|

Amache National Historic Site Colorado |

|

NPS photo | |

Amache, Colorado

WWII Granada Relocation Center

Prowers County, Southeastern Colorado

".. .sprang up overnight where a short time ago only sagebrush, cactus, and Russian thistles survived the winter snow and the hot summer sun."

—War Relocation Authority, 1943

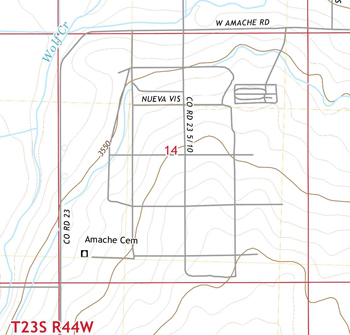

During World War II, the Granada Relocation Center stretched across 16 square miles of Prowers County. Amache was one square mile surrounded by barbed wire fences and armed guards in watchtowers.

Amache was the 10th largest city in the state of Colorado. With 7,500 internees confined to a square mile, the camp was 50% more densely populated than New York City. Amache's residents were men, women, and children of Japanese descent, mostly native-born citizens.

On February 19, 1942, two and a half months after the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese warplanes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the forced removal and internment of all persons of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a civilian agency established by executive order to organize the removal, relocation, and internment of persons of Japanese descent. The WRA was empowered to employ personnel and purchase property, as well as to design and administer all aspects of the internment program including employment of the internees in civilian jobs or for WRA-managed industries.

Many of the internees had a week or less to dispose of any property they could not carry in two suitcases. Cars, stores, houses, pets, toys, and clothing were sold for pennies on the dollar or abandoned. Of the 126,000 Japanese-descended people then living in the US, twothirds were native-born US citizens.

Nevertheless, over 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans were evicted from their homes and imprisoned — under armed guard — in ten WRA detention centers located in isolated rural areas where harsh living conditions prevailed. Over 11,000 people of German ancestry and 250 of Italian ancestry were also interned during World War II, as well as over 2,000 Japanese Latin Americans who were deported to the United States for imprisonment.

"We of America can bring no honor to ourselves nor commend Democracy and the American way of life to others by surrendering to hysteria, or by persecuting the enemy within our gates, little less the loyal, American-born and law-abiding Japanese who consider America their home."

—Rev. Rufus C Baker, Boulder Ministers' Association, Letter to Governor Ralph Carr, April 17, 1942

The WRA operated makeshift camps in various places including horse stalls at the Santa Anita racetrack in southern California. Internees were assembled at these temporary facilities until the permanent camps were hastily constructed in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming.

After assembling in towns and cities near their homes, the internees were transported in trains, trucks, and buses for imprisonment in camps that were strategically placed where labor was required in local agriculture or manufacturing, but far from population centers to reduce the possibility of escape. Population in the camps varied from 7,500 at Amache to 20,000 at Poston in Arizona.

The sprawling Relocation Center was named for the nearby town of Granada, but mail addressed to internees at "Granada, Colorado" overwhelmed the town's post office. A separate postal designation of "Amache, Colorado" was suggested by then Lamar mayor R.L Christy, for the Cheyenne wife of John Prowers after whom Prowers County was named. "Granada" remains the WRA official designation, but former internees and their descendants refer to it as Amache.

Construction

Construction of Amache began on June 12, 1942, with over 1,000 workers including 50 evacuee volunteers. The Center opened in August 1942 and was filled to capacity by October. At its peak, Amache held 7,597 internees from central and southern California, two-thirds of whom were US citizens.

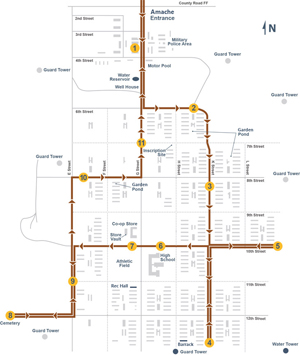

Amache was surrounded by barbed wire fences and eight guard towers that were manned by armed guards. Although the enclosure resembled a prison from the outside, inside was a large city. It included police and fire departments, a 150-bed hospital, stores, and a post office, as well as all the basic community services including a newspaper, schools, churches, and cemetery. Professional inmate workers including doctors and teachers earned from $12 - $19 a month while Caucasian teachers were paid over $100 a month. Amache residents came from varied backgrounds. There were lawyers, dentists, engineers, scientists, businessmen, farmers, fishermen, gardeners, entertainers, as well as artists including a classical opera singer, and two Walt Disney cartoonists.

Education

Pre-school, elementary, and secondary schools opened on October 12, 1942, offering classes for the nearly 2,000 interned school-age children. The school's isolation added to the usual educational challenges: Amache's school administrators described, "unsatisfactory living conditions, unappetizing food, and transportation worries lowered the morale and enthusiasm" of teachers, noting "the rate of turnover was excessive."

"Frequently children showed a need for more sleep. Parents reported the problems confronting them in getting the children to bed early since the family lived in one room."

"All of these rebuffs and disappointments had their effects upon the morale and attitude of student groups. It was extremely difficult to teach the ideas and ideals of democratic society and to urge their relocation when constant reminders confronted boys and girls with evidences of prejudice and undemocratic procedures."

The Land

The Granada Relocation Center included a vast expanse of 16 square miles used to raise livestock and grow a wide variety of produce. It was one of the largest and most diversified agricultural enterprises of the ten major detention camps.

About half of Amache's internees had been gardeners or farmers when they lived in California. During the years they were held at Amache, over 3,000 internees were employed by the WRA in the agricultural and farming programs.

The farm program included raising vegetable crops, feed crops, beef and dairy cattle, poultry, and hogs. Even the high school had a 500 acre farm that was run by vocational agriculture students.

In May 1943, the agricultural projects at Amache encompassed 5,600 acres of vegetables, grain, alfalfa, and pasture lands. The land under cultivation included parts of the XY and Koen Ranches that were purchased by the WRA at the start of World War II. The intensive farming and animal husbandry conducted at the Granada Relocation Center required water rights from the Lamar, Manvel, and XY canals, which the WRA purchased.

Military Service

Amache had the highest rate of volunteerism of all the camps: ten percent of the population volunteered for military service. Amache internees served in many units including the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team, as well as the Women's Army Corps and the Nurses Army Corps. Amache soldiers received 38 combat pins and badges for conduct under fire as well as various other medals and citations. While some internees embraced the opportunity to serve their country, others protested the idea of military service while they and their families were imprisoned and living under armed guard. In July 1944, 11 young men from Amache received 10-18 month sentences for draft evasion. Nearly three dozen Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) soldiers from Amache lost their lives in World War II.

In 1983 the Denver Central Optimist Club placed a monument with the following inscription at the Amache cemetery: "Dedicated to the 31 patriotic Japanese Americans who volunteered from Amache and dutifully gave their lives in World War II, to the approximately 7,000 people who were relocated at Amache, and to the 120 who died here during this period of relocation, August 27, 1942 — October 14, 1945."

Within the Barbed Wire

The one-square-mile camp was surrounded by a four-strand barbed wire fence, with eight guard towers along the perimeter equipped with searchlights and staffed by armed military police. The Amache towers were unique for their octagonal lookouts. The only entry gate was near the center of the north side, about a half mile south of US Highway 50.

The buildings at Amache were laid out on a north-south grid like most of the other internment centers. But its 560 buildings were of superior construction than those in the other nine major camps because Amache was the WRA's showcase for visiting government officials and politicians. Instead of post and pier foundations, which broke and blistered in the desert heat, Amache's barracks generally had concrete perimeter foundations with solid brick or slab floors. These buildings were also finished with fiberboard or asbestos shingles rather than tar paper common at most of the other detention centers.

Amache had 30 residential blocks. Each block included 12 barracks used for living quarters, one for the mess hall, and one for recreation. Many blocks used their recreation barracks as a community hall for civic groups such as the Red Cross, Boy Scouts, YMCA, nursery schools, and churches.

Each block also had one multiple-use building with toilets, showers, and laundry areas. Without toilet facilities in the barracks, internees had to walk through the cold and dark of night and brave blizzards and dust storms to reach the military-style, unpartitioned latrines. The dehumanizing lack of privacy for personal hygiene was one of the fundamental complaints, especially among the elderly.

The slab foundations of most Amache mess halls, communal latrines, and laundry buildings are still in place. Many of the barracks foundations are also intact at Amache because of the concrete perimeter foundations, some of which rise nearly two feet above the ground.

The small building at the cemetery had a concrete foundation, brick walls, and a corrugated metal roof over a wood frame. It was apparently constructed by the internees to store cremated remains and is depicted on the September 1944 WRA map, just west of the grave sites. Shortly before Amache was closed, internees placed a polished granite memorial inside to honor those who died there while imprisoned. The stone has been vandalized and is chipped in several places by rifle slugs.

Following closure of Amache, the agricultural lands reverted to private farming and ranching. The camp buildings were demolished or sold to local towns, school districts, and the University of Denver.

The camp was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 18, 1994, and designated a National Historic Landmark on February 10, 2006. Today, the only surviving signs of the 10th largest city in Colorado — the Amache detention center — is the small brick structure housing the granite slab memorial, the cemetery, building foundations, roads, and a reservoir. In 2013, the original water tank was restored and a replica guard tower was built.

Life in Amache

Life on the block at Amache centered on the mess hall not only for the three daily meals, but for meetings, classes, and entertainment. The hall measured 40 x 100 feet and held up to 250 people.

"The meals are served cafeteria style, each individual lining up at the counter to receive his plate and then sitting down at a long wooden table. The kitchen personnel is comprised entirely of internees." —WRA

Meals combined American and Japanese food, but the assemblyline service and mass seating made the traditional family mealtime impossible. The customarily close-knit Japanese family structure was further undermined by the institutional regulation of daily life.

Amache high school, with its multi-purpose auditorium/gymnasium, was reputedly the most expensive building in Prowers County, which led to outsider complaints of partiality toward the internees at Amache. On November 4, 1942, the Amache newspaper, the Granada Pioneer, reported that the US Congressman from northern Colorado, William S. Hill, wrote to the Greeley Tribune that he had received "many letters protesting the fine treatment received by Japanese in relocation centers," and that he sought to "squelch rumors" about favoritism toward the internees.

The Granada Pioneer noted in its first edition, published October 14, 1942, that the assistant project director, Donald E. Harbison, announced that permits for internees to shop in the nearby town of Lamar had been "curtailed" because the small stores there could not support the needs of the internees as well as their local customers. The internees were apparently "leaving little for farmers who go into town to exchange their eggs and produce for manufactured goods." The Pioneer noted that exceptions would be made for medical and dental emergencies, but only with a doctor's certificate.

Amache was soon served by a 150-bed hospital. Illness was a constant threat because of the dense living conditions in the camp. The Granada Pioneer regularly mentioned outbreaks of illnesses on various blocks and noted in the summer of 1944 that the camp must go "all out" to combat polio.

The residents of Amache soon became virtually self-sufficient. In mid-November 1942, each residential block received five sewing machines and internees established a tofu factory by the fall of 1943. The camp consumer's cooperative — Amache Consumer's Enterprises Inc. — was one of the largest in Colorado. Its 2,387 members owned nearly 5,000 shares and operated a clothing store, variety store, shoe store, shoe repair shop, dry cleaner, barber shop, beauty parlor, canteen, watch repair shop, and an optometry. The coop's gross sales totaled more than $40,000 per month.

The many skilled professionals and crafts people in the camp were a rich source of knowledge for adult night classes. Instruction was offered in a wide variety of areas such as typing, shorthand, English, dressmaking, drafting, woodcarving, painting, embroidery, poetry, Japanese calligraphy, flower arranging, and bonsai. The recreation program included movies, plays, concerts, sports, talent shows, and exhibitions.

"...passage from room to room, to library, office, or lavatory, could be attained only by stepping out in the periodic fury of dust and sand."

—Amache school principal

Internees skilled in farming and gardening established ornamental gardens, often improvising creative methods of specialized irrigation and soil treatment to soften the stark and arid landscape within the residential area. Amache's sandy soil became wind-blown when the native vegetation was removed, so gardening provided a practical ecological function as well as a psychological function of "place-making" — giving one's environment a personal touch.

The ornamental gardens around the Amache school may have been in response to a comment by the Amache school principal who wrote, "passage from room to room, to library, office, or lavatory, could be attained only by stepping out in the periodic fury of dust and sand." Researchers at the on-going archaeological dig at Amache have noted that dozens of schoolchildren submitted landscaping plans for the school.

