|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 14:

ARKANSAS POST, TERRITORIAL CAPITAL

Demise of the government factory heralded a new economic era at Arkansas Post. An agricultural economy slowly supplanted the waning fur trade. Since 1804, American farmers had been trickling into the region. In 1812, war with Britain sent many displaced Americans west of the Mississippi. To administer the increased population, Arkansas County was created on December 31, 1813, encompassing much of the present state of Arkansas with the county seat at Arkansas Post. The county was administered by the Territory of Missouri. In January, 1815, the battle of New Orleans ended the war with Britain giving yet additional impulse to westward emigration. [1]

Because of the influx of farming families, life at Arkansas Post changed considerably. In 1817, an emigrant stated that most inhabitants had "given up this mode of life [hunting] for the cultivation of land." [2] Instead of dealing in pelts, post merchants now catered to farmers. Eli J. Lewis, William Drope, and Frederic Notrebe transacted nearly all the post business. [3] The village of Arkansas Post now boasted a mill and one hotel. Several Americans joined the French and Spanish to live in the village. The number of civilian residents now totaled nearly two-hundred, larger than any other time during the existance of Arkansas Post.

|

| Figure 24. A typical American farmer. American farmers gradually replaced French trappers. From The Great South by Edward King. |

The residents of Arkansas County grew increasingly dissatisfied with their citizenship in the Missouri Territory. Public improvements and other benefits resulting from territorial organization eluded Arkansas County. In a number of public meetings held at Arkansas Post, the residents of Arkansas County drafted petitions to Congress, urging that their county be separated from Missouri and made a self-governing body. By an act of Congress on March 2, 1819, Arkansas became a territory with the capital at Arkansas Post. The territorial government included a governor, secretary, a general assembly composed of a house of representatives, and an upper house called a council. The highest court included a superior court of three appointed judges. President James Monroe filled the most important offices. He appointed Brigadier General James Miller as governor; Robert Crittenden as secretary; and Andrew Scott, Charles Jouett, and Robert Fetcher as judges for the superior court. [4]

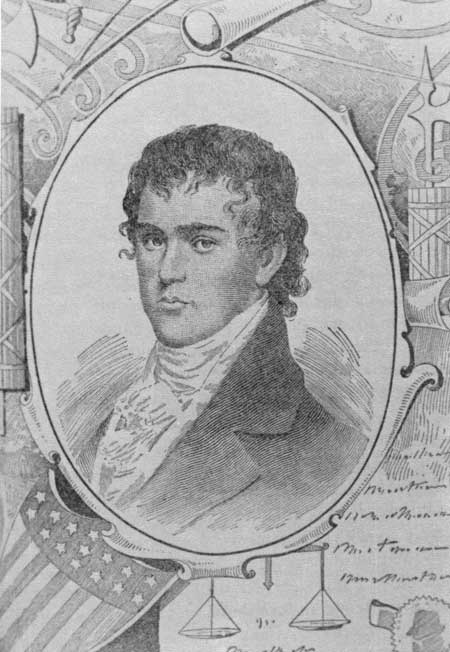

James Miller was born April 25, 1776, at Petersborough, New Hampshire. The young Miller was educated for the bar, but in 1808, entered the army as a major. During the War of 1812, Miller distinguished himself as a leader and rose quickly through the ranks. In August, 1812, he was breveted colonel for meritorious service at Brownstown. Two years later, Miller was promoted to brigadier general for his heroic action at Lundy's Lane. In this encounter, Miller was asked to lead a company of soldiers in an assault on a battery of British guns that had been dealing destruction to American lines. Colonel Miller replied "I'll try, sir." Miller's company advanced and after a short, desperate contest, captured the battery. Miller became an instant hero, and the modest phrase he coined was on the lips of every American. Further feats of daring at Chippewa, Niagara, and Fort Erie won the general a medal from Congress. Miller resigned from the Service on June 1, 1819, when he was offered the governorship of Arkansas Territory. [5]

|

| Figure 25. James Miller, Arkansas' first territorial governor. From Pictorial History of Arkansas by Faye Hempstead. |

On October 17, 1819, the war hero began his journey to Arkansas Territory. The trip was agonizingly slow, taking a total of 75 days after departing Pittsburgh. Miller stopped at nearly every river town to be cheered by admiring crowds eager to see the hero who coined the memorable words "I'll try, sir." Miller's grand arrival at Arkansas Post was described by a citizen:

He came up the river in a splendidly fitted-up barge with a large and well finished cabin, having most of the conveniences of modern steamboats. On the after part of the cabin, on both sides, her name, "Arkansaw," [sic] was inscribed in large gilt letters. She had a tall mast, from which floated a national banner with the word "Arkansaw" [sic] in large letters in the center, and the words "I'll try sir!" . . . interspersed in several places. [6]

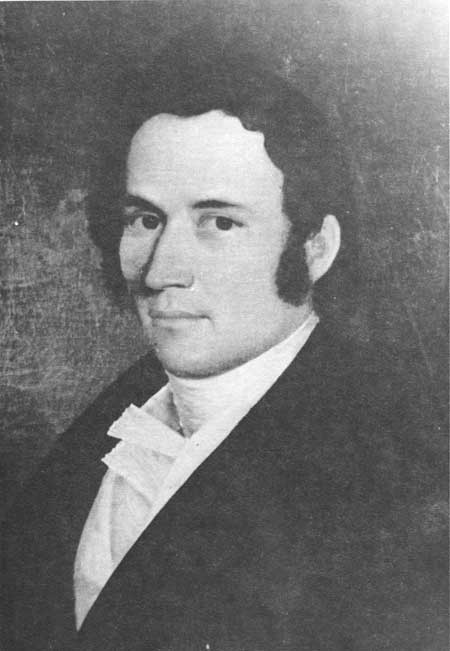

In the absence of the tardy governor, Secretary Robert Crittenden set the wheels of government in motion. At the first session of the territorial legislature, July 28-August 3, Acting Governor Crittenden held elections for the general assembly and filled the most important appointive offices. Governor Miller, upon his arrival, questioned the legality of these elections and called for a special session of the legislature. The legislature reconvened from February 7-10, 1820. Predictably the members unanimously supported their election to office. Other issues discussed during the second session included adoption of a code of laws for the territory, selling public land, road building, making treaties with Indians residing in the territory, and passing a pre-emption law. [7]

|

| Figure 26. Secretary of the territory, Robert Crittenden. Crittenden set the wheels of government in motion during Governor Miller's absence. From Pictorial History of Arkansas by Faye Hempstead. |

The village on the Arkansas prospered as the territorial capital. Just prior to territorial organization, British naturalist Thomas Nuttal visited Arkansas Post and described it as "an insignificant village [that] scarcely deserved geographic notice." On January 15, 1820, Nuttal stopped at Arkansas Post for a second time and found an entirely different community:

Interest, curiosity, and speculation, had drawn the attention of men of education and wealth toward this country. Since its separation into a territory; we now see an additional number of lawyers, doctors, and mechanics. The retinue and friends of the Governor together with the officers of justice, added also essential importance to the territory, as well as the growing town. [8]

Following creation of the territory, Arkansas Post assumed the appearance of an established community. Early businesses included three general stores, William Montgomery's tavern, two tailor shops, a post office, Samuel Wilson's blacksmith shop, Francis Vaugine's billiard parlor, a mill, and two cotton factors. [9] A hoard of lawyers descended on the fledgling capital and opened offices. On October 30, 1819, pioneer journalist William Woodruff set-up a printing press at Arkansas Post.

Woodruff was 23 years old when he came to Arkansas. In appearance, he was a "short man, clean-shaven, with a fine forehead, thin, dark-auburn hair, piercing dark eyes and a reserved manner." To all who knew him, Woodruff was an educated man "of the highest kind of honesty an downright and thorough sincerity." [10] The young publisher learned the printing trade in Brooklyn, New York, and moved around for several years looking for a suitable place to practice his profession. When he heard that Arkansas Territory had been established, the enterprising Woodruff purchased a Ramage printing press, some type, and other supplies and headed for Arkansas Post. The printing press was transported upriver in a bateaux a small raft made by lashing two pirogues or wooden dugout canoes together. Woodruff built a two-room log cabin at Arkansas Post, and on November 20, 1819, published the first issue of the Arkansas Gazette. In his first editorial, Woodruff wrote:

It has long been the wish of many citizens of this territory that a press should be established here; their wish is now accomplished; we have established one—which we intend shall be permanent and increase with the growth of the territory. [11]

Civilization had at last come to Arkansas. So overjoyed were the inhabitants that the community celebrated the first publication of the Arkansas Gazette with a barrel of whiskey donated by a merchant.

|

| Figure 27. Pioneer journalist William Woodruff. Woodruff published the first issue of the Arkansas Gazette at Arkansas Post on Nov. 20, 1819. Arkansas History Commission. |

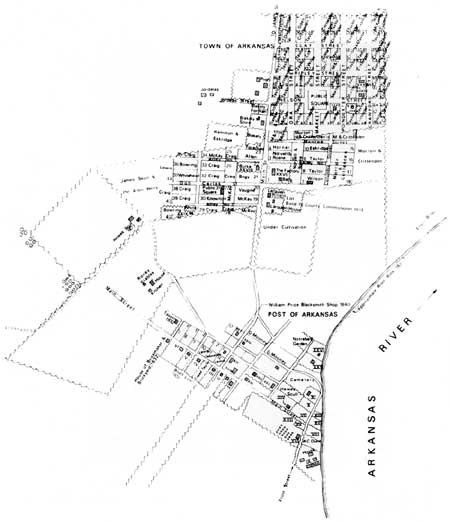

With the presence of public officials and lawyers in the community, all of whom rented space for living quarters and offices, land values soared. Many part-time lawyers engaged in land speculation. In 1818, the Town of Rome, adjoining Arkansas Post, was platted by William Russell, a lawyer. Russell divided the town into 44-consecutively numbered lots, 2 of which were set aside as sites for public buildings. He hoped Rome would become the new county seat. In anticipation, many residents bought lots as an investment. In 1819, William O. Allen, also a lawyer, platted the Town of Arkansas adjoining Rome. Post residents were so certain of the future of Arkansas, that a board of trustees was elected for the newly platted town. [12]

Arkansas Post had become an American community. Yet among most of the original French inhabitants ran a strong current of resentment. Few liked Americans and still fewer liked the American form of government. Washington Irving visited Arkansas Post and observed that the French detest Americans because they "trouble themselves with cares beyond their horizon and impart sorrow thro the newspapers from every point of the compass." Around 1820, many of the French departed Arkansas Post, moving upriver to Jefferson County. Some created the town of New Gascony. A few French habitants were assimilated into American society, however, as evidenced by a sprinkling of French surnames among the village tax rolls. In 1832, Father Saulnier visited Arkansas Post to conduct a Christmas Eve mass. He could muster only 50 people to attend the services. These, he described as "very indifferent and ignorant; they had forgotten nearly everything." [13]

|

| Figure 28. Arkansas Post as the territorial capital. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

With the establishment of the territorial capital at Arkansas Post, the tiny community turned into a bustling American frontier town almost overnight. An influx of lawyers, merchants, and mechanics all but swamped existing facilities. To the conservative French, these newcomers seemed brash and fiercly independent. Such qualities, imparted to American politics, created an atmosphere that could only be described as tempestuous. In early territorial politics, factionalism and prejudice ruled the day. Sometimes, disputes were settled on the field of honor. In 1820, a duel between William O. Allen and Robert C. Oden—the first of its kind in Arkansas—was fought at Arkansas Post.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap14.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006