|

WRIGHT BROTHERS National Memorial |

|

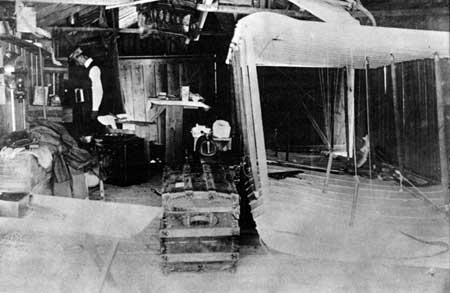

Wilbur Wright in Kill Devil Hills camp building before it was

remodeled by adding space for living quarters, Aug. 29, 1902. (1901

glider at right.)

Glider Experiments, 1902

The Wrights had faith in the tables of air pressure compiled from their wind-tunnel experiments. Their new knowledge was incorporated into a larger glider which they built based on the aerodynamic data they had gained. Now they wanted to verify those findings by actual gliding experiments. At the end of August 1902, they were back in camp at Kill Devil Hills for the third season of experiments. Battered by winter gales, their camp needed repairing. They decided to build a 15-foot addition to the combined workshop and glider-storage shed to use as a kitchen and living quarters. Their new living quarters were "royal luxuries" when compared with the tent facilities of previous camps.

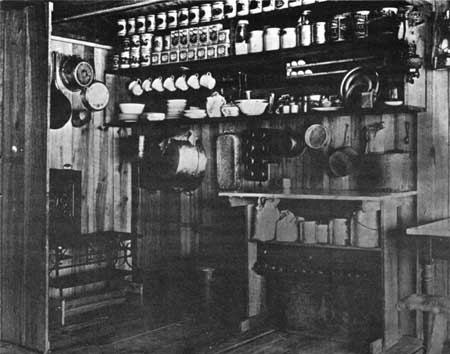

Kitchen in the living quarters of the remodeled camp building at Kill

Devil Hills, 1902.

The new glider had a wingspan of 32 feet, 1 inch; a considerable increase over the wingspan of 22 feet for the 1901 glider. Its lifting area, 305 square feet, was not much greater than the glider of the previous year. Their wind-tunnel experiments having demonstrated the importance of aspect ratio, the brothers made the wing span about six times the chord or fore-and-aft measurement instead of three. Weighing 112 pounds, the glider was 16 feet, 1 inch long. In the 1900 and 1901 gliders, the wing-warping mechanism had been worked by movement of the operator's feet. In the 1902 glider this mechanism operated by sidewise movement of the operator's hips resting in a cradle on the lower wing. Wilbur wrote his father from camp, "Our new machine is a very great improvement over anything we had built before and over anything any one has built."

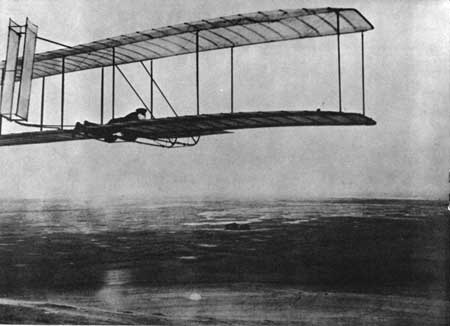

One of the successful glides made in October 1902 with the 1902

glider, camp buildings in distance.

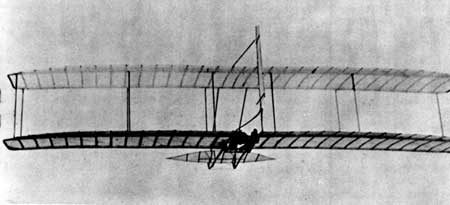

Wilbur Wright making right run in glide from West Hill, Oct. 24,

1902. (Kill Devil Hill in background.)

This was the first Wright glider to have a tail, consisting of fixed twin vertical vanes, as well as a front rudder. The tail's purpose was to overcome the turning difficulties encountered in some of the flights with the 1901 glider by maintaining equal speeds at the two wingtips when the wings were warped. The tail was expected to counterbalance the difference in resistance of the two wingtips. If the wing on one side tended to swerve forward, then the Wrights thought the tail, being more exposed to the wind on the same side, should stop the glider from turning farther.

The tail on this glider, however, caused a new problem that had not occurred in their previous gliders. At times, when struck by a side gust of wind, the glider turned up sidewise and came sliding laterally to the ground in spite of the effort and skill of the operator in using the warping mechanism to control it. The brothers were experiencing tailspins, though that term did not come into use until several years later. When tailspins occurred, the glider would sometimes slide so fast that the movement caused the tail's fixed vertical vanes to aggravate the turning movement instead of counteracting it by maintaining an equal speed at the opposite wingtips. The result was worse than if there were no fixed vertical tail.

While lying awake one night, Orville thought of converting their vertical tail from two fixed vanes to a single movable rudder. When making a turn or recovering lateral balance, this rudder could be moved toward the low wing to compensate for the increased drag imparted to the high wing by its greater angle of attack. Wilbur listened attentively when Orville told him about the idea the next morning. Then, without hesitation, Wilbur not only agreed to the change but immediately proposed the further important modification of interconnecting the rudder control wires with those of the wing-warping. Thus by a single movement the operator could effect both controls. Through the brilliant interplay of two inventive minds, all the essentials of the Wright control system were completed within a few hours.

The combination of warp and rudder control became the key to successful control of their powered machine and to the control of all aircraft since. (Modern airplanes—and indeed Wright planes after the middle of their 1905 experimental season—do not have the aileron and rudder controls permanently interconnected, but these controls can be and are operated in combination when necessary.) Together with the use of the forward elevator, it allowed the Wrights to perform all the basic aerial maneuvers that were necessary for controlled flight. The essential problem of how to control a flying machine about all three axes was now solved.

High glide on Oct. 10, 1902.

Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution.

The trials of the 1902 glider were successful beyond expectation. Nearly 1,000 glider flights were made by the Wrights from Kill Devil, West, and Little Hills. A number of their glides were of more than 600 feet, and a few of them were against a 36-mile-an-hour wind. Flying in winds so strong required great skill on the part of the operator. No previous experimenter had ever dared to try gliding in so stiff a wind. Orville wrote his sister, "We now hold all the records! The largest machine we handled in any kind [of weather, made the longest dis]tance glide (American), the longest time in the air, the smallest angle of descent, and the highest wind!!!" Their record glide for distance was 622-1/2 feet in 26 seconds. Their record glide for angle was an angle of 5° for a glide of 156 feet. The 1902 glider had about twice the dynamic efficiency of any other glider ever built up to that time anywhere in the world.

By the end of the 1902 season of experiments, the Wrights had solved two of the major problems: how properly to design wings and control surfaces and how to control a flying machine about its three axes. Most of the battle was now won. There remained only the major problem of adding the engine and propellers. Before leaving camp, the brothers began designing a new and still larger machine to be powered with a motor.

It was the 1902 glider that the Wrights pictured and described in the drawings and specifications of their patent, which they applied for in March of the following year. Their patent was established, through the action of the courts in the United States and abroad, as the basic or pioneer airplane patent.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |