|

RICHMOND National Battlefield Park |

|

PART ONE

THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN, SUMMER, 1862

(continued)

Lee's fortifications east of Mechanicsville Turnpike.

From a contemporary sketch.

Lee Takes Command

Lee immediately began to reorganize the demoralized Southern forces and put them to work digging the elaborate system of entrenchments that would eventually encircle Richmond completely. For this the troops derisively named him the "King of Spades." But Lee was planning more than a static defense. When the time came these fortifications could be held by a relatively small number of troops, while he massed the bulk of his forces for a counteroffensive. He was familiar with and believed in Napoleon's maxim: "* * * to manoeuver incessantly, without submitting to be driven back on the capital which it is meant to defend * * * "

On June 12 Lee sent his cavalry commander, Gen. J. E. B. ("Jeb") Stuart, with 1,200 men, to reconnoiter McClellan's right flank north of the Chickahominy, and to learn the strength of his line of communication and supply to White House. Stuart obtained the information, but instead of retiring from White House the way he had gone, he rode around the Union army and returned to Richmond on June 15 by way of the James River, losing only one man in the process.

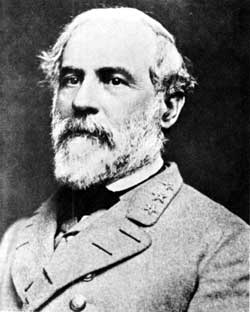

Gen. Robert E. Lee. Courtesy, National Archives. |

It was a bold feat, and Stuart assured his chief that there was nothing to prevent his turning the Federal right flank. But the daring ride probably helped McClellan more than Lee. Alerted to the exposed position of his right flank and base of supply, McClellan withdrew his whole army south of the Chickahominy, with the exception of Gen. Fitz-John Porter's corps, which stretched from Grapevine Bridge to the Meadow Bridge west of Mechanicsville. On June 18 he started the transfer of his enormous accumulation of supplies with the shipment of 800,000 rations from White House to Harrison's Landing on the James River. After Jackson's success in the Shenandoah Valley at Cross Keys and Port Republic, it was becoming apparent even to McClellan that McDowell probably never would join him, in which case he wanted his base of operations to be the James rather than the York River.

Meanwhile, pressure from Washington for an offensive movement against Richmond was mounting. But because of the wettest June in anyone's memory, McClellan was having trouble bringing up his heavy siege guns, corduroying roads, and throwing bridges across the flooded Chickahominy swamps. As one bedraggled soldier wrote: "It would have pleased us much to have seen those 'On-to-Richmond' people put over a 5 mile course in the Virginia mud, loaded with a 40-pound knapsack, 60 rounds of cartridges, and haversacks filled with 4 days rations."

Also, McClellan believed erroneously that the Confederates had twice as many available troops as he had. Consequently, his plan of action, as he wrote his wife, was to "make the first battle mainly an artillery combat. As soon as I gain possession of the 'Old Tavern' I will push them in upon Richmond and behind their works; then I will bring up my heavy guns, shell the city, and carry it by assault."

Chickahominy swamps.

Courtesy, National Archives.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |