|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 5 The Wolves of Mount McKinley |

|

CHAPTER ONE:

INTRODUCTION

Outline of the Study

IN 1939 I WAS REQUESTED to make a study of the relationships between the timber wolf (Canis lupus pambasileus) and the Dall sheep (Ovis dalli dalli) in Mount McKinley National Park, Alaska. I arrived in the park on April 14, and 3 days later was taken 22 miles into the park by dog team and left at a cabin on Sanctuary River where I started my field work. The next morning I climbed a mountain and saw a ewe and yearling on a grass slope, the first white sheep I had seen for 16 years, and a little later, through the field glasses, I "picked up" a beautiful ram resting on a ledge, the graceful curved horns silhouetted against a spring-blue sky. A strong cold wind was blowing on top so I slipped on my parka. During the day 66 sheep were classified, 20 of which were yearlings. Wolf tracks were seen and a wolf dropping, containing sheep hair, was found. The long, slow process of gathering data had begun.

In order to avoid accumulating only a number of miscellaneous observations I directed my efforts along the most promising lines and kept in mind the main points on which it was desirable to get quantitative data.

First it was necessary to learn what the wolves were eating. Killing the wolf to examine the stomach contents, in this case, was too much like killing the goose that laid the golden eggs. A dropping tells almost as much, so, to learn the food habits, wolf droppings were gathered, and of course observations of the wolves in action were made whenever possible. From the analysis of many droppings, some notion of the extent of the feeding on mountain sheep was obtained. The next point to determine was to what extent the sheep eaten represented carrion. It could, of course, all have been carrion. Some of it certainly was. But if it were learned that sheep are commonly run down and killed by wolves then it would be necessary to learn what kind of sheep are killed. Were they the ailing, the aged, and the young, or were all classes being taken indiscriminately? These were points difficult to determine. A thorough search of the sheep hills yielded skulls of 829 sheep. These skulls showed in what types of animals the mortality in the population lay and brought up fundamental problems concerning the natural role of the predator.

Another obvious line of attack was to classify the white sheep population to determine the size of lamb crop and the survival of yearlings in order to learn the losses during the first year a critical period. Classifications were made in must parts of the range at every opportunity. Besides these salient points, all other available information on the wolves and sheep was gathered. The food habits and range of the sheep were of special interest, for adequate range is often an important factor in predatory problems. Historical data on the wolf and sheep populations were sought, for such data are frequently enlightening.

Involved in this same problem were other animals which required study to determine what part they play in regard to the sheep and to the wolf. The caribou is a basic food supply of the wolf in interior Alaska, so it had an important bearing on the wolf-sheep relationships. There were questions such as the extent that the caribou serve as a buffer species for the mountain sheep. The caribou were studied in much the same manner as were the sheep. It is at least a tradition that the golden eagle who shares the high country with the sheep is one of its principal enemies. Perhaps the golden eagle was levying too heavy tribute on the sheep or perhaps it was a valuable citizen. Therefore, the food habits and actions of this bird required attention. Another animal on the agenda was the grizzly bear, known to be fond of caribou and sheep meat. The wolf has been accused of being destructive to foxes, so it seemed important to make what observations I could on this point. Furthermore, since foxes are a potential enemy of the lambs, their food habits required study. The moose was present in some numbers and, since it is generally considered a source of food for wolves, some attention was also given to this species. I had hoped to make observations of the coyote in the sheep hills but it was too scarce for study. Coyotes are more plentiful adjacent to the park in the rabbit country, a fact which may in itself be significant. Other animals like the porcupine, marmot, ground squirrel. snowshoe hare, mouse, and ptarmigan have been considered in their relationships to the larger forms.

This in brief gives the scope of the study which is reported in this paper. A chapter is devoted to each of the animals which has an important bearing on the problem. Some information not bearing directly on the problem is included in these chapters in order to round out the general ecological picture. Much of the data on the wolf is discussed in chapters dealing with its prey species.

In 1939 the field work, begun in April, was continued to the end of October. In 1940 I returned to the park in April and for the next 15 months remained in the field. The field observations were thus made over a period including most of three spring and summer seasons, two autumns, and one winter. In 1922 and 1923 I had spent several months in Mount McKinley National Park on other work, so when I undertook the present assignment I was already familiar with part of the area and some of the early wildlife conditions there.

In 1940 and 1941 I worked alone, but in 1939 I was ably assisted by two enrollees of the Civilian Conservation Corps. One of the enrollees, Emmett Edwards, was especially suited for the work as he had climbed many of the major peaks in the West. Irwin Yoger helped in the field work and drove the automobile when necessary.

An automobile road, 89 miles long, leads from the railroad to a little beyond Wonder Lake. This road passes through the heart of the sheep ranges. In a relatively short time I was able to drive in summer to any point along the road and from there cover the limits of the adjoining sheep hills in a day's tramp. In order to reduce the amount of back-tracking and thus cover more territory, I often had someone drive me to a place on this road from which I would hike in a semicircle and be picked up in the evening 10 or or more miles from the the starting point.

The work necessitated a large amount of hiking and climbing. In 1939 I walked approximately 1,700 miles. The following two summers the work still required much climbing but fewer long hikes. During the winter I traveled on skis. At this season a bedroll and food were carried in most eases and relief cabins were used for shelter.

In the summers of 1939 and 1941 I camped at Igloo Cabin and in 1940 at the East Fork cabin, 34 and 44 miles, respectively, by road, west of Park Headquarters.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply indebted to a number of persons for their help and support. To Harry J. Liek, Superintendent of Mount McKinley National Park when I first arrived, and later to Supt. Frank T. Been I am grateful for many favors, such as the use of an automobile, quarters, and various kinds of equipment. In fact, the entire park staff was of great assistance. Former Chief Ranger Louis M. Corbley and Ranger John C. Rumohr supplied considerable information on early conditions and were most helpful at all times. Ranger Raymond W. McIntyre accompanied me on several winter trips. Harold R. Herning, William H. Clemons, Jess Morrison, Charles Peterson, and Andrew Fluetsch cooperated in many ways, and were out on trips with me. Former Ranger Lee Swisher made a special trip to the park to tell me of his experiences there with big game in previous years, and of his trapping north of the park more recently. I also had the use of one of his relief cabins. Trapper John Colvin furnished much information and several specimens. L. J. Palmer of the Fish and Wildlife Service spent 2 weeks with me studying vegetation. Personnel of the Alaska Road Commission employed in the park cooperated in numerous ways. Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Rust drove me to Livengood and to Eagle Summit to see captive wolves and caribou range. Prof. Otto W. Geist of the University of Alaska gave much valuable assistance. Former Warden Sam White made available various reports on the wildlife in interior Alaska. Dr. and Mrs. Aven Nelson of the University of Wyoming kindly identified much plant material. Dr. Carl P. Russell of the National Park Service and Clifford C. Presnall of the Fish and Wildlife Service strongly supported the field work at all times. I am especially indebted to Director Ira N. Gabrielson and to Dr. W. B. Bell of the Fish and Wildlife Service for furthering the field work and making arrangements for me to write this publication; to Victor H. Cahalane in direct charge of the project, for helpful cooperation from the beginning of the field work to the completion of the manuscript; and to my brother, O. J. Murie, who assisted me in many ways, and contributed the wolf sketches made from descriptions given to him.

My first expedition to Mount McKinley National Park to study wolf-sheep relationships was made in 1939 and was sponsored by the National Park Service, and the second, made in 1940-41, was supported jointly by the National Park Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Climate

The region north of the Alaska Range is colder and has less snowfall than the region south of the range which is benefited by the warm ocean current. But on the north side of the range there is considerable difference in temperature between the lowlands of the interior and the mountain region of Mount McKinley National Park. The summers in the park are definitely cooler and the winters warmer than at inland points such as Nenana and Fairbanks. Strong south winds often prevail in the park in winter. Precipitation in summer varies considerably, at least so it seems to one in the field. In 1939 for a month and a half it rained some almost every day. In 1940 the rainfall was moderate, and satisfactory weather prevailed, but in 1941 June and July were again rainy and cloudy although many clear days were reported for August. The yearly precipitation is about 15 inches. Snow in September is to be expected, and may fall in August, but usually at this time it quickly melts in the valleys and on south-facing slopes. The winter snow on the foothills has largely disappeared by the first of June, although some drifts last far into the summer.

TABLE 1 - Temperature (° F.) and precipitation (inches) at McKinley Park Station, Nenana, and Talkeetna, Alaska (Capps, 1932)

| MONTHLY MEAN TEMPERATURE | ||||||||||||||

| Station | No. of years' record | Jan- uary |

Feb- ruary | March | April | May | June | July | August | Septem- ber | Octo- ber |

Novem- ber | Decem- ber | An- nual |

| McKinley Park Nenana Talkeetna |

6 8 11 | 1.6 -5.9 8.4 | 6.4 3.0 16.7 |

13.6 8.2 21.6 | 24.0 27.6 32.9 | 42.1 50. 45.5 |

54.3 57.6 54.6 | 56.1 61.5 58.1 | 53.9 58.0 55.2 |

43.1 44.6 39.9 | 28.9 26.7 34.7 | 15.6 3.4 20.6 |

0.7 -7.9 9.7 | 28.4 27.2 33.2 |

| DAILY MEAN MINIMUM TEMPERATURE | ||||||||||||||

| McKinley Park Nenana Talkeetna |

5-6 5 8 | -7.8 -23.5 -0.8 | 4.1 -6.6 3.6 |

3.5 -2.3 10.8 | 14.3 14.3 20.5 | 30.8 34.6 31.6 |

40.4 46.6 40.9 | 44.3 51.1 45.4 | 42.1 46.6 44.0 |

33.6 35.0 35.0 | 19.7 18.3 26.7 | 6.6 -6.0 12.3 |

-6.3 -15.7 0.2 | 18.8 16.0 22.5 |

| LOWEST TEMPERATURE OF RECORD | ||||||||||||||

| McKinley Park Nenana Talkeetna |

6 6-7 11 | -52 -63 -48 | -47 -51 -33 |

-28 -50 -24 | -33 -26 -23 | 4 18 20 |

25 35 27 | 31 37 31 | 28 30 27 |

2 15 20 | -15 -17 -8 | -34 -49 -30 |

-54 -56 -41 | -54 -63 -48 |

| MONTHLY AND ANNUAL NORMAL PRECIPITATION | ||||||||||||||

| McKinley Park Nenana Talkeetna |

6 8 11 | .50 .38 1.68 | .57 .51 2.18 |

.59 1.04 1.85 | .93 .36 .91 | 1.31 .66 .95 |

2.31 1.50 1.63 | 2.25 2.63 3.84 | 1.83 1.98 4.50 |

1.80 1.58 4.80 | .92 .80 4.00 | .45 .26 1.54 |

.63 .30 1.81 | 14.09 12.00 29.69 |

| MONTHLY AND ANNUAL SNOWFALL | ||||||||||||||

| McKinley Park Nenana Talkeetna |

4-6 8 6-8 | 11.3 5.9 22.9 | 9.1 5.3 23.2 |

7.5 9.6 28.4 | 1.9 3.4 13.4 | Trace 1.2 .5 |

0 0 0 | 0 0 0 | 0 Trace 0 | 2.3 .3 2.6 |

6.5 7.7 10.3 | 7.6 4.5 15.8 | 9.2 4.0 24.6 |

55.4 41.9 141.7 |

Physiography

In the central part of the Alaska Range, extending westward some 105 miles from the Alaska Railroad, lies Mount McKinley National Park. From the crest of the range, and within the park boundaries rise several massive mountains, including Mount McKinley which is 20,300 feet in altitude. Most of the park lies on the north slope of the range, with its long axis parallel to the range. It is from 30 to 35 miles in width and contains 3,030 square miles.

In the eastern part of the park high lateral ridges run northward from the main range for distances up to 10 miles before sloping down into low rolling terrain, from which again rises a foothill range. As far westward as Sanctuary River this "outside" range is a single ridge. West of Sanctuary River this foothill range broadens out into an irregular mass of mountains that approach the main range so closely that the intervening lowland is squeezed into narrow low passes. These outside mountains have elevations from 4,000 to 6,000 feet, and rise from river beds 2,500 to 3,000 feet in altitude. Several glacial streams flow northward from the main range and have cut deep canyons through the foothills, thus creating excellent mountain sheep habitat. Westward from Mount Eielson the foothills disappear and the main Alaska Range rises abruptly from the interior Alaska lowlands.

Much of the area is sedimentary rock, but there is a considerable amount of igneous material scattered throughout (Capps, 1932). The terrain is varied, with talus slopes and rounded summits, as well as cliffs and rugged contours. Most of the streams are of glacial origin. They are swift and braided, flowing over broad gravel bars. There are numerous small ponds and lakes, suitable for waterfowl breeding places.

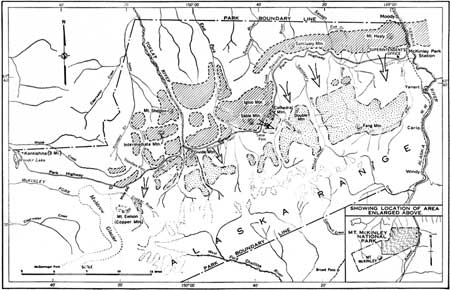

Map of the Eastern Portion of Mount McKinley

National Park. The present summer and winter ranges of Dall sheep in

Mount McKinley National Park are outlined. The obliquely lined areas

show winter range; this range is also occupied by sheep during the

summer. The stippled areas indicate summer range only. As only sheep

concentration areas are outlined, the ranges appear to be disconnected.

Actually, the ranges are continuous since sheep move readily from one

favorite locality to another and a few may be found on the less rugged

slopes outside the outlined areas. When the sheep were more abundant,

many of the lower slopes, lying between the rugged areas, were also much

used. A few sheep are present in the Windy Creek region but their range

is not indicated on the map. Arrows show the general direction of sheep

migration from various sections of the winter range to the summer

range.

Vegetation

Mount McKinley National Park lies largely above timber line, which occurs at 2,500 to 3,000 feet altitude. Narrow strips of timber extend varying distances along the river bottoms. This limited forest growth consists chiefly of white spruce (Picea canadensis), with some black spruce (Picea mariana) in wet situations. Many of the plant species found in the treeless areas also occur in various degrees and combinations among the trees. There is a scattering of cottonwoods (Populus trichocarpa), and aspen (Populus tremuloides) in suitable places. White birch (Betula papyrifera), so common in interior Alaska, is almost completely absent, being found only in the extreme eastern end of the park.

In the open lowland areas shrubs constitute a major feature of the vegetation. These shrubs consist largely of dwarf Arctic birch (Betula nana), several species of willow (Salix spp.), and blueberry (Vaccinium uliginosum). The dwarf birch and blueberries generally are knee high or less, and the willows vary from the dwarf creeping varieties to tall growths, sapling size. The taller willows are generally found along streams and draws. Alder (Alnus fruticosa) is plentiful in some areas. Much of it was found on the lower north slopes of the outside mange. Buffaloberry (Shepherdia canadensis) is abundant over many gravel beds. Other common shrubs are crowberry (Empetrum nigrum), lowbush cranberry (Vaccinium vitis-idaea minus), Labrador tea (Ledum groenlandicum), rhododendron (Rhododendron lapponicum), and Arctous alpina in the open and Arctous rubra in the woods. Most of these shrubs occur in the timber as well as in the open.

Grasses, sedges, and wood rushes are dominant in a great many lowland situations and are found through out the park. Bordering the highway and in some of the old trails Calamagrostis canadensis forms dense stands. Cotton grasses (Eriophorum spp.) are conspicuous in the wet tundra. Leaf lichens are abundant, and over wide areas of rolling lowland, species of Cladonia and Cetraria occur in varying degrees, in some places forming thick carpets. The family Leguminosae is well represented by species of Hedysarum (found abundantly on old river bars), Oxytropis, Astragalus, and Lupinus. Some of the conspicuous flowers are coltsfoot (Petasites), fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium), willow herb (E. latifolium), Pedicularis (several species), Mertensia, Polemonium, Saxifraga (a number of species) Boykinia richardsoni, poppies (Papaver), moss campion (Silene), Delphinium, and Anemone.

Perhaps the most characteristic plant on the mountain slopes is Dryas, which forms mats over vast areas and in other places is mixed with grasses and other vegetation. Species of Dryas also form mats over many old river bars. Many species of plants found in the open lowlands also occur on the ridges, but the associations on the ridges are somewhat different. The commonest grasses are species of Poa and Festuca which form low bunchy growths. Hierochloe alpina occurs widely, and sedges (Carex) and woodrushes (Luzula) are abundant; dwarf willows (Salix) of several species are common.

The vegetation on many ridges is so short and dense that it has the appearance of a well-kept lawn. On south exposures or where erosion is active, the vegetation is sometimes sparse. An herbaceous cinquefoil (Potentilla) was conspicuous on some of these south slopes. There are many talus slopes where vegetation is scant.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

fauna/5/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016