|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Fauna of the National Parks of the United States No. 6 The Bighorn of Death Valley |

|

PHOTOGRAPHS

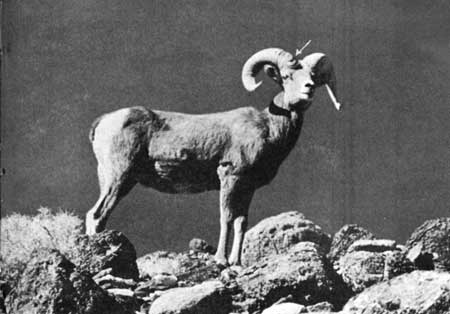

Figure 1.—This old ewe was the leader of the Badwater band. Her spreading horns, the right horn notched and crimped, and other distinguishing features of her companions, made possible the first uninterrupted month-long series of daily dawn-to-dark observations of a recognizable band of bighorn. This established the subsequent pattern of our research program. |

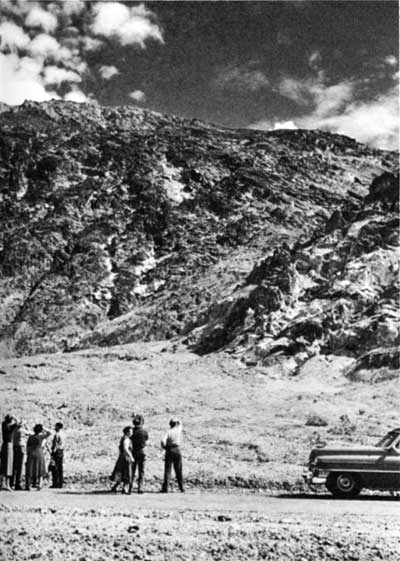

Figure 2.—We also carried on an extensive on-site interpretive program showing the bighorn to as many as 150 carloads of visitors per day during the band's 3-months overall use of the area. |

Figure 3.—At the end of each day we left the bighorn bedded down and moved whenever possible to higher elevations to escape the heat. Here, at 5,000 feet in the Cottonwood Mountains, the nights were comfortable for sleeping. |

Figure 4.—We returned to the lower elevations during the hot days where the only shade was what we made for ourselves. |

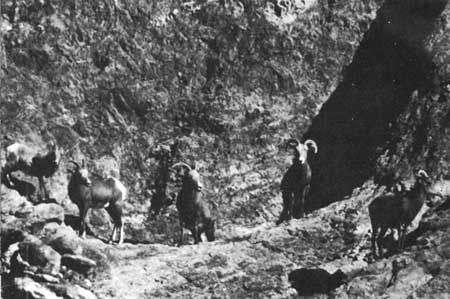

Figure 5.—After 4 days, the Badwater band climbed to a gravel- and water-filled basin, or tinaja, where the animals drank. The wide horns of the three adults on the right are a family characteristic. The uniquely down-curved horns of Droopy, the adult to right of center, are unmistakable; the Old Leader is left of center. |

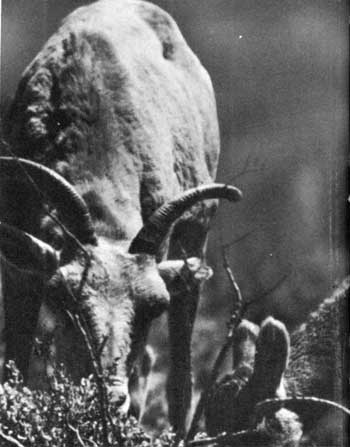

Figure 6.—Droopy reappeared 3 years later at Keystone Canyon 5 miles south of Badwater. Her unique set of horns underscores the fact that "hornprints" are as valuable as fingerprints in the identification of individuals. Each year of growth adds a new segment at the base of the horn. Droopy is 8 years old here. |

Figure 7.—The membership of bighorn bands does not remain constant, nor are the animals so gregarious that all are unhappy to be alone. For 38 days the Badwater band remained unchanged. But later it diminished from six to four, then one, as various individuals drifted away. The Old Leader seemed as contented alone as when leading the band. |

Figure 8.—At Willow Creek, in July 1955, the upper spring in the willows at right had not been used by bighorn for many years. In 1956 they beat trails through these willows and used the water at that place for one summer, but usually they prefer to water at more open spots further down the canyon. |

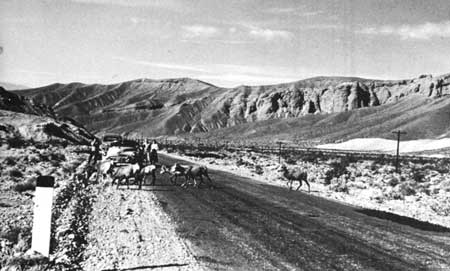

Figure 9.—Water flows intermittently down Willow Creek for 3 miles. Permanent water situated in rugged escape terrain has made this the home area for one of the region's largest concentrations of bighorn. |

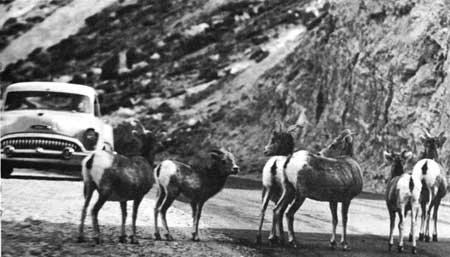

Figure 10.—On Paleomesa above Navel Spring, in December 1955, we watched a "band" form, first two, then five, seven, and finally eight. Their leader Old Mama (foreground), accepted us as a condition of the environment and fed closer as the days passed. |

Figure 11.—Within a few days Old Mama led the band down off the mesa into the Big Wash and bedded them on the mesa over a mile from any "cliffy terrain" hitherto supposed necessary to the sense of security of all bighorn at bedding time. |

Figure 12.—From Big Wash she led them on down to Deadman's Curve and back up Furnace Creek Wash. Bebbia juncea and Stephanomeria dominate both these washes, though not the mesa, and began immediately to assume a place of primary importance in the Death Valley bighorn diet. |

Figure 13.—By the 5th of January, 1956, Old Mama had not only induced the band to follow her across the highway, but they no longer paid any attention to the cars stopping and people pouring out to photograph them. |

Figure 14.—Finally on January 10, following Old Mama's example, the entire band stood stockstill in the middle of the highway, bringing all traffic to a halt. It should be emphasized that such tolerance with respect to humans is most unusual, and it developed in response to a unique leadership. |

Figure 15.—At Navel Spring the bighorn demonstrated that while they may not absolutely need water in the winter, they will make an 8-mile trip to get it. In winter they can go at least 3 weeks without water, but in summer they must drink every 3 to 5 days. Navel Spring is one of the key bighorn springs in Death Valley. |

Figure 16.—Although these bighorn would feed to within a year of us in the open wash at Navel Spring they suddenly found our presence to be an unacceptable condition in that environment. The old hunting blind overlooking Navel Spring probably has contributed to their increased anxiety at the spring. |

Figure 17.—At Navel Spring, Old Eighty (note "horn-print" and characteristic carriage of the head and graying muzzle) was photographed at 100 feet with a 500-mm lens. She reflects the tension of the entire band as she stares suspiciously down at us standing in the shadow of the box canyon below. |

Figure 18.—We had to retreat to a point 75 feet from the spring before they would let us observe their watering behavior. With much "spooking," they finally drained all the basins, but this was not enough water to satisfy their needs. Big Sandy paws in the mud and waits for her tracks to fill with water. |

