, the Yellowstone Lake, the Grand Canyon, and the section near Tower Falls below the Grand Canyon at the northern base of Mount Washburn. Between Norris and the Grand Canyon there is a crossroad which will always be of use for freight, even when the Belt Line is complete and tourist travel no longer passes over it.

The main approaches will probably not exceed one on each side of the Park. Of these the principal one now is on the north via the Gardiner River to Mammoth Hot Springs; this is the Northern Pacific connection.

The next most important approach is from the west via the Madison Valley. The Utah Northern connection is here, although the railroad is a day's journey from the boundry of the Park.

The southern approach leads up the valley of the Snake River from the celebrated locality known as Jackson Hole, and joins the Belt Line at the Yellowstone Lake. With a southern railroad connection, this will be an important approach.

On the east there is no regular approach. There is a road to the northeast corner of the Park from near Tower Falls, but it is used almost exclusively by miners located just outside the boundary. It is probable that before many years it may be necessary to make an approach from Big Horn Basin via Jones's Pass to the outlet of the Yellowstone Lake. The necessity for such a road, however, will be contingent upon the advent of a railroad in the Basin, and it is, therefore, not included in the present estimate.

The Park itself is fulfilling the purpose of its creation beyond the expectation of its most sanguine advocates. As a refuge of the native fauna of the continent it is an unqualified success. As a resort for pleasure seekers and those interested in natural curiosities it has continually grown in public favor. Its administration, protection, and methods of caring for tourists have developed into a comprehensive and admirable system. Congress may therefore rest assured that an appropriation for the completion of the approved project of improvement of the Yellowstone National Park will be in every sense a judicious expenditure.

|

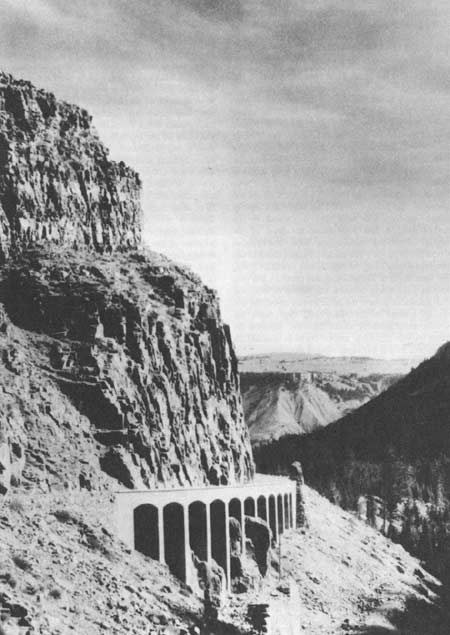

| Corkscrew Bridge on the Sylvan Pass road. (National Park Service, Yellowstone National Park) |

1900

At the close of the last fiscal year the programme of work in the Park for the ensuing season had been laid out and operations were begun as soon as the appropriation was available. The amount of the appropriation being insufficient for the work that needed to be done, it was thought best to concentrate it as far as possible on a single portion of the work and do that thoroughly, rather than scatter it in several places. After consulting with those who are best acquainted with the needs of the Park road system, it was concluded that the work which was most urgently required was the construction of a new road from Mammoth Hot Springs to the top of what is called the Golden Gate Hill.

This hill rises about 1,000 feet above the level at the Mammoth Hot Springs hotel in a distance of 4 miles. It has always been one of the most serious obstacles to travel in the Park. The first road built up the hill was what is called in that country a wagon trail; that is, a primitive road without any grading to speak of, but simply a track capable of giving passage to wagons. It reached the upper plateau through Snow Pass, about 2 miles west of Kingman Pass, in which the present road lies, and 2 miles distant from Mammoth Hot Springs. The road was almost impassable on account of its excessive grades and was abandoned as soon as the Park work was systematically taken up.

The next road was located by Captain Kingman through the pass, where the waters of Glen Creek flow from the plateau above to the valley of the Gardiner. This pass was lower than Snow Pass and more in the direct line of the road. The Golden Gate Canyon, which constitutes the pass, was exceedingly difficult to build through and took so large a part of the funds available that only a small amount could be used on the 3 miles between Golden Gate and Mammoth Hot Springs.

The direct line between these two points, and the one where the best grades and most interesting scenery were to be found, lay through an excessively difficult tract of limestone rock. This singular formation, to which local usage has given the name "hoodoos," is quite unlike any other to be seen in the Park, if, indeed, its like is to be found anywhere else in the world. It has the appearance of unslacked common lime, and the action of fire on it is to reduce it to a white powder very much like the product obtained from slacking lime. The rock abounds in every conceivable variety of form and size, from the smallest chip to immense masses a hundred or more feet through. These masses have been thrown by some natural convulsion into a most confused and irregular arrangement in which all trace of the original 1900 positions is lost. The scenic effect, while extremely interesting, is of a weird and unusual character quite unlike anything else in the Park.

This formation varies in width from a quarter to a half a mile and is wholly impassable by wagons or on horseback. Even on foot it is a difficult and laborious matter to get through. To carry a road through it was too expensive a matter to be attempted with the funds which Lieutenant Kingman had at his disposal, and it was necessary to follow a line further east, near the immediate valley of Glen Creek, where the rough formation largely disappears. But in so doing it was impossible to avoid several very heavy grades, ranging from 10 to 21 feet in the hundred. These steep pitches have always been a great drawback to the road and the source of much danger to heavily loaded coaches going in either direction. It has been found impracticable to maintain the road in good condition. The action of brakes and rough locks in descending and of the horses' shoes in ascending was to dig up whatever surfacing material might be placed on the bed of natural rock, while the rain would wash this material to the bottom of the hill or the wind would blow it away. The result was that for a good portion of the time the rough rock under the roadbed would be exposed, making the road both uncomfortable and dangerous.

It has been intended for several years to change this location, but the demands for new work elsewhere and the difficulty of finding a better route have hitherto prevented it. In looking over the entire situation at the beginning of the present season it was considered that this work was quite as urgent as any other remaining to be done in the Park. It was accordingly decided to take it up at once and not undertake any other work until the balance remaining from the completion of this could be known. In the selection of a route the natural conformation of the ground over the greater part of the distance led to an easy decision. The former road passed over a considerable elevation in the vicinity of the old military post and then dropped down into a valley, losing about 50 feet of grade which had to be overcome later on. It was decided to commence the new location at the top of this rise by keeping to the side of the hill and then commence the general ascent at once. This took the road across the foot of the Hot Springs formation and by a circuitous line carried it to the top of the hill immediately in rear of the great spring. For this distance the road also serves the purpose of giving a convenient local driveway to the top of the Mammoth Hot Springs formation.

For about a mile above the top of Formation Hill the location of the road was a simple matter, as there was natural and easy grade all the way. From there on to the "Hoodoos" the choice of route was more difficult. The location was mainly on very steep slopes, requiring a great deal of heavy side cutting, and the work was costly. The position, however, is such as to give a wide and unobstructed view over the entire Gardiner Valley and to the mountains beyond.

|

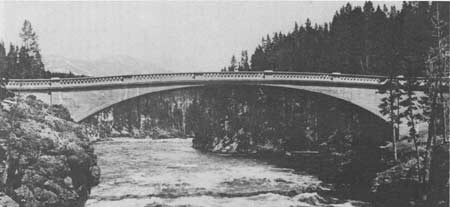

| Chittenden Bridge across the Yellowstone. (National Archives) |

The choice of routes through the "Hoodoos" was the result of a careful search over the entire belt that lay within the possible range of the road. The line finally selected gives a nearly level grade through the entire distance of 1,800 feet. The cuts and fills very nearly offset each other, and the cost of the work, though heavy, was reduced to a minimum.

Leaving this rocky tract, the road descends at a slight grade to the head of a ravine about 1,000 feet distant, and then ascends by a grade of from 3 to 7 per cent, until it joins the old road a little below Golden Gate Bridge. The introduction of a descending grade on the way up the hill was for the purpose of utilizing some work which had been done the previous year. A new location had then been selected, following pretty closely the old line, and considerable work had been done at the upper end. This location did not seem to be a sufficient improvement upon the old to justify the great cost of construction, and it was accordingly abandoned, except at the upper end, and the location of the present road was changed, from what it would have been, sufficiently to save this work. . . .

On July 5 the work of construction was commenced, and was prosecuted vigorously from that time on with three large parties. The road was opened to travel on September 10. The whole length of this new road is 16,500 feet.

The bridges in the Park have always heretofore been constructed of wood, and although they have stood exceedingly well, it was believed to be better, in replacing them as they wear out, to put in steel bridges with concrete abutments. In particular it was thought best to do this with those bridges which are nearest the railroad. The cost of transportation to the interior of the Park will probably cause timber to be used there for some time to come.

[The road from Norris to the Grand Canyon] has three of the worst and most dangerous hills on the entire system. The Virginia Cascade hill is a positive menace to the lives of travelers. Several accidents have occurred here, and one life has been lost. Stage drivers are often compelled to make passengers alight and walk down the hill. The "Devil's Elbow," a very short turn of nearly 180° is another dangerous place. Blandon Hill is a long, difficult, and dangerous ascent, which it is impossible to maintain in good condition. The long hill descending into the valley of the Yellowstone is composed of wretched material which so cuts up in wet weather as to be impossible of ascent by loaded wagons. The dense forests on top of the plateau retain the snow so late that it has to be shoveled out every spring at great expense. It is proposed to cut out some of the hills, reduce the grades on others, surface the bad stretches, and clear the timber away on the north side of the road so as to let the sun in. This work is of pressing importance, as the road will always be extensively used even after the Washburn road . . . is completed.

[The Mount Washburn Road] is the only extensive portion of the Park road system that is still untraveled. Although it will be one of the most interesting and attractive parts of all, it has never been possible in a period of over twenty-five years to get money enough to undertake it. It is a great source of disappointment to all tourists that this section of the Park is shut out to them except on horseback. That portion of the road extending from near Baronett Bridge to Mammoth Hot Springs is a part of the road leading from Gardiner to Cooke City through the Park. As is well known, Cooke City has made a long and strenuous fight to get a railroad along this line, but the Government has wisely refused this privilege. In thus refusing, however, there is something of an obligation resting on the Government to provide at least a respectable highway for travel which has to follow this route, particularly as it does not permit private parties to build roads in the Park. The road, moreover, has long been a postal route from Mammoth Hot Springs to Cooke City. This road, therefore, is required for the double reason of forming a part of the regular tourist route and providing a necessary commercial highway across the Park. The present road is one of the most difficult and dangerous to be found in all the Rocky Mountains, and it is a discredit to the Government that travel over any part of the Park has to be made at this late day over such a thoroughly wretched highway. The entire work is of immediate and pressing importance.

[A bridge over the Yellowstone near the Upper Falls] has long been of urgent importance. The public is still (twenty-seven years after creation of Park) entirely shut out from views on right bank of the Yellowstone. The superintendent has to send his patrols, for protecting the eastern part of the Park, via Baronett Bridge in extreme north of Park. The patrols at Grand Canyon and Yellowstone Lake can render no service in protecting the country on the east bank of the river. The bridge is thus a necessity both to the traveling public and for the proper police of the Park. Being in one of the grandest situations in the entire Park, its design and construction should conform to the surroundings. No cheap iron or wooden structure should be considered. It is proposed to adopt the construction known as the Melan arch, a combined steel and concrete structure in which great strength, artistic design, and reasonable cost can be combined.

1901

The condition of the old wooden bridge at [Golden Gate Canyon] had become such as to excite general uneasiness and concern among the traveling public, and although still safe it was felt that its reconstruction could not long be deferred anyway and might as well be taken up at once. After a thorough study of the site it was decided that a concrete structure would be better adapted to the situation than any other. It could be undertaken without previous accurate measurements, which would be very difficult to make while the old bridge was in place. If steel were used these measurements would have to be determined before the material could be ordered and would so delay the work that it could not be done during the season. With concrete this made no difference, for whether the foundation went a little lower or not so low as estimated the material was of a character that would adapt itself to any irregularities or variations. The site was therefore surveyed without stripping the foundation and the necessary cement for the work ordered. The rock and sand were found near the site.

It was decided to build the new viaduct in a series of arches.

The execution of the work was of extraordinary difficulty. There was an almost constant gale of wind through the canyon, which was frequently of such force as to compel a suspension of work. During the period of concrete mixing this was a most troublesome matter, and it was found necessary to commence work each day about daylight and suspend about 11 a.m. The site of the work was very contracted, and operations were seriously hampered for lack of room to work. It was, moreover, a dangerous situation, being on the face of the cliff, where any misstep would cause a fall of from 20 to 75 feet.

The necessity of interrupting tourist traffic as little as possible made great haste necessary in the execution of the work. During the time of actual construction a temporary road was provided via Snow Pass. This road was about 1-1/2 miles longer than the regular route and had some steep grades, but nothing unsafe. The greatest drawback was the excessive dust. There was scarcely a drop of rain from the time it was opened until traffic returned to the regular road and the newly moved earth cut up into a fine powder from 6 to 12 inches deep. . . .

The old bridge was closed to traffic on the 6th of August, and was reopened just four weeks later. After the resumption of traffic, work continued on the viaduct and through the canyon, and was not completed until nearly the end of October. One interesting feature of this later work was the removal of the large rock which stood at the entrance to the old bridge and partially blocked the roadway which passed between it and the cliff. The changes involved in the new structure necessitated the removal of this rock. As it was the unanimous desire of those familiar with the park that this unique and picturesque feature be retained, the rock was broken off, lifted about 6 feet to the new grade, moved out about 6 feet and down the road about the same distance, where it was set up on a new foundation, consisting of a square column of concrete 3 by 3 feet and 24 feet high. The whole foundation was then covered up, so as to remove all evidence of its artificial character. This rock weighed about 23 tons, and as its removal took place on the steep face of an unstable cliff it had to be managed with great care. . . .

In connection with the reconstruction of the viaduct it was planned to rebuild the entire road through the canyon a distance of 2,000 feet. The grades were reduced from 15 and 18 per cent to 8 per cent, and the roadway widened from a single carriage width so that teams can everywhere pass each other with ease and safety. About two-thirds of this work was done in the season of 1900.

|

| The Golden Gate Viaduct, built in 1900 by the Army Engineers. (National Archives) |

Work on this road [the East Road] was begun immediately after the 1st of July and was continued until near the end of October. . . .

A great deal of care was taken in determining the best route across the Absaroka range, which extends along the east boundary of the Park. There are only two practicable crossings, Jones Pass and Sylvan Pass, and both of these are excessively difficult. Sylvan Pass in nearly 1,000 feet lower than the other, and this fact alone made it very desirable to utilize it if possible to do so. But the physical obstacles were very great, and it was only after repeated reconnaissances that it was decided to undertake it. The pass is one of great scenic beauty and will be an important addition to the attractions of the Park.

This governing point of the road being settled, the rest of the location followed as a matter of instrumental survey mainly, for the two termini were fixed by law — one at the outlet of the Yellowstone Lake and the other where [the Shoshone River] crosses the east boundary of the reserve. The crossing of the Yellowstone River is about one-fourth of a mile below the lake and connects with the belt line about 1,000 feet distant and 1-1/2 miles from the Lake Hotel. The road then passes by a straight line over almost level ground and through a dense forest to the valley of the Pelican Creek. This valley is a swamp about one-half mile wide and is crossed by an embankment 4 feet high above the level of the swamp. Both the Yellowstone River and Pelican Creek are crossed by pile bridges. From Pelican Creek the road passes along the north shore of Indian Pond, the west shore of Turbid Lake, and crosses a low pass east of Lake Butte between the waters of Bear and Cub creeks. It crosses the latter stream above the hot springs located in its valley and then skirts the southwestern declivity of the hills that separate the valley of Cub and Clear creeks. On both sides of Cub Creek the road is led along sidehill slopes that afford fine views of the Yellowstone Lake.

The road ascends the valley of Clear Creek on the north side to its source in Sylvan Pass. This place is one of scenic attractions unsurpassed in any part of the mountains. Sylvan Lake is a small but exceedingly beautiful sheet of water near the summit of the pass, which is about 2 miles farther east. Between this lake and the pass there is a small but deep pond fed by the melting snows that drift into the valley. The bed of this lake is so porous from its composition of broken rock that the water falls upward of 15 feet in a dry season below the overflow level of spring.

From this pond east to a large spring presently to be referred to, a distance of about 1 mile, is the pass proper. It lies between high dominating peaks, which rise directly on both sides of the pass to elevations above it varying from 1,000 to 2,000 feet, the pass itself being about 8,600 feet above the level of the sea and 900 feet above the level of the Yellowstone Lake. The two most prominent peaks on the north are Avalanche and Hoyt peaks, and on the south Grizzly and Top Notch peaks. Although the summits of these peaks are about 2 miles apart, the gorge between them which constitutes the pass is very narrow. It is unique among mountain passes in that it is almost entirely occupied with broken rock, which has apparently been loosened from the cliffs on either side by the action of frost. This broken rock varies in size from pebbles to pieces a cubic yard in volume.

The descent from the pass on the east to the valley of the North Fork of Middle Creek is excessively steep, and it will be a matter of great difficulty to carry the road down with a grade even as small as 10 per cent. Just at the foot of this descent and within a short distance of the North Fork of Middle Creek is a very large cold-water spring from which a strong, clear stream flows. From this spring the road follows the valley of the North Fork to its junction with the main stream, a distance of nearly 4 miles. This is the most difficult portion of the entire route, for the slopes are excessively steep, the ground in many places unstable, the mountain sides subject to avalanches and landslides, and the ground everywhere filled with huge bowlders which have been washed down in past ages. The exact location over this distance has not yet been determined. From the junction of the North Fork with the main stream of Middle Creek the road will probably follow the north bank to its junction with Shoshone River, a distance of about 7 miles. The work along this part of the route, though much easier than along the North Fork, will still be very difficult.

From the junction of Middle Creek with the Shoshone the road will follow the latter stream, most of the way on the north bank. With the exception of the river crossings, the work over this distance will be much lighter than on any other portion of the route. The scenery along the entire valley of this stream is on the highest scale of grandeur and sublimity. The work on the east road has been costly, owing to heavy grading at the crossings of the Yellowstone and Pelican valleys and the delay caused by the necessity of transporting supplies by water over a portion of the distance. Two weeks' time was practically lost by having to use the force to fight forest fires.

1902

In the vicinity of Yanceys a road has been constructed from the north end of Crescent Hill Canyon to a little beyond the proposed crossing of the Yellowstone River, half a mile above the old Baronet Bridge. This work was nearly all on what is known as the Yancey Hill, one of the most difficult hills by the old road in the entire West. The length of the road is about 6-1/2 miles, and the difference of elevation between the river and the top of the hill, where the work began, is 1,571 feet. The old road had gradients as high as 30 per cent. On the new road the ruling gradient is 8 per cent, with one short stretch where a 10 per cent gradient could not be avoided except at very great cost.

The work on this line was of a heavy character nearly all the way. There was a large amount of dense and heavy clearing, and rock was encountered in many places along the cut banks. It was impossible to give the roadway its full final width with the means available, but it is opened to travel and can be widened very rapidly when it finally comes into use as a part of the main tourist route.

The approach to the proposed bridge over the Yellowstone on the left bank is by means of a high embankment on the right bank through a deep cut. Both pieces of work were heavy and expensive, as were also the grades leading up from the approaches to the plateau on either side. The tubular piers for Yellowstone and Lamar bridges have been purchased and hauled to the site of the Yellowstone bridge. A false work was built over the Yellowstone for the erection of the bridge, and this is now used as a temporary bridge, so that the entire stretch of road built is in use for travel in that direction. The bridges themselves have not been built, owing to the failure of the mills to furnish the material.

