|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 5 The Wolves of Mount McKinley |

|

CHAPTER TWO:

WOLF

Physical Characteristics

I WAS A LITTLE UNCERTAIN about the identification of the first wolf I saw in Mount McKinley National Park. I was not sure whether it was a wolf or a coyote. The animal was some distance away, on a ridge parallel to the one from which I was watching, so that size was not a good criterion for identification and the color was about the same as that of a coyote. But it was noted that the legs appeared exceptionally long and prominent, and that there was something about the hind quarters which was peculiar, giving the animal just a suggestion of being crouched. On the slope it appeared more clumsy in its actions than a coyote. Its ears were more prominent than I had expected in a wolf. These characteristics were later found to be typical. The behavior of this wolf was of special interest so I checked my identification by an examination of the tracks which were approximately 5 inches long. After becoming familiar with the wolves, there generally was no difficulty in making identifications but still on a few occasions a distant gray wolf could have been mistaken for a coyote.

There are some northern sled dogs which resemble wolves closely enough so that it would be hard to identify them correctly if they were running wild. Some years ago I drove a sled dog which was so similar to a wolf that even on a leash it could be mistaken for one. However, this animal was supposed to be a quarter-breed wolf. The wolf is lankier and has longer legs than the average sled dog. His chest is narrower so that the front legs are much closer together than those of the usual broad chested sled dog.

There is much individual variation in wolves, especially in regard to color. They are usually classified as white, black, and gray, but among these types there is an infinite amount of variation. The wolves referred to as gray are sometimes a brownish color similar to that of a coyote. One type of animal is whitish except for a black mantle over the hack and neck. In some, the fur on the neck is strikingly different from the rest of the coat. Some gray wolves have a striking silver mane. The tail is tipped with black. The black wolves often have a sprinkling of rusty or yellowish guard hairs which create a grizzled effect, and many are characterized by a vertical light line just back of the shoulder. Further description of their colors is given in the discussion of a family of wolves living at East Fork (see p. 25).

The black and gray wolves were present in about equal numbers in Mount McKinley National Park. Dr. E. W. Nelson (1887), reporting on his sojourn in Alaska from 1877 to 1881, states that at the head of the Yukon River the black wolves predominated and that the gray wolves were most abundant near the Bering Sea. I do not know if there is any dominance of color in different regions of Alaska at the present time but I expect that in most regions both color types are present.

I know of few weights of Alaska wolves but judge that the adult male in good flesh generally weighs approximately 100 pounds. Estimates have been made as high as 150 pounds and more. There is much variation in size, so that exceptionally large animals could be expected. Judging from the wolves that I saw, the females are smaller than the males.

Figure 2: Tracks of front foot (at bottom) and hind foot (at top) of a wolf in soft mud. The front foot track is always noticeably broader than that of the hind foot. [East Fork River, August 26, 1940.] |

Tracks

The tracks of a wolf can easily be distinguished from those of a coyote by their large size, and the long stride, but probably would often be indistinguishable from those of the large northern sled dog.

The front foot measures larger than the hind foot, being definitely broader and usually slightly longer. The width of the track, of course, varies according to the speed at which the wolf is traveling. When the animal is running fast or galloping the foot spreads considerably.

Tracks of a pup, on August 26, when it was about 3-1/2 months old, measured as follows; Front foot, 4 inches long, 2-7/8 inches wide; hind foot, 3-1/2 inches long, 2-5/8 inches wide.

The measurements of a 4-1/2-month-old captive wolf pup (see page 45), a sister of the above wild pup, on September 24, were as follows: Front foot, 4-3/4 inches long, 3-3/4 inches wide; hind foot, 4-1/2 inches long, 3 inches wide.

The following measurements of tracks in moist mud are typical and show some of the variations. In most cases the animal had apparently been trotting.

| Foot of animal | Length | Width |

| Inches | Inches | |

| Front | 5-1/8 | 3-3/8 |

| Hind | 4-5/8 | 3 |

| Front | 4-7/8 | 13-1/2 |

| Hind | 4-3/8 | 3-1/8 |

| Front | 5-1/4 | 4-1/4 |

| Hind | 5 | 3-1/2 |

| Front | 5-1/4 | 3-3/4 |

| Hind | 4-5/8 | 3 |

1Tracks of black female. | ||

The pace of the wolf in walking and trotting on the level varies from 25 to 38 inches. In 7 inches of snow the pace measured between 27 and 30 inches. The pace of a track, in 6 inches of snow, probably made by a trotting animal, averaged 29 inches. A series of consecutive paces on a gravel bar measured 32, 34, 30, and 32 inches. In climbing a steep slope of about a 45-degree angle, in a few inches of snow, the pace of a band of wolves averaged about 16 inches. (By pace is meant the distance between the tracks of the two hind feet or the two front feet. A full stride would be twice the pace.)

In traveling through snow a band of wolves will often go single file, stepping in one set of tracks. The hind foot in such cases falls in the tracks of the front foot. At other times the hind foot may or may not fall in the track of the front foot. In order to avoid deep, soft snow the wolves often follow a hard packed drift or the edge of a road where the snow is more shallow.

Flecks of blood frequently seen in the trails in winter indicated that the wolves were subject to sore feet. In the case of the sled dog traveling in snow, especially in any kind of crusted snow, the hide on the toes is often worn off, sometimes causing the dog to limp considerably. If the crust is severe it may become necessary to protect the feet with moccasins. The feet of the wolves are probably affected by the snow in the same manner as are those of the sled dog, but possibly to a lesser degree. In summer a wolf would occasionally develop a limp and later recover.

Figure 3: Tracks of five wolves crossing a

river bar in the snow. [East Fork River, October 22,

1939.]

History of Wolves in Mount McKinley National Park

Wolves no doubt have been a part of the present Alaska fauna for hundreds of years. Fossil remains are present in the Pleistocene fauna and it is probable that the wolves have persisted in Alaska since that time. The wolf then is not a new animal finding its niche in the fauna, with the possibility of upsetting existing relationships or exterminating some species. It is true that the effects of man's activities may be such as to bring the wolf into new associations with the native fauna, but as yet man's activities have probably not altered conditions sufficiently to seriously change the natural relationships.

The history of the wolves in Mount McKinley National Park during the last 25 years is, in a general way, quite well known. There is also considerable information on the prevalence of the wolf in interior Alaska, although much of this information is conflicting. There is often a tendency to report a great increase of the animals if any are noted, so that during a period when wolves were much less numerous than at present there are many reports of their abundance and great increase. Sometimes the caribou, the principal wolf food, shifts its range and brings wolves along with it into new territory where they are noticed and commented upon. I suppose that the history of the wolves varies a little in different parts of interior Alaska but that the general pattern is similar throughout. Since there are 586,400 square miles in Alaska, and 3,030 square miles in Mount McKinley National Park, which lies near the center of the Territory, it can perhaps be assumed that in its broad aspects the status of the wolves in the park has corresponded rather closely with their status in interior Alaska as a whole.

According to E. W. Nelson (1887) wolves were plentiful over much of Alaska during his sojourn there from 1877 to 1881. At that time wolves were scarce along the west coast due to the absence of caribou. Previously, when the caribou were plentiful there, before the advent of modern firearms among the natives, the wolves were also abundant. In 1880 they were reported most numerous toward the headwaters of the Kuskokwim and Yukon Rivers, which coincides roughly with the limits of the caribou range. At St. Michael, Dr. Nelson examined several thousand wolf skins which were handled by the trading post, and he reported the presence of many wolves inland among the caribou.

Wolves were apparently still plentiful in the early 1900's, and I have no information indicating that they were scarce between 1881 and 1900. An old-timer told me that between 1898 and 1903 wolves were abundant on the Stewart River. Charles Sheldon (1930) found wolves in the Mount McKinley region in 1907 and 1908, but just how prevalent they were it is hard to say. He found little evidence of wolves among the sheep hills along the Toklat River, but found these animals "very abundant" among the caribou at the edge of the mountains on Toklat River. In one night the wolves completely devoured a caribou bull he had shot.

Some time after 1908 the wolf population in the Mount McKinley region and perhaps also in other parts of the interior of Alaska was considerably reduced, probably as a result of natural causes. An old-timer who had hunted sheep in the McKinley region in 1916 and 1917 told me that he saw no wolves or wolf tracks there at that time. In 1920 and 1921 O. J. Murie visited a number of localities in interior Alaska in his travels by dog team and found wolves absent or scarce in most localities. In a trip through Rainy Pass and into the Kuskokwim country in the spring of 1922 he saw no tracks, Mr. Joe Blanchell at Farewell Mountain on the north side of Rainy Pass said that wolves were formerly common in that locality but had now disappeared. There were caribou all through this area so ample wolf food was present. In the past, about 1916 and 1917, a few wolves had destroyed some of Mr. A. H. Twitchell's reindeer herd near Ophir but no wolves were reported in the locality in 1922. This region lies just to the west and north of Mount McKinley National Park.

One trip was made by O. J. Murie through the caribou country between Chatanika and Circle in the spring of 1921, and the Chatanika region was again visited in the fall. No sign of wolf was found in the spring, and in the fall only one was seen, and wolves were heard howling only once. Part of this region was used the year round by caribou. A year or two before wolves had been reported more plentiful.

In March and April 1921, O. J. Murie traveled by dog team from Fairbanks to Tanana Crossing but saw no wolf tracks en route. He found that although wolves were not abundant, they did occur in the upper Tanana region in somewhat greater numbers than they did in the Chena and Chatanika regions nearer Fairbanks, and other regions visited. The upper Tanana region was in habited by caribou at least for part of the year. In 1921 some wolves were reported on the north fork of the Forty Mile River.

On one trip which O. J. Murie and I made in the winter of 1922—23 we started from Nenana in November and traveled to Kokrines, where we visited a reindeer herd, crossed to Alatna, and traveled to the sheep hills in the Endicott Mountains at the head of the Alatna River; visited Bettles and Wiseman on the upper Koyukuk; came down the Chandalar River, where caribou were wintering, to the Yukon; continued to Fort Yukon and Circle, then west through the heart of the caribou country, arriving at Fairbanks on April 26. During the entire winter we saw not a single wolf track, which would indicate that wolves over much of interior Alaska were scarce at that time.

In 1922 and 1923 my brother and I spent considerable time among the sheep hills in Mount McKinley National Park. No tracks and no wolves were seen and none were reported by others.

In more recent years wolves have been more plentiful near Chatanika, where they had been so scarce from 1921 to 1923. During that period wolves had been even scarcer in Mount McKinley National Park.

In 1925, according to reports of the Superintendent, wolves had increased in Mount McKinley National Park to the extent that some tracks were seen in all parts of the park. [According to Soper (1942, p. 132) wolves began to increase in Wood Buffalo Park, Canada, about 1925 and since that time have continued to in crease.] In 1927 it was reported that the wolves were becoming more numerous. A band of 11 was noted by one of the rangers. From 1928 to the present time wolves have been reported each year as plentiful in the park. From the records available, it appears there were no large fluctuations in the population during the period from 1928 to 1941.

The increase of wolves in the park coincided with a general increase in interior Alaska. There are no data to show that wolves are more abundant in Mount McKinley National Park than they are in other favorable localities in interior Alaska. Robert Marshall (1939) found wolf sign common in the Endicott Mountains in 1939. Wolves were reported plentiful in the Wood River country in the fall of 1940.

Since the recovery of the population the actual number of wolves in the sheep hills of the park has never been accurately determined. Estimates vary from 50 to 100. The wide ranging of the wolves and their movements in and out of the park make it extremely difficult to conduct any accurate census. My work did not take me over all the park, but within the sheep hills I would estimate the number of wolves to be between 40 and 60, perhaps nearer the first figure.

To summarize, there have been two periods of wolf abundance and one of scarcity in Alaska in relatively recent years. Records available to me show that wolves were quite abundant in 1880, and probably from 1900 to 1908. Sufficient data, however, are not available to be sure of the exact status for the latter part of this period. Some time after 1908 the population declined and apparently wolves were generally scarce in 1916 and 1917 and up to about 1925, when they again increased. Since 1927 they have remained plentiful over much of interior Alaska. There is no doubt but that wolves were scarce during a period centering in the early 1920's and that since then they have increased and become common.

Causes of Fluctuation in Wolf Numbers

The causes of the scarcity of wolves in interior Alaska between 1916 and 1925, and perhaps some years preceding 1916, are not known. During this period of wolf scarcity the caribou herds, the main food supply, were large so that there was not a shortage of food. There was considerable trapping in the Territory at this time, but judging from the effect of trapping on the present wolf population in Alaska it is doubtful that this had much to do with the scarcity of wolves. Today there is extensive trapping in the interior of Alaska but apparently it has not caused any noticeable reduction in wolf numbers.

Intraspecific intolerance may hold a population in check but would probably not operate to cause a scarcity of the animals. If it operated at all it probably would tend to hold the animals at an optimum level which would be rather high.

The most probable cause of a drastic decimation of the wolves is disease. Mange, distemper, and rabies are some of the diseases which may affect them. Alexander Henry (1897) in his journal refers to scab in wolves. On March 5 (1801) at Pembina, N. Dak., he writes: "A large wolf came into my tent three times, and always escaped a shot. Next day, while hunting, I found him dead about a mile from the fort; he was very lean and covered with scabs."

R. M. Anderson (1938) writes as follows concerning mange in coyotes: "One young male coyote shot by Warden J. E. Stanton when the writer was with him in Cascade Valley early in September was very mangy, being so nearly devoid of hair from nose to tip of tail that the scabby and vesicular skin was plainly visible on every part of the body. Most of the half dozen coyotes seen in this area appeared to be afflicted with mange, and several wardens stated that many of the mangy coyotes lived through the winter, but that the worst cases usually died in the spring. This disease, and perhaps other causes, seems to keep the numbers down, and the reports of the superintendent of the park show that coyotes have decreased in numbers in recent years."

Warburton Pike (1892, p. 53) writes: "There was some sort of disease resembling mange among them (gray wolves) in the winter of 1889—90 which had the effect of taking off all their hair, and judging from the number of dead that were lying about, must have considerably thinned their numbers." This reference indicates that mange might destroy large numbers of wolves, especially in a large population where the conditions for the spread of the affliction would be optimum. Ernest Thompson Seton (1911, p. 351—352) says that in northern Canada mange is common at times. O. J. Murie tells me that he once lost a sled dog from mange.

Seton (1929, p. 288) says that rabies seems to break out among wolves at times. Alexander Henry (1897) as early as 1800 relates the killing of a wolf at camp which was thought to have rabies. Seton gives several instances in which wolves seemed to have had rabies. This disease probably could cause a drastic reduction in a population.

A disease like distemper could no doubt spread rapidly in a large wolf population, especially since the animals travel in packs. Distemper has been known to wipe out entire dog teams and it might affect wolves even more severely. Although the young animals are most susceptible to distemper, older wolves not having been in contact with the disease might be more vulnerable than old dogs which generally are considered immune. In 1924, O. J. Murie lost an entire dog team after he had traveled from Nenana to Hooper Bay, Alaska. Another team made up of older dogs was not affected. In that year a large number of dogs in interior Alaska are reported to have died from the disease, so apparently it was present in epizootic proportions. During April 1934, an outbreak of distemper is said to have prevailed in various sections along the Yukon and Tanana Rivers.

In an article in Field for December 1939, it is pointed out that distemper among dogs in England becomes much more prevalent and more severe in form when the dog population is high. During World War I, when few dogs were kept, there was hardly any distemper and it was nearly always mild. When the dogs were bred up again after the war, there were a great many deaths from distemper. Perhaps the disease was so destructive because the dogs came suddenly into contact with it and had no opportunity to become immunized in any degree. This occurrence suggests a possible threat to any large wolf population.

Three cases of wolves which may have died a natural death came to my attention. However, I found no evidence of disease among the wolves in Mount McKinley National Park.

The last reduction in wolf numbers may have been due to the large number of dogs that were brought into the wolf territory for transportation purposes and spread distemper or some other disease. The decrease in dog travel today may be an element favorable to the wolves. In addition, current trapping operations may be just sufficient to keep the wolf numbers from reaching a peak where they would be more susceptible to drastic reduction. This is, of course, theoretical, but seems worthy of consideration.

In connection with the problem of control of the wolf population it is of interest to consider the coyotes in Yellowstone National Park. During the long period that one or two hundred coyotes were destroyed annually in the park the coyote numbers remained high. When artificial control of the coyotes was stopped in 1935 many persons expected a great increase in their numbers. They did continue to be common, but apparently were no more plentiful than when artificial control was exercised. Now, in 1942, 7 years after control was stopped, there appears to have been a slight drop in the coyote population, judging from reports that have reached me, so that there may be fewer coyotes now than when artificial control was practiced. It is apparent that some natural controls, possibly disease, among others, are operating on these coyotes to hold their numbers in check. In a similar manner wolf numbers in Alaska may be subject to drastic natural controls and the population may again be greatly reduced through some natural factor like disease.

Breeding

In Mount McKinley National Park the young of wolves apparently are born in early May. Three litters of which the approximate time of birth was known had been born in early May. According to Bailey (1926, p. 155) this is more than a month later than in the Northern States. The gestation period of about 63 days (Seton, 1929, p. 274) would place the mating season early in March. Two females in the park each had four pups, and three had six pups.

A captive female which I raised and which was later kept at Mount McKinley National Park Headquarters, did not come in heat the first year but did so in early March in her second year and was in heat about 2 weeks. This agrees with the statement by Bailey (1926, p. 155) that wolves do not breed until they are 2 years old. Another captive female owned by Mrs. Faith Hartman of Fairbanks likewise did not come in heat the first year but bred with a dog the second year. The first 2 weeks that this wolf was in heat she fought off the dog but mated each day during the third week (March 9 to March 15). The male continued to pursue her on the following 3 days but there was no further mating after the fifteenth. She whelped four pups on May 15. The first one was born at 12:30 p. m., and the others at intervals of 45 minutes to 1-1/2 hours. This observation placed the gestation period between 60 and 66 days.

Home Life

In 1940 and 1941 wolves were found denning on Toklat River but extensive observations on these Toklat wolves were not made. In 1940 a few notes were made regarding a family on Savage River, but in 1940 and 1941 much time was devoted to observing a family at a den on the East Fork of the Toklat River (known locally and hereafter referred to as East Fork or East Fork River). These three wolf groups will be discussed separately.

TOKLAT RIVER DEN

In 1939 no special effort was made to find dens because there were so many other phases of the field work which could not be neglected. The finding of dens sometimes seems simple, and at other times most difficult. To illustrate, in 1940 ex-trapper Frank Glaser, Agent of the Fish and Wildlife Service, and Wildlife Ranger Harold Herning of the National Park Service spent all their time from early March to early August in search of dens in Mount McKinley National Park. During this period they worked hard but found only one family of wolves and that was in a Toklat River den which was known to have been occupied on at least two previous occasions. Of course, their inability to find more may have indicated a scarcity of dens.

In a letter to O. J. Murie, former Ranger Lee Swisher gives an interesting description of his efforts to find this particular den on the Toklat River: "This past season I had great difficulty in locating a den. On two occasions, I saw (with the aid of binoculars) an old wolf carry meat from a sheep carcass in Polychrome Pass, then go down Toklat River. I spent many days searching over the country where it seemed the den should be. There was a well-beaten trail for over 5 miles along the Toklat bars, then onto a bench where I could follow it no more. One morning while scouting along this bench close to the timber through some weeds I had no difficulty in following this trail which kept in the timber for about 2 miles where it then emerged onto the river bars again for another 5 miles or more where I located the den on a small timbered island along the river. I estimated that this wolf was carrying food to its young over 12 miles."

The Toklat River family was living about 12 miles north of the highway and 2 miles north of the sheep hills, on an island of spruces about 1 mile long and a third of a mile or less in width. Gravel bars surround this spruce island and sometimes the numerous channels of the Toklat River flow on both sides of it. The general level of the island rises only 2 or 3 feet above the gravel bars.

Following directions given me by former Ranger Lee Swisher, I first visited the den in the fall of 1939. It was located about 20 yards from the edge of the timber, in sandy loose soil in which a few cottonwoods grew along with the spruces. The wolves had renovated a fox den for their own use. The foxes had, as usual, a number of entrances, there being eight or nine of them in an area 20 feet across. One of them, leading under the roots of a spruce, was enlarged by the wolves when they took possession. It led to a chamber in the center, about 3 feet below the surface. According to reports, this chamber had been exposed by a trapper about 1937, and seven pups and a gray female were destroyed. In 1940 the wolves had used the same entrance but had dug 10 feet at right angles to the former burrow. Four pups were inadvertently removed from the den before I had an opportunity to observe it. There was no nest material in the chamber. The entrance was 16 inches high and 21 inches wide.

A narrow trail through the woods, 7 to 9 inches wide and 280 yards long, connected this den with another which also had been first occupied by foxes and later was taken over by wolves. It was located in a sandy rise in which a few cottonwoods grew with the spruces. One of the many holes had been enlarged and there was a large mound of dirt at its mouth. The entrance was 15 inches high and 20 inches wide. At least five well-defined trails led out in different directions. In 1940 this den showed some use, but this may have been in connection with the den from which the four pups were taken. Later in the summer it was evident that it had not been used after the first visit to it in May.

In 1941 the second den was occupied by a family on June 23. When I approached the den I saw four brownish pups playing near the entrance. The main burrow had been enlarged some since the previous year, as had two or three of the smaller ones which were used by the pups. Along a wash in the woods 50 yards away there were five beds in the dirt, all dug out a little, one to a depth of 8 inches. It was not known how many adults were in the family. The den near this one, raided in 1940, was unoccupied.

SAVAGE RIVER WOLF FAMILY

In 1939 a pair of black wolves and some black pups were reported on Savage River and apparently the same pair was there the next year. Although it was evident that a wolf family was living on Savage River in the spring of 1940, I could not afford to take much time to search for its habitation since I was then busy making observations at a den on East Fork River. But on August 14, near the head of Savage River, I discovered the family. All along, on the gravel bars, wolf tracks had been plentiful. It was evident that pups and adults had traveled much up and down Savage River for a distance of 6 or 7 miles. In some stretches there was a definite trail in the gravel, and fresh trails had been made through vegetation, leaves and stems having recently been tramped down. Here and there a scat was found.

I first had a glimpse of the head of an adult black wolf on the edge of an extensive growth of willows bordering the bar. After watching me a few moments the animal disappeared, but by climbing a slope, I obtained a view of it running off, a half mile away. I continued up the bar to some old caribou corrals and, about 3 hours later, returned to the willows where I had seen the wolf. There were many pup tracks in the sand and a number of scats, so that the spot appeared to be a rendezvous. Presently I heard low growling in the willows just ahead of me. I knew it was a wolf or grizzly, but in either case I did not wish to disturb it, so I backed away cautiously, moved slowly toward a ridge nearby, and then climbed a short distance up the slope. Down river I heard a wolf howl, and a little later from the slope where I was screened by willows I saw a black wolf running. A half mile away it stopped to bark so I was sure the pups were near me. Presently a black pup passed an opening in the willows near the place where I had heard the growling and a short distance away on the bar other pups were discovered feeding on the remains of a large bull caribou. There were six pups, all of them black. Some were lying down, some feeding, some walking about aimlessly. One carried a piece of caribou across the bar, possibly to cache it. Two played briefly. Those walking about wagged their tails slowly. They seemed too full for much playing. Later another black adult joined the first one. Both barked, sometimes a series of barks, terminating in a long howl. The parents moved up a knoll across the narrow valley and watched. At 5 p. m. I departed, without disturbing the pups, which for 3 hours had been oblivious of my presence about 200 yards from them.