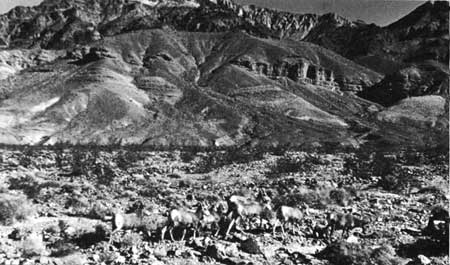

Figure 19.—However, not all of the band reacted to the confines of Navel Spring and our presence there in the same way. In open terrain Big Sandy was one of the wariest in the band, but her experience at the waterhole apparently had not included aggressive action from humans, and she was, surprisingly, less wary than even Old Mama. |

Figure 20.—The 6-month-old ram lamb played around too long and found nothing but mud when he came to drink at Navel Spring. Here he tries to make up his mind whether to go with the departing band or wait for more water to seep into their hoofprints. |

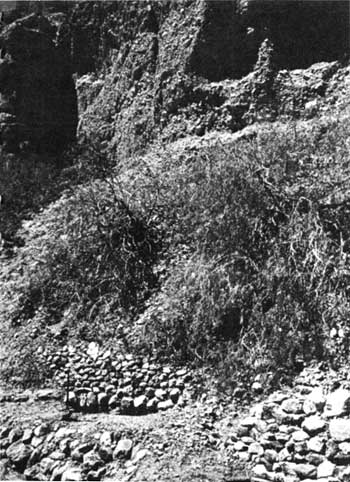

Figure 21.—Rehabilitation of Navel Spring consisted of digging back to the source of each trickle, then channeling it into one or more troughs made from half an oil drum, which we sank flush with the ground. Before the work, the seep shown here produced only 5 gallons per day. |

Figure 22.—Lowell Sumner came to our assistance on the water project and by the end of July 1956 we had made about 75 gallons of water available to the bighorn at Navel Spring, shown here, and had brought similar supplies to the surface at Virgin, Scotty's and Hole-in-the-Rock Springs. |

Figure 23.—We began to learn how specific or how transient the bands may be within the herd. During the autumn of 1956, Old Mama's band was in three small groups. These temporarily joined to become a record band of 18. Shown here are 15 of this group waiting for Old Mama and 2 others (not shown) to join them. |

Figure 24.—By the end of the summer, 1956, we had established our observation camp at Nevares Springs and had our first glimpse into the preliminary rituals of the rams. However, we saw no actual ram "fights" until the summer of 1957. |

Figure 25.—On August 27, 1957, our field identification study began to gain substance when Tight Curl arrived at Nevares Spring. We had known him in Furnace Creek Wash in November 1956 and in upper Echo Canyon in January 1957. His right horn curls much closer than his left, and both are badly marred at the frontal base by heavy fighting. |

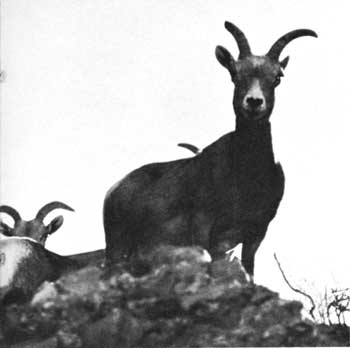

Figure 26.—Two types of identification. Tight Curl was "positive" because his distinguishing characteristics could scarcely be duplicated by another ram. But Little Whitey is a "relative" type. Her white rump and white face, which is relatively rare, coupled with a peculiar carriage of the head, make her identification "positive" only as long as she remains in the same area. |

Figure 27.—Some distinguishing characteristics may be temporary. The lump below the left ear of the Badwater lamb (Mischief), March 1955, was noticeable for 1 day only, then vanished. This is a "relative" type. |

Figure 28.—Old Mama, observed at Furnace Creek in 1956 and 1957, had a characteristic figure which could be recognized a mile away with a telescope. Her "horn-prints" were "positive," the right horn plate being chipped out at the base on the inside, which is very rare. Her right horn tip is broomed; her eyes, yellow. |

Figure 29.—The accident that gave Scarface her name could hardly be duplicated on another ewe. Once photographed for comparison, her identity could be established anywhere as "positive." |

