|

WRIGHT BROTHERS National Memorial |

|

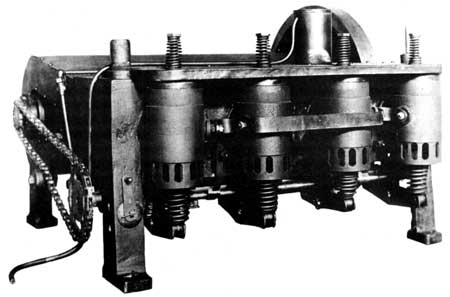

The Wright motor used in the first flights of Dec. 17, 1903, after

its reconstruction in 1928.

The Motor and the Propellers

Home again in Dayton, the Wrights were ready to carry out plans begun in camp at Kill Devil Hills for a powered machine. They invited bids for a gasoline engine which would develop 8 to 9 horsepower, weigh no more than 180 pounds or an average of 20 pounds per horsepower, and be free of vibrations. None of the manufacturers to whom they wrote was able to supply them with a motor light enough to meet these specifications. The Wrights therefore designed and built their own motor, with their mechanic, Charles E. Taylor, giving them enthusiastic help in the construction.

The engine body and frame of the first "little gas motor" which they began building in December 1902 broke while being tested. Rebuilding the light-weight motor, they shop-tested it in May 1903. In its final form the motor used in the first powered flights had 4 horizontal cylinders of 4-inch bore and 4-inch stroke, with an aluminum-alloy crankcase and water jacket. The fuel tank had a capacity of four-tenths of a gallon of gasoline. The entire power plant including the engine, magneto, radiator, tank, water, fuel, tubing, and accessories weighed a little more than 200 pounds.

Owing to certain peculiarities of design, after several minutes' run the engine speed dropped to less than 75 percent of what it was on cranking the motor. The highest engine speed measured developed 15.76 horsepower at 1,200 revolutions per minute in the first 15 seconds after starting the cold motor. After several minutes' run the number of revolutions dropped rapidly to 1,090 per minute, developing 11.81 brake horsepower. Even so, the Wrights were pleasantly surprised since they had not counted on more than 8 horsepower capable of driving a machine weighing only about 625 pounds. Having a motor with a power output of about 12 horsepower instead of 8, the Wrights could build the machine to have a larger total weight than 625 pounds.

The motor was started with the aid of a dry-battery coil box. After starting, ignition was provided by a low-tension magneto, friction-driven by the flywheel. No pump was used in the cooling system. The vertical sheet-steel radiator was attached to the central forward upright of the machine.

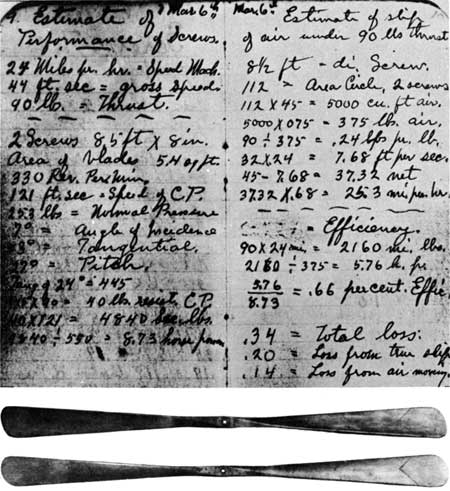

Propeller estimates, made by the Wrights 8 months before

the flights of December 1903. Their formulas resulted in the highly

efficient propellers which were used in the first Wright Flyer.

These were 8-1/2 feet from one canvas-covered tip to the other.

Top view shows the front, bottom view, the rear.

When the brothers began to consider designing propellers, they unhappily discovered that the forces in action on aerial propellers had never been correctly resolved or defined. Since they did not have sufficient time or funds to develop an efficient propeller by the more costly trial-and-error means, it was necessary for them to study the screw propeller from a theoretical standpoint. By studying the problem, they hoped to develop a theory from which to design the propellers for the powered machine. The problem was not easy, as the Wrights wrote:

What at first seemed a simple problem became more complex the longer we studied it. With the machine moving forward, the air flying backward, the propellers turning sidewise, and nothing standing still, it seemed impossible to find a starting point from which to trace the various simultaneous reactions. Contemplation of it was confusing. After long arguments we often found ourselves in the ludicrous position of each having been converted to the other's side, with no more agreement than when the discussion began.

However, in a few months the brothers untangled the conflicting factors and calculations. After studying the problem, they felt sure of their ability to design propellers of exactly the right diameter, pitch, and area for their need. Estimates derived from their formulas led to their propellers operating at a higher rate of efficiency (66 percent) than any others of that day. The tremendous expenditure of power that characterized experiments of other aeronautical investigators up to that time were due to inefficient propellers as well as inefficient lifting surfaces.

The Wright propellers, designed according to their own calculations, were the first propellers ever built by anyone for which the performance could be predicted. After tests, their propellers produced not quite 1 percent less thrust than they had calculated. In useful work they gave about two thirds of the power expended—a third more than had been achieved by such men as Sir Hiram Maxim and Dr. Langley.

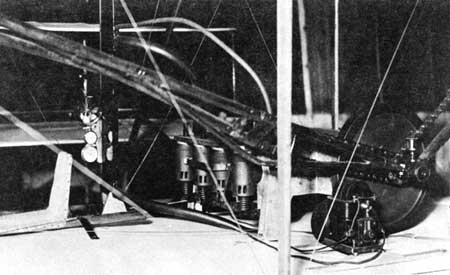

Arrangement of propeller-driving chains and casings on original

Wright 1903 machine displayed in the Smithsonian Institution.

Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution.

The brothers decided to use, two propellers on their powered machine for two reasons. First, by using two propellers they could secure a reaction against a greater quantity of air and use a larger pitch angle than was possible with one propeller; and second, having the two propellers run in opposite directions, the gyroscopic action of one would neutralize that of the other. The two pusher-type propellers on the 1903 powered machine were mounted on tubular shafts about 10 feet apart, both driven by chains running over sprockets. By crossing one of the chains in a figure eight, the propellers were run in opposite directions to counteract torque. The propellers were made of three laminations of spruce, each 1/2 inches thick. The wood was glued together and shaped with a hatchet and drawshave.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |