|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 3: PEELING AWAY PREHISTORY

1916: EXPLORATORY SEASON

In April 1916, Henry D. Abrams, owner of the land encompassing the major Aztec Ruins, formally agreed to allow the American Museum of Natural History to conduct excavations on a 40-acre section of his farm surrounding the ruins (see Appendix C). The museum chose to work on the largest of the sites. Since this was the era when patronage by wealthy individuals was prerequisite to expensive research, John P. Morgan donated $2,000 for the initial 1916 exploratory season. [1] After it was demonstrated to be a worthy undertaking, the project became part of the larger Archer M. Huntington Survey of the Southwest. A local newspaper mistakenly reported that the explorations were sponsored by the New York School of Archaeology. [2] Such an institution is not known to have existed.

The highly acclaimed American Museum of Natural History assigned the demanding task of uncovering the huge site of Aztec Ruin, with its potential significance to interpretation of regional prehistory, to Earl Morris. He was then a young man just out of college, who had notable digging experience but remained untested intellectually. The museum's decision reflects the scientific naivete of the early twentieth century. On the one hand, the museum expected Morris to direct a large untrained crew in gross earth removal and in delicate specimen retrieval. On the other hand, it assumed he would care for artifacts, catalogue them, keep a field and photographic log, attempt to reconstruct past human events from a silent incomplete record of discarded material goods, and eventually publish an appraisal suitable for both the benefit of the scientific community and for the interested public. The laymen demanded special consideration because some of them might fund similar museum endeavors. In addition, complete clearing and repair of the West Ruin, as the largest mound became known, was to be a corollary aspect of the total project. Clark Wissler, director of the museum's archeological programs, estimated that the effort would take five seasons of field work and cost about $10,000. Both figures subsequently proved unrealistic. The enormity of this challenge shrank before the vast self-confidence of this one frontier-bred researcher. Neither Morris nor his directors yet comprehended the inherent technical and cultural complexities, which today would engage the services of a dozen specialists and a large contingent of specially trained excavators and construction workers.

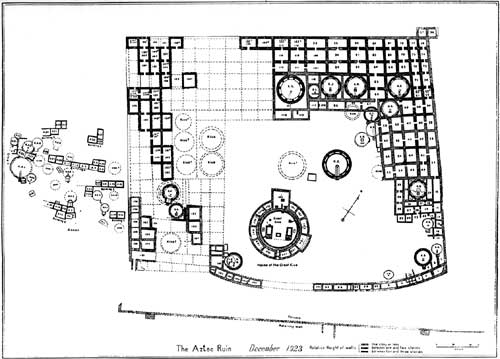

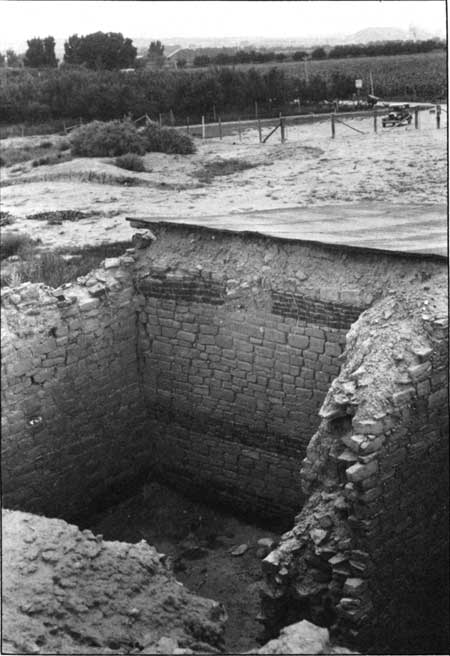

The first phase of the Aztec Ruin project was clearing the ruins of their nearly impenetrable covering of prickly vegetation in order to ascertain their dimensions. [3] Several trails snaked through the overgrowth to potholes opened by earlier explorers. Once all the tall obscuring brush was hacked and burned, three long high mounds left from deterioration of the east, west, and north arms of an edifice were exposed. A heap of cobbles several feet high suggested an arc of one-story rooms enclosing the south side of the pueblo. The settlement plan was a very large, multiroomed, rectangular building wrapped around an open courtyard. [4] The West Wing stood 20 feet high, the opposite East Wing only five feet at its lowest southern end, but the north side of the compound was more than 29 feet high and appeared to have stood three stories (see Figure 3.1). [5] The compound was placed on a leveled terrace that gently dipped southward. The remains of an enclosing southern village wall of sandstone backed by cobblestones approximately four and one-half feet high was reinforced by abutments at the east and west ends. Low steps gave access through the wall to the plaza.

|

| Figure 3.1. West Ruin after being cleared at the beginning of the field season of 1916. |

To quickly obtain specimens, Morris proposed to begin work at the West Ruin with trenching the refuse mound lying off the southeastern corner of the structure. He realized that to museum patrons, expedition success often was linked to the number of artifacts recovered. Trash heaps and the burials they sometimes sheltered frequently produced those things. Another consideration was that the refuse mound might be covered by the waste of later work. [6] Morris wrote Wissler, "Relatively few graves have been found in the immediate neighborhood of the pueblos, and beyond doubt in the low mounds to which I refer, there will be a great number of them together with much pottery." [7] The museum recognized the patron appetite for tangible returns. As a curator later commented, "There are a great many people who get more enthusiastic over nice specimens than they do over the solution of problems. We, naturally, like to please every one." [8] Nevertheless, the museum staff vetoed Morris's proposal.

In July, expedition work began at the southeastern corner of the West Ruin house complex itself. Morris probably was disappointed that his pothunting instincts were held in check while Nelson undertook to trench the seven-foot-deep deposits of the southeast refuse dump. Nelson hoped to establish a relevant chronology through stratigraphic analysis, wherein older materials, if undisturbed, were beneath more recent deposits. In this, he was disappointed.

Outfitting the project was simplified because no field camp was set up. Abrams offered the area of his farm located under some cottonwoods, but instead the dozen hired diggers went home at night. All that Morris had to acquire were hand tools, such as shovels, picks, mattocks, trowels, and axes; wheelbarrows to transport spoil dirt; and cement for anticipated repair work. He delayed erecting a planned 15-by-30-foot frame shed in the plaza to provide storage for equipment and recovered artifacts.

In the formative period of Southwestern studies, there were no uniform guidelines for excavation, curation, or documentation procedures. Scientists working at Pecos, Puye, Mesa Verde, and in northeastern Arizona in 1916 were going about their explorations and recordation of data in their own ways with little or no consultation with each other regarding methodological or taxonomic standardization. Consequently, Morris had to rely on his personal previous experience in the Animas area to begin exposing Aztec Ruin. He devised his own phased excavation plan, cataloging system, and preservation techniques. The southeast corner of the site offered the easiest spot for training the crew. Its relatively low profile could be cut away with the least amount of time and effort. Later research indicated that it likely was a sector of the village where human occupation preceding the above-ground remains might have been identified had procedures been more refined. If such remains were present, they were destroyed or overlooked because of unfamiliarity with them.

Morris was aware of some of the weaknesses of his beginning efforts. He later commented, "The excavation at the south end of the east wing was done at the first season's explorations. Doubtless had a search been made of it, the last level of occupation might readily have been identified and used as a base plane. Instead the level followed was that of the field to the eastward." [9] The field, of course, had been plowed and was no longer representative of the aboriginal landscape. Even though the museum's instructions to Morris were to uncover the classic pueblo, the scientific staff expressed interest in a broader scope of inquiry than its man in the field accomplished. [10]

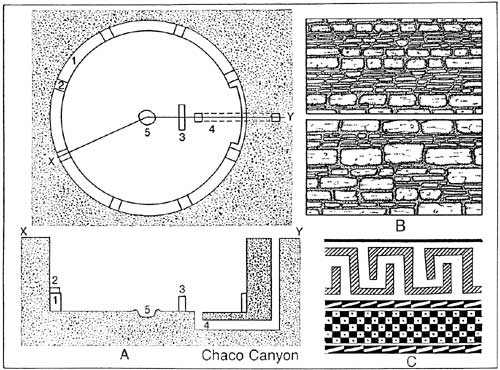

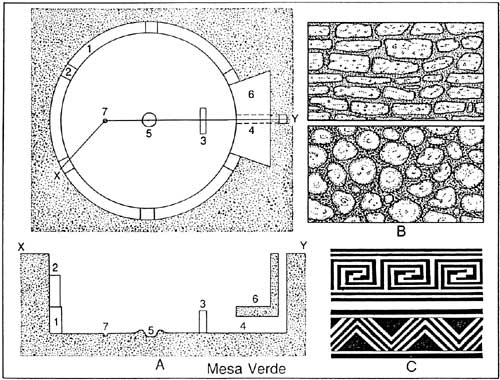

Earlier researchers pinpointed three major centers of prehistoric development on the Colorado Plateau sharing a widespread homogeneity of culture but with certain regional characteristics. Anasazi living in the Kayenta district of northeastern Arizona differed in some aspects of their material culture from those in the Mesa Verde domain. Both these groups evolved in ways that were compatible to, yet distinctive from, those of the Anasazi living in Chaco Canyon. All three branches shared an architectural mode for communal living, but construction methods and quality of workmanship differed (see Figures 3.2 and 3.3). Among lesser handicrafts, pottery was an especially useful diagnostic element of the material culture for students of the Anasazi past. It was the most abundant kind of portable artifact in most sites. All Anasazi used the same fundamental ceramic technologies, but some raw resources, vessel shapes, and decorative styles produced end products that became hallmarks of particular regions.

|

| Figure 3.2. Chaco cultural traits present at Aztec Ruins. A) Plan and profile of typical kiva: 1, bench; 2, low pilaster; 3, deflector; 4, ventilator shaft; and 5, firepit. B) masonry types. C) pottery designs. (After Lister and Lister, 1987: 89). |

|

| Figure 3.3. Mesa Verde cultural traits present at Aztec Ruins. A) Plan and profile of typical kiva: 1, bench; 2, high pilaster; 3, deflector; 4, ventilator shaft; 5, firepit; 6, southern recess; and 7, sipapu. B) masonry types. C) pottery designs. (After Lister and Lister, 1987: 96). |

Despite these relatively minor regional differences among the Anasazi as a whole, archeologists assumed that the three branches somehow had marched in unison through time. There was no means of dating Southwestern antiquities to verify or reject such a premise. Therefore, students of the Anasazi held the simplistic view that identifiable culture variances from enclave to enclave across the greater expanse of the Colorado Plateau provided the means for placing individual sites and their former inhabitants within an areal developmental framework that everywhere was at the same level of advancement at any given period. In 1916, the period with which most of the scientists were dealing was that culminating a cultural continuum of unknown duration. That was the period of Aztec Ruin.

