|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 2: EARL HALSTEAD MORRIS AND THE AZTEC RUINS

Few Southwestern archeological sites are more identified with a single individual than is Aztec Ruins with Earl Halstead Morris. He first came there in 1895 as a child of six and later remembered the exact room (West Ruin, Room 1212) which he and his father had entered. He recalled his astonishment at the human bones they saw stretched out on an adobe platform raised above the floor. [1] As a youth, with shovel over shoulder and trowel in hip pocket, he dug in many of the valley's antiquities in search for pieces of pottery. Just out of college, he persuaded one of the most prestigious institutions in the nation, the American Museum of Natural History, to undertake the excavation of the largest of the Aztec Ruins and to put him in charge of a proposed five-year program there. In the process, he established an enviable scientific reputation in regional archeology and was granted the right to live adjacent to the site in a house he constructed using some reclaimed twelfth-century materials from the ruins. After the National Park Service took over ownership of the property, he served for a time as its first custodian. Later, he rebuilt its major ceremonial edifice, a Great Kiva, which simultaneously became a monument to the aboriginal builders and to his own insight and ingenuity. And at the end, one summer dawn in 1957 his ashes were spread into the cushioning earthen floor of an inner room. To know Aztec Ruins, one necessarily must also know something about this man who was so intimately associated with the place for more than 60 years and whose work is essentially what today's visitor sees in the monument.

Ettie (Juliette Amanda Halstead) and Scott N. Morris of upper New York state were among the throng of adventuresome persons drawn west in 1879 by the gold rush at Leadville, Colorado. After mining activity slowed, Scott found employment in regional sawmills and construction camps and in freighting goods to them. Ettie taught school wherever her husband happened to be working. In 1889, their only child, a son, was born in Chama, New Mexico, where Scott then clerked in a drugstore.

The year before Earl Morris's birth, Southwestern archeology was launched with the discovery of two spectacular cliff houses on the Mesa Verde of Colorado -- Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House. It is likely the ruins had been seen earlier by wandering white miners or trappers who failed to publicize the find. [2] By the time Morris was 10 years old, several hundred other cliff-side and mesa-top ruins were known and identified as Anasazi, or Old Pueblo. An earlier culture (Basketmaker) was unearthed in caves of southeastern Utah. Most important was a four-year program that cleaned out a portion of the huge structure of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon to the south of the San Juan Basin. Every exploration seemed to support the notion that at some unknown time ancestors to the modern Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande and Zuni valleys and the Hopi mesas once lived on the Colorado Plateau. These exciting finds might have passed unnoticed by the small Morris lad, except for his father.

During the 1890s, Scott Morris joined the ranks of a dozen Farmington, New Mexico, men in prospecting for prehistoric artifacts as a means of supplementing their incomes. There were no federal laws prohibiting this activity on public lands. Those persons developing farms welcomed diggers as a way to get rid of the nuisance of heaps of fallen stone walls in their tracts. Since the vicinity of Farmington formerly supported a large, now absent, Indian population, the pickings were good. Scott sold several collections for nominal sums. The search for specimens became an enjoyable pastime for him and his young son. On every possible occasion, they hitched a team of horses to a wagon and took off exploring the back reaches of northern New Mexico. In later years, Morris credited his father with having given him an invaluable working knowledge of practical mechanics and earth moving. His companionship with his father also imparted a lifelong passion for the quest of artifacts and introduced him to a site that eventually was to be a personal memorial.

Scott's murder when Earl was 14 years old intensified the boy's interest in his pothunting avocation. Young Morris spent even more of his spare time after that tragedy seeking out signs of what he called the Old People. In compensating for the loss of a dear parent, Morris was at the same time building an unrivaled fund of field experience concerning how and where to dig. [3] He often fantasized about excavating the largest of all the ancient remains in the vicinity, the Aztec Ruins.

Ettie Morris saw to it that, when the time came, her son attended the University of Colorado. To make that possible, she tutored youngsters in her home. Earl pitched in by chopping wood to earn tuition money. At the university, he achieved the education and maturity to transform outright pothunting into an earnest search for knowledge. As he later observed in a biographical sketch: "When I came in contact with those who gave me the scientific point of view, it served as a key to a previously sealed book which enabled me to put in order the fund of information gleaned from my boyhood pothunting." [4]

Earl Morris's involvement with work at Aztec Ruins came obliquely through an association with some amateur archeologists from St. Louis. One was John Max Wulfing, importer and wholesale grocer, who bought a pottery collection from Morris gathered from the La Plata district north of Farmington. That stimulated Wulfing to join with David L. Bushnell, owner of a seed store, and George S. Mephan, operator of a chemical dye plant, in bringing some guests west to Aztec for an archeological holiday during the summer of 1915. The party stayed in a local hotel so as not to inconvenience the ladies with tenting. Morris arranged with an Animas valley settler for the exploration of a 39-room pueblo on his land located about three-eighths of a mile northeast of Aztec Ruins. There the neophyte archeologists were instructed in the fine art of digging. Morris cleared the site prior to their arrival so that the "riches" could be exhumed with little physical exertion. Among tangible rewards for the Middle Westerners to take home were 40 complete pottery vessels. Some were burial offerings placed next to the dead beneath house floors. Morris apologized that the artifact returns were limited because the site had been probed earlier by others. [5] Even so, the enthusiasm of the visitors convinced him that they might support more serious excavations in the area.

Earlier that summer, a stroke of luck put Morris under the guidance of Nels C. Nelson. Nelson was an internationally recognized scholar on the staff of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. His career previously centered on European prehistory and the use of stratigraphic analyses to determine relative chronological positions of cultures as they evolved over long periods of time. In 1915, Nelson hoped through work in New Mexico to demonstrate the value of such methods in studying the briefer American prehistory. A personal relationship between the director of the museum at the University of Colorado and the curator of anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History led to selection of Morris to be his field assistant.

A second lucky happenstance was that in 1915 Nelson was asked to locate a suitable classic Pueblo site to be excavated by the American Museum of Natural History under the patronage of Archer M. Huntington. Huntington, heir to the Southern Pacific Railroad fortune, was a generous contributor to the museum's research in the Southwest. Upon learning of this, Morris seized his golden opportunity. He persuaded Nelson to come to Aztec Ruins at the end of the digging season to see for himself the possibilities they afforded. "By coming to my camp," he wrote Nelson, "you would have the opportunity to examine the great pueblos and to familiarize yourself with the culture of this immediate vicinity more easily and more satisfactorily than would be possible if you were to make only a brief stop at Aztec." [6] The museum already had an enviable Anasazi collection from Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon as a result of the Hyde Exploring Expedition during the late nineteenth century. The observable architectural and ceramic remains at Aztec Ruins appeared to be another manifestation of that Chaco culture. They would help further elucidate the prehistory of the eastern San Juan Basin. Nelson was sufficiently impressed with what he saw of the size and relative lack of vandalism that he assured Morris he would recommend prompt excavation of the Aztec Ruins.

Discouraged over following months of no word from the American Museum, in February, 1916, Morris contacted Wulfing. He suggested that the Missouri Historical Society, of which Wulfing and his friends were members, sponsor excavation of Aztec Ruins. Morris estimated that the job of clearing what he believed to be the largest of the mounds could be done for $7,500. As a lure, he called Wulfing's attention to the 7,000 pieces of turquoise and large numbers of earthenware pots recovered at Pueblo Bonito by the Hyde Expedition. To further press his case, and to play on the current desire on the part of professionals and public alike to amass objects, Morris persuasively wrote Wulfing, "I do not hesitate to say that the excavation of the Aztec Ruins would yield a larger and better collection than has ever been taken from one site in the Southwest." [7]

Meanwhile, to prepare for the possible acceptance of his proposal, Morris approached landowner Abrams. He explained, "I am drafting plans to put before the St. Louis people for the excavation of the largest ruin, and I wish to ask if you would grant them the right to excavate upon the terms which were extended to the Phillips Academy [the Moorehead party of 1892]. If the plans are received with any favor at all, I shall go to St. Louis to endeavor to clinch the deal." [8]

At the time these negotiations were going on, an agent of the American Museum was in Aztec to confer with Abrams about an excavation concession. Abrams, however, had no knowledge of the museum. Immediately he got in touch with Morris, the only trained archeologist he knew, to find out if the American Museum were a reputable institution. [9] Indeed it was, Morris replied. At the same time, Morris made subtle inquiries of Abrams regarding his own possible future role in the project. [10] He yearned for the assignment but did not want to appear too eager.

Within the next six weeks, the enduring identification of Morris with Aztec Ruins was assured. In April, Abrams granted the American Museum permission to proceed with its proposed endeavor. Meantime, the Missouri Historical Society withdrew from the picture. The American Museum hired Morris to serve as its field supervisor at a salary of $100 a month and expenses. Abrams directly notified Morris of his decision to allow work to go forward and, as a good father looking out for his children, added, "...the boys [of which there were three] may want to do some of this." [11]

The president of the University of Colorado knew Morris as a museum assistant at that institution and gave him a glowing recommendation. He remarked to Clark Wissler, curator of anthropology at the American Museum and administrator of the Southwestern archeological programs, "I told Morris before he left for the field that I felt you were offering him a very great opportunity to show what he is worth, and I know he intends, if the arrangement is consummated, to throw himself into the work with all the vigor he has. The more I see of the quality of the man the more favorably I am impressed." [12]

At last, Morris's childhood dream seemed about to materialize. Enthusiastically, within days he sent the museum estimates of costs to include a modern photographic kit and a plan of operation. Graciously he said, "To excavate the `Aztec Ruins' is a dream which has endured from my boyhood, and I wish to express my appreciation of the fact that you see fit to give me a part in it." [13]

Prior to beginning the Aztec work, Morris met Nelson at Chaco Canyon. The 65 miles from Aztec was then a six-day wagon trek or three days by automobile. Together, the men fruitlessly trenched what they regarded as a great trash heap at the southern front of Pueblo Bonito in hopes of finding stratified deposits and, in the process, expended one-third of the year's appropriation for Aztec.

Back on the Animas in late July, Morris and Nelson immediately initiated work there by hiring a crew. An early frost had ruined the season's fruit crop, making the $2.00-per-day wages attractive to a number of local farmers. [14] A consequence of their employment was that excavation of the ruins was viewed as a community effort. Like Morris, most of the crew at one time or another had prowled the regional sites. They were familiar with the constructions and the general range of imperishable artifacts to be expected from them. Moreover, the men had a proprietary curiosity about this greatest monumental pile that long had been a fixture on their horizon. Under Morris's tutelage, many became first-class, reliable diggers who continued to work for him in Aztec and elsewhere. They, in return, taught Morris a number of handy man skills.

Excavation of the Aztec Ruin had a significant impact on a few of those hired in the opening season. One whose life was altered was Oscar Tatman, owner of a poultry farm and apple orchard south of the ruins. Through many years of association with Morris, Tatman gained a fund of practical archeological and ruin-repair knowledge that qualified him to be hired as caretaker and guide at Aztec Ruin on occasions when Morris was away. Oley Owens was another local farmer supplementing his income at these and other digs. [15] Sherman Howe, raised on a farm just across the Animas River from Aztec Ruin, was one of the schoolboys who broke into the North Wing rooms in 1881. [16] He felt a special enjoyment at being part of the excavation team and later blossomed as a well-informed volunteer guide. During the lean Depression years, when he was fearful of losing his farm, he was especially grateful to be employed on the restoration of the Great Kiva. Finally, as a parting gift to the place he had known all his life, Howe donated a personal artifact collection gathered through years of pothunting about the valley. [17] Jack Lavery, in addition to being a fair carpenter and blacksmith, was an expert mason. "Prehistoric Grandfather," as the Zuni Indians working along side him in Chaco Canyon knew him, was critical to the task at hand at Aztec Ruin. Morris acknowledged that more than half the repair work accomplished at the site during his association with it was done by Lavery. [18]

The years from 1916 to 1922, when Morris was most active in the exploration and interpretation of Aztec Ruin, represented a learning period in the new discipline of Southwestern archeology. Morris and his crew had to experiment with basic procedural and preservation techniques. Aztec Ruin also became a testing ground for new intellectual concepts that determined the future course of Southwestern prehistoric studies. Tree-ring dating, stratigraphically-controlled digging, and comparative architectural and ceramic analyses undertaken at Aztec Ruin became part of the fund of archeological skills applicable to the entire gamut of Anasazi sites. Interpretation of the prehistorical progression made possible through these diverse avenues was constantly reevaluated as the database expanded. To Morris's credit, he kept pace with the science as it evolved in his time.

Near the end of the Aztec project, Morris's activities expanded beyond mere digging and reporting on the site. He erected a small, unobtrusive house in front of the exposed western house block for himself and his mother (see Figure 2.1). He also served as the on-site museum agent in the purchase and transfer to the federal government of the ruins and surrounding land.

|

| Figure 2.1. Earl Halstead Morris in front of the house he built adjacent to Aztec Ruin, ca. 1920. (Courtesy University of Colorado Museum). |

With the American Museum funds for work at Aztec Ruin depleted in the early 1920s, Morris turned to related research across the vast sweeps of the Colorado Plateau. Earlier, he purchased a Model T Ford of 1917 vintage for $104.95. He loaded the open-sided touring car with extra gas and food, a bedroll, water bags, cooking gear, pitch-covered floor boards that could substitute as fire wood in barren wastes, and a kit of tools and a shovel to keep the vehicle operating over virgin terrain. As son of a rough-and-ready frontiersman, he relished such adventure. Slowly Morris tracked down widely scattered and unknown traces of the ancients, from the rugged slick rock ledges bordering the Colorado River to the craggy Lukachukais separating New Mexico and Arizona. From 1923 to 1929, he explored caves sheltered within the inner recesses of Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, where he found structures and deep trash deposits spanning a millennium of human presence. [19] He dug sites representing several stages of Anasazi development in the mountains south of the San Juan and near the massive igneous spire of Bennett Peak at their eastern flanks. Often, he returned to clusters of house remains piled along the mesas bounding the La Plata River, which he had explored with his childhood shovel. Throughout all these excursions, he was constantly on the alert for tree-ring samples to help fill gaps in the temporal chronology being established by tree-ring scholar Andrew E. Douglass.

As more or less a footnote to his preferred areas of concentration, for five winter seasons during the 1920s, Morris also worked for the Carnegie Institution of Washington in excavations and repair of the huge Maya site of Chichen Itza on the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico.

During the 1930s, Morris was called upon for important undertakings, which reinforced and enhanced the cultural heritage of three Southwestern national parks or monuments. This came about because he was known for having a unique combination of archeological and engineering expertise. Morris secured the Mummy Cave tower in Canyon del Muerto, Arizona, and the multistoried tower in Cliff Place in Mesa Verde, Colorado. Both structures were precariously cracked and likely to come cascading down the canyon talus if not soon repaired. He threw up wing dams to keep lower units of White House, Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, from being washed away. Probably the project with which he was most emotionally involved was the restoration of the Great Kiva at Aztec Ruin to demonstrate to modern observers both the architectural abilities and the religious base of the Anasazi. More than 50 years later, these monuments endure for the benefit of future generations.

Toward the end of the decade of the 1930s, Morris's active field work came to a triumphant end. The significant excavation of a Basketmaker village north of Durango, Colorado, took the human drama as it had been played out in the northern Southwest back to days before the Christian Era. Attainment of these dates was to Morris the culmination of a 20-year hunt for wood samples that provided a scaffold of time for the cultural evolution of the Anasazi. Having supplied examples of the last-gasp era as represented at Aztec Ruin, it was only fitting that he also supplied those defining the beginning.

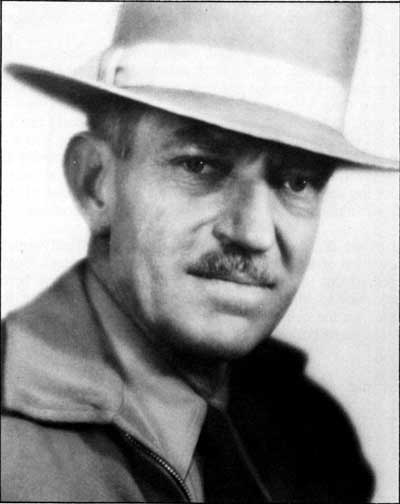

The final sixteen years of Morris's life were spent in the work room of his home in Boulder, Colorado, and basking in honors bestowed upon him for his lifetime dedication to unraveling Southwestern prehistory. He completed a series of technical reports resulting from the prodigious gathering of raw data. Patiently he advised younger men coming up through the ranks and responded to their questions about the opening of Aztec Ruin. He contributed an assortment of well-worn hand tools for a museum display at the monument, and he sent a photograph of himself (see Figure 2.2).

|

| Figure 2.2. Earl Halstead Morris, ca. 1950. |

At age 67, death took Morris back to the place where his notable career began. His ashes were distributed by Homer Hastings, monument superintendent, within a portion of the Aztec Ruin which Morris had cleared exactly 40 years before. A decade later, the precise location of the burial could not be positively identified. [20] A bronze plaque noting his contributions was installed in the part of the visitor center at Aztec Ruins built by him as the Morris home. The excavator of the principal attraction at the monument, the West Ruin, had indeed become one with the great house and its long-departed inhabitants.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006