|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 10:

ARKANSAS POST IN THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

In 1775, the American Revolution began. Spain, recognizing an opportunity to be rid of the troublesome British, offered aid to the Patriots. It was reasoned that with American independence, Spain need not fear British aggressions. Arkansas Post had a role in the conflict. Upstream expeditions stopping at the fort received briefings for evading British patrols, and thus kept Spanish-American supply lines open.

Sometime during the summer of 1776, Commandant Orieta died at the post. As his replacement, Governor Louis de Unzaga appointed Captain Balthazar de Villiers. A seasoned officer, De Villiers was a veteran of three campaigns in Flanders. He came to Louisiana in 1749 and served admirably under both the French and Spanish administrations. Unzaga thought De Villiers ideally suited for the difficult command at Arkansas Post. [1]

The new commandant and his wife, Francoise Voisin Bonaventure, reached Arkansas Post in September, 1776. De Villiers found a pitifully small French and Spanish community. Among their number were 50 whites and 11 slaves all domiciled in 11 rotting dwellings in the vicinity of the fort. Only 16 soldiers formed the garrison. The fort itself was dilapidated by the annual floods that had plagued the settlement since its relocation in 1756. To Captain De Villiers, Arkansas Post was "the most disagreeable hole in the universe." [2]

De Villiers confronted the problem of contraband trade. The small garrison on the Arkansas was ill-equipped to deal with large numbers of interlopers and relied on their Indian allies to pillage hunting camps and drive out the British. In October, 1776, Spanish Indians raided a British camp and captured 300 deerskins and many beaver pelts. In the spring of 1777, the Kaskaskia tribe, recently located in Arkansas to escape Iroquois incursions in the Illinois Country, aided De Villiers by compelling British hunters to abandon the White River region. It was not until Spain entered the American War of Independence as allies of France and the Patriots, however, that the majority of British departed. De Villiers then turned his attention to improving Arkansas Post. [3]

De Villiers had found the location of Arkansas Post unsuitable. In 1777, he wrote: "all the land [around the post] has been covered with water for three weeks and the entire harvest has been lost," indeed for the fourth year in a row. Heavy rains in the spring of 1779 forced the Mississippi to overflow. The muddy water backed-up the Arkansas River inundating the post. By February 17, there were two feet of water inside the fort. Weary of continual flooding, De Villiers advocated moving the post to higher ground.

Two former sites were favored by De Villiers: the location where the Chickasaw attacked the post in 1749 or Ecores Rouges where De La Houssaye moved the post in 1751. De Villiers preferred Ecores Rouges. He believed that this location was more easily defended and being above the cut-off where the White River entered the Arkansas, would be more effective in keeping British hunters out of the district. Furthermore, De Villiers reasoned that river traffic had slowed so much as a result of British patrols that a site near the Mississippi was no longer necessary. As far as the habitants were concerned, De Villiers believed they would welcome the move.

De Villiers' request to move the post cleared official channels, and on March 16, 1779, the commandant reported that the move to Ecores Rouges had been accomplished. The site selected for the new settlement was three hills on the north bank of the Arkansas River. On the first hill ascending the river, some Quapaw had already settled. On the second hill, De Villiers located a number of Anglo-American families, war refugees from east of the Mississippi. On the third hill he placed the Franco-Spanish families and projected a fort. Before it was completed, however, Spain entered the American war for independence against Britain. [4]

By the time news of the war reached Arkansas Post, Spanish Governor Jose Galvez had captured Natchez, Manchak, and Baton Rouge and was preparing to move against Mobile and Pensacola. Upon hearing that Spain had entered the war, Commandant De Villiers crossed the Mississippi with a detachment of soldiers and civilian witnesses. The band landed at the deserted British station of Concordia on November 22, 1780, and formally ". . . took possession of the left bank of the Mississippi River opposite to the Arkansas, White, and St. Francis Rivers, as far as the limits of the Natchez garrison as dependencies and jurisdictions of this post." [5] De Villiers' shrewd action helped reinforce the post-war claim of Spain to the east bank of the Mississippi and the region north of the mouth of the Yazoo River.

