|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 17:

ARKANSAS POST, COTTON CENTER

Following relocation of the territorial capital, Arkansas Post emerged as a center of the Arkansas cotton trade. Several important events contributed to this economic resurgence including the advent of steamboat transportation, the ready availability of prime agricultural land, and slave labor.

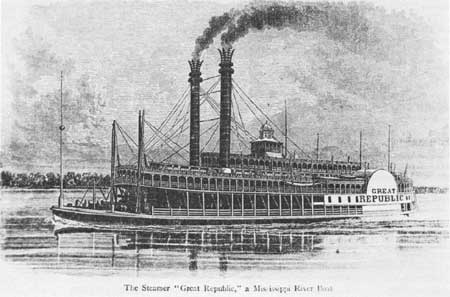

Commanding superior speed and capable of transporting a greater pay-load, the steamboat soon replaced the flatboat and keelboat. On March 31, 1820, Comet became the first steamboat to reach Arkansas Post, and opened the Arkansas River for steam navigation. Upriver establishments like Dwight Mission and the army garrisons at Fort Smith and Fort Gibson created a ready market for supplies, and ensured the continued presence of steamboats on the river. In January, 1821, Comet made a second trip to Arkansas Post followed by Eagle, another steamboat, three months later. A new era of transportation emerged for Arkansas. [1]

With enhanced access to New Orleans markets, prices of merchandise at Arkansas Post dropped overnight. The demand for farm produce shipped to New Orleans increased markedly, and commercial agriculture soon replaced subsistence farming. On November 15, 1824, the Quapaw ceded their remaining tribal lands, some of the richest agricultural land in the territory. The Quapaw had ceded the majority of their tribal holdings in 1818. [2]

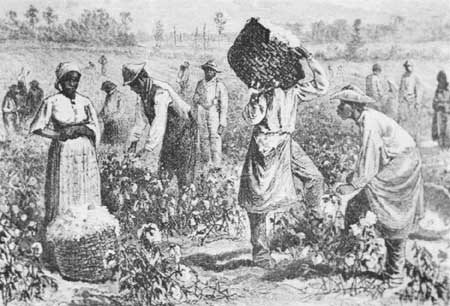

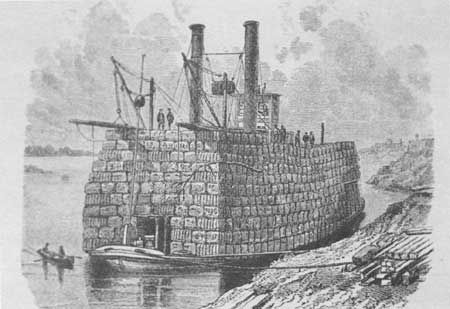

Cotton, the staple crop of the south, gained prominence in Arkansas as did slave labor. The term, "planter," emerged in the local vocabulary. By 1830, cotton dominated the agricultural news of the territory to the near exclusion of other crops. Arkansas Post, abandoned as the territorial capital, emerged as a center of the cotton trade. One resident commented that: "Our little town is all in a bustle. Cotton, the great staple of our country, is crowding in from every quarter. Boats arrive every day at our landing, with the rich production of the climate." At least some indication of this increased prosperity was evident in 1832 when a traveler commented that in addition to the older French houses, a few modern buildings adorned the bank of the river, "among them two brickhouses, one of which was the store and warehouse of the opulent Frederic Notrebe." [3]

|

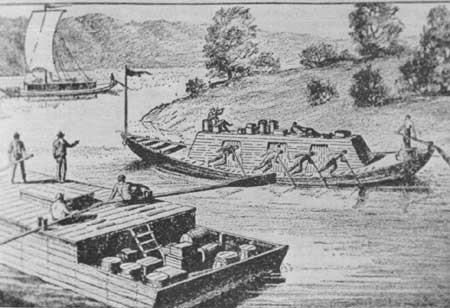

| Figure 29. Transportation on the Arkansas River. Supplies were shipped to Arkansas Post by the flatboat and keelboat. |

|

| Figure 30. A typical Mississippi River boat. These steam powered ships soon replaced the slower flatboats and keelboats. The first steamboat to land at Arkansas Post arrived on March 31, 1820. From The Great South by Edward King. |

Frederic Notrebe was a wealthy planter and the most prominent resident of Arkansas Post. G.W. Featherstonhaugh described him as "the great man of the place [Arkansas Post]." Notrebe was born in France in 1780. After serving in Napolean's army he emigrated to the United States in 1809. He was 29 years old at the time. Notrebe traveled to Arkansas Post and opened a trading house. The enterprise was successful for in 1811, he purchased a lot in town and married Mary Felicite Bellette. Notrebe soon opened a dry-goods store adjacent to his house and catered to the agricultural community. In 1819, he expanded his business to include marketing cotton. When others joined the rush to Little Rock, Notrebe remained, reinvested his profits in land and became a planter. In 1827, Notrebe built a cotton gin. By 1836, the industrious planter owned 14 parcels of land totaling 3,496 acres. In partnership with his son-in-law, William Cummins, Notrebe owned another 4,633 acres. A total of 71 slaves worked his plantations. [4]

"Colonel Notrebe" as he was respectfully called, conducted a large volume of business through his store and cotton gin. He was keenly aware of the shortage of currency in the territory and often conducted business by barter. When Arkansas acquired statehood in 1836, Notrebe labored to establish a branch of the new state bank at Arkansas Post. His efforts were successful. In 1839, a branch of the state bank was established at Arkansas Post on a lot that Notrebe donated. In 1840-1841, a permanent brick building was erected to house the bank at a cost of $15,761.29. [5]

The economic prosperity that Arkansas Post enjoyed during the 1830s soon came to an end. The Arkansas Post branch of the state bank, with outstanding loans worth $91,900, suspended specie payment. An inability to sell state bonds for required capital caused the financial difficulties. In 1843, the Arkansas state legislature passed an act liquidating the entire state bank system. In later years, the costly bank building at Arkansas Post was used to stable horses. [6]

In 1855, a new site at DeWitt, 20 miles north of Arkansas Post, was chosen for the seat of Arkansas County. Arkansas Post languished. In 1856, one traveler commented that "The town at the Post of Arkansas has gone to decay but a few remaining, the County Seat having been removed." [7]

The first half of the nineteenth century brought many changes to Arkansas Post. The sleepy French village awakened as a lively frontier town. Within a few years, economic emphasis shifted from the Indian trade to agriculture. With the availability of large tracts of prime agricultural land, steamboat transportation, and cheap slave labor, cotton gained a foothold in Arkansas. By 1830, cotton was king and Arkansas was a thoroughly southern state. Nowhere was the impact of cotton production felt more than at Arkansas Post. The town became a major river port and center of cotton production. The decade of the 1860s, however, wrought drastic changes in Arkansas and at Arkansas Post.

|

| Figure 31. Working on the plantation. With the support of slave labor, Arkansas Post became a center of cotton production. From The Great South by Edward King. |

|

| Figure 32. A steamboat transporting cotton. Steam-boats laden with cotton bales were a typical sight at Arkansas Post. From The Great South by Edward King. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap17.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006