The following day I hiked the 9 miles up the bar in hopes of getting moving pictures. Carefully I made my way to where I had watched the pups feeding on the caribou and arrived there at about 10:30 a. m. After watching a half hour I saw a black wolf galloping down a tributary on the other side of the valley. It was coming toward a knoll on which I saw another black wolf. The latter was lying about 30 feet above a narrow bar covered with willows 7 or 8 feet tall. After lying there for 15 minutes, frequently looking around, it moved out of sight. Soon the wolves howled in chorus.

I waited until 1:30 p. m. hoping the wolves would return to the carcass. At that time rapidly moving heavy clouds were rising above the horizon so I decided to approach the wolves for a picture before the sun disappeared. As I neared the mouth of the side stream where I had seen them a pup scurried across the gravel from one clump of willows to another. Two other pups scurried across openings. Continuing slowly through the willow-covered bar, I saw two adults and two pups running away in the distance. For a better view I climbed the knoll where the wolf had been lying. I continued climbing and presently saw the two adults returning toward me at a gallop. One was a large gray animal. They barked at me, then moved down to where the pups had been. Later I saw two black adults galloping downstream a half mile below me. The pups had dispersed; one of them I heard howling later 2 miles down stream.

During the winter a trapper saw a band of seven black wolves and one gray one on lower Savage River, not far from the park boundary, 17 or 18 miles north of where they were seen in the summer. These were probably the group I had observed at the head of Savage River. Somewhere along Savage River is a wolf den which apparently is used year after year.

The Savage River family was of special interest because of the presence of three adults, all concerned over the welfare of the pups. The sex and age of the extra adult was not known so its relationship was not determined. There could have been two families living together, but the uniformity in the appearance of the six pups indicates that they were of one litter. The extra wolf may have been a pup of the previous year, but judging from the relationships at the East Fork den, where there were extra adults, it seems likely that the extra wolf was not a yearling but was an adult living with the pair year after year.

EAST FORK RIVER DEN—1940

Finding the Den.—In front of our cabin at East Fork River, on May 15, 1940, wolf tracks were seen in the fresh snow covering the gravel bars. The tracks led in both directions, but since there was no game upstream at the time to attract the wolves, it appeared that some other interest, which I hoped was a den, accounted for their movement that way. I followed the tracks up the bar for a mile and a half directly to the den on a point of the high bank bordering the river bed. In contrast to the Toklat den, which was located in the woods in a flat patch of timber, this one was 2 miles beyond the last scraggly timber, on an open point about 100 feet above the river where the wolves had an excellent view of the surrounding country. Apparently a variety of situations are chosen for dens for I was told of two others which were located in timber, and of a third which was in a treeless area at the head of a dry stream.

Foxes had dug the original den on the point, and wolves had later moved in and had enlarged a few of the burrows. It seems customary in this region for wolves to preempt fox dens. Former Ranger Swisher, who had found at least four wolf dens, said that all of them had originally been dug by foxes. There are many unoccupied fox dens available so it is not strange that they are generally used by the wolves. The soil at the sites is sandy or loamy, at least free of rocks, so that digging is easy. Only a little enlarging of one of the many burrows is required to make a den habitable for a wolf. Although the adult wolves can only use the enlarged burrow, the whole system of burrows is available to the pups for a few weeks. This advantage is incidental and probably has no bearing on the choice of fox dens as homes.

Figure 4: Locale of East Fork wolf den,

which was on the promontory at left of picture (see arrow). The author's

observation point was on the ridge directly opposite, between the two

branches of the East Fork of the Toklat River. The mountains of the

Alaska Range, on the skyline, are used in summer by sheep. [May 5,

1940.]

When I approached this den the black male wolf was resting 70 yards away. He ran off about a quarter of a mile or less and howled and barked at intervals. As I stood 4 yards from the entrance, the female furtively pushed her head out of the burrow, then withdrew it, but in a moment came out with a rush, galloped most of the way down the slope, and stopped to bark at me. Then she galloped toward the male hidden in a ravine, and both parents howled and barked until I left.

From the den I heard the soft whimpering of the pups. It seemed I had already intruded too far, enough to cause the wolves to move. As I could not make matters much worse, I wriggled into the burrow which was 16 inches high and 25 inches wide. Six feet from the entrance of the burrow there was a right angle turn. At the turn there was a hollow, rounded and worn, which obviously was a bed much used by an adult. Due to the melting snow it was full of water in which there was a liberal sprinkling of porcupine droppings. A porcupine had used the place the preceding winter. Its feeding signs had been noted on many of the nearby willows. From the turn the burrow slanted slightly upward for 6 feet to the chamber in which the pups were huddled and squirming. With a hooked willow I managed to pull three of the six pups to me. Not wishing to subject all of them to even a slight wetting, and feeling guilty about disturbing the den so much, I withdrew with the three I had. Their eyes were closed and they appeared to be about a week old. They were all females, and dark, almost black. One appeared slightly lighter than the other two and I placed her in my packsack to keep for closer acquaintance. The other two were returned to their chamber and I departed.

After my intrusion it seemed certain that the family would move, so the following morning I walked toward the den to take up their trail before the snow melted. But from a distance I saw the black male curled up on the point 15 yards from the entrance, so it was apparent that they had not moved away after all. In fact, they remained at the den until the young were old enough to move off with the adults at the normal time.

Figure 5: The person (right center of the

picture) is standing near one of the entrances to the East Fork wolf

den. The lookout ridge is across the bar to the left, and sheep

mountains above Polychrome Pass are on the skyline. [August 26,

1940.]

On a ridge across the river from the den, about a half mile or less away, there were excellent locations for watching the wolves without disturbing them. There was also a view of the landscape for several miles in all directions.

Between May 15, when the den was discovered, and July 7, when the wolves moved a mile away, I spent about 195 hours observing them. The longest continuous vigil was 33 hours, and twice I observed them all night. Frequently I watched a few hours in the evening to see the wolves leave for the night hunt. Late in the summer and in the early fall after the family had left the den, I had the opportunity on a few occasions to watch the family for several hours at a time.

Composition of the East Fork Family.—So far as I am aware it has been taken for granted that a wolf family consists of a pair of adults and the pups. Perhaps that is the rule, although we may not have enough information about wolves to really know. Usually when a den is discovered the young are destroyed and all opportunity for making further observations is thereby lost.

Figure 6: Five-year-old girl standing in the entrance of one of the burrows of the East Fork wolf den. [August 26, 1940.] |

The first week after finding the East Fork den I remained away from its vicinity to let the wolves regain whatever composure they had lost when I intruded in their home. On May 26, a few days after beginning an almost daily watch of the den, I was astonished at seeing two strange gray wolves move from where they had been lying a few yards from the den entrance. These two gray wolves proved to be males. They rested at the den most of the day. At 4 p. m., in company with the black father wolf, they departed for the night hunt. Because I had not watched the den closely the first week after finding it I do not know when the two gray males first made their appearance there, but judging from later events it seems likely that they were there occasionally from the first.

Five days later, a second black wolf—a female—was seen, making a total of five adults at the den—three males and two females. These five wolves lounged at the den day after day until the family moved away. There may have been another male in the group for I learned that a male had been inadvertently shot about 2 miles from the den a few days before I found the den.

Late in July another male was seen with the band, and a little later a fourth extra male joined them. These seven wolves, or various combinations of them, were frequently seen together in August and September. Five of the seven were males. The four extra males appeared to be bachelors.

The relationship of the two extra males and the extra female to the pair is not known. They may have been pups born to the gray female in years past or they may have been her brothers and sister, or no blood relation at all. I knew the gray female in 1939. She was then traveling with two gray and two black wolves which I did not know well enough to be certain they were the same as those at the den in 1940. But since the color combination of the wolves traveling together was the same in 1940 as in 1939, it is quite certain that the same wolves were involved. So apparently all the adult wolves at the den in 1940 were at least 2 years old. In 1941 it was known that the extra male with the female was at least 2 years old for he was an easily identified gray male which was at the den in 1940. The fact that none of the 1940 pups was at the 1941 den supports the conclusion that the extra wolves at the 1940 den were not the previous year's pups.

The presence of the five adults in the East Fork family during denning time in 1940 and three in 1941, and three adults in the Savage River family, suggests that it may not be uncommon to find more than two adults at a den. The presence of extra adults is an unusual family make-up which is probably an outcome of the close association of the wolves in the band. It should be an advantage for the parents to have help in hunting and feeding the pups.

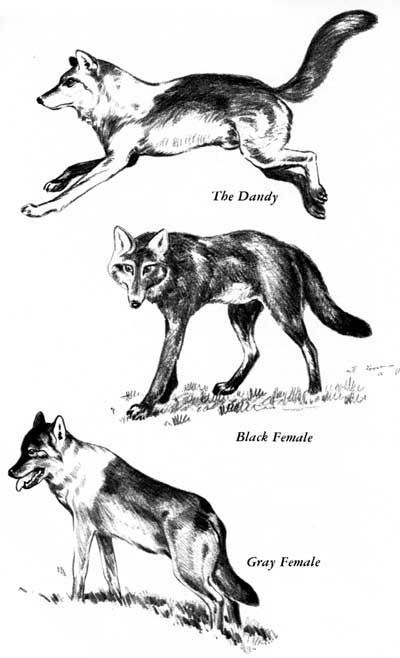

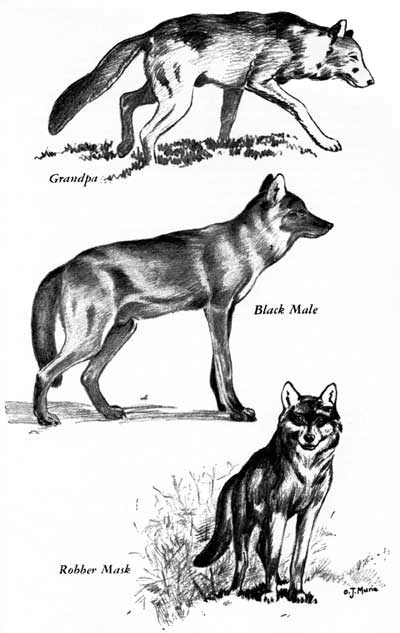

Description of the Individual Wolves.—Wolves vary much in color, size, contour, and action. No doubt there is also much variation in temperament. Many are so distinctively colored or patterned that they can be identified from afar. I found the gray ones more easily identified since among them there is more individual variation in color pattern than in the black wolves.

The mother of the pups was dark gray, almost "bluish," over the back, and had light under parts, a blackish face, and a silvery mane. She was thick-bodied, short-legged, short-muzzled, and smaller than the others. She was easily recognized from afar.

The father was black with a yellowish vertical streak behind each shoulder. From a distance he appeared coal black except for the yellow shoulder marks, but a nearer view revealed a scattering of silver and rusty hairs, especially over the shoulders and along the sides. There was an extra fullness of the neck under the chin. He seemed more solemn than the others, but perhaps that was partly imagined by me, knowing as I did that many of the family cares rested on his shoulders. On the hunts that I observed he usually took the lead in running down caribou calves.

The other black wolf was a slender built, long-legged female. Her muzzle seemed exceptionally long, reminding me of the Little Red Riding Hood illustrations. Her neck was not as thick as that of the black male. This female had no young in 1940, but had her own family in 1941.

What appeared to be the largest wolf was a tall, rangy male with a long silvery mane and a dark mantle over the back and part way down over the sides. He seemed to be the lord and master of the group although he was not mated to any of the females. The other wolves approached this one with some diffidence, usually cowering before him. He deigned to wag his tail only after the others had done so. He was also the dandy in appearance. When trotting off for a hunt his tail waved jauntily and there was a spring and sprightly spirit in his step. The excess energy at times gave him a rocking-horse gallop quite different from that of any of the others.

The other gray male at the den I called "Grandpa" in my notes. He was a rangy wolf of a nondescript color. There were no distinctive markings, but he moved as though he were old and a little stiff. Sometimes he had sore feet which made him limp. From all appearances he was an old animal, although in this I may be mistaken.

One of the grays that joined the group in late July was a large male with a light face except for a black robber's mask over the eyes. His chest was conspicuously white. He moved with much spring and energy. The black mask was distinctive and recognizable from a distance.

The other wolf, which joined the group in August, was a huge gray animal with a light yellowish face. In 1941 he was mated to the small black female which had no young the preceding year.

Figure 7: Wolf portraits.

Figure 8: Wolf portraits.

All these wolves could be readily distinguished within the group but some of the less distinctively marked ones might have been confused among a group of strange wolves. The black-faced gray female, the robber-masked male, and the black-mantled male were so characteristically marked that they could be identified in a large company.

I suppose that some of the variability exhibited in these wolves could have resulted from crossings in the wild with dogs. Such crosses in the wild have been reported and the wolf in captivity crosses readily with dogs. Some years ago at Circle, Alaska, a wolf hung around the settlement for some time and some of the dogs were seen with it. The people thought that the wolf was a female attracted to the dogs during the breeding period. However, considerable variability is probably inherent in the species, enough perhaps to account for the variations noted in the park and in skins examined. The amount of crossing with dogs has probably not been sufficient to alter much the genetic composition of the wolf population.

Activity at the Den.—Many hours were spent watching the wolves at the den and yet when I undertake to write about it there does not seem to be a great deal to relate, certainly not an amount commensurate with the time spent observing these animals. There were some especially exciting and interesting incidents such as the times when the grizzlies invaded, and a strange wolf was driven away. The departure for the night hunt and the reactions of the wolves to caribou were always of interest. These special incidents are described on pages 43 and 204. But the routine activity at the den was unexciting and quiet. For 3 or 4 hours at a time there might not be a stir. Yet it was an inexhaustible thrill to watch the wolves simply because they typify the wilderness so completely.

The periods of watching were sufficiently long to yield behavior data of statistical value. I believe that the routine activity at this den was fairly well known.

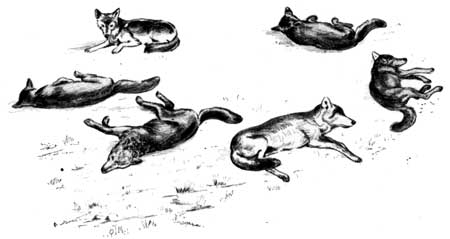

Just as a laboring husband comes home to the family each evening after working all day, so do the wolves come home each morning after working all night. The wolf comes home tired, too, for he has traveled far in his hunting. Ten or fifteen miles is a usual jaunt for a hunt, and he generally takes part in some chases in which he exerts himself tremendously. His travels take him up and down many slopes and ridges. When he arrives at the den he flops, relaxes completely, and may not even change his position for 3 or 4 hours. Often he may not even raise his head to look around for intruders. Sometimes he may stretch and yawn, change his position, or shift his bed a few yards. Usually in summer he lies stretched out on his side, but occasionally may be curled up as in winter. Frequently a wolf will move over to a neighbor, perhaps sniff of him, getting for a response only a lazy indication of recognition by an up-and-down wag of the tail, and lie down near him. An animal may move from the point of the bluff down to the gravel bar, or while the overflow ice still remains on the bars, he may lie in the snow for a while. When the caribou grazed near the den a wolf might raise up a bit for a look, but generally a caribou was not sufficient reason for him to disturb his resting The female may be inside the den, or on the outside, for hours at a time. The five adults might be sleeping a few hundred yards apart or three or four of them might be within a few yards of each other. Of course all the adults were not always at home, one or two might be out for a short day light excursion or fail to come home after the night hunt. That, in brief, is the routine activity at the den.

The first few weeks the gray female spent much time in the den with the pups, both during the day and at night. When she was outside she usually lay only a few yards from the entrance, although she sometimes wandered off as far as half a mile to feed on cached meat. When the rest of the band was off on the night hunt she remained at home, except on three occasions that I know of—June 1, June 8, and June 16. Each time she went off with the band she ran as though she were in high spirits, seeming happy to be off on an expedition with the others. On these three occasions the black female remained through the night with the pups.

The father and the black female were seen to enter the den when the pups were only a couple of weeks old. Later, when the pups were old enough to toddle about outside, the father and the two females were very attentive to them. The two gray males often sniffed at the pups which frequently crawled over all five wolves in their play. Sometimes the pups played so much around an adult that it would move away to a safe distance where it could rest in greater peace.

The attentiveness of the black female to the pups was remarkable. It seemed at times that she might have produced some of them and I do not absolutely know that she did not. But her absence from the den the first 10 days (so far as I know), the uniformity in the size of the pups, and the greater concern and responsibility exhibited by the gray female, strongly indicates that the gray one had produced all the pups. The companionship of these two adults suggests that two females might at times den together, although having pups in one den would be somewhat in convenient. Rather, one would expect them to den near each other as these two females did in 1941.

Wolves have few enemies and consequently are frequently not very watchful at the den or elsewhere. Often I approached surprisingly close to the wolf band before being discovered. Several times I was practically in the midst of the band before I was noticed. Once, after all the others had run off, one which must have been sound asleep got up behind me and in following the others passed me at a distance of only about 30 yards. These wolves were scarcely molested during the course of the study, so they may have been less watchful than in places where they are hunted. But their actions were probably normal for primitive conditions. When alert their keen eyes do not miss much.

Before the vegetation changed from brown to green the gray wolves, when curled up or when only the back showed, were especially difficult to see against the brown background. But if they were stretched out so as to expose the light under parts they were plainly visible. The black ones were usually more conspicuous but under certain conditions of poor light or dark backgrounds the gray wolves were the more conspicuous. At the den all the wolves were sometimes difficult to see because of slight depressions in which they lay, and the hummocks hiding them. Once when all five adults were lying on the open tundra slope above the den not one could be seen from my lookout. Often only two or three of the five could be seen until some movement showed the position of the others.

The strongest impression remaining with me after watching the wolves on numerous occasions was their friendliness. The adults were friendly toward each other and were amiable towards the pups, at least as late as October. This innate good feeling has been strongly marked in the three captive wolves which I have known. Undoubtedly, however, wolves sometimes have their quarrels.

Food Brought to the Den.—It is likely that all the wolves brought food to the East Fork den. It was necessary to bring food for the pups, and for the female remaining with them. The gray female, the black male, and the mantled male were all observed carrying food. Some of the food was brought directly to the den where the young were often seen feeding on it. Much of it was cached 100 or 200 yards away, and some of it as much as a half mile away. The wolf remaining at home during the night was seen to go out to these food caches, and occasionally one of the other wolves might eat a little from them during the day. The wolves that hunted probably ate their fill near the kill.

Relatively few bone remains were to be found at any of the dens. At the Lower Toklat den, there was the skin of a marmot, four calf caribou legs, leg bones of an adult caribou, and 300 yards away the head of a cow caribou. Remains, mainly hair, of an adult caribou were found on the bar about a quarter of a mile from this den. At the East Fork den there were scarcely any bones around the den after the family left, and there were only a few where they lived after leaving the den. At this den, where the food was mainly calf caribou, probably most of the long bones were eaten. Former Ranger Swisher told me that at a den he had found several years ago there were a number of legs of mountain sheep.

Departure for the Night Hunt.—There was considerable variation in the time of departure for the night hunt. On a few occasions the wolves left as early as 4 p. m., and again they had not left at 9 or 9:30 p. m. They were seen departing for the hunt 11 times. Five of these times they left between 4 p. m. and 5:45 p. m., and six times they left between 7 p. m. and 9:30 p. m. Usually the hunting group consisted of the three males, but sometimes one of the females was in the group. The wolves hunted in a variety of combinations—singly, in pairs, or all together. In the fall the adults and young traveled together much of the time, forming a pack of seven adults and five pups.

Usually the wolves returned to the den each morning, but three wolves which left the den at 4 p. m. on May 26 had not returned to the den the following day by 8 p. m. when I left the lookout, after watching all night and all day. The wolves had probably spent the day near the scene of their hunt. These wolves were again at the den on May 28.

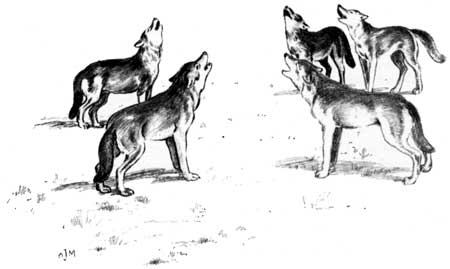

Considerable ceremony often precedes the departure for the hunt. Usually there is a general get-together and much tail wagging. On May 31 I left the lookout at 8:30 p. m. since the wolves seemed, after some indications of departure, to have settled down again. But as I looked back from the river bar on my way to camp I saw the two blacks and the two gray males assembled on the skyline, wagging their tails and frisking together. There they all howled, and while they howled the gray female galloped up from the den 100 yards and joined them. She was greeted with energetic tail wagging and general good feeling. Then the vigorous actions came to an end, and five muzzles pointed skyward. Their howling floated softly across the tundra. Then abruptly the assemblage broke up. The mother returned to the den to assume her vigil and four wolves trotted eastward into the dusk.

On June 2 some restlessness was evident among the wolves at 3:50 p. m. The two gray males and the black male approached the den where the black female and some pups were lying. Then the black male lay down near the den; the mantled male walked down on the flat 100 yards away and lay down, and Grandpa, following him, continued along the bar another 150 yards before he lay down. At 6:43 p. m. the mantled male sat on his haunches and howled three times, and in a few minutes he sent forth two more long mournful howls. Grandpa stood up and with the mantled male trotted a few steps toward five passing caribou. Then the mantled male howled six or seven times, twice while lying down. The gray female trotted to the gray males, and the three of them stood together wagging their tails in the most friendly fashion. The mantled one howled and they started up the slope. But before going more than 200 yards they lay down again. A few minutes later, at 7:15 p. m., the mantled male howled a few times and walked to the den followed by Grandpa. The latter seemed ready to go whenever anyone decided to be on the move. At the den the black female squirmed and crouched before the mantled male, placing both her paws around his neck as she crouched in front of him. This hugging with the front paws is not an uncommon action.

Figure 9: "All together."

Later the two gray males and both black wolves were in a huddle near the den entrance, vigorously wagging their tails and pressing against each other. The gray female joined them from up the slope and the tail wagging became more vigorous and there was a renewed activity of friendliness. At 7:30 p. m. the mantled male descended the slope to the bar and started to trot away. He was shortly followed by the black male and Grandpa. The black female followed the departing males to the bar, then returned to the gray female at the den. Both females remained at the den this time.

On June 8 at 7:15 p. m. Grandpa approached the mantled male, wagging his tail. The mantled male stood stiffly erect and wagged his tail slowly, with a show of dignity. The two walked over to one of the blacks and lay down. The mantled male turned twice around like a dog, before lying down, then rose and turned around again before settling down.

There was no movement until 9 p. m., when Grandpa rose, shook himself, and walked over to the mantled male. They wagged tails and were joined in the ceremony by the black female. The mantled male sniffed at the black male who was still resting. He rose and the tail wagging began again. The gray female hurried down the slope to the others and the tail wagging became increasingly vigorous. The friendly display lasted 7 or 8 minutes and, led by Grandpa, who seemed specially spry this evening, they started eastward. The black female followed a short distance, then stopped and watched them move away. A quarter of a mile farther on the four wolves commenced to play on the green flat. The black female trotted rapidly to them and joined in the play. After a few minutes of pushing and hugging the four again started off, this time abreast, spaced about 50 to 75 yards apart. The black female followed for a short distance and lay down. She appeared anxious to follow. After 15 minutes she returned to the den, and two or three pups came out to join her.

The gray female at first led the wolves up the long slope toward Sable Pass, but later the two gray males were in front, running parallel about 200 yards apart. They trotted most of the time, but galloped up some of the steeper slopes. On a snow field they stopped for a time to frolic. The black female remained at the den all night. The hunters returned at 9:15 the following morning. The gray female hurried unhesitatingly to the burrow, like a mother who has been absent from her child for a few hours. The black male flopped over on his side a short distance from the den and lay perfectly still and relaxed. About 1 mile north of the den the mantled male was stretched out on his side on a high point. The wolves had been away on the hunt about 12 hours.

At 4 p. m. on June 16 the two gray males, the black male, and the gray female left the den, led by the mantled male. Soon the female took the lead and she headed for a spot where some eagles were feeding. She nearly captured one of the eagles by jumping high in the air after it as it took off. These wolves went directly to Teklanika River some 7 or 8 miles from the den.

It was evident that by evening the wolves were rested and anxious to be off for the night hunting. The time of their departure for the hunt no doubt varied from day to day depending somewhat upon how soon they came in from the previous night's expedition. Theirs is not a lazy life for the nature of their food demands that they travel long distances and work hard for it, but they seem to enjoy their nightly excursions.

The Family Leaves the Den.—The extended wanderings of the pups below the den on the river bar, early in July, indicated that the family might soon move away. I had refrained from approaching close enough for taking pictures, but with their departure seemingly imminent I made a careful stalk to the bank opposite the den on July 8. I was a day late, for although I waited until evening not a wolf was seen.

In the evening I looked over at the den from Polychrome Pass. At 8 p. m. the mantled male came from the direction of Sable Pass. He stopped several times near the den and appeared to be howling but he was too far away to be heard. He moved to a knoll south of the den and sniffed about in a short ravine where the pups had often been seen. It appeared that the family had moved during his absence. He dropped down to the bar and followed southward along the bank for a half mile, then abruptly turned and climbed the bank at a gallop. Above, on the sloping tundra, he joined the female and the pups and for a time they wagged tails and romped together. The days at the den were over.

The following morning, July 9, I walked up the river past the wolf den and across the broad level bar covered with grass and dryas, toward the spot where I had seen the wolf family the previous evening. The gray female and both black wolves were with the pups and saw me when I came in view around the point on which the den is located. They sat on their haunches watching my approach. There had been no chance to make a stalk so I continued forward, hoping that the wolves would stay close enough to the pups to permit me to take some pictures. After watching me advance for about 200 yards the three adults ran up the long open slope, stopping at intervals to bark and howl. The black male, after angling up the slope, galloped along the hill in my direction, keeping his elevation above me and frequently stopping to bark. I continued forward and passed the three wolves which were now barking at me from directly up the slope. The gray female joined the black male, but the black female moved higher up. When I was almost opposite and within about a quarter of a mile of the pups (they had taken refuge in a burrow 10 feet long and open at both ends) the black male galloped down the slope to the bar, followed closely by the gray female. They came out on my trail and headed directly into the wind toward me at a gallop. The female took the lead and with noses to the ground they came on at a rapid, brisk trot. I set up the movie camera and saw them in the finder, running silently and swiftly. Their purposefulness and intent manner worried me some, and I began to wonder if they would turn aside. They were accustomed to seeing people, so lacked the timidity of most wolves. I wondered if the two grays and the other black might not join the two coming toward me. Generally I carried an automatic pistol in my packsack, and as I had not checked on the matter before starting out, I now hurriedly looked and was relieved to find it was there. By that time the wolves were about 100 yards away and, circling to one side, they commenced to bark. The female passed me and the male remained on the other side. Both continued howling and barking, about 200 yards away. After exposing my film I walked down the bar. The female remained opposite the pups, howling at intervals, and the male kept abreast of me for a half mile as I went down the bar to camp. The black female remained on the slope, howling. When I returned to the spot an hour and a half later with more film, the wolves had all departed. The pups were not seen again until August 22, when they were found about 5 miles away. The adults in the interim were often seen, but the pups were not traveling with them. They apparently were at some rendezvous.

A Group of Adults Observed on July 30.—At 6 a. m. on July 30 deep howling was heard a short distance above our camp. With my camera I hurried toward the sound and came upon the mantled male on the flat below Sable Mountain. Presently he was joined by the gray female and Grandpa. They howled together and were answered by a wolf farther up the gentle slope. The three wolves moved nearer the base of Sable Mountain, where they joined the black-masked wolf. They lay on the tundra, in a depression just sufficiently deep to hide them from me.

Later the black male came from the west and joined them. His coming was heralded by the loud chirping of the ground squirrels all along his route. The black male walked slowly to the mantled male and was surrounded by the other wolves, all wagging their tails. The black male walked about 30 yards away and they all lay down again. Later they stood up and after some more friendly tail wagging lay down.

Early in the afternoon Ranger Harold Herning and I advanced cautiously toward the band for pictures, taking advantage of the shallow swale below the animals. We were about 100 yards from them when we noticed the black male peering over the rise and saw him trot to one side and watch us. The others, who had not seen us, trotted over to the black male. There was a slight altercation accompanied by a little growling and snarling when they came together. Grandpa lay down, but about that time all the wolves saw us. They watched us for a few seconds before trotting up the slope, still not much afraid. They continued over a rise and disappeared up the mouth of a short canyon. When we came in view again they were moving slowly up the canyon. Near its head they laboriously climbed a steep rock slope, using a switch-back technique. On top they followed the ridge along the sky line for some time before disappearing.

The black female was absent from the group; she probably was with the pups. The band was resting up for the night hunt and may not have been far from the pups. From this time on the black-masked male was frequently with the band.

The Pups Found Again.—On August 22, on the flat below Polychrome Pass, the pups were seen for the first time since they left the den on July 9, although some of the adults had frequently been seen. The wolves seemed to have been attracted to this vicinity by the refuse from a nearby road camp. The men at the road camp had been hearing the wolves howling for several nights so the family probably had been headquartering there for a few days before I saw them.

At 4 p. m. a wolf howled three times from a point southeast of the refuse heap, and an hour later the gray female, followed by a pup, appeared from behind a bench. She apparently was on her way to the refuse heap. Out on the flat the mantled male walked slowly into view from behind the same bench, followed by two black pups 100 yards to the rear. He walked slowly, with head down and tail held horizontally. Some distance to the west the two adults met and moved westward. The pups did not follow but returned to the east and lay down in sight of us.

The following day, with two companions I returned to Polychrome Pass and saw the wolves lying on the tundra among the dwarf birches and short willows. As we watched, a large gray wolf with a light face walked toward the others. He looked over the flat where the other wolves rested and lay down on the bench a short distance from them. This gray wolf was the second addition, so there were now seven adults in the band.

We stalked the wolves, coming first to the large gray one on the bench. He rose 50 yards or so ahead of us and loped away toward the others on the flat and aroused them. They ran off from in front of us, all headed southward. I hurried over the flat to get a picture of a black pup which was standing uncertainly watching the others run. While I was photographing the pup the mantled male got up behind me a short distance and ran close past me between me and my companions. He must have been sound asleep to be aroused so tardily. Five of the adults and some of the pups stopped on a knoll about a mile away. The parents hung back, barking at us, probably solicitous over some of the pups which had been left some distance behind. When I walked toward them they barked and howled and those on the knoll howled in the usual mournful chorus. Soon the parents hurried to join the others. The pups in the rear must have caught up with the band by this time. The green grass at the base of a bench near the place where the wolves had been lying was flattened and much worn, showing that the wolves had spent much time there. The bones of a fresh front leg of a large caribou were noted nearby, and several droppings were found.

Some Activities Observed September 17.—On September 17 the family was seen again on the flat below Polychrome Pass. At 8 a. m. three pups trotted briskly down a gravel bar. They stopped at one spot and sniffed zealously, apparently in search of morsels where they had feasted during the night. Nothing was there except rich sniffing. They climbed a bluff above the bar, scared an eagle from its perch, and sniffed about on a point of rock. They returned to the bar and hurried to the gray female and the black-masked male who were lying within a few feet of each other. The mantled male had just lain down on a bench above these two and was hidden in the dwarf birch. The three black pups, now almost the size of their mother, swarmed all over her, and later touched noses with the black-masked male who had joined the band after the pups left the den.