Work at Mammoth Hot Springs — The necessity for this work arose after the season's operations began. For several years it has been contemplated to realign the roads at Mammoth Hot Springs; cut down the steep grade near the old post; resurface all the roads in that vicinity and confine travel to them, instead of permitting it on every part of the plateau; provide water for irrigating the grounds, so as to convert the formation dust into lawn; and otherwise to improve this point, which is the administrative and business headquarters of the park. The occurrence of two consecutive low-water years in the park had reduced the water supply at Mammoth Hot Springs, so that some action had to be taken to reinforce it. The plan recommended was to bring the water of Glen Creek to the Springs, store it in a reservoir just above the old post, and carry it in mains from the reservoir to points of consumption.

1903

The situation at Mammoth Hot Springs has for many years been one of great inconvenience and discomfort on account of the character of the soil. This consisted entirely of deposit from the Hot Springs, largely carbonate of lime. In its natural state it did not sustain vegetation, and it was so soft that it ground up into a fine dust under travel, which was blown about in every direction by the winds. It has long been desired to have this ground irrigated, covered with soil, and turned into lawn, but the necessary work was so great that the means of accomplishing it have never before been available. Under the present appropriation and through the assistance of the Quartermaster's Department of the Army in its improvement of Fort Yellowstone, which is situated upon these grounds, the work was undertaken and is now practically completed. It is embraced under the following headings: Roads and walks, grading and clearing of grounds, water supply and irrigation system, buildings, electric light and power plant.

The roads around the plateau have been so laid out as to serve as well as possible the convenience of all parties concerned. They have been given a width of 20 feet, have been laid out to true grades, and surfaced to a depth of 6 to 10 inches with gravel from Capitol Hill. This gravel packs in time to a very substantial roadbed, but requires liberal sprinkling to keep down the dust. The length of roadway constructed is 9,600 feet.

From its geographic situation and the fact that Mammoth Hot Springs has become the business and administrative headquarters of the Park, and the further fact that this is the only point at which railroads can approach any of the prominent natural features or large hotels of the Park, the northern entrance is the most important of any, and this importance it will probably always retain. It has been thought fitting, therefore, to provide some suitable entrance gate at this point. This was more important because the natural features of the country at this portion of the boundary are about the least interesting of any part of the Park, and the first impression of visitors upon entering the Park was very unfavorable. During the past year the Northern Pacific Railroad has extended the Park branch of its system from Cinnabar to the boundary line at Gardiner, and the time seemed particularly favorable to combine a proper entrance gate with the new station which the railroad was about to put in at the boundary. With this purpose in view, the railroad and the Government have cooperated, and the present arrangement, now practically completed, is the result. The railroad terminates in a large loop which is tangent to the Park boundary. The wagon road also terminates in a loop which is tangent to the boundary at the same point. Between these two loops is located the railroad station, with a platform on each side — one for unloading from the cars and the other for the convenience of carriages. Within the driveway loop an excavation has been made for an artificial body of water, and provision has been made for the irrigation of the grounds around it. The water supply comes from the Gardiner River, a distance of about a mile.

Crossing the neck of the driveway loop, and on the crest of a ridge about 30 feet above the level of the station grounds, a masonry arch has been constructed of columnar basalt found in the vicinity. The width of the opening is 20 feet, the height is 30 feet, and the maximum height of the structure 50 feet. Two wing walls, 12 feet high, run out laterally from the arch to a distance of 50 feet from the center, where they terminate in small towers which rise about 3 feet above the wall. From these towers and parallel to the two branches of the loop, walls 8 feet high extend to the Park boundary. Three tablets in concrete are built into the outer face of the arch, with the following inscriptions: Above the keystone, "For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People;" on the left of the opening, "Yellowstone National Park," and on the right, "Created by Act of Congress, March 1, 1872." The corner stone of the arch was laid under Masonic auspices by President Roosevelt, on the 24th day of April, 1903. Leading from the arch across the plain, in the vicinity of the town of Gardiner, the road extends in a straight line until it strikes the Gardiner River, where a bluff crowds the road and stream together. Lines of trees have been planted along this avenue, and they are supplied with irrigation water from the ditch already referred to. The whole effect will be to give a dignified and pleasing entrance to the Park at the point where the great majority of visitors enter it.