(click for larger maps) |

Regulation and Administration

The internees, with the exception of the Issei (first-generation Japanese) comprised the camp's governing body. Representatives were elected from each block for the Block Managers Assembly. Five of the block representatives were chosen to serve on an executive council with three WRA administrators. The council passed laws and regulations, in addition to the WRA regulations, and appointed the judicial and arbitration commissions.

The Amache Post Office was managed by five Caucasian civil service personnel who were assisted by an internee postmaster and six internee clerks. Fifteen internee mail carriers delivered mail daily.

The Amache Fire Department was equipped with two up-to-date Ford pump trucks. Three crews of 8-10 firefighters worked rotating shifts under the management of Caucasian supervisors and an internee fire chief. Each block also had volunteer auxiliary firefighters.

The Amache Police Department was headed by a Caucasian security officer and modeled on an urban police force with an internee chief, a dozen captains and sergeants, and 48 patrolmen who worked 8-hour shifts. The Military Police who guarded the camp perimeter were not responsible for internal law enforcement.

" . . . nations that forget or ignore injustices are more likely to repeat them."

—Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

Redress and Reparations

Farmland property losses from the 1942 forced removal are conservatively estimated at $72.6 million in wartime (1941-1945) dollars, the equivalent of more than one billion dollars in today's currency. Former internees filed a class-action lawsuit for redress in 1983, but it was rejected on a technicality. Had the class action prevailed, meaningful reparations based on proven losses might have been paid to survivors and to the surviving heirs of former prisoners who died before receiving compensation. Instead, in 1988 the US Congress limited compensation to $20,000, which was paid only to the living former internees who agreed to forever release the US government from further claims. Surviving Japanese Latin Americans who were shipped to the US for imprisonment during WWII received only $5000. Children of persons who lost everything received nothing unless they too had been imprisoned. Ultimately, about one-half of those imprisoned received the token compensation, but the lingering impact of their selective imprisonment — for no reason other than their race — continues to resonate within the Japanese American community.

Source: Friends of Amache Brochure (March 2014)

|

Establishment Amache National Historic Site — March 18, 2022 (authorized) |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of Transplants: A Study of Entryway Gardens at Amache (©David H. Garrison, Master's Thesis University of Denver, August 2015)

Amache Japanese-American Relocation Center (Amache Preservation Society)

Amache: Special Resource Study (October 2022)

Amache Special Resource Study: Newsletter #1 (February 2020)

Amache Special Resource Study: Newsletter #2 (April 2021)

An Analysis of Modified Material Culture from Amache: Investigating the Landscape of Japanese American Internment (©Paul Swader, Master's Thesis University of Denver, March 2015)

Artifacts, Contested Histories, and Other Archaeological Hotspots (Bonnie J. Clark, extract from Historical Archaeology, Vol. 52, 2018)

Auto Tour Podcasts (Amache Preservation Society)

1. Kiosk and National Historic Landmark Marker

2. 6H Garden and Koi Pond, Barracks, Mess Hall, Latrine

2.1. Barracks

2.2. Mess Hall

5. Internee Inscriptions and 9L Social Gardens

7. Co-op

11. Amache Agriculture: Yesterday and Today

Bibliography: Amache (Date Unknown)

Brewing Behind Barbed Wire: An Archaeology of Saké at Amache (©Christian A. Driver, Master's Thesis University of Denver, August 2015)

Communities Negotiating Preservation: The World War II Japanese Internment Camp of Amache (Jennifer Otto, extract from Southeast Colorado Heritage Tourism Report, 2009, ©Wash Park Media)

Community Identity in "The Granada Pioneer" (©Jessica P.S. Gebhard, Master's Thesis University of Denver, June 2015)

Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (HTML edition, UW Press 2002 rev. ed.) Western Archeological and Conservation Center Publications in Anthropology 74 (Jeffrey F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord and Richard W. Lord, 1999)

Cultivating Community: The Archaeology of Japanese American Confinement at Amache (Bonnie Clark, extract from Legacies of Space and Intangible Heritage: Archaeology, Ethnohistory, and the Politics of Cultural Continuity in the Americas, 2017, ©University Press of Colorado)

Densho Encyclopedia: Amache (Granda)

Enabling Legislation: Amache National Historic Site Act P.L. 117-106 (March 18, 2022)

Feminine Identity Confined: The Archaeology of Japanese Women at Amache, a WWII Internment Camp (©Dana Ogo Shew, Master's Thesis University of Denver, June 2010)

Field School Summaries: Amache Research Project (University of Denver)

Summer 2008 • Summer 2010 • December 2014 • 2016 • 2018

Final Report: Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast 1942 (J.L. DeWitt, 1943)

Foundation Document, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado (January 2024)

Foundation Document Overview, Amache National Historic Site, Colorado (January 2024)

Foundation Document (Draft), Amache National Historic Site, Colorado (March 2023)

Granada Pioneer (Amache, Colo.) (1942-1945)

Japanese Americans in World War II: National Historic Landmarks Theme Study (Barbara Wyatt, ed., August 2012)

Japanese American Confinement Sites Digital Collection (National Japanese American Historical Society)

Japanese-American Internment Sites Preservation (January 2001)

Japanese Imprisonment at Amache (Christian Heimburger, Date Unknown)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Granada Relocation Center (Thoma H. Simmons, R. Laurie Simmons, Diane Bell, Greg Kendrick and Kara M. Miyagishima, August 2004)

Newsletter: Amache Alliance

2022: Winter • Spring • Summer

2023: Winter

2024: Spring

Newsletters: Amache Historical Society II

Newsletter: Amache Preservation Society

2016: Chirstmas

Newsletters: Amache Research Project (University of Denver)

April 2009 • Winter 2011 • Spring 2012 • Spring 2013 • Spring 2014 • Spring 2015 • Spring 2016 • Spring 2017 • Spring 2018 • Spring 2019 • Winter 2020 • Spring 2022 • Spring 2023

Perseverance and Prejudice: Maintaining Community in Amache, Colorado's World War II Japanese Internment Camp (Dana Ogo Shew and April Elizabeth Kamp-Whittaker, extract from Prisoners of War: Archaeology, Memory, and Heritage of 19th- and 20th-Century Mass Internment, 2017, ©Springer Science+Business Media)

Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Part 1 (HTML edition) (December 1982)

Short History of Amache Japanese Internment Camp (Date Unknown)

Snapshots of Confinement: Memory and Materiality of Japanese Americans' World War II Era Photo Albums (©Whitney J. Peterson, Master's Thesis University of Denver, November 2018)

Suggestions for Visitors to Granada Relocation Center (Amache) National Historic Landmark, near Granada, CO (Amache Preservation Society, 2021)

The Archaeology of Entryway Gardens at Amache (Bonnie Clark, extract from The Journal of the North American Japanese Garden Association, Issue No. 4, 2017)

The Archaeology of Interment (Archaeology, Vol. 64 No. 3, May/June 2011, ©Archaeological Institute of America)

The Role of Amache Family Objects in the Japanese American Internment Experience: Examined Through Object Biography and Object Agency (©Rebecca M. Cruz, Master's Thesis University of Denver, August 2016)

The Sounds of Being "Un-American": Embodied Cultural Trauma Within Japanese American Musical Worlds (©Kyle Przybylski, Master's Thesis University of Denver, June 2020)

Through the Eyes of a Child: The Archaeology of WWII Japanese American Internment at Amache (©April Kamp-Whittaker, Master's Thesis University of Denver, June 2010)

When the Foreign is not Exotic: Ceramics at Colorado's WWII Japanese Internment Camp (Stephanie A. Skiles and Bonnie J. Clark, extract from Trade and Exchange: Archaeological Studies from History and Prehistory, 2010, ©Springer Science+Business Media)

Whose Community Museum Is It? Collaboration Strategies and Identity Affirmation in the Amache Museum (©Ting-chun (Regina) Huang, Master's Thesis University of Denver, June 2019)

Words Can Lie or Clarify: Terminology of the World War II Incarceration of Japanese Americans (©Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, 2009)

Words Do Matter: A Note on Inappropriate Terminology and the Incarceration of the Japanese Americans (©Roger Daniels, 2005)

Wrestling with Tradition: Japanese Activities at Amache, a World War II Incarceration Facility (©Zachary A. Starke, Master's Thesis University of Denver, August 2015)

An Archaeology of Gardens and Gardeners at Amache Duration: 36:05 (Bonnie Clark, June 12, 2020)

amch/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025