|

Popular Study Series History No. 6: New Echota, Birthplace of the American Indian Press |

|

New Echota Birthplace of the

American Indian Press*

By Hugh R. Awtrey, Associate Recreational Planner, National Park Service.

NEW Echota Marker National Memorial is one of the smallest and most obscure of the 162-areas administered by the National Park Service. Few travelers turn aside from the Dixie Highway (U. S. Route No. 41) onto the rural road that leads from the present town of Calhoun to a pastoral scene in the north Georgia hills where a modest stone chronicles briefly the rise and fall of a nation. The story seldom is told, yet merits constant and eloquent repetition; for it is the recital of an unparalleled human achievement. It is the record of a people raised in a scant decade, by its own intellectual bootstraps, from unlettered savagery to the refined estate of a government by published code—and a literature by the printed word. It is the moving but tragic history of the Cherokee Indians.

SEQUOYAH (From a pencil drawing by Samuel O. Smart based on reproduction of the original portrait). |

American ethnologists, political economists, social and religious historians, and students in numerous allied fields may find at this abandoned eastern capital of the Cherokees the subjects for fruitful investigation into many questions of aboriginal culture. The present discussion is intended merely to suggest some of the little-trod trails of inquiry which might lead to profitable discoveries in the realm of Indian journalism, a surprisingly prolific institution which had its origins 112 years ago at New Echota before it spread westward and gave the first periodical press to at least two of the young States beyond the Mississippi.1

New Echota's unique page in the history of world journalism is an incidental gift of Sequoyah, that incredible genius whose career still awaits a comprehensive biography which overreaches academic quibble. Long recognized as "America's Cadmus," that untutored linguist, who spoke no word of English or any other "civilized" tongue, endowed his fellow tribesmen with a written language which offered to the eye an easy and faithful transcript of their ancient speech.

Strange to tell, Sequoyah, hero of his nation, beneficiary of the only literary pension ever granted by the United States Government, recipient of a medal from Congress, commemoratee in Statuary Hall at the National Capitol, official emissary in Washington, veteran of the War of 1812, subject of an oil portrait by a leading painter of the day, drunkard turned prohibitionist, artisan who developed silvercraft to the highest point attained by North American Indians, inspiration for the name of a famous giant tree, and, above all, inventor of a remarkably efficient system of language signs, remains today, a century after his death, something of a man of mystery.2

This fact becomes all the more astounding when it is considered that many inquiring visitors, including men of literary reputation, interviewed Sequoyah in his later years. Nevertheless, his paternity, the time and place of his birth, and even the details of his death are unproved questions which have tantalized numerous researchers. One of them,3 after a cautious review of the evidence, believes that "it may be enough to say that Sequoyah was born of a Cherokee mother, somewhere in the lower Appalachian region, between the years 1755 and 1775."

Fortunately for those lay readers who are not disagreeably insistent upon microscopic substantiation of pleasantly plausible theories, most students of the Sequoyan saga concede, with varying degrees of reservation, that the gifted Indian was born about 1760 at Fort Loudon, near the original Echota in east Tennessee, the son of a white man.4 The somewhat uninspiring etymological thesis has been advanced that the hero's name is derived from Sikwa, suggesting "pig pen."5 Another explanation, which perhaps could not withstand the dissolving acids of philological scrutiny, is that the Indian mother, forsaken by her itinerant spouse before the arrival of their child, chose the name Sequoia, meaning "he guessed it."6 Happily, such discussions are but academic bypaths which stem from the high road of achievement blazed by the man himself.

(click on the image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Divested of split-hair carpisms, the essential story starts with Sequoyah's recognition of the superior power that written speech, "talk on paper," conferred upon the men who understood it, in contradistinction to those who could transmit their ideas only by mouth. He began in 1809 to devise a system of symbols for words and ideas which developed gradually into an elaborate, laborious, and inflexible pictography similar in basic principle to Chinese. Aware of his error, he made a new start; and there was his stroke of genius. He noted carefully every sound in the Cherokee language and designated each by an arbitrary character.7 After a decade of experimentation, while enduring patiently the jeers of relatives and friends, he perfected a system of 85 fundamental symbols, plus one recurrent prefix, and evolved, not precisely an alphabet, but a syllabary—a phonetic transcription of the entire Cherokee vocabulary with its bewildering 9 modes, 15 tenses, and 3 numbers (singular, dual, and plural).

The prime significance of Sequoyah's invention, however, was not his own mastery of a complex lingual problem. It was the amazing facility with which others could learn the system. A considerable number of the Cherokee Indians, some of them cultured and wealthy, commanded polished English, and a few perhaps were scornful of the syllabary. The unschooled tribesmen, however, found it a linguistic open sesame which unfolded magnificent new vistas of knowledge and vicarious experience. Scoffers were quieted by a successful public demonstration of the system in 1821, and thousands of Indians were conversant with it by the following year.8 It was adopted officially in 1825 by the general council of the Cherokee Nation.9

Stirrings of powerful new intellectual interests among the Indians soon were observed by workers at Brainerd Mission, an institution near the present city of Chattanooga, which had been established in 1817 by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.10 The Missionary Herald of February 1826, reported:

A form of alphabetical writing, invented by a Cherokee named George Guess, who does not speak English, and was never taught to read English books, is attracting great notice among the people generally. The interest in this matter has been increasing for the last 2 years; till, at length, young Cherokees travel a great distance to be instructed. . . . In 3 days they are able to commence letter writing, and return home to their native villages prepared to teach others. . . . Probably at least 20, perhaps 50, times as many would read a book printed with Guyst's character, as would read one printed with the English alphabet.11

Dr. Samuel A. Worcester, a distinguished New England missionary who lived among the Cherokees for 34 years and served for a time as New Echota's postmaster, seized upon the Seyuoyan syllabary as a potent instrument for the diffusion of religious literature. He urged the immediate establishment of a press which would disseminate, by the new-found system, the message that he had sought to convey through the clumsy device of interpreted sermons and lectures. The Board of Commissioners had received an urgent plea as early as September 1825:

The Cherokees have for some time been very desirous to have a press of their own, that a newspaper may be published in their own language. . . . Already the four Gospels are translated and fairly copied; and if types and a press were ready, they could be immediately revised and printed and read.12

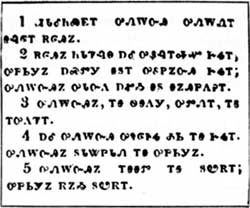

The Missionary Herald of December 1827,13 contains several items of superlative significance in Cherokee history. One is the eleven-line reproduction (see illustration) of Dr. Worcester's translation of the first five verses of Genesis—the initial use, in printed form, of Sequoyah's phonetic symbols. Another is the announcement that a font of Cherokee type had been cast in Boston and "an iron press of improved construction" purchased. Reflecting the missionary group's interest in the venture, the note continues:

A Prospectus has also been issued for a newspaper, entitled the Cherokee Phoenix, to be printed partly in Cherokee and partly in English. . . . All this had been done by order of the Cherokee Government, and at their expense. . . .14

Among the Cherokees, then, we are to see the first printing press ever owned and employed by any nation of the Aborigines of this Continent, the first effort at writing and printing in characters of their own; the first newspaper, and the first book printed among themselves; the first editor; and, the first well-organized system for securing a general diffusion of knowledge among the people. Among the Cherokees, also, we see established the first regularly elective government, with the legislative, judicial, and elective branches distinct; with the safeguards of a written Constitution and a trial by jury. . . .

When the first five verses of the Book of Genesis appeared in this translated form in The Missionary Herald of December 1827, it marked the first composition printed in the Sequoyan syllabary. |

The Cherokee press and type were shipped by water from Boston in November 1827. They arrived at Augusta, Ga., via Savannah, and finally reached New Echota in January 1828, after an overland trip by wagon. Isaac H. Harris and John F. Wheeler, two printers who had waited at the Cherokee capital since December 23, 1827, greeted the equipment with professional enthusiasm. Wheeler, who went to Arkansas in 1834 and became a pioneer typographer in the new country of the West, designed the first Cherokee type case, probably while at New Echota, but never received a patent for it.15 He later recalled the arrival of the printing materials in north Georgia:

The Press, a small royal size, was like none I ever saw before or since. It was cast iron, with spiral springs to hold up the plates, at that time a new invention. We had to use balls of deerskin stuffed with wool for inking, as it was before the invention of the composition roller. . . . John Candy, a native half-breed . . . could speak the Cherokee language, and was of great help to me in giving me the words where they were not plainly written.16

The absence of newsprint caused a delay in the publication of Volume I, No. 1, of Tsalagi-twi-le-hi sani-hi, the Cherokee Phoenix. A supply finally was obtained from Tennessee and, on February 21, 1828, there appeared the inaugural issue of the father of America's aboriginal newspapers. It was a journal of four five-columned pages measuring 21 by 14 inches. The vignette included a representation of the fabulous phoenix, the Egyptian bird which lived for 500 years, was consumed by a cleansing fire, and arose from its own ashes in all its youthful freshness. That first issue announced that the weekly Phoenix could be procured for 42.50 a year paid in advance, or $3.50 paid at the end of the year. Rates were reduced to $2 and $2.50 for non-English readers. Altogether, the paper justified the 1827 prospectus, already mentioned, which had said that it would contain:

(1) The laws and published documents of the Nation.

(2) Accounts of the manners and customs of the Cherokees, and their progress in education, religion, and the arts of civilized life, with such notices of other Indian tribes as our limited means of information will allow.

(3) The principal interesting news of the day.

(4) Miscellaneous articles, calculated to promote literature, civilization, and religion among the Cherokees.17

Here an admirable and tragic character appears on the journalistic stage of the American Indians. He is Elias Boudinott, known also as Kub-le-ga-nah (and other spellings), meaning "The Buck," a brilliant young part-breed who had been singled out at Brainerd Mission and sent to a higher church school at Cornwall, Conn. Among his scholarly achievements at an early age was the distinction of having calculated a solar eclipse, "very neatly projected and the results stated in the usual form."18 Boudinott, whose signature bore two "t's," although he had adopted the name of Elias Boudinot, Governor of New Jersey and President of the American Bible Society,19 created something of a social ferment when he married Harriet Ruggles Gold20 at Cornwall in 1822 and departed with his white bride for the wilderness of New Echota. Because of his superior mental powers and his excellent training, he was chosen clerk of the Cherokee National Council. With the issuance of the Phoenix he became America's first Indian editor.

Aware of the extraordinary handicaps imposed upon him by a pioneer publishing venture born in the wilds of Cherokee Georgia, young Boudinott was diplomatic but purposeful as he wrote his first editorial. The newspaper was not undertaken for profit, he explained, but would depend largely on the liberality of his supporters. He continued:

We would now commit our feeble efforts to the good will and indulgence of the public . . . hoping for that happy period when all the Indian tribes of America shall arise, Phoenix-like, from the ashes, and when the terms "Indian depredation," "war-whoop," "scalping-knife," and the like, shall become obsolete, and forever be buried "deep underground."

*From The Regional Review (National Park Service, Region One, Richmond, Va.), Vol. IV, No. 3, March 1940, pp. 24-35.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Oct 20 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |