|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Secret of the Big Trees |

|

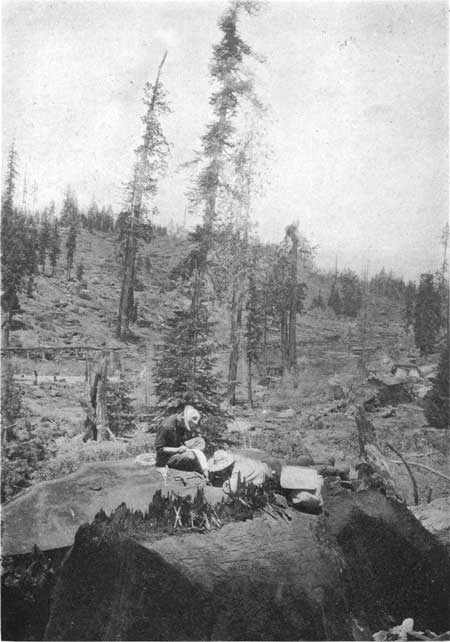

We tramped each day to our chosen stumps, sometimes following old chutes made by the lumbermen to guide the logs down to the valleys, and sometimes struggling through the bushes, or wandering among uncut portions of the primeval forests. Often there was frost on the ground during the first week or two, and the last rains of the spring made the ground oozy, while the flat tops of the stumps smoked in the summer sun as soon as the clouds disappeared. Our method of work was simple. As soon as we reached a place where sequoias had been cut, we began prospecting for large stumps. The method of cutting the trees facilitated our work by furnishing a smooth sawed surface. Before the lumbermen attack one of the giants they build a platform about it 6 feet or more above the ground and high enough to be clear of the flaring base of the trunk. On this two men stand and chop out huge chips, sometimes a foot and a half long. As the cutting proceeds a great notch is formed, flat on the bottom and high enough so that the men actually stand within it. In this way they chop 10 feet more or less into the tree, until they approach the center. Then they take a band saw 15 or 20 feet long and go around to the other side. For the next few days they pull the great saw back and forth, soaking it liberally in grease to make it slip easily, and driving wedges in behind it in order to prevent the weight of the tree from resting on the saw. Finally, when the tree is almost cut through, more wedging is done, and the helpless trunk topples over with a thud and a stupendous cracking of branches that can be heard a mile. The sawn surface exposes the rings of growth so that all one has to do is to measure them, provided the cutting has taken place recently. In the case of older stumps we sometimes were obliged to scrape the surface to get rid of the pitchy sap which had accumulated on it. In other cases, especially where the stumps had been burned, we had to chisel grooves or take a whisk-broom and sweep off an accumulation of needles and dirt.

|

|

MEASURING THE ANNUAL

RINGS.

|

When all was ready, two of us lay down on our stomachs on the top of the stump, or it might be on two stumps standing close together, while the third sought the shade, or the sun, or a shelter from the rain, as the weather might dictate. The two who were on the stump were equipped with penknife, ruler, and hand lens. The ruler was placed on the fiat surface of the stump with its zero at the edge of the outer ring. Then we counted off the rings in groups of 10, read the ruler and called off the number to the one who sat under shelter with notebook and pencil. Had the lumbermen seen us we should have appeared like crazy creatures as we lay by the hour in the sun and rain calling out "forty-two," and being answered by the recorder, "forty-two": "sixty-four," "sixty-four": "seventy-eight," "seventy-eight," and so on, interminably. It was not inspiring work merely to measure, and it was distinctly uncomfortable to lie on one's stomach for hours after a hearty meal. Often it was hard to see the rings without a lens, and in some cases even the lens scarcely showed them all, for the smallest were only two-hundredths of an inch thick, very different from some of the big ones, half an inch thick. Nevertheless, the work was decidedly interesting. If we were busy on different radii of the same tree there was always a rivalry as to who would finish first but undue haste was tempered by the danger that the results of our two measurements might not agree. The chief interest therefore lay in seeing how nearly the same number of rings would be counted on different radii. If we were at work on different trees the rivalry was as to whose tree would turn out oldest; for, like the rest of mankind, we had a feeling of personal merit if the thing with which we by pure chance were concerned happened to turn out better than that of our neighbor.

One of our chief difficulties lay in the fact that in bad seasons one side of a tree often fails to lay on any wood, especially in cases where a clump of trees grow together in the sequoias' usual habit, and the inner portions do not have a fair chance. Often we found a difference of 20 or 30 years in radii at right angles to one another; and in one extreme case, one side of a tree 3,000 years old was 500 years older than the other, according to our count. All these things necessitated constant care in order that our results might be correct. Another trial lay in the fact that in spite of the extraordinary durability of the wood, a certain number of decayed places are found, especially at the centers of the older trees, exactly the places which one most desires to see preserved. Even these decayed places, however, added their own small quota of interest. Looking down into the damp, decayed holes, we frequently saw the heads of greenish frogs, which slowly retreated if we became inquisitive and poked them. At other times, in drier places, lizards of a smooth, unpleasant complexion of brownish gray wriggled hastily into cavities in the rotten wood. Once I pulled off a large decayed slab from the side of a stump, and started back in surprise when two creatures with yellowish-brown bodies and black wings flew out. I was about to look for a bird's nest when one of my companions called out " Bats."

|

|

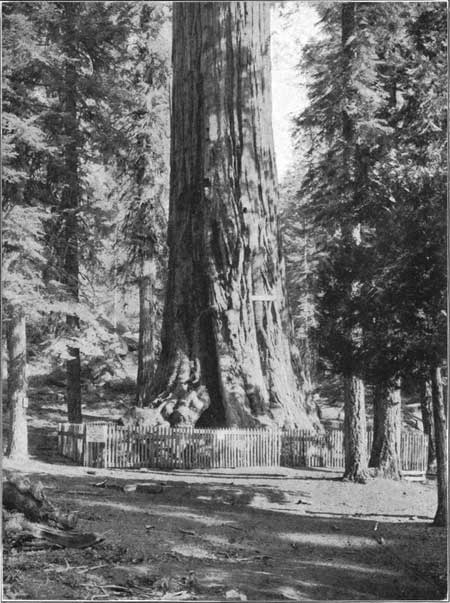

GENERAL GRANT TREE,

GENERAL GRANT NATIONAL PARK.

Height, 264 feet; diameter, 35 feet. The General Grant Grove, in the park of the same name, has an area of 235 acres and contains 190 trees exceeding 10 feet in diameter. |

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

huntington/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 12-Feb-2007