Figure 30.—Rambunctious was present at Furnace Creek Wash in 1955 and 1956 and at Nevares Spring in 1957. The large scar on the right side, high up, of this 2-year-old-ram, as shown here, the smaller scar on the shoulder, and the pronounced annular sectioning of the horn-tips made identification fairly "positive." |

Figure 31.—Old Eighty has lost her right horntip. The ring near the middle of both horns, over a quarter of an inch deep, was unique. Whether this groove resulted from malnutrition during a bad year or from sickness is unknown. |

Figure 32.—Relative horn development is greater in a 6-month-old ram (Bad Boy, foreground) than in a ewe lamb (Little Whitey), left) of the same age. |

Figure 33.—Second and third from the left are the same ewe (Little Whitey) and ram (Bad Boy) at 18 months. The trend toward thicker, more outwardly-turned horns continues in the young ram. Animal at far left also is a young ram, the others are ewes. |

Figure 34.3When Old Mama returned with her newborn lamb on February 2, 1956, it could scarcely stand, wobbling precariously as it walked, falling down in the brush and rocks. Yet by 4 p.m. it had gained enough strength to climb out of the wash and followed its mother 1-1/2 miles up Pyramid Peak for bedding. |

Figure 35.—Within 10 days Old Mama's lamb was beginning to nibble at the same food its mother ate. The sparse and rigid character of the desert bighorn forage shown here is typical. |

Figure 36.—Having no other lambs to play with it played its own games, usually in the semidarkness of early dawn or late evening. It raced along the washes and leaped up cliffs that its mother usually climbed around. |

Figure 37.—When Old Mama's lamb was 6 weeks old, New Mama came into the wash with another lamb of the same age. |

Figure 38.—Old Mama's lamb went up to meet the new lamb at once, and they became inseparable companions. |

Figure 39.—Rough pelage among lambs (this is Old Mama's) is fairly common and is likely to be accompanied by a cough and lethargy. The unknown cause of these symptoms may be a contributing factor to lamb mortality. |

Figure 40.—Mesquite is a favorite thrashing post for rams during rut and serves in this respect as an introductory note to sign reading. A dismantled shrub, however, should not always be accepted as the sign of ram activity, because bighorn of all age classes and sexes may attack shrubs, especially during the spring shedding period. |

Figure 41.—This typical bighorn bed, 2 to 3 feet long, has been pawed in the loose soil of a rocky slope. This bed, on a slope in rough terrain, accompanied by a large number of pellets, probably is the night bed of an adult. Beds in open washes are likely to be day beds, for we have no record of night bedding there. |

Figure 42.—These three sizes of prints do not indicate three animals but probably two: A—four tracks of front feet; B—a hind foot of possibly the same animal; C—a smaller animal, probably a lamb. Since each animal leaves two sizes of prints it would take at least five sizes of prints to indicate three animals. |

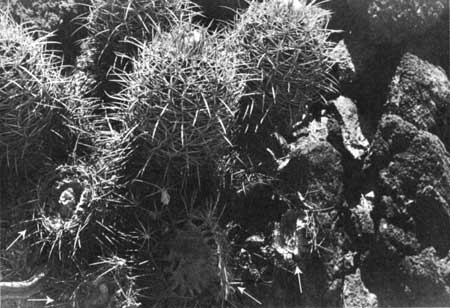

Figure 43.—A mature ram crushed these cottontop cactuses with the buldge of his horn, then pawed them open with a front foot. But this is our only observation in 8 years of the full use of his cactus by bighorn in Death Valley, indicating that generalizations from such single observations can lead to misconceptions of bighorn life history. |

Figure 44.—Small lambs can vanish quickly in the desert. We last saw this lamb (Little Fuzzy) alive on August 23, 1957. After we had searched for 3 days, we were led to its body in this advanced stage of decomposition by circling ravens and buzzards on August 30. Three months later, there were not even any bones left. |

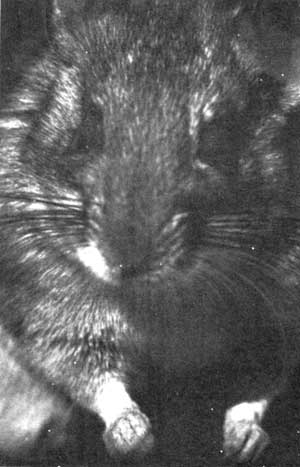

Figure 45.—Pack rats often confuse the beginner in sign reading by leaving pellets somewhat similar to lamb pellets and by "browsing" plants both for food and for nest-building. Additional confusion also can be caused by the browsing of chuckwallas. |

Figure 46.—Game trails are often reported to us as bighorn trails. On such trails the larger tracks usually are made by coyotes, and there is no sign of any of those on the valley floor being used by bighorn. But such tracks still give impetus among the credulous to the legend of the valley crossing by bighorn. |

Figure 47.—The rough gauntness of extremely dehydrated adults on their way to water is often mistaken for a generally poor condition. The same animals, fat and sleek from rehydration, can be mistakenly counted the second time as different animals. This astonishing transformation was observed many times. |

Figure 48.—A possible cause of mortality is suggested by the propensity of lambs to play on nearly sheer walls, leaping into the air and kicking their heels. This one lived to repeat the same antics the next evening until after dark, but we have found dead ones at the base of cliffs. |

Figure 49.—Forgotten Creek was rediscovered during this survey. It flows for nearly a mile down a canyon in the foothills of the Grapevines. We observed no sign of contemporary bighorn use, although old trails converged on the upper springs from the foothills. But sign quickly disappears in similar salty terrain at Nevares Spring as a result of chemical action. |

Figure 50.—The ecological undesirability of the feral burro in Death Valley is beyond question, but the actual extent of its threat to the bighorn has not been determined. The condition of Rest Spring shows that burros do not always foul springs. Bighorn will, if other conditions are acceptable, continue to water at springs utilized by burros. |

Figure 51.—This and following pictures are the only ones we have seen of desert bighorn on the jousting field. The tournament, which took place in an air temperature of 122° was between Broken Nose and Tabby, both between 10 and 12 years old. Bighorn sometimes mill around for hours "blowing," "growling," and "groaning," in the preliminary phase of the joust shown here. |

Figure 52.—The ritual includes and elaborate pretense of disinterest in which one ram turns away and pretends to eat or polish his horns in a nearby shrub. But their eyes are set out so far that they see behind them and know what the other is doing. We have never seen one attempt to "blast" the other during this preliminary maneuver. |

Figure 53.—Occasionally they both rear instantaneously from this position and lunge at close range. Usually, however, they turn their backs with every indication of indifference and walk away. But here again each is watching every move of the other, and at varying distances some communication known only to them signals the next move. |

Figure 54.—Having walked away a certain number of paces, suddenly they whirl and rise to their hindlegs, then "sighting down their noses" they race toward each other in an upright position, gaining speed and leaning farther forward as they approach. |

Figure 55.—When they are about 12 feet apart, with every muscle bulging for a final effort, and with amazing timing and accuracy, they lunge forward like football tacklers. |

Figure 56.—Their combined speed at impact has been estimated at 50 to 70 miles per hour and to be the equivalent of a 2,400-pound blow. We counted over 40 such blows between two other rams in one afternoon. |

Figure 57.—The remarkable synchronization of movement pictured here is the rule, not the exception. Every effort seems to be made to insure a perfect head-on and balanced contact. Note that both heads are tilted to the same side. |

Figure 58.—Sometimes the heads are tilted in opposite directions, resulting in a blow on the forehead itself instead of on the horns, but the encounter is still head-on and in balance. |

Figure 59.—Occasionally one slips or miscalculates and a severe neck-twisting or nose-smashing can result. Tabby, the ram on the left, has a scar on the right side. Broken Nose has a dark patch on the left horn. Tabby has not watered for 3 days, and shows the gauntness and rough coat of dehydration. |

Figure 60.—This 7-year-old ewe was captured and brought to the Desert Game Range in 1947 when she was a lamb. Here 6-week-old lamb was born in 1954 and registered in the Desert Game Range genealogy as "female No. 7." |

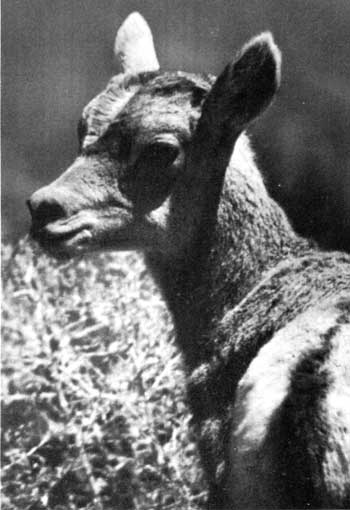

Figure 61.—This is "female No. 7," when 6 weeks old in April 1954. At this age, the previously ill-defined rump patch turns white. The horns have not appeared, but the characteristic tufts of hair often are mistaken for beginning horns. |

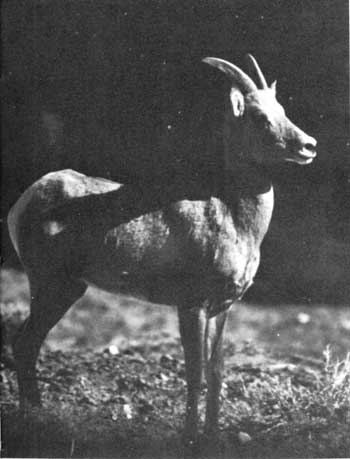

Figure 62.—"Female No. 7," when 7 months old in October 1954. |

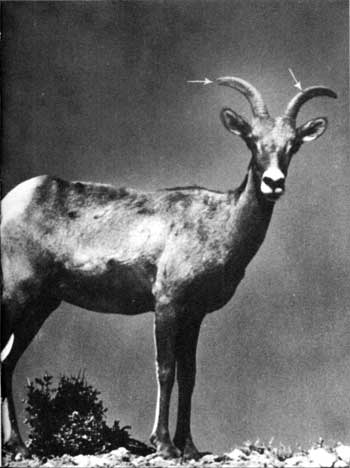

Figure 63.—"Female No. 7," when 2 years and 7 months old in October 1956, accompanied by her 6-1/2-month-old ewe lamb, which was born on April 4, 1956. These relatively inconspicuous "extra" growth rings appear fairly often in ewes. |

Figure 64.—"Female No. 7," when 2 years and 7 months old in October 1956. |

Figure 65.—"Female No. 7's" ewe lamb in September 1957 at the age of 17-1/2 months. She has the relatively slender body, low withers, and high horns of her mother. (See fig. 66.) |

Figure 66.—"Female No. 7," at 3 years and 7 months in October 1957. Notch at tip of right horn would be another useful characteristic in field identification. Small dark spot on left horn shows here and also in figures 63 and 67, permitting positive location of horn growth stages. |

Figure 67.—"Female No. 7," at 3 years and 7 months (right), here 17-1/2-month-old ewe lamb (left), and her 4-month-old ram lamb (center), showing relative sizes and horn development. |

