|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 5:

A PERMANENT GARRISON ON THE ARKANSAS

The French government, eager to protect the growing river commerce and trade with the Indians, established a permanent military garrison on the Arkansas. Late in 1731, First Ensign De Coulange and a 12-man detachment arrived on the Arkansas River. De Coulange located the fort in the vicinity of the tiny habitant village that had emerged from the ruin of Law's colony, on the same site formerly occupied by La Boulaye and De Tonti. Construction of fortifications began immediately. By 1734, two substantial barracks, a powder magazine, and a prison were completed. Since the fort had no storehouse, trade goods were packed in the spaces between gables in the barracks. Presumably, the buildings were enclosed by a log stockade. This establishment and the nearby civilian community were known collectively by the French as Poste de Arkansea or Arkansas Post.

Shortly after De Coulange came to the Arkansas, he was joined by Father Avond, a missionary sent to minister the French and Quapaw. The 600 livres Avond received for his service was barely adequate for survival. The priest domiciled in a "makeshift hut" of mud and logs. "I have lived elsewhere in such dwellings," commented a visiting missionary, "but nowhere did I have so much fresh air. The house is full of cracks from top to bottom." [1]

The few soldiers stationed at Arkansas Post could not possibly police the surrounding country with any degree of effectiveness. To dissuade the British from encroaching on Arkansas soil, the French cultivated the goodwill of the neighboring Quapaw. Medals of friendship were awarded to key tribal members, and presents were distributed to the tribe on an annual basis. In return for this declaration of friendship, the Quapaw provided a police force for the post environs, expelled British hunters operating in the area, and tracked down deserters and runaway slaves. [2]

In most cases, the duty of the soldier was local. Time was relegated between drill, guard duty, and work in the post garden. For this the soldier received a trifling $9 per month. For occasional duty on stockade repair, he received an additional stipend. The daily ration consisted of bread, beans, rice, and salt pork. Occasionally, a liberal allowance of eau de vie or liquor was dispensed to "revive" the troops. Low wages and monotony resulted in a high rate of desertion. Sometimes, however, a threat of Indian attack shattered the boredom of garrison life. [3]

|

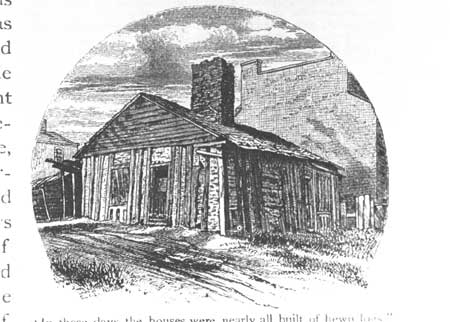

| Figure 12. A typical French house. From The Old South by Edward King. |

In 1733, De Coulange reported that his tiny garrison was "menaced from all sides." Following their defeat at the hands of the French, the remaining Natchez Indians had joined the Chickasaw, staunch allies of the British, and began harassing the French from their lands east of the Mississippi. [4] To the west, the populous Osage nation endangered the post. Days before, these Indians killed 11 French hunters on the Arkansas.

Hostilities on the Arkansas River were only part of a general unrest in Louisiana. Eager to compete with France for the Louisiana trade in peltries, the British agitated the Chickasaw and other eastern tribes against France and her allies. To the alarm of the French, the Osage were also responsive to British overtures. In an effort to halt the erosion of French influence among the Louisiana tribes and stop Chickasaw aggression, French officials organized a campaign against these Indians.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006