|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Secret of the Big Trees |

|

Manifestly it was necessary to devise some new line of research which should not only furnish dates, but should prove positively the existence or nonexistence of changes of climate, and should do it in such a way that the investigator's private opinions, his personal equation, so to speak, should not be able to affect his results. The necessary method was most opportunely suggested by an article published in the Monthly Weather Review in 1909 by Prof. A. E. Douglass, of the University of Arizona. In regions having a strongly marked difference between summer and winter it is well known that trees habitually lay on a ring of wood each year. The wood that grows in the earlier part of the season is formed rapidly and is soft in texture, while that which grows later is formed slowly and is correspondingly hard. Hence each annual ring consists of a layer of soft, pulpy wood surrounded by a thinner layer of harder wood which is generally of a darker color. Except under rare conditions only one ring is formed each year, and where there are two rings by reason of a double period of growth, due to a drought in May or June followed by wet weather, it is usually easy to detect the fact. In the drier parts of the temperate zone, especially in regions like Arizona and California, by far the most important factor in determining the amount of growth is the rainfall. Prof. Douglass measured some 20 trees averaging about 300 years old. He found that their rate of growth during the period since records of rainfall have been kept varies in harmony with the amount of precipitation. Other investigators have since done similar work elsewhere, and it is now established that in regions with cold winters and dry summers the thickness of the annual layers of growth gives an approximate measure of the amount of rain and snow.

|

|

CROSS SECTION OF A

SEQUOIA SHOWING THE GROWTH RINGS.

|

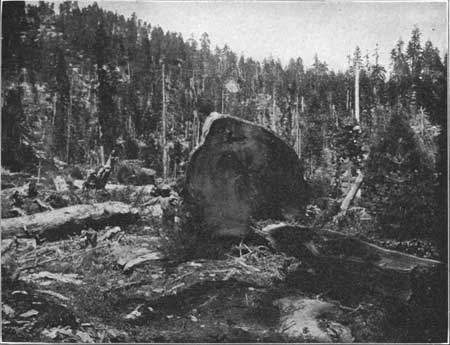

Obviously the best trees upon which to test the theory of climatic changes are the big trees of California. They grow at an altitude of 6,000 or 7,000 feet on the western slope of the Sierra Nevadas. Abundant snow falls in winter and there is a fair amount of rain up to about the 1st of June, but the rest of the warm season until the end of September is dry. Hence the conditions are highly favorable to the formation of distinct, easily-measured rings. The size of the trees makes the rings fairly thick, and hence easy to see. The only difficulty is that the number of trees which have been cut is small. The region where they grow is relatively inaccessible, the huge trunks are very difficult to handle, and the wood is so soft that its uses are limited to a few purposes for which great durability is required. Hence several years may pass without the cutting of more than a few scattering trees. The resistance of the wood to decay is so extraordinary, however, that stumps 30 years old are almost as fresh as when cut, and their rings can easily be counted. As climatic records they are as useful as trees that were cut the present year, if only one can ascertain the date when they were felled.

|

|

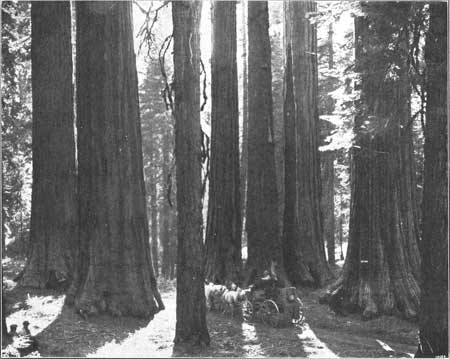

MARIPOSA GROVE,

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK.

Photograph by Pillsbury Picture Co. |

Toward the end of May, 1911, I left the train at Sanger, near Fresno, in the great inner valley of California, and with two assistants drove up into the mountains through the General Grant National Park to a tract belonging to the Hume-Bennett Lumber Co. There we camped for two weeks, and then went to a similar region, some 60 miles farther south on the Tulare River, east of Portersville. Few parts of the world are more delightful than the Sierras in the early summer. In the course of our work we often tramped through valleys filled with the straight, graceful cones of young sequoias overtopped by the great columns of their sires. Little brooks or rushing streams full of waterfalls flowed in every depression, and a drink could be had whenever one wished. On the sides of the valleys, where the soil is thin and dry, no young sequoias could be seen, although there were frequent old ones, a fact which suggests that conditions are now drier than in the past. Other trees, less exacting in their demands for water, abound in both their young and old stages, and one climbs upward through an array of feathery pines, broad-leaved cedars with red bark, and gentle firs so slender that they seem like veritable needles when compared with the stout sequoias.

|

|

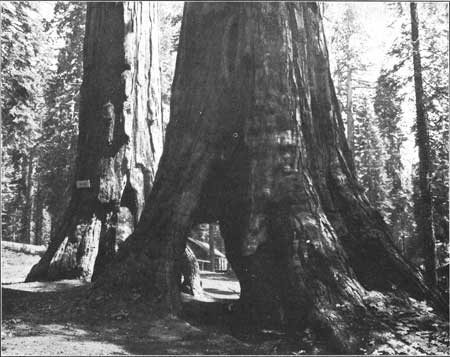

MARIPOSA GROVE,

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK.

Photograph by Pillsbury Picture Co. |

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

huntington/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 12-Feb-2007