|

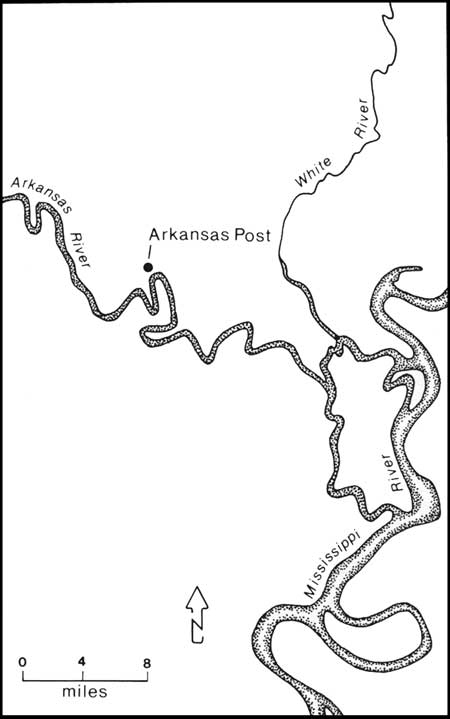

| Figure 19. The location of Arkansas Post from 1779-1812. To escape devastating floods, Arkansas Post was again moved upriver in 1779. |

|

| Figure 20. Arkansas Post and vicinity in 1779. After a sketch drawn by Commandant Balthasar de Villiers. |

During the months following Galvez' action on the Mississippi, the major arena of conflict occurred on the lower Mississippi and in West Florida. In March, 1780, Galvez captured Mobile and soon launched an attack on Pensacola. During the Pensacola seige, insurgents at Natchez under the leadership of John Blommart, rose against the Spaniards. On June 22, 1781, Galvez directed his superior force against the rebels, crushing the rebellion. Blommart and several other leaders were imprisoned in New Orleans. A number of insurgents avoided capture, however, and fled to the Chickasaw, long-time allies of the British. This group united under the leadership of James Colbert. Colbert had been a former British Captain, but retired to the Chickasaw nation following the Spanish capture of Pensacola.

Colbert and the Natchez rebels vowed to disrupt Spanish commerce on the Mississippi and thereby gain the freedom of Blommart and the other insurgents imprisoned in New Orleans. The proximity of this rebel band to Arkansas Post imperiled the Spanish fort.

Commandant De Villiers learned of this newest threat from four Americans who had been imprisoned by the rebels at Natchez. At least one of the rebels, a man named Stilman, formerly resided at Arkansas Post and knew the surroundings particularly well. Thus, De Villiers feared that the rebels posed a threat to the safety of his command. The post inhabitants were fearful for their lives and a day later offered to supply the garrison with pickets for a stockade. De Villiers was overjoyed. [6]

By July 1781, the fort was finally completed. The new stockade, made of red oak pickets, was 13-feet high and about 75-yards to a side. Embrasures in the stockade were covered with bullet-proof sliding panels. A two-foot high banquette surrounded the whole. Inside the fort were a soldiers' barracks, storehouses, and several smaller buildings. De Villiers called his new post "Fort Carlos III" and boasted that the king now has ". . . a solid post capable of resisting anything that may come to attack it without cannon." [7]

Ironically, the first threat De Villiers encountered came from within the garrison. In 1782, two German soldiers—Albert Faust and John Frederick Pendal—and a number of Anglo-American refugees participated in a conspiracy to capture the post for Great Britain. The conspirators planned to open the gates of the fort to British sympathizers who would rush in and butcher the sleeping garrison. Warned by loyal French inhabitants, De Villiers promptly imprisoned the offenders. Both the Germans and two of the Anglo-Americans were tried, found guilty of treason, and executed in New Orleans. [8]

Meanwhile, Colbert and his partisans were attacking Spanish boats on the Mississippi, disrupting the supply line and placing Arkansas Post in a precarious position. Because of successive floods and drought, post residents had to rely almost exclusively on outside sources of food. [9] On May 2, 1782, Colbert's band captured a boat at Chickasaw Bluffs. On board the vessel was Nicanora Ramos, the wife of the Spanish lieutenant governor of St. Louis, and her four sons. Colbert tried unsuccessfully to exchange his hostages for Blommart. After a 20-day captivity, Colbert released his prisoners, vowing next to capture the Spanish post on the Arkansas. The former prisoners reported this information to Governor Esteban Miro, who responded by dispatching Antonio Soler, second lieutenant of artillery, with a supply of ammunition, two swivel guns, and orders to put the fort into a state of readiness. [10]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006