|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 1: AN ANASAZI VILLAGE MISNAMED AZTEC

THE SETTING

The Animas River heads in the snow melt of the lofty La Plata Mountains of southwestern Colorado and then tumbles southward some 45 miles through successive alpine breaks as it rapidly loses elevation. Near the New Mexico state line it enters the northern bulwarks of the San Juan Basin, where it begins to flatten out in meanders through worn-down glacial moraines paved with cobblestones and sparsely covered with sage, fourwing saltbush, chamiza, yucca, and pinyon. [1] By the river itself is a more riparian environment featuring cottonwoods and willows.

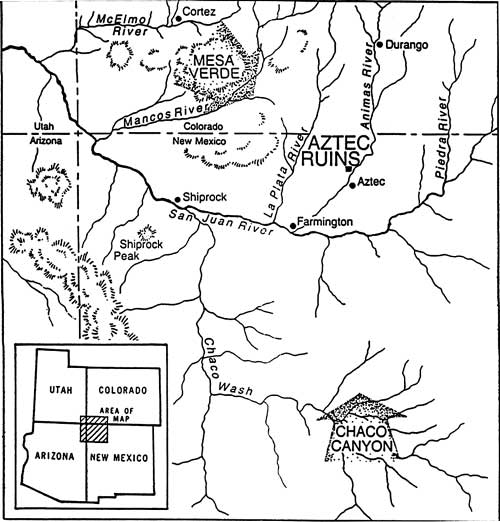

The terraces and bottom lands along this lower route, at an elevation more than a mile high, once witnessed the rise, evolution, and disappearance of a unique Native American civilization (see Figure 1.1). In spite of a century of unmitigated Euro-American impact, signs of this civilization still pepper the terrain. As the Animas swings westward to merge into the larger San Juan River, most prominent among the remains is a complex of some 13 distinct constructions located approximately 400 yards to the west of the river's northwestern bank, now collectively known as the Aztec Ruins. [2] This grouping once likely functioned as an administrative, trade, and ceremonial hub for numerous smaller, contemporaneous, satellite communities scattered about the gravelly uplands and valley floor and may have represented them in the broader organization structure archeologists now term the Chaco Phenomenon. Modern research has determined that, for unknown reasons, all the settlements, large and small, were deserted before A.D. 1300.

|

| Figure 1.1. Map showing location of Aztec Ruins between the Mesa Verde region to the northwest and Chaco Canyon to the south. |

Several categories of artifacts taken from the largest ruin suggest the possibility of sporadic usage of the abandoned structure by some protohistoric Native Americans. Nomadic peoples later moving in to fill the void left by departing sedentary town dwellers generally paid the emptied old houses little heed, as they slowly slumped back to earth and vanished from the common memory. However, among examples of a possible post-abandonment Indian presence are the bones of a baby strapped to a cradle board. A ranger found them in 1945 when cleaning weeds and dirt off the extreme southwest corner of the courtyard of the largest settlement. A multiple burial there just barely covered by earth contained an adult accompanied by prehistoric pottery in addition to the infant. Ethnologist Leslie Spier identified the cradle board as either Ute, Northern Pueblo, or possibly a combination of traits of the two. [3] Recent catalogers recognized as more recent than the ruins themselves a few potsherds that might be of Pueblo IV time or of Ute manufacture and a finely tanned leather bag that appears of Ute origin. [4]

SPANISH KNOWLEDGE OF THE RUINS

Had the men of Spain's most northerly seventeenth-century colony of Nueva Mejico named these ruins, one could rationalize it as an illogical but understandable transfer of known experience to the unknown and take the name as evidence that the Spaniards had been the first non-Indians on the site. The Aztec Indians were 1,500 miles away in the central Mexican highlands from which the borderland Spanish colonists had moved but undoubtedly to them were the prototypical natives. The Spaniards would not have known that the Aztecs had not emerged as a cultural entity until long after the Animas houses had been deserted. However, it was later settlers and explorers from the United States rather than the colonial Spaniards who were responsible for the designation of Aztec Ruins.

Regardless of the inappropriate modern name, details of Spanish soldiers in pursuit of marauding Native Americans must have spotted some of the Animas valley ruins and passed their observations along by word of mouth. Random traces of Spanish parties have been found in the vicinity. These include Spanish bridle bits, hand-hammered bridle ornaments of bronze, and more than 125 armor scales recovered in the late 1930s in Hart Canyon and near Hampton Arroyo, short distances northeast and due east from Aztec Ruins. [5] A copper pot owned by Scott Morris was reclaimed from the surface of Aztec Ruins in 1877. It was theorized to have been discarded by a wandering Spaniard, who may have spent the night in the protection of the structure. Modern analysis shows it to be of mid-nineteenth-century workmanship and more likely to represent littering by an early Euro-American settler. [6]

There must have been some bank of oral history behind the report of October 26, 1777, to the King of Spain made by the military cartographer for the Escalante-Dominguez expedition, Miera y Pacheco. He wrote that a presidio and settlement of families should be founded near the junction of the San Juan and Animas rivers, where beautiful meadow land was suitable for agriculture and pasture. He noted ancient buildings and irrigation canals in the meadows. [7]

The Miera y Pacheco reference is thought to have been to a large cobblestone village called the Old Fort situated at the confluence of the Animas and San Juan rivers and other settlements in the area, but probably not including Aztec Ruins. Earl Morris, excavator of the main Aztec Ruin, believed they may have been sighted. [8] Regardless, the information must have been second-hand since the expedition crossed this stretch of the terra incognita at least 40 miles to the north.

A second indication that Spaniards knew of the Animas River appeared in the journal of Antonio Armijo, leader of a 60-man Mexican expedition from Santa Fe to Upper California, which stated that on November 17, 1829, his command arrived at the banks of the river. If these men made the first sighting of Aztec Ruins, Armijo failed to mention it. [9] From lack of documentation, it can only be assumed that the Spaniards were either unaware of or not impressed with the specific grouping of Aztec Ruins.

EURO-AMERICANS BECOME ACQUAINTED WITH THE RUINS

The association of the ruins on the Animas with the Aztec Indians was made by early American settlers. With the northern Hispanic frontier relatively unpatrolled in the early nineteenth century, mountainmen quite surely worked their way from the Rocky Mountain hunting grounds south along the perennial waters flowing toward the Colorado River. One of these was the Animas. Although the wanderers may have paused to wonder at jagged high walls of shaped stone standing like enormous fins above huge piles of accumulated detritus, they were not inclined to write of their impressions. But among themselves they likely spoke of the silent wrecked structures as the Aztec houses. In that, they were reflecting a widespread popular impression inspired by a book of 1844, History of the Conquest of Mexico by William H. Prescott, that the Aztecs believed they had originated in some vague "north land." To persons on this part of the northern borderlands, the many derelict walls and the potsherds and other artifacts strewn around them confirmed that the Aztecs indeed had passed through the northern Southwest on their way to central Mexico.

The scientific community was more cautious in suggesting any genetic relationship between the regional prehistoric population and that of central Mexico. Hence, the first known eyewitness account of Aztec Ruins, written in 1859 by geologist John S. Newberry working for the Corps of Topographical Engineers of the U.S. Army, omits any such conjecture. Instead, Newberry's report contains a perceptive account of the lower Animas natural and cultural environment and correctly attributes the prehistoric remains to the forebears of the modern Pueblo Indians. He described the ruins as being constructed of yellow Cretaceous sandstone masonry, with some exterior walls standing 25 feet high and interior walls retaining plaster. Associated mounds resulting from collapse of subordinate structures, together with the main pueblos, indicated a large indigenous population formerly living in the valley. [10]

This assessment notwithstanding, the frontiersmen still seemed to have felt that local prehistory was somehow linked to the Aztec tribe of the Spanish conquest era. A letter written in 1861 by a citizen of Animas City, Colorado, clearly reveals this attitude when he noted, "The valleys of the Rio de las Animas and San Juan are strewn with the cities, many of them of solid masonry. Stone buildings three stories high are yet standing, of Aztec architecture. An immense and prosperous population has at some former period resided here and but a few localities are capable of sustaining a more numerous one." [11]

A few years later, a similar account reinforced the supposed Aztec connection. Appearing a century after mapper Miera y Pacheco described the same site for the benefit of the Spanish monarch, the author of this account stated that some Aztec antiquities from near the mouth of the Animas River had been displayed at the Denver Exposition. Included among them were human remains showing characteristics of what were called "semi-barbaric races" and Aztec pottery, stone tools and parchment(?). [12]

Sixteen years after Newberry's inspection of Aztec Ruins, a second geologist explored the mounds and duly reported his findings. He was Frederic M. Endlich, attached to the Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, better known as the Hayden Survey. Endlich's remarks provide important details about the site 41 years prior to any formal archeological exploration. Noting many small dwellings of mud and cobblestones about the Animas valley, what he interpreted as watch towers on cliffs above, and the large sandstone edifice in a central bottom-land location, Endlich imagined an aboriginal city. In his view, the multistoried, multiroomed community at the center of settlement could have been a refuge in case of invasion for those living in the outlying houses. For that reason, he named the major site Acropolis. He said it was laid out in a squared-horseshoe arrangement opening to the south, with perhaps as many as 500 rooms. The small room dimensions provided suggest he may have found a way into ground-level chambers of the easternmost mound at the Aztec Ruins complex. Those in the west mound are larger. Some units had intact ceilings of wood and plaster. Rectangular doorways were typical, but many chambers had no other openings. Although the carefully executed plan of the building and its skillful construction suggested Spanish workmanship, no evidence for the use of metal tools in its erection made its building by aborigines probable. Artifacts observed were arrowheads, debitage resulting from implement manufacture, potsherds, and a single metate. Sections of irrigation ditches were seen near the ruins. [13]

The first trained anthropologist to view the largest of the Animas valley mounds was Lewis H. Morgan, whose principal research was among eastern Woodland tribes rather than those of the Southwest. Morgan spent the summer day of July 22, 1878, making a drawing of the house plan of the westernmost structure and taking notes about it. These were published the following year. [14] Nonetheless, the Morgan work at Aztec was a dead-end effort because no following research was forthcoming.

The identification of the many obvious evidences of former occupation with the Mexican Indians became locally accepted as fact. [15] When settlers began arriving in the Animas valley about 1876, it was inevitable that through frequent repetition the largest concentration of these sites customarily was referred to as the Aztec Ruins. Even though most other regional sites also were called Aztec, the name stuck. [16] If known, the Endlich name of Acropolis doubtless would have been ignored.

One of the first settlers on the lower Animas was John A. Koontz. He served in the first Colorado legislature but moved along with the expanding frontier. Koontz opened a general merchandise store to meet the needs of his neighbors but also acquired two important pieces of land. One was a homestead, 40 acres of which were sold as a townsite to replace the original post office on private land a half mile up the valley. Because of the proximity of the landmark ruins, the former name of Wallace was dropped in favor of Aztec.

The second piece of Koontz property, acquired on November 28, 1890, by a patent issued under the Desert Land Act, was a 160-acre plot at the foot of the west terrace upon the lower slope of which stood the ruin mounds. A photocopy of the legal document shows that 20 acres in the northwest corner of the tract consisted of boulder hills that were not suitable for agricultural development. [17] Koontz sensed the importance of the prehistoric remains, which were surrounded by arable land. He put a stop to the practice of using the ruins as a source for construction materials but continued to permit local families to go there for outings. Many early day picnickers had their pictures taken while standing on top of the highest walls (see Figures 1.2 and 1.3). [18]

|

| Figure 1.2. West Ruin, ca. 1880. (Courtesy Aztec City Museum). |

|

| Figure 1.3. East Ruin, ca. 1880. (Courtesy Aztec City Museum). |

The settlers' children first explored the interior of one of the Aztec Ruins mounds. In the winter of 1881-82, a group of boys and their teacher broke through the ceiling of a first-story room in the northwest corner of what appeared to be the largest compound. They knocked holes in the stone walls of a series of similar adjoining rooms by which they gained access to ancient dusty quarters that had not been entered for 600 years or more. [19] In two of these dark, stagnant, masonry cells, they were thrilled and doubtless frightened to encounter desiccated remains of 15 humans and a rich assortment of artifacts that had been left with them. These objects were removed from the rooms, taken home to be shown to curious parents, and then over the years dissipated -- their value to science lost forever.

A decade later, preparations for the Chicago Worlds Fair greatly stimulated interest in the antiquities of the Four Corners area. A huge replica of a cliff with a full-size model of a prehistoric dwelling featured finds from Mesa Verde. To expand on that exhibit, Warren K. Moorehead, a teacher at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, was sent with an 11-man team to spend four months exploring the San Juan drainage. The party camped for nearly two weeks on the banks of the Animas while the crew made notes, ground plans, and sketches of the Aztec Ruins complex. A brief account of this work appeared shortly after the men returned to the East, but a more detailed report did not circulate until 1908. This report remained the longest article on the ruins until excavations commenced eight years later. [20]

The same year that Moorehead finally published his paper, Henry Dudley Abrams, proprietor of a hardware store in the village of Aztec, by warranty deed acquired the Koontz property on the west side of the Animas. A half-share water right in the Farmers Ditch was included in the transfer of property. [21] As much of the land as possible was cleared and put under cultivation or converted to pasture for livestock, leaving hillocks of dilapidated aboriginal masonry and the thorny overgrowth that engulfed it looming above the fields like islands in a sea.

Private ownership of the ruins did not protect them from some vandalization. Abrams tried to prevent damage to the major houses, but thousands of initials carved or scratched into wooden lintels and ceiling beams show that he was not successful. Perhaps valley residents who made pleasure excursions to the ruins amused themselves in this way. [22] One told of a cow falling through a decayed roof of a multistoried unit and becoming trapped in a lower room. Whether any damage to the building resulted is unknown. Abrams himself was responsible for some dispersement of weathered timbers from the principal mound. On one occasion, he donated wood from them to be used for the "Chair of the East" in a fraternal order of which he was a member. [23] Nor did his conservation efforts extend beyond the big mounds. He leveled a small house 150 yards to the north of the largest ruin, and he converted several rooms of the Hubbard Mound, an unusual construction several hundred yards north of the most prominent mound, into a root cellar. A second root cellar was constructed into Mound F between the two major settlement mounds. Exactly how many other sites were disturbed or their specific locations cannot be determined now. Furthermore, tenants on the Abrams farm engaged in some illicit salvaging of loose specimens. According to William H. Knowlton, he and his father dug up three burials exposed by a plow and sold them to the Smithsonian Institution for $25 apiece. [24]

Generally speaking, however, by the early twentieth century the ruins were simply a local curiosity in which few people had little more than passing interest. That lack of interest helped hold them in trust for the future.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006