The mother led the way to the base of a bench and there uncovered some morsels of food which were at once eaten by the pups. They resumed their play all over the mother, after which they all lay down near the black-masked male, forming a circle. Another black pup who had been off by itself hunting mice approached the group and smelled of the black-masked male who sniffed at it, causing it to roll over on its back with diffidence. The pup then smelled of each of the others, who barely noticed the salutation by raising the nose a trifle. A yellow pup who had been hunting mice also joined the group. It first smelled noses with the black-masked male, who raised his nose to it and as he lay flat on his side, wagged his tail a few times. Then the pup, wagging its tail all the while, sniffed noses with each of the other pups, who were stretched out flat. The mother now trotted a mile to the east on some errand and returned a couple of hours later.

In the afternoon, some of the pups hunted mice. At 4 p. m. they all moved a mile out on the fiat and lay down. An hour later grandpa showed up, sniffed around where the wolves had been resting, and continued southward on their trail.

Family Moves 20 Miles From Polychrome.—The wolf family was seen at Polychrome Pass on September 22, 23, and 24. But on September 28 it had moved to a point on Teklanika River 20 miles away.

My attention was first attracted by the yellow pup which disappeared in a fringe of trees. Later I heard the howling of several wolves and saw the yellow pup trot in the direction of the sound and join the four black pups. Soon they all galloped out of sight. I advanced cautiously and came upon the five pups, their parents, and grandpa, 140 yards from me. I exposed some motion-picture film, then dropped out of view to change film. While I was thus occupied they all howled and there was considerable barking which resembled the yapping of coyotes. When I again peered over the rise all but the black male were moving away with much tail wagging and milling around. The black male saw me and trotted after the others, and all disappeared around the base of a low ridge. On my way back to the road I met the other four adults heading toward the spot where the wolves had howled. Apparently they had heard the noise too. The mantled male was quite surprised when he saw me 150 yards away and made several high jumps with head turned toward me. They all stopped to watch me, then slowly trotted on around the ridge after the others. This was about 9:30 a. m.; at 3 p. m. I found all the wolves resting near the base of a long slope about a mile away. They saw me approach in the distance and moved up the slope a short way from where they watched me. The following day I saw the band 4 miles to the north but I was unable to stalk them.

Figure 10: "Siesta."

The East Fork Family Still Together March 17.—Although tracks, presumably of the East Fork family, had been seen during the winter, the wolves had escaped observation. But on March 17 I came unexpectedly upon the band at Savage River, 30 miles from the East Fork den site. I followed several fresh tracks which crossed my way and led out on an open flat where there were many bare spots made by the caribou in pawing for grass and lichens. One of the many spots appeared a little different than the others so I looked at it through field glasses and saw that it was a black wolf stretched out on its side. Searching the flat ahead of me, I made out two more black wolves. Off to one side of these a gray wolf sat up and, before curling up, looked about at random, without noticing me as I crouched about 300 yards away. To reach a strip of woods from where I could watch the wolves unobserved, I back-tracked cautiously but was discovered just as I was about to enter the woods. The black wolf which saw me aroused all the others when it howled. At least 10 wolves came to life and after a brief view of me hurried away, kicking up sparkling puffs of snow as they galloped.

Dispersal of young.—I have little data on the dispersal of the young. The 1940 East Fork pups remained with the pack through the first winter until at least March 17, 1941, the last date I saw the pack together. On May 14 one of the pups was seen 2 miles from the den, and 3 days later another was seen at a similar distance from the old home. This was the last time I saw the 1940 pups. None of these young was ever seen at the 1941 den. Some of them may have been trapped during the winter, but at least three or four escaped the trappers.

EAST FORK RIVER DEN—1941

Same Pair Have Young at East Fork Den.—The East Fork den which was used in 1940 was again used in 1941. As in the previous season, the black male was mated to the gray female. On my first visit to the area on May 12 the black male was seen lying close to the den entrance. The mantled male headquartered at the den as he had done the previous year, but grandpa and the black-masked male were not seen all summer. Possibly they had been trapped during the winter. On June 21 four pups played on the bar and climbed over the father and the mantled male.

Black Female Has a Den.—The black female which helped the gray female take care of her young in 1940 was not seen at the old East Fork den early in the summer, but was several times noted in the region. On June 1 she and a large light-faced gray male that was with the band in the late summer of 1940 were traveling together on Igloo Creek. It was later learned that she was mated with this male, but her den was not found.

On June 30 two hikers saw the black female coming up East Fork River followed by a pup which, in crossing the river, was carried downstream some distance and treated a little roughly by the fast water. The hikers were able to run it down and catch it by the tail. They said that the mother barked at them from a point about 150 yards away. When they released the pup the mother continued up the river toward the den occupied by the gray female.

The following day I saw the black female coming down the bar but before I could take cover she had seen me. Instead of following down the bar she climbed a high ridge opposite me and then dropped down on the bar below me. I hoped she was on her way to her den, but if she were she changed her mind. After trotting down the bar one-third of a mile she climbed the bank, smelled about a knoll, then came back and climbed over a high ridge. I searched for her den, but did not find it. After reviewing the places where I had seen this wolf and tracks during the summer, it seemed certain that she had denned about 4 miles below the East Fork den occupied by the gray female.

On June 30 the black female and her pups were living at the den of her neighbor, the gray female. On July 9 the gray female and her mate had moved to a rendezvous a third of a mile above the den, where the pups spent much time in a clump of willows and the parents rested on the open bar nearby. On this day the black female was still using the gray female's den. On July 12 both families were together at the rendezvous. There were 10 pups—6 in one litter and 4 larger ones in the other. Gray and black pups were present in both litters.

The two families were living together at the rendezvous as late as August 3, the last day I visited the area. Besides the two pairs of adults there was one extra adult wolf at the rendezvous—the mantled male. In September a band of 15 wolves was seen about 3 miles from the den by a truck driver. These probably were the two families, still traveling together.

An incident in line with the observations on the East Fork wolves with respect to the association of two females is given by Seton (1929, vol. 1, p. 342) who writes as follows: "Thomas Simpson [1843, p. 275-76] while exploring the Arctic coast east of the Copper-mine, on July 25, 1838, encountered wolves at the mouth of a small stream near Hepburn Island, and thus refers to the incident: 'The banks of this river seemed quite a nest of wolves; and we pursued two females, followed by half a score of well-grown young. The mothers scampered up the highest rocks where they called loudly to their offspring; and the latter, unable to save themselves by flight, baffled our search by hiding themselves among the willows which fringe the stream. The leader of the whole gang a huge, ferocious old fellow—stood his ground, and was shot by McKay.'"

Behavior When Disturbed.—On the morning of July 9 I approached the wolf den with a companion and managed, without being discovered, to gain a clump of willows on the bank 100 yards south of the den and at about the same elevation. The black female was later seen a few yards above the den. I do not know that she was aware of our presence, but she trotted to the den and nimbly entered one of the three burrows. A little later a black pup emerged from some brush and waddled up to a burrow. In the afternoon the large gray mate of the black female came trotting down the den knoll. He sniffed at a pup, which then followed him. A moment after arriving at the burrows he suddenly became alert and looked intently toward us. Apparently he had heard the motion picture camera. He took a step forward and stood with muscles tense, peering searchingly at us. Then he loped up the slope out of view above us. The pups continued to move about near the den, unaware of any danger. The male soon appeared on the bar below us, about 200 yards away, and for several minutes howled and barked. While he howled at us the very tip of his tail twitched back and forth, as it does on a cat when it is waiting to pounce on a mouse. When he retreated we walked up the bar toward the rendezvous where we had seen the other pair with their pups. The male we had disturbed went ahead of us to this pair and as we neared them they all ran up the slope and out of sight. Several pups were seen and we found two of them in a clump of willows and spent some time trying to approach them for pictures, but they finally moved off and kept a respectable distance between us.