|

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park |

|

PART ONE

THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER, 1862

(continued)

Seven Pines (Fair Oaks)

Slowed by the heavy rains and the bad condition of the roads, where "teams cannot haul over half a load, and often empty wagons are stalled," McClellan finally established his base of supply at White House on May 15. Five days later his advance crossed the Chickahominy River at Bottoms Bridge. By the 24th the five Federal corps were established on a front partly encircling Richmond on the north and east, and less than 6 miles away. Three corps lined the north bank of the Chickahominy, while the two corps under Generals E. D. Keyes and Samuel P. Heintzelman were south of the river, astride the York River Railroad and the roads down the peninsula.

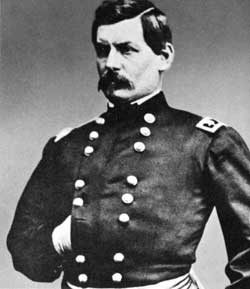

Gen. George B. McClellan Courtesy, Library of Congress. |

With his army thus split by the Chickahominy, McClellan realized his position was precarious, but his orders were explicit: "General McDowell has been ordered to march upon Richmond by the shortest route. He is ordered * * * so to operate as to place his left wing in communication with your right wing, and you are instructed to cooperate, by extending your right wing to the north of Richmond * * *"

Then, because of Gen. Thomas J. ("Stonewall") Jackson's brilliant operations in the Shenandoah Valley threatening Washington, Lincoln telegraphed McClellan on May 24: "I have been compelled to suspend McDowell's movements to join you." McDowell wrote disgustedly: "If the enemy can succeed so readily in disconcerting all our plans by alarming us first at one point then at another, he will paralyze a large force with a very small one." That is exactly what Jackson succeeded in doing. This fear for the safety of Washington—the skeleton that haunted Lincoln's closet—was the dominating factor in the military planning in the east throughout the war.

Lincoln's order only suspended McDowell's instructions to join McClellan; it did not revoke them. McClellan was still obliged to keep his right wing across the swollen Chickahominy.

Learning of McDowell's withdrawal, Johnston decided to attack the two Federal corps south of the river, drive them back and destroy the Richmond and York River Railroad to White House. Early in the morning on May 31, after a violet rainstorm that threatened to wash all the Federal bridges into the river, Johnston fell upon Keyes and Heintzelman with 23 of his 27 brigades at Seven Pines.

McClellan's troops repairing Grapevine Bridge.

Courtesy,

Library of Congress.

The initial attack was sudden and vicious. Confederate Gen. James Longstreet threw Gen. D. H. Hill's troops against Gen. Silas Casey's division of Keyes' corps, stationed about three-quarters of a mile west of Seven Pines. Longstreet overwhelmed the Federal division, forcing Casey to retreat a mile east of Seven Pines. Keyes then put Gen. D. N. Couch's division on a line from Seven Pines to Fair Oaks, with Gen. Philip Kearney's division on his left flank. Not until 4 that afternoon, however, did Confederate Gen. G. W. Smith send Whiting's division against Couch's right flank at Fair Oaks. The delay was fatal. Although Couch was forced back slowly, he drew up a new line of battle facing south towards Fair Oaks, with his back to the Chickahominy River. Here he held until Gen. Edwin V. Sumner, by heroic effort, succeeded in getting Gen. John Sedgwick's division and part of Gen. I. B. Richardson's across the tottering Grapevine Bridge to support him. Led by Sumner himself, Sedgwick's troops repulsed Smith's attack and drove the Confederates back with heavy losses.

The battle plan had been sound, but the attack was badly bungled. Directed by vague, verbal orders instead of explicit, written ones, whole brigades got lost, took the wrong roads, and generally got in each other's way. Nine of the 23 attacking brigades never actually got into the fight at all. Towards nightfall Johnston was severely wounded in the chest and borne from the field. The command then fell to G. W. Smith. Fighting ceased with darkness.

Early next morning, June 1, Smith renewed the attack. His plan called for Whiting on the left flank to hold defensively, while Longstreet on the right swung counterclockwise in a pivot movement to hit Richardson's division, which was facing south with its right near Fair Oaks. The Federal troops repulsed the assault, however, and when Heintzelman sent Gen. Joseph Hooker's division on the Federal left on the offensive, the Confederates withdrew and the battle was over before noon.

That afternoon President Jefferson Davis appointed his chief military advisor, Gen. Robert E. Lee, as commander of the Southern forces. Lee promptly named his new command the Army of Northern Virginia—a name destined for fame in the annals of the Civil War.

Although the battle itself was indecisive, the casualties were heavy on both sides. The Confederates lost 6,184 in killed, wounded, and missing; the Federals, 5,031. Undoubtedly the most important result of the fight was the wounding of Johnston and the resultant appointment of Lee as field commander.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |