|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

The Secret of the Big Trees |

|

The frogs, lizards, and bats did not trouble us, and, fortunately, we were free from mosquitoes. There was one creature, however, which sometimes seriously interfered with our work. As we lay on our stomachs, our left fists resting on the black surface of a stump to prop our unshaven chins, and our right hands rapidly touching ring after ring with a penknife as we counted our decades—as we lay thus, with eyes closely focused at a distance of about 8 inches, frightful forms came rushing into the field of vision. They were black and horny, with powerful nippers on their heads, and with white hairs on their abdomens, giving them a moldy look. They seemed nearly as large as mice, and their speed of movement was positively alarming. With open nippers they rushed at our rulers and knives and tried them to see if they were edible. Sometimes they even nippd our hands, and more than once one of us uttered a sharp exclamation and jumped so as to throw knife and ruler to the winds and cause the waste of 10 or 15 minutes in finding the place again. When we brushed the creatures away and looked at them from the normal distance they proved to be nothing but large black ants, about half an inch long. More pertinacious insects I never saw. Again and again I brushed an ant away to a distance of 6 or 8 feet, and watched that same ant turn the moment it alighted and rush back to the attack, and it did this not once but five or six times.

|

|

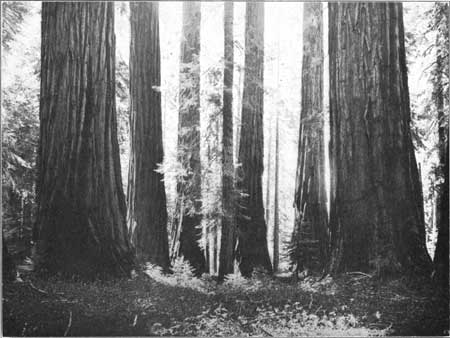

NEAR CAMP SIERRA,

SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK.

|

During the 12 weeks that we were in the mountains in the two seasons of 1911 and 1912 we succeeded in measuring over 450 trees, 79 of which were 2,000 or more years of age. The others were of various ages down to 250 years, for we measured a considerable number of relatively young trees for purposes of comparison. The process of constructing the climatic curve from the data thus obtained is less simple than might at first appear. The obvious method is to ascertain the average growth of all the trees for each decade, from the earliest, times to the present, and then to draw a curve showing how the rate has varied. The high places on such a curve will indicate times of comparative moisture, while the low places will indicate aridity. This method is too simple, however, for it takes no account of the fact that all trees grow faster in youth than in old age. Each species has its own characteristic curve of growth, as it is called. For example, during the first 10 years of its life the average Sequoia washingtoniana grows about an inch in radius, that is, it reaches a diameter of 2 inches; at the age of 200 years the average tree adds about nine-tenths of an inch to its radius each decade; at the age of 500 years about six-tenths of an inch; and at the age of 1,700 only three-tenths. These figures have nothing to do with the rainfall, but indicate how fast the tree might be expected to grow if they were subject at all times to the average climatic conditions, without any variations from year to year.

|

|

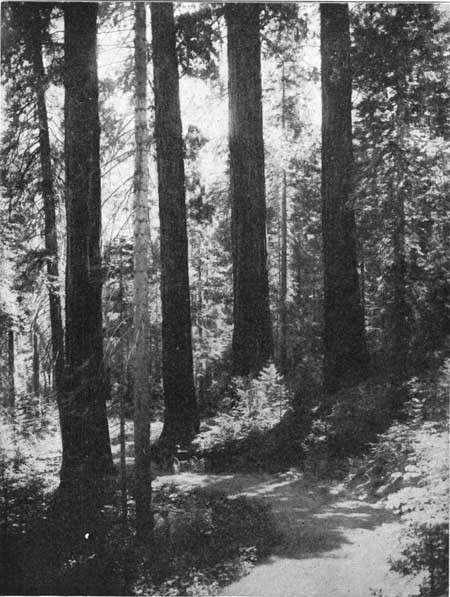

SEQUOIAS ON GIANT

FOREST ROAD, SEQUOIA NATIONAL PARK.

The Giant Forest has an area of 3,200 acres and contains 500,000 trees, of which 5,000 exceed 10 feet in diameter. There are 11 other groves in the Sequoia National Park ranging from 10 to 2,000 acres in area and containing from 6 to 3,000 trees exceeding 10 feet in diameter. |

Evidently, if we desire to institute a fair comparison between the growth of a tree 200 years old and of one 1,700 years old, we must either multiply or divide by 3. By applying such corrections to each measurement among the 105,000 which made up the work of our two summers, we are able to eliminate the effect of differences in the ages of the trees. The process is purely mathematical and depends in no respect upon the individual ideas of the computer. In addition to the correction for age, there is another, which I have called the correction for longevity. What sort of tree is likely to have a long life? Is it a vigorous, well-grown tree, the kind that one would pick out as especially flourishing in its youth? Not at all. The tree which is likely to live to a ripe old age of two or three thousand years grows slowly in its early days. Its actual rate of growth may be only half or two-thirds as great as that of the trees which attain an age of 500 or 1,000 years. Hence, in order to institute a fair comparison between the rate of growth in the days of Darius and now it is necessary to make still further corrections. This process, like the other, is purely mathematical. The only difficulty is that in order to secure high accuracy a large number of trees of all ages is necessary. It is easy to obtain plenty of young trees under 2,000 years of age, but older ones are so scarce that we have not obtained enough to render the corrections fully exact. Hence in the earlier parts of the curve, the details are less exact than could be desired, and the fluctuations are relatively too great, since they are not smoothed out by the use of a large number of trees. In the portion of the curve since about 100 B. C., however, the fluctuations for minor periods and also for centuries show no appreciable errors except such as are due to special accidents. Nevertheless there is some doubt as to whether the curve as a whole in its descent from early times down to the present should slope more or less than is here shown.

| <<< Previous | Next >>> |

huntington/sec5.htm

Last Updated: 12-Feb-2007