1904

Work on the lava arch [the Gardiner Entrance] was completed, and it was thrown open to travel September 1, 1903. The small park within the terminal loop of the Government road was fenced to protect it from cattle. The trees planted along the new road across the Gardiner flat were protected against the large game that frequent the flat in the winter. With the opening of spring the snow water from the hills came down in such volume as to wash a great deal of silt into the small pond in the entrance gate park, and it was necessary to dredge it out and to take measures to cut off the surface flow, either from rain or snow, from the lake.

Particular care was taken to put the park into as good shape as the very arid region in which it exists would permit. It was sown to grass and planted with shrubbery in several places and provided with water for irrigation. These measures have been successful.

An extensive amount of work was done . . . [in the vicinity of the Grand Canyon] during the past year in connection with the erection of the new Melan arch bridge over the Yellowstone and the new steel arch bridge over Cascade Creek — both large and costly bridges. The first was built to give access to the right bank of the Grand Canyon, and a road has been constructed from the bridge to Artist Point, a view point which corresponds to Inspiration Point on the opposite side of the canyon. It is on this side of the river also that is found the only practicable way down to the bottom of the canyon.

The new bridge over Cascade Creek eliminated two bad hills and sections of road where sliding clay slopes made it extremely difficult to maintain a road. The junction of the Norris and Lake roads was changed to conform to the new road over Cascade Creek, and the entire situation at this important point placed in permanent shape.

Work was carried on on . . . [the Mount Washburn Road] with much difficulty. The snow was late leaving the mountain, and when the parties were sent to work, there was still much snow and the ground was so soaked with water as to delay work very seriously. Not as much was accomplished as had been hoped. On the canyon side a passable wagon road was opened to a mile beyond Dunraven Pass and 2-1/2 miles from the summit, and on the north side to within about 4 miles of the summit. The work is very difficult, owing to great proportion of rock work, the high altitude, and the lack of good camping places.

On the portion of this road leading from Tower Falls to Mammoth Hot Springs a half mile of new road was built to eliminate a dangerous portion of the old road near Ox Bow Creek, and the road through Crest Hill Canyon was widened to full width.

The largest and most important bridges on the entire road system were erected during the past year. They were:

The steel-concrete bridge over the Yellowstone at the head of the rapids above the Upper Falls. . . . The opening of the present season found it in almost perfect shape, having gone through a heavy winter just after its completion with no apparent damage. In consideration of the great difficulty and cost of the work, owing to its remote location and of its prominence in the eye of all visitors to this region, the owners of the Melan arch patents generously waived all royalty on this work.

The Cascade Creek bridge near the Grand Canyon is a steel arch of 120 feet span, with a 3-panel approach on each end, making a total length of bridge of 223 feet. The floor of the bridge is about 80 feet above the bed of the stream and, as already stated, eliminates two bad hills from the road system at this point.

The middle Gardiner bridge is the largest in the Park. It consists of 5 steel-arch spans, 76 feet each, and 2 approaches of 15 feet, making a total length of 410 feet. The floor is about 70 feet above the river surface. The bridge eliminates nearly 2,000 feet of road and 60 feet rise and fall at this crossing of the river as compared with the old road.

The new Baronett bridge, a steel deck truss 130 feet span, was built over the Yellowstone about half a mile above the old bridge. Upon its completion the old Baronett bridge was destroyed.

[The mileage of the park system] was given in the Annual Report of 1902 as 417 miles, consisting of 190 miles of approaches, 153 miles belt line or general circuit, and 74 miles side roads. Of the approaches, 111 miles lie outside the park, in the forest reserve. Since the above date 12 miles of road around the lake shore (side road) have been abandoned. The extent to which the roads in the forest reserve should be considered a part of the park road system is a question that has never been passed upon, but it is believed to be better to limit such mileage to those roads actually built under park appropriations. With this view there should be omitted from the above estimate the Fort Washakie military road and the road through Jackson Hole. This would reduce the mileage outside the park to 57 miles and would make the mileage of the park road system as follows:

| Approaches: | Miles |

| In the park | 79 |

| Outside park | 57 |

| 136 | |

| Beltline | 153 |

| Side roads | 62 |

| Total | 51 |

| Portion wholly within park | 294 |

[Work on the Mount Washburn Road] has been of a very heavy character, particularly on Mount Washburn and at Tower Falls. There is now a good road all the way, but over the mountain it is only single width, and the stage companies will probably not wish to use it until further enlarged. As it rests on the precipitous sides of the mountain it is important to expend considerably more money to increase its width and erect guard walls at all dangerous places. This will be by far the finest road for scenery in the park, and it is urgently recommended that it be not left in an incomplete condition.

1905

The road from Norris to the Grand Canyon, which is the most unsatisfactory location in the park, never having been laid out on any rational system, was largely improved by cutting down the hills and filling the hollows, widening and surfacing and otherwise compensating as far as possible for the defects of the original location. In particular, the road down the high hill at the Grand Canyon was relocated so as to give an easy gradient. This stretch of road lies entirely in heavy clay deposits and is exceedingly hard to maintain during the periods of wet weather. It was heavily paved with broken rock which was covered with gravel, and it is believed that it will stand in good shape. . . .

The road from Thumb Station to Lake Outlet, by way of Natural Bridge, was completed by grading to full width and surfacing with the best material available. Along the lake shore at the Thumb the alignment was in many places corrected so as to shorten the distance and even up the gradients.

The road across the summit of Mount Washburn was completed, including both the low line through Dunraven Pass and the high line passing over the summit of the mountain. This road has been one of great difficulty of construction, not only because of the general presence of solid rock in all portions, but particularly because of the shortness of season and the very wet condition of the ground until late in the summer. The road over the summit has been made 18 to 20 feet wide, instead of 12 feet as contemplated in the original estimate. This road, it is fully believed, will meet all the expectations of those who have favored its construction and will form one of the finest attractions in the tour of the park.

From Tower Falls to Mammoth Hot Springs the road has been entirely opened and completed as a permanent part of the system, thus completing the belt line or general circuit.

Much work was done on the Cooke City road from Yellowstone River to the northeast boundary of the park. An entirely new alignment was made from the Yellowstone River to near Soda Butte, the road crossing the Lamar River near the mouth of Slough Creek, instead of near the mouth of Soda Butte Creek as formerly.

The road from the Grand Canyon to Inspiration Point, which serves to give a fine view of the Grand Canyon, has been largely widened and otherwise improved.

The road opened early last season from the steel-concrete bridge over the Yellowstone to Artist Point has been fully widened and completed.

On the East road a large amount of work has been done from Sylvan Pass, 12 miles east, where it was too narrow for safe travel.

The work which was undertaken under the continuing appropriation four years ago has been practically completed, and there has also been done considerable work not contemplated in the original estimates. All the roads which it has ever been proposed to build are now open to travel. . . . Only a few minor changes of location in some of the older roads remain to be made, and the eastern and southern approaches will not require general enlargement until railway facilities in those directions are materially advanced beyond their present condition. The sprinkling system has been developed to the full extent contemplated, and has largely mitigated the dust annoyance on the main circuit. There are but few portions of the roads that can not now be traveled with speed, safety, and comfort equal to what it was hoped to obtain with the funds granted by Congress.

New roads — It has been the policy of the officer in charge of the improvement work, and also of the present superintendent of the park, to discourage any material extension of the park road system. There are now roads enough. There are four excellent approaches, one on each side of the park, along routes fixed by nature in the valleys of important streams, and these will serve any probable future public needs. It is impossible that any important railroad system should build to the border of the park in a way that it could not be served better by existing approaches than it could by any others that might be built.

From Hiram Chittenden, Reports on "Improvements of the Yellowstone National Park." ARCE, 1893 and 1899 to 1905 (incl).

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Nov 15 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

baldwin/chap7a.htm

Top

Top