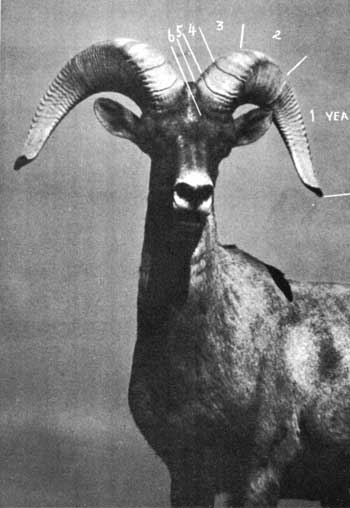

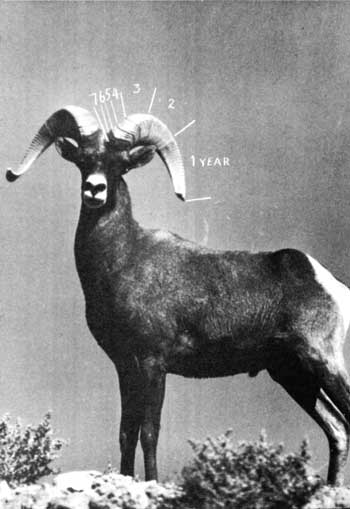

Figure 68.—The following pictures show the growth and development of the Old Man, captured as a lamb in the late summer of 1948 and kept in a large fenced inclosure at the Desert Game Range where he was photographed by us annually from 1953 to the date of this writing. March 1953. Age: 5 years. |

Figure 69.—February 1954. Age: 6 years. |

Figure 70.—January 1955. Age: 7 years. |

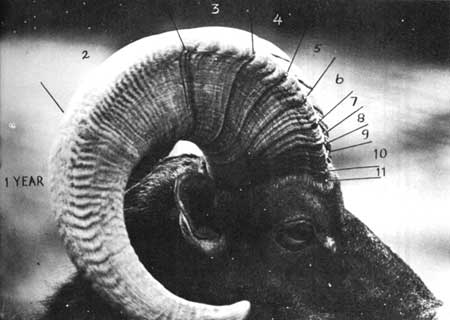

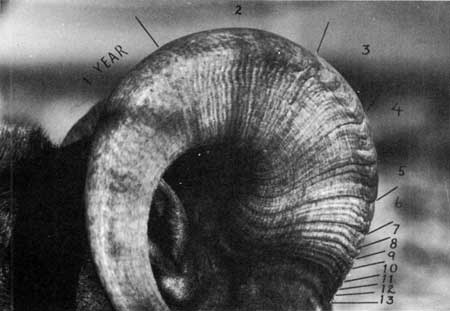

Figure 71.—January 1957. Age: 9 years. |

Figure 72.—August 1958. Age: 10 years. |

Figure 73.—July 1959. Age: 11 years. |

Figure 74.—April 1960. Age: 12 years. |

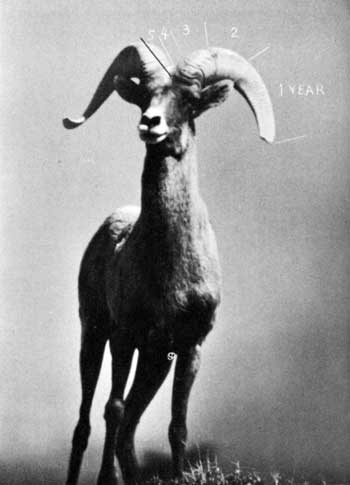

Figure 75.—January 1961. Age 1 years. Note that beginning in 1957 at 9 years, no new light-colored annual rings has matured, so that now in 1961 the dark "ring" at the base of the horn is actually composed of five narrow dark rings, each indicating a year's growth. This is typical of desert bighorn ram development. |

Figure 76.—As we left in 1961, the Old Man followed along the fence, bleating. We were reminded that he was 13 years old and that his teeth were going now and that when we came another year things might not be the same. For things will not be the same there again—when the Old Man is gone. |

Figure 77.—Predictions were made in 1937 that wild burros would drive the bighorn away from Lost Spring. But the 1960 observations of the authors, and this 1961 photograph by Park Naturalist Ro Wauer, indicate that bighorn and burros have shared this water without apparent friction for a quarter of a century. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

fauna/6/photos.htm

Last Updated: 01-Feb-2016