|

ARKANSAS POST

The Arkansas Post Story |

|

Chapter 8:

ARKANSAS POST IN THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

Relations with the British had steadily eroded, and in anticipation of a major conflict, the French began to strengthen their military posts. The visit of 1751 to Arkansas Post by Jean Bernard Bossu, a captain of the French marines, confirmed that the fort was not in a defensible condition. Later in the year, Lieutenant Paul Augustin le Pelletier de la Houssaye arrived on the Arkansas with a 50-man detachment and orders to put the post in a state of readiness. [1] De la Houssaye was an accomplished officer whom Governor Vaudreuil described as "exact in his duty." Vaudreuil granted the new commandant a monopoly on the Indian trade. In return, De la Houssaye would pay for the cost of a new post from the proceeds. [2]

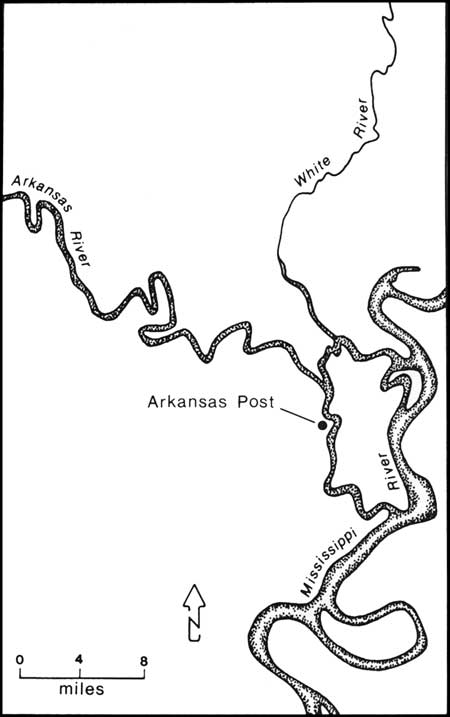

The vulnerability of Arkansas Post, painfully evident after the Chickasaw raid of 1749, prompted the French to relocate in the vicinity of their Quapaw allies. The Quapaw Indians had moved upriver in 1748 because of flooding on the lower Arkansas. The new site, called Ecores Rouges or Red Bluffs by the French, was the first high ground encountered within 40-river miles of the mouth of the Arkansas. [3]

Construction of the new post began in October, and it may not have been entirely finished until 1755. On completion, the fort was enclosed by an 11-foot-high wall of double pickets, 720 feet in length. Platforms for cannon batteries were set in the angles formed by three bastions. Inside the fort, a number of buildings were constructed including officers' quarters, barracks, a chapel, oven, magazine, and latrines. An additional building contained the hospital and storeroom, and also housed the storekeeper and interpreter. A prison occupied the space beneath a cannon platform in one of the bastions. The civilian community, now containing 31 Frenchmen and 14 slaves, relocated near the fort. [4]

War soon erupted between the French and British. Although a pitched struggle over control of the Mississippi River and Louisiana ensued, Arkansas Post was not directly involved in the conflict. Other problems consumed the energy of the tiny garrison.

Safeguarding the commerce of the Mississippi River became a primary concern to the French. Captain de Reggio succeeded De la Houssaye as post commandant in 1753 and three years later, relocated the post near the mouth of the Arkansas. Scarcely nine miles from the Mississippi, soldiers could more easily protect French supply lines. Unfortunately for Arkansas Post, this convenience was not without a price. During the years that the post remained in this location the French fought their own war, a losing struggle against the destructive Arkansas. [5]

|

| Figure 14. The location of Arkansas Post from 175-1756. As a result of the 1749 Chickasaw raid, Arkansas Post was moved further upriver. |

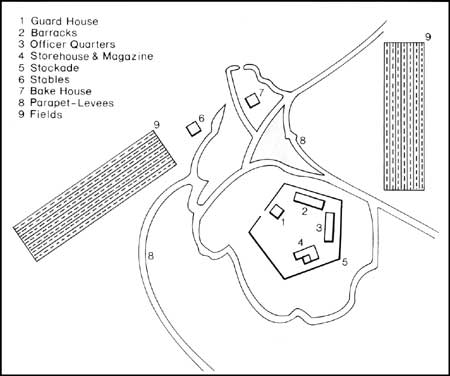

Scarcely one year following the relocation of the post, Captain De Gamon de la Rochette replaced De Reggio. La Rochette possessed a good military record but was "greedy of money, rude and forceful of manner." He soon earned the contempt of his command and Father Carette, the resident missionary. [6] On his arrival, La Rochette found a polygonal stockade surrounded by parapets, as much a measure of flood control as defense. Inside the fort were a barracks, officers' quarters, powder magazine, and commissary. [7] At his disposal, La Rochette had about forty soldiers, including a Polish drummer and two officers—First Ensign Dussau, and Second Ensign Bachemin.

The civilians had located their houses, eight in number, in a line on the river bank. The fort separated them into two groups. At one end lived Etienne Maraffret Layssard, the garde magasin or storehouse keeper. Below Layssard lived Hollindre, a habitant. On the other side of the fort lived Father Carrette, Joseph Laundrouy (post courier), Francois Sarrazin (interpreter), and a habitant named La Fleur.

Layssard was perhaps the most affluent post resident of the day. In addition to his appointment as garde magasin or storehouse keeper, Layssard kept a village wine shop in his home and farmed several fields that he protected from floods with 12-18-inch-high levees. Among Layssard's possessions were 5 slaves, 20 pigs, a milk cow, a flock of chickens, a dog, and a cat.

A particularly wet January in 1758 turned the Mississippi into a raging torrent. The murky brown waters backed-up the Arkansas for many miles, imperiling Arkansas Post. High water topped most of the levees, flooding the lowlands. Only Layssard's garden levee and the parapet of the fort held fast, both scarcely four inches above water. Layssard's house stood on posts above the rising water. Into one room of the tiny dwelling, Layssard crowded his twenty pigs. The second room sheltered Layssard, his wife and four children, five slaves, a dog and cat, and all the squawking chickens he could gather. The cow, for want of space, remained outside knee-deep in water. Other inhabitants, however, were less fortunate.

The flood destroyed Father Carrette's rectory, forcing the priest to say mass in the post dining hall and canteen. Carrette reaped little satisfaction for his efforts among the "snake worshiping" Quapaw and the "immoral" French. The added insult of conducting mass in a canteen was too much to bear. The room, complained Father Carrette, is totally unsuitable as "everything . . . entered there even the fowls." During Father Carrette's final mass, "a chicken flying over the altar overturned the chalice . . . One of those who ought to have been most concerned . . . exclaimed, 'Oh! behold the shop of the good God thrown down!'" So discouraged was Father Carette that he auctioned off his household items and left the Arkansas for good. [8]

Arkansas Post slowly recovered from the devastation wrought by the Arkansas. Improvements at the new fort continued. The bakehouse was enlarged and fortified, and the powder magazine rebuilt. To house Indian allies of France, a lodge built of poles and covered with planks was constructed beyond the fort walls. By the end of the year, the cost of constructing the post escalated to $18,237. Floods continued to be an annual problem. Scarcely five years later, a new commandant would report the fort in ruin. [9]

Meanwhile, the war with Britain was going badly for France. By 1760, the British had won several decisive victories. Anticipating defeat of France in the new world struggle, Louis XV offered western Louisiana to Carlos III, ruler of Spain. Carlos III viewed the province as an economic burden, but because of its proximity to the Spanish southwest, begrudgingly accepted the offer. On November 3, 1762, France ceded Louisiana to Spain by the treaty of Fontainbleau. On February 10, 1763, a treaty was signed ending the war. Great Britain emerged victorious, possessing all of Louisiana east of the Mississippi while Spain now controlled the former French province west of the Mississippi including New Orleans, the provincial capital. France was eliminated as a colonial power on the North American continent. [10]

From its establishment to the Seven-Years War, Arkansas Post played an important role in the development of Louisiana. As the first European settlement in the lower Mississippi valley, Arkansas Post helped establish the claim of France to the Mississippi River. As a river port, Arkansas Post provided a midway stopping point for convoys traveling between St. Louis and New Orleans and, in this capacity, assisted in the development of both cities. The tiny community on the Arkansas River acted as a local center of Indian policy. French traders operating from Arkansas Post established loyalties with upriver tribes. Quantities of pelts, a product of these loyalties, passed annually through Arkansas Post to New Orleans and eventually European markets.

|

| Figure 15. The location of Arkansas Post from 1756-1779. Arkansas Post was moved downriver in 1756 to safeguard Mississippi River convoys. |

|

| Figure 16. Arkansas Post around 1767-1768. After a sketch made by British captain Philip Pittman. |

When Spain assumed control of Louisiana, Spanish officials adopted the French system of administration in favor of their traditional mission system. This turn of events reflected highly on the success of French policy. Yet, the Spanish takeover was not free of problems. French and Indians, distrustful of Spaniards, were wary of the new government. If Spain succeeded in winning the confidence of her new subjects, she would not so easily subdue the British on her eastern border. With France removed from the Mississippi valley, Spain faced a new and more aggressive neighbor.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

arpo/history/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 13-Feb-2006