|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 12:

SPAIN ATTEMPTS TO HOLD LOUISIANA

After the American War for Independence, Spain renewed her attempts to develop Louisiana. Official policy favored the colonization and agricultural development of the province. It was reasoned that a substantial population in Louisiana would act as a barrier to the westward movement of Americans, thus preventing their penetration of Spain's southwestern colonies. Simultaneously, Spain confronted problems in controlling contraband trade and the aggressive Osage on her western border. Hearing rumors almost daily of an impending American or French invasion, officials kept the Spanish military presence in Louisiana strong.

Following the war, an alarming number of American emigrants moved into the fertile lands west of the Appalachians. Spain hoped to check this tide of American expansion by cultivating the loyalty of Indian tribes between the Spanish and American frontiers. In 1783, Spain concluded a formal peace with the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians. Raids by American frontiersmen against former British allies, however, displaced many other tribes who abandoned their homelands to seek refuge in Spanish territory. Spanish hospitality attracted the Delaware in 1786 and almost the entire Miami-Piankeshaw band to the Arkansas country in 1789. The presence of additional tribes under Spanish jurisdiction strengthened the barrier against American expansion and increased the volume of trade conducted at Spanish posts. Unfortunately for Spain, commercial opportunities in Arkansas also attracted large numbers of American traders.

Americans conducted illegal contraband trade with Spain's new Indian allies. Early in 1787, 20 Americans from Louisville were reportedly trading with the Delaware on the St. Francis River. To guard against the growing contraband trade, Governor Miro sent a detachment of the 6th Spanish Regiment, commanded by Captain Don Joseph Valliere, to the Arkansas. Valliere reached the post on March 31, 1787, and succeeded Du Breuil as post commandant. [1]

At the time of Valliere's arrival, the village of Arkansas Post contained 119 civilians. Many were hunters who resided in the Arkansas wilds for most of the year. Permanent post residents included: Francois Menard and his father-in-law Anselme Villet; Juan Gonzalez and Ignacio Contrera, Spanish soldiers discharged from service but who remained to hunt and trade; Martin Serrano, another discharged veteran who married a widow from Arkansas Post; Andre Lopez, a trader from Galicia; Joseph Tessie, post interpreter; Thomas Serrano and Mateo Serra, hunting partners; Jean Baptiste Imbaut, Pierre Nittard, Pierre Picard, Jean Baptiste Cucharin, Michael Woolf, Joseph Baugy, Pierre Ragaut, Pierre Lefebre, Henry Randall, Robert Gibson, Bayonne, Duchasin, Michel Bonne, William Nolan, and Baptiste Macon, post residents. [2]

|

| Figure 21. Captain Josef Valliere, commandant at Arkansas Post from 1787-1790. Original painting owned by Mr. and Mrs. Howard Stebbins, Little Rock. |

On March 31, Valliere and the former commandant, Jacobo Du Breuil, made an inspection of the fort. The transfer of soldiers of the 6th Regiment had increased troop strength to 32 men. Among the artillery of the fort were two 4-pound cannon in fair condition and two 1/2-pound and five 4-ounce swivel guns in good condition. The stockade of the fort, however, was sadly in need of repair.

Valliere inherited the problem of improving the dilapidated fort. Although the location at Ecores Rouges placed the post above the level of destructive flood waters, the swift current of the Arkansas now undermined the very bank upon which the fort stood. In 1787, four rises of the river badly eroded the bank below Fort Carlos III. By the end of the year, only 18-inches of overhanging esplanade remained, forcing Commandant Valliere to remove the artillery. For reasons of safety, the captain sent his wife and child to New Orleans to live. In February, 1788, another rise of the river tore away a bastion and a month later, the stockade wall nearest the river tumbled down the bank. Little remained of Fort Carlos III, and the garrison took quarters beyond the ruined enclosure. In 1789, a spring running through the fort undermined what was left of the stockade. In spite of frequent complaints to the governor, a lack of funds delayed construction throughout the commandant's tenure at the post. [3]

Notwithstanding the poor state of Arkansas defenses, Commandant Valliere pursued his duties with conviction. On March 12, 1788, four soldiers deserted the garrison at Arkansas Post to join the Americans trading illegally with the Delaware on the St. Francis River. The great profits that could be reaped in the fur trade enticed many soldiers who earned only $6-$9 per month. Commandant Valliere resolved to capture the deserters and expel the troublesome smugglers. Valliere mounted an expedition. A file of soldiers approached the American camp by land while a naval force of Indians under the leadership of Interpreter Joseph Tessie approached on the river. Perhaps warned of Valliere's plans, the Americans had abandoned their camp. The expedition led to no beneficial conclusions for the Spanish and incurred expenses that the governor considered exorbitant. Citizens in the militia earned soldiers pay for time served. Hereinafter, the overzealous Valliere was cautioned, let the Indians control American trespassers.

The post merchants were angered that the Americans had effectively stolen the Delaware commerce. In retaliation a prominent post trader, Francois Menard, instigated ill-feelings between the Quapaw and Delaware. Menard suggested to the Quapaw that the contraband goods the Delaware received from the Americans were superior to Spanish goods. Before trouble could develop, Valliere had the man put in the public stocks, sending him with the next available convoy to New Orleans for trial. [4]

Even more serious than the troublesome American traders, Spain constantly feared an American military invasion. In February, 1788, Governor Miro suspected an invasion from the Tennessee area. He reinforced the Arkansas garrison with a sergeant and 12 additional soldiers. One half of the detachment established an outpost on an island in the Mississippi to watch for the invading army. The other half quartered at Arkansas Post and relieved the outpost every 15 days. The expected invasion never materialized, however, and the outpost proved to be nothing more than an unnecessary expense.

In 1790, a transfer of command placed Captain Juan Ignace Delino de Chalmette in charge of the Arkansas garrison. At his arrival on July 20, the new commandant must have been dismayed to find no trace of Fort Carlos III. The fort had long since surrendered to the Arkansas River. The 30 man garrison De Chalmette commanded was quartered in temporary barracks without a stockade.

Soon after De Chalmette assumed command, the citizens of the post presented him with a memorial requesting "a little fort" to protect us from "various Indian tribes who incessantly molest us." [5] The inhabitants generously offered to supply stakes for the new stockade. De Chalmette purveyed this most recent request to the Governor and on January 20, 1791, permission to construct a new fort was granted, provided the cost of the new work did not exceed $1,500.

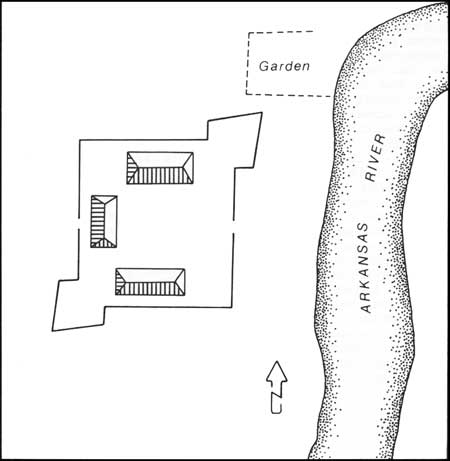

Commandant De Chalmette selected a location for the new fort next to the habitant's fields and within a "cannon shot" of the village. By March 1, 1792, the captain took possession of the fort, naming it San Esteban after the governor's given name. The new works included a house, barracks for 50 men, and a warehouse. For protection against the Indians, a stockade was constructed of white oak stakes arranged in a square with two opposing bastions at opposite corners. Four 6-pound cannon and 2 swivel guns were mounted in the bastions. The nearby habitant village contained about 30 houses of the French style with full galleries and shingle-covered exteriors. The houses were set along two streets. Below the fort were the habitant's fields, 44x44 feet in size, where "beautiful fields of wheat" were maintained. [6]

The civilians of Arkansas Post were relieved that a fort protected their community once again. A year after the treaty of 1777, the Osage resumed aggressions against the Spanish. In 1787, hunters found two men and a woman murdered by Osage on the Arkansas River. Several hunters' camps along the river were burned. One demoralized post habitant commented that "we are robbed by the Osages not only of the products of the hunt but even of our shirts." Angered by continued Osage harassment, Governor Baron de Carondelet declared war on that tribe in May, 1793. Following official orders, De Chalmette mounted a force of 50 to 60 white hunters and 150 Quapaw to march against the Osage. The inhabitants were determined "to punish the Osages for their cruelty towards [them]." Before the expedition could be launched, however, another threat of an American invasion compelled the governor to abandon the punitive expedition and seek more peaceful means of reaching a truce. The Osage continued to be troublesome to the Spanish throughout the remainder of their Louisiana occupation. [7]

In 1793, war between Spain and the new French republic began. Officials feared that the revolution would spread to Louisiana or that a French invasion would occur. Later in the year, Spanish officials learned that Edmond Genet, citizen of the French republic, and American General George Rogers Clark planned to invade Louisiana. In response to this threat, De Chalmette called out the Arkansas militia. Governor Carondelet believed that the Arkansas fort was little more than "a circle of stakes" and hardly worth defending. He denounced De Chalmette's action as wasteful and informed the commandant that in the face of a superior invasion force he should abandon the post and retire to Los Nogales, present-day Vicksburg. Perhaps because of his excessive response to the invasion rumor, De Chalmette was relieved of command. [8]

On July 11, 1794, Captain Carlos de Villemont replaced De Chalmette as commandant of Arkansas Post. De Villemont was 27 when he assumed command. The young officer impressed Spanish officials and soon earned the respect and admiration of the post residents. It has been said of De Villemont that "he united an almost princely sauvity [sic] of manners with a character that was without blemish." De Villemont served as commandant of Arkansas Post for eight years, longer than any other officer. In 1800, he married a local woman and raised six children at Arkansas Post. Following his retirement in 1802, the former commandant spent the remainder of his years on the Arkansas. [9]

The threat of an American invasion continued to alarm Louisiana officials. On July 22, 1795, Spain responded by ceding its claims to the east bank of the Mississippi between the mouth of the Yazoo and the 31st parallel to the United States. The loss of several strongholds east of the Mississippi compromised Spanish defenses and did nothing to appease American desire for land. Forced to reassess their Louisiana policy, Spanish officials decided that the best way to diffuse an American invasion was to populate the province with settlers. Ironically, because Spanish subjects preferred to settle elsewhere, Louisiana officials had to rely on Americans—the very people she sought to exclude—to settle in Louisiana. The governor instructed Commandant De Villemont to invite Americans from Vincennes and Detroit to settle in Arkansas. [10]

The Spanish government was careful to select industrious pioneers to settle in Louisiana. Two such men were the brothers Elisha and Gabriel Winter. Sometime between 1790 and 1798, the Winters traveled to New Orleans and established a business making cotton rope. As recompence for introducing a manufacture into the province, the men received a tract of one million arpents (1 arpent=11 square feet) on the Arkansas River. The Winters invited Joseph Stillwell, a revolutionary war veteran homesteading in Kentucky, to emigrate to Arkansas with them. In 1798, Elisha and Gabriel Winters, a third brother named William, and Joseph Stillwell settled on their grant in Arkansas. Other American settlers homesteading in the same year included William Hubble, William Russell, Walter Carr and three brothers named Samuel, Richard and John Price.

Pierre Massieres, whose contraband goods Jacobo Du Breuil once confiscated, settled at the post and became a respectable merchant. [11]

The success of Spanish policy in Louisiana was never tested. Ultimately, the province proved to be too great an economic burden for Spain. In 1800, the treaty of San Ildefonso was concluded by which Spain retroceded Louisiana to France in exchange for the Duchy of Parma in Italy. France, however, never took formal possession of the province. In 1803, the United States purchased Louisiana from Napolean Bonaparte, emperor of France, for the sum of fifteen-million dollars. On December 20, Louisiana was formally transferred to the United States. One month later, the Spanish commandant transferred the fort on the Arkansas to United States representative, Lieutenant James B. Many.

|

| Figure 22. Fort San Esteban. Constructed by the Spanish in 1792, Fort San Esteban was regarrisoned by American troops in 1804 and thereafter called Fort Madison. After an 1806 sketch by John B. Treat. |

As with any change of command, both men prepared an inventory of the fort that listed a barracks, kitchen store house, earthen oven, three sentry boxes, and one flag-staff. The fort was regarrisoned with 16 American troops and thereafter called Fort Madison. [12]

Under Spanish jurisdiction, Arkansas Post served as one link in the Spanish frontier barrier designed to prevent Anglo-American penetration into rich Mexico. Her isolationist policy enticed Spain to enter the American War for Independence on behalf of the Patriots. Spanish officials reasoned that, with American autonomy, British pressure on the eastern border of New Spain would end. The Patriots won their freedom but, unfortunately for Spain, the new United States proved to be more aggressive than Great Britain. The tiny garrison on the Arkansas, like other isolated Spanish posts, was ill-equipped and understaffed. Arkansas Post could not keep Americans from trespassing on Spanish lands. To rectify this problem and strengthen the frontier barrier, Spanish officials proposed to settle Louisiana with agricultural families. If Louisiana were already settled, thought the Spaniards, there would be little reason for Americans to move west. Because Spanish subjects preferred to settle elsewhere, however, Spain eventually invited Americans—the very people she sought to exclude—to populate the province. This same policy, some thirty years later, would lose Texas for Mexico. In reality, Spanish policy in Louisiana was never tested. For reasons of economy, Spain entered a transaction with France that eventually placed Louisiana in the hands of the United States. With the extension of American control over the interior of the continent, peace came to the new frontier and westward immigration continued.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap12.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006