Basing his judgment on these kinds of distinctions among groups of otherwise identical Anasazi, prior to excavation Morris felt that some observable elements at Aztec Ruin suggested either a local cultural hybridization between Chacoan and Mesa Verdian branches of the Anasazi or their contemporaneous sharing of the village. In either case, that sort of site utilization would have been unusual. To Morris, sandstone masonry remnants poking above the crust of the mounds and the configuration of the town plan were unquestionably of Chacoan derivation. However, the cobblestone southern enclosure was out of pattern for usual Chaco constructions. It also was not typically Mesa Verdian, but similar prehistoric houses in the vicinity contained what Morris believed to be Mesa Verdian trash. This was particularly true of recovered pottery. Morris concluded that most of it was of Mesa Verdian manufacture or strongly influenced by styles of that area. He observed a similar Mesa Verdian connection in litters of potsherds on the surface of the Aztec mounds. Only actual digging would resolve the questions.

To get excavations under way, Morris assigned one group of shovelers and tenders the task of using hand tools to clear the single row of low cobblestone rooms along the south side of the pueblo. Picks, shovels, and screens were the primary instruments, but occasionally close work required more ingenuity. For example, Morris resorted to the blast pipe off his blacksmith forge to remove fine soil from around delicate objects (see Figure 3.4).

|

| Figure 3.4. Workers removing fine fill dirt by means of a forge bellows. (Courtesy American Museum of Natural History). |

Although the southern contiguous dwellings were discernible and posed no serious difficulties for the crew, they did produce a few surprises for the dig director. The maximum height of walls was less than eight feet ranging down to a one-foot foundation. Other than several stone-lined bins and fire hearths, floor features were absent. Occasional poles and copious amounts of adobe mud were incorporated into partitioning walls. Although a Mesa Verde mug was taken from Room 1, refuse in the fill struck Morris as generally Chacoan. He based this opinion primarily, if not totally, on diagnostic pottery decorated in mineral pigment and a single fragmentary ceramic effigy figure from Room 5. Figurines of this sort were a unique specialization of Chaco potters. Morris had expected the south unit to represent Mesa Verdian tenancy. Moreover, the South Wing structures sat on what appeared to be several feet of dispersed refuse containing Chacoan potsherds. In neglecting to extend excavations down to sterile ground, Morris missed a possible opportunity to determine the extent and kind of earlier utilization of that spot. Although it was not yet recognized as such, some of the recovered pottery (termed by Morris as "archaic") was typically Basketmaker III or Pueblo I in time. This implied an occupation predating the main structure, if not underlying the row of cobblestone rooms at least in the immediate vicinity.

Diggers found three small, circular, subterranean chambers believed to be clan ceremonial rooms, or kivas, in the courtyard just to the north of the cobblestone units. Morris kept no record of the dimensions of these structures and only limited notes about the precise variety of ceramics or other goods retrieved from them. [11]

Kiva A was just inside where the former outer village wall would have been along the southeastern perimeter. Surviving notes reveal that one gallon of pieces of black-on-white pottery and two quarts of grey "coil ware" were recovered during the clearing of this feature. All Anasazi pottery was constructed by a coil method, but Morris used the phrase "coil ware" to denote the ubiquitous grey utility pottery. Coils on the most common cook pots were left unobliterated but crimped to facilitate handling and to better retain heat. Coils on decorated wares were smoothed. Without fuller descriptions, it is impossible to determine regional derivations of these particular earthenwares because all three Anasazi branches made black-on-white and grey wares. Since black-on-red ceramics were not part of the repertories of either Chaco or Mesa Verde potters, a handful of such potsherds likely were remains of trade goods. Apparently in Kiva A, Morris observed no interior architectural features usually present in kivas. This suggests that it might have been a family pithouse in use some time prior to the erection of the final great house rather than being a coeval ceremonial chamber. In 1916, pithouses had not been found or studied in the eastern San Juan Basin.

When discovered, neighboring Kiva B was filled with naturally deposited earth and fallen roof and wall rubble. Its surface depression subsequently had become a dump ground for household sweepings and trash. Excavation exposed an encircling banquette upon which pilasters were raised to support roof timbers. The structure lacked a southern recess, a shank projection characteristic of Mesa Verde kivas, and a sipapu, or symbolic entrance to the nether world. Burials of an infant and a juvenile were among discarded goods littering the floor. Surviving field notes do not specify the kind of associated grave furnishings, if any.

Morris arbitrarily elected to roof Kiva B. For unclear reasons, he used a partially intact, cribbed-log kiva roof at Peabody House (now Square Tower House) in Mesa Verde as a model. [12] He justified the reconstruction to Nelson as being less costly than resetting the kiva's cobblestone walls in cement to withstand exposure. Up until 1984, the replaced flat roof, with its central hatchway at ground level, was noticeable in the southeast court (see Figure 3.5). However, reroofing this relatively minor construction proved to be a mistake. Because of the slope of the terrain and the kiva's situation in the lowest part of the site, underground water percolated into it. The roof prevented natural evaporation, making eventual backfilling of the structure the only possible solution for its preservation. It lies hidden beneath a thick layer of earth along a service road exiting from the southeast corner of the house compound.

|

| Figure 3.5. Roofed Kiva B, 1916. (Courtesy American Museum of Natural History). |

The third kiva exposed in 1916 appeared to have been built within some larger circular masonry unit. It lacked usual kiva elements, except for a firepit and a ventilator tunnel beneath a partial banquette, which did not connect with a shaft to the ground surface. Morris did not determine the cultural affiliation of Kiva C. Modern interpretation suggests it was a pithouse, rather than a kiva, that probably predated the masonry complex to its north side. Kiva C is no longer visible because it has been covered by an extension of the earthen courtyard.

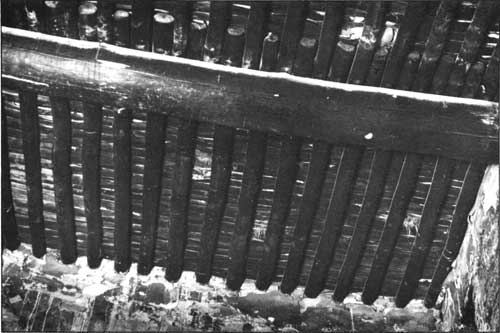

A second group of workers undertook to clear rooms comprising the southern end of the eastern wing of the great house. Cells of various sizes backed up to the solid outer village wall on the east. They were more inset from the court than the uniformly designed complex of rooms to their north and perhaps were tacked on at a later time. The sandstone masonry was composed of a veneer facing over a rubble core typical of Chacoan workmanship. Because of the incorporation of large jagged chunks of purplish concretions, cobblestones, and unsightly daubs of adobe mortar, it was less neatly executed than usual. A stratum of refuse and stubs of dismantled walls lay beneath the surface building. [13] As elsewhere in the ruin, rooms originally had ceilings from nine to 11 feet high. These were made of heavy pine or spruce stringers, small cross supports or peeled poles at right angles above them, and a cedar bark capping (see Figure 3.6). In instances of a second-story room, builders spread a layer of packed earth and clean sand over the bark to create a floor for the upper level. In this part of the village, most ceilings that once had separated two stories were gone. The result was masonry shafts filled with compacted rubble of fallen walls; broken, charred, or sagged ceiling timbers; and some prehistoric trash. Dismantled adobe and cobble walls and Chaco refuse at floor level underlay part of this room block. [14]

|

| Figure 3.6. Exposed first-story roof of primary beams, cross poles, and strips of cedar bark. |

In order to photograph the lower portions of the East Wing rooms, Morris had to sit astraddle the crossbeam of a flimsy, high-legged sawhorse placed over the excavated shafts and point his camera straight down (see Figure 3.7).

|

| Figure 3.7. Morris on an elevated scaffold photographing the ruin. (Courtesy University of Colorado Museum). |

As work proceeded, the East Wing was threatened with being swallowed again in its own residue. Hence, Morris relied on his farm hands to scrape aside this disturbed earthen cocoon through use of teams of horses and fresnos rented from local barnyards (see Figure 3.8). This practice explains an entry unusual in archeological field expenditures for $1.80 to cover the cost of 75 pounds of oats. [15] In order to expose the site more completely, workers laid 2,500 feet of rails through the alfalfa field between the two main mounds of West Ruin and East Ruin. The rails were for operating four steel ore cars drawn by horses (see Figure 3.9). The bulk of the sterile fill from the interior of the western site was deposited along one of the river's banks to the east of Mound H in the southeast occupational zone and away from the surrounding farm. [16] Had work commenced on the western wing of the house block, it was arranged to dump waste dirt in a young orchard to the west of the site that was on ground too low to be irrigated easily. Much of the debris from outer tiers of rooms simply was shoveled outside the village walls (see Figure 3.10). Morris did not adopt an alternate plan of using a sluice box carrying a head of water from a nearby irrigation canal to flush overburden to the Animas River. If he had, many small objects likely would have been lost. "A canal running at the foot of the hill north of the ruins would supply an ample quantity, and the fall is sufficient to enable a sluice box two feet on the bottom to carry all the dirt we could be in a position to dump into it," Morris wrote. [17] Building stone and sound but dislodged roof timbers usable in repair of walls and ceilings were stockpiled.

|

| Figure 3.8. North Wing excavations in 1918. |

|

| Figure 3.9. East Wing excavations in 1916. |

|

| Figure 3.10. Workers in 1916 screening room fill; mine car and tracks to dump in background. |

Anasazi subsistence, which permitted the kind of sedentary cultural elaboration evident at Aztec Ruin, was based on farming. The environment along the Animas valley, assumed to be relatively unchanged over the last 700 years, today is riparian. The soil is fertile loam. However, geographers class the zone as a high desert more than 5,600 feet in elevation with abrupt and often unpredictable climatic fluctuations. The annual precipitation rate is 10 inches or less. Growing season for crops of corn, beans, and squash is 160 days. It is not known that the aborigines had knowledge of fertilization. One thing they did have was a permanent water supply in the perennial river, and they learned how to make use of it.

When Euro-American settlers came into the valley of the Animas in the 1880s, they saw some stretches of prehistoric canals leading off both sides of the river that could be traced for several miles. [18] One crossed what became the Abrams property between the West Ruin and the gravelly terrace to the northwest. [19] Another on the east side of the Animas ran from north of Knickerbocker Arroyo south to Hampton Arroyo, due east of Aztec Ruins. Observers described these ditches as two and one-half feet wide and one and one-half feet deep, with a thick sediment deposit on sides and bottom. [20] Both channels took advantage of a gentle southward gradient. Undoubtedly, they provided water that could be directed onto bordering communal gardens. Modern farmers made use of them prior to digging ditches more suitable for their needs.

Some cultivated land depended on runoff from higher ground rather than on irrigation. Sherman Howe, crew member from a pioneer family, recalled waffle gardens of the Anasazi at the mouth of an unidentified arroyo. At some undetermined time, these plots had been covered by three to four feet of sand, probably deposited by a flash flood. In 1884, a violent summer rain washed away the sediment to reveal the Indian plots. [21] From their small size, modern researchers infer either a restricted production or diversified cropping practices. Probably they were the gardens of villages on the top of terraces, where loam and irrigation waters were lacking.

The canals associated with the Aztec Ruins environs and other sections of ditches near the confluence of the Animas and San Juan rivers were among the earliest to be recognized as part of Anasazi water-control measures. [22] They have disappeared with modern activities.

When Morris's crews finished digging at the end of the summer of 1916, considerable progress had been made in laying bare two arms of the house block and in establishing collection and preservation procedures to be continued in later work. Twelve rooms of the South Wing (Rooms 1-12), 16 of the East Wing (Rooms 13-29, 54), four of the North Wing (Rooms 76, 112, 154, 197), one of the West Wing (Room 121), and three possible kivas had been dug (see Figure 3.11). In correspondence, Morris gave the tally as 34 rooms and three kivas, but this does not jibe with the published accounting. [23] In the plaza clearing, a huge depression hinted at a possible Great Kiva, or community sanctuary, but its exploration awaited the future. Morris packed a sizable collection of specimens and sent it to New York. Its cataloguing was postponed until later. Workmen temporarily repaired some walls. They laid one cement slab to protect an original roof from moisture. They reroofed Kiva B. The combined results of the diverse aspects of the over-all project were sufficiently substantive to assure continuation of the work the next summer. In Wissler's view, the excavation and restoration of the Aztec Ruin would be a noteworthy monument to the American Museum of Natural History. [24]

|

|

Figure 3.11. Excavated units at the time of the establishment of the monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In the summer of 1916, Morris sold the museum a collection of San Juan pottery, which he and his father had acquired over many years of digging. That gave him money to pay tuition and living expenses for a year's graduate study at Columbia University. While in New York, he continued his association with the American Museum.

1917: FIRST FULL-SCALE EXCAVATION

The season of 1917 commenced on June 10 with a labor strike and a change in field procedure. One disgruntled man felt he was not receiving adequate pay. Morris raised wages to $2.50 per day for 25 laborers and added an extra team of horses and a wagon. The tram cars were not satisfactory. The ones on hand had a capacity of only a half yard, but they could not be replaced because of the lightweight rails. [25] Cars and track were sold for $100.

As was his custom, over the winter Abrams grazed his sheep among the ancient mounds. This cropping of the vegetation had some advantage archeologically, as Morris reported to Nelson: "It is now plain to see where Morgan got the addition that he tacked on to the west end of the main building [the Annex]. There are the remains of a very considerable cobblestone structure which appear to run under the sandstone building. I should judge an older ruin." [26]

Intriguing as that idea was, excavation took up where it left off in the East Wing. Ralph Linton, then a graduate student at an Eastern university who worked with Morris on the La Plata drainage in New Mexico and at the Guatemalan site of Quirigua, joined Morris as an assistant. Probably he and Morris shared the house on Abrams's farm, but other than his arrival in June and departure in August, there is no further mention of his contributions to the Aztec project.

The opening days of the season yielded grim evidence of a tragic end for an Anasazi man and four children. The carbonized remains of their bodies were found in clearing Kiva D in the aberrant unit of rooms at the south end of the East Wing. Apparently they had been consumed by a fierce fire, which had raged through the structure, brought down the log roof, and baked the stone walls to a brick red. [27]

Morris put another part of the crew to work opening Kiva E. This was an unusually large chamber isolated and sunk into the courtyard close to the East Wing. [28] Its walls contained lenses of cobblestones set in adobe. Doubtless it would disintegrate rapidly if left exposed. Therefore, Morris ordered a new cribbed-log roof, again based on that in Peabody House at Mesa Verde (see Figure 3.12). [29] Unlike the ground-level roof on Kiva B, this one was elevated above the surface of the court. That was because an aboriginal retaining wall at least seven feet high upon which the roof structure rested encircled the kiva. The reason for the roof style was that Morris believed a Mesa Verde structure was superimposed over an earlier Chaco kiva in the same location. All that remained of the lower kiva was the foundation stones. Recovered artifacts discarded on the floor of the upper kiva were four bone awls, two stone pendants, one obsidian projectile point, and one piece of quartzite.

|

| Figure 3.12. Interior of Kiva E, showing reconstructed cribbed log roof. |

The next phase of the season's work entailed further clearing of the major room block of the East Wing. Work there was slowed by the physical exertions required to mine room shafts from the top of the mound down to lowest room floors and hoist out the debris (see Figure 3.13). Each room was filled with tangled masses of wooden ceiling elements, collapsed walls, drifts of household dust and windblown sand, and some deep strata of consolidated refuse that reached to the mound surface. The workers dumped buckets of spoil dirt into wheelbarrows, outside of walls, or directly into large, flat-bedded farm wagons, which carted the loads to an embankment of an abandoned river channel along the east side of Abrams's farm. Several floor boards of the wagon bed were removable so that contents could pour out. [30]

|

| Figure 3.13. Overview of the West Ruin in 1918 showing roofed Kiva E, Kiva I being cleared with hoist and bucket, storage shed, and capped walls. |

As expected, much of the architecture was that common to the Chaco branch of the Anasazi. [31] The room block was made up of five parallel rows of rooms of equal size spaced from court to outside eastern wall. Access generally was from the court and from room to room. Hallways were nonexistent. The four rooms facing the court appeared to have been added after the remainder of the unit was erected. Their floors were three feet above those of neighboring rooms. Logically, that floor plane was the court level at the final occupation. The exterior eastern facade originally rose sheerly to two stories, with no apertures other than those small ones needed to ventilate inner chambers. Wall cores were rough stone and mud. Aboriginal masons had carefully laid veneers on each exposed surface of tabular sandstone separated by small, neat chinking anchored in limited amounts of mud mortar (see Figure 3.2B). The unavailability in the Animas area of sandstone that fractured into uniform blocks or thin tablets restricted duplication of top quality Chaco masonry. The sandstone used was thought to have been carried from quarries three to four miles away, where outcroppings of Tertiary beds were at the surface. The material was soft and subject to quick deterioration. Walls made of it were battered. That is, they were wider at their bases and became progressively thinner as they rose to the upper story. Although the walls appear not to have been bonded at their junctures, recent studies indicate that they were vertically interlocked as construction progressed.

Door openings were both rectangular and T-shaped and were elevated a foot or so above the packed earthen floors. Series of eight to 12 small, peeled, wooden lintels remained in place. The arid environment forestalled decay. Slanted vertical stone ledges offset at doorway sides were meant to support a stone, mat, or hide closure. At least one corner doorway serving as an interior access angled between a lower and upper room. [32] Openings in this positon are a unique Chacoan construction.

Other features of a few rooms were fire hearths, storage bins, mealing bins, wall recesses, protruding pegs, and ventilator mouths. Some window-like openings between rooms were high up on walls and near corners. [33] There were occasional patches of mud plaster clinging to interior room walls. [34]

As diggers burrowed through the Aztec Ruin mound, it was increasingly obvious that the original building changed over time. Because present-day pueblos are known to be revamped constantly, this was not unexpected. At the West Ruin, some doorways were blocked with masonry. Other openings were altered to make them larger or smaller. Several successive earthen floors were in a single room. For example, in Room 40 approximately five feet of refuse separated the lower floor from a secondary upper floor. [35] An 11-foot ceiling height permitted that kind of reuse.

Detectable reoccupation of at least some parts of the house block presented Morris with opportunity to refine his reconstruction of the site's past history. The notion with which he began the project of joint but segregated tenancy by the two eastern branches of the Anasazi -- the Chacoans and the Mesa Verdians -- or some sort of cultural cross-fertilization of the two was open to question with the new evidence. During the season of 1917, Morris began to speculate about a sequential use of the site, first by Chacoan builders and then by Mesa Verdian migrants. That idea seemed confirmed by finds in Room 38. Fragments of Chaco pottery sprinkled the floor. At some time after the chamber was no longer used, two feet eight inches of fallen masonry obscured the floor. Later the remaining walls above this layer were repaired, and a new floor was smoothed over the debris rather than removing it. Eventually the room again was clogged with four to seven feet of discards including broken Mesa Verde pottery. [36] Applying the Nelson stratigraphic principles, Morris concluded that Chacoans had come and gone before Mesa Verdians moved in. The interval between the two occupations must have been substantial in order for the large volume of trash to have accumulated. With only four rooms thus far studied with demonstrable layered deposits of what appeared to be Chacoan material below Mesa Verde material, Morris admitted the evidence remained inconclusive (see Figure 3.14).

|

| Figure 3.14. Mesa Verde-style wall built on top of Chaco debris in unidentified West Ruin room. (Courtesy American Museum of Natural History). |

At the end of the season of 1917, the crew had opened 30 more rooms of the East Wing (Rooms 31 through 58), three rooms of the North Wing (Rooms 99, 112/122, 113/123), and six kivas (see Figures 3.11 and 3.15). They had repaired the most unstable walls. Less than half of the site had been explored. Wissler had hoped for greater progress, but difficult excavation made for slow going. [37] Four kivas (Kivas D, E, F, and H) had Mesa Verde characteristics, one (Kiva G) was Chacoan, and the style of one (backfilled Kiva I) is unknown. Its four-pilaster plan was unusual. Kiva E exhibited a Mesa Verde chamber placed over a lower Chaco chamber.

|

| Figure 3.15. Excavated rooms and two roofed kivas of the West Ruin at the end of the field season of 1917. (Courtesy American Museum of Natural History). |

The yield of artifacts was great. Although the sort of specialized goods that came from the Hyde Exploring Expedition at Pueblo Bonito was lacking, what was recovered showed how fully and ingeniously the West Ruin dwellers had utilized their environment to create the material paraphernalia necessary to carry on a simple agrarian mode of life.

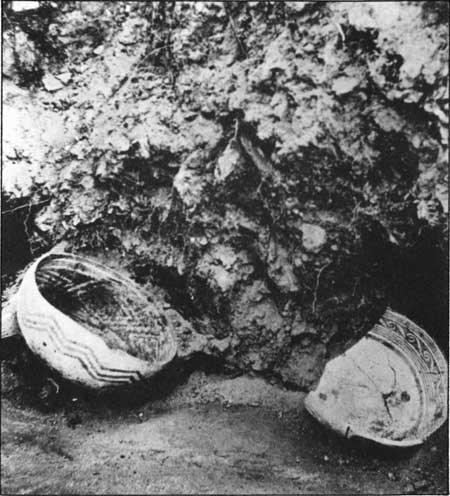

By far the most abundant category of artifacts was pottery (see Figures 3.16-3.19). [38] Presumably, it was made of local clays. At the time of the Aztec project, there had been none of the detailed ceramic studies destined to become central to Southwestern archeology. Even so, Morris had sufficient years of experience with the Animas valley pottery that he felt confident in identifications. He recognized two stylistic schools among the decorated whitewares, or what he called "two-color ware." Combinations of design format and elements, pigment, vessel shape, wall and rim treatments, and degree of excellence in manufacture distinguished Chacoan pottery from Mesa Verdian pottery. By Morris's calculations, a mere five percent of the whiteware ceramic sample was Chacoan or Chacoesque. Its presence precluded other considerations, such as secondary deposition. Although it now would be considered questionable interpretation, Morris counted any level containing Chaco pottery as a Chaco-related level. He regarded the remaining 95 percent of the pottery from Aztec Ruin as being of the Mesa Verde tradition. He used descriptive terms, such as archaic, nascent, or degenerate, to express some of the stylistic variations of the decorated types through time. Morris felt that he could suggest a relative temporal outline of the site's utilization based on pottery recovered and, through extension of the data, could supply a working chronology for the entire San Juan Basin. [39]

|

| Figure 3.16. Room fill contained many shattered ceramic vessels. |

|

| Figure 3.17. Two Mesa Verde Black-on-White bowls in compacted room fill. |

|

| Figure 3.18. Three corrugated jars and a stone-lined mealing bin sunk into a room floor. |

|

| Figure 3.19. Workman sorting potsherds into decorative types. |

Utilitarian pottery was abundant in the debris of the West Ruin. It was a greyware (Morris's "coil ware"), which was both plain-surfaced and corrugated. Large corrugated jars commonly were encountered beneath floors, where they had been sunk to their orifices to serve as storage cists.

Some ceramic trade was represented by smudged and corrugated types (Morris's "three-color ware") typical of a broad area astride the New Mexico-Arizona border to the south of Aztec. Another red-on-orange bichrome identified with the Kayenta branch of the Anasazi was not as frequently recovered at Aztec Ruin.

Many implements were ground or chipped from stone. [40] Among ground objects made from quartzite, granitic pebbles, sandstone, and hematite were generalized pecking, pounding, rubbing, and polishing tools used in construction, food preparation, clothing manufacture, and the making of jewelry. Items having identifiable function in these activities were hammers, mauls, axes, arrow straighteners, tcamahais, sandal lasts, pot covers, pipes, mortars, metates, and manos. The purpose of polished stone slabs, discs, and cylinders was unknown. Blades, knives, drills, and projectile points were chipped from quartzite, jasper, chalcedony, agate, and obsidian.

Stones with pleasing colors or sheen, mammal and bird bones, and shells were the resources from which Aztec Ruin jewelry was fashioned. [41] Selenite, quartzite, quartz crystals, turquoise, and other colored rocks were drilled to be strung into necklaces, anklets, and pendants. The most outstanding example of jewelry of this sort from the season of 1917 was a 57-foot strand of 31,000 black stone beads so tiny that the crew had to rush a flour sifter and a milk strainer into action in order to recover as many as possible from a bed of soft earth. [42] Bone beads, pendants, and foundations for inlays of gilsonite, turquoise, shell, and jasper represented by-products of the hunt. Nine genera of shells, many of Pacific species such as abalone, olivella, Conus, and marine bivalves, were cut and drilled into beads, pendants, or foundations for mosaics. Special ornaments were frog effigies or bracelets. Aboriginal craftsmen strung short lengths of bird bones to make necklaces and anklets. [43]

Other bone artifacts for more utilitarian purposes were awls, fleshers, and spatulas. [44]

One of the most significant contributions to a fuller knowledge of Anasazi material culture was an incredible assortment of perishable goods seldom reclaimed from sites situated in the open. Ten to 15 feet of vegetable substance filled some rooms (see Figure 3.20). [45] The collapse of construction rubble and a very dry environment had served to cap and preserve remains of clothing. In this general category were cotton textile fragments of three different weaves, some bearing red bands; leather scraps, thongs, and bags; feather cloth on a yucca cordage base; sandals of two varieties in sizes ranging from those suitable for children to those for adults; and leather moccasins for an infant. Among woven articles also were rush bags and others formed of cornhusks stuffed into a yucca cordage backing; sturdy coiled and plaited baskets and plaques; headbands or tumplines of woven yucca fiber; braided fiber rings of several sizes; twisted and braided cordage; and pot rests of cedar bark, cornhusks, grass, twigs, or plaited yucca. Wooden artifacts included reed arrows, some with wood foreshafts, feather binding, and plaited bands; digging sticks; prayer sticks with the end occasionally flattened into snake heads; hoops for undetermined uses; painted bark; shaped wooden slabs and cylinders; and flower-like ceremonial objects. Grass ropes; rush and willow matting; reed-stem cigarettes; yucca needles; unfired clay plugs used to stopper ceramic jars; macaw feathers and skeletons from tropical Mexico; deer or antelope hoof rattles hung on yucca cord; corn-cob darts; and yucca or grass-stem hair brushes are the general miscellany left from daily life.

|

| Figure 3.20. A pile of cornhusks found in an unidentified East Wing room. |

Other remains of a perishable nature, which revealed much about aboriginal life on the Animas, were caches in some rooms of raw materials needed for the production of necessary goods. These stores included slabs of cottonwood stacked in a corner, cedar bark for ceiling insulation, bundles of leaves of corn plants, and piles of potter's clay. Diggers also recovered many examples of foodstuffs. They took an estimated 200 bushels of loose corn from Room 41. Brown beans, walnut shells, squash and gourd rind, Mormon tea, and unidentified plants that might have been used for seasonings were other clues to Anasazi diet. Rodents confused the archeological record by bringing modern cherry, apricot, and peach pits into the ruin from neighboring orchards. Those fruits, unknown to the Anasazi, were introduced into the New World by the invading Spaniards of the sixteenth century.

Remains of animals and birds used for food, hides, feathers, and bone were coyote, gray wolf, deer, beaver, mountain goat, antelope, bobcat, hawk, eagle, and other smaller birds. A special find showed that tropical macaws had been traded north from Mexico.

Human burials, in some cases comprising the remains of an unknown number of individuals, were exposed in 1917. Persons of both sexes and all ages were represented. Interments in Room 52 were those of at least 15 children and infants. Some bodies were wrapped in matting and extended on floor or refuse-covered surfaces of rooms, where in time they were drifted over with other trash or detritus resulting from wall or ceiling deterioration. On occasion, bodies were nestled into shallow depressions scooped into unconsolidated household rubbish. Disturbance by rodents or other small animals scattered limb bones, vertebrae, and skulls.

Most burials were accompanied by some funerary goods. Burial 16 from Room 41 produced 119 catalogued specimens. [46] Curators assigned many of these items a lot number because of their small size or similarity, making the actual artifact count considerably larger. Typical articles placed as offerings were pottery, jewelry, and basketry. Burial 16 also was accompanied by a pile of 200 arrowpoints. Since all grave pottery recovered in 1917 was of Mesa Verde affiliation, Morris felt his emerging theory of a two-stage occupation of Aztec Ruin was verified. He suggested that rooms of the great house abandoned by Chacoans were converted into sepulchers by Anasazi moving southward out of the Mesa Verde region to reoccupy the West Ruin.

Even with an insatiable taste for specimens, Morris was satisfied with the artifact returns. Six weeks before field work was suspended in 1917, he wrote Pliny Earle Goddard, curator of ethnology at American Museum of Natural History, "I think you will agree that some of the specimens are among the finest ever brought from the Southwest, and I look forward to the day when the pick of them will have an honor place in the Southwest Hall." [47]

Meanwhile, Morris's desire to dig wherever and whenever possible remained undiminished. After finding a skull and some specimens in a cornfield near the West Ruin, he shot off an appeal to Wissler for authorization to engage in some extra-curricular shoveling. "There are many graves beneath the fields which Mr. Abrams has in cultivation," he wrote, "and one who knows what to look for can locate many of them when the ground is being plowed. Have I your permission to spend a few dollars exploring such burial places as come to light from time to time?" [48] After approval was granted, specimens from 12 sites in the immediate vicinity, but generally not on the monument preserve, were included with the West Ruin collections (see Table 13.1). [49]

The fact that two pieces of pottery in Morris's personal collection at the time of his death came from sites in the environs of Aztec Ruins shows either that additional digging was done or a division of artifacts recovered when he was digging under Wissler's authorization had occurred. [50] In the catalogue to the collection, he described how before sunrise on a Sunday morning he dug a trench in an aboriginal rubbish heap on the Farmer ranch and hit a large, thick-walled corrugated jar and a Mesa Verde mug associated with the skeleton of an adult. The circumstance of most interest to Morris was that the grave pit was roofed, and the vessels had been placed on top of it. This was not a usual burial practice among the Anasazi. [51]

At the end of work in the fall of 1917, Morris felt threatened by the military draft brought on by the outbreak of World War I. Therefore, he spent time cleaning up details and shipping specimens to New York so that operations could be shut down for the duration. On October 25, Morris notified Wissler that, because his mother had sent an appeal to the governor of New Mexico for deferment of her only child and sole support, he had been freed for the present from the obligation to serve in the armed forces. [52] With total expenditures for the season reaching $6926.19, Morris requested another small appropriation in order to fence the site to keep vandals and stock out of the diggings. This request was denied. In December, Morris went East to personally unpack his haul and bask in praise from the museum hierarchy.

1918: THE BIG THRUST

Early in the spring of 1918, in anticipation of resumption of excavations at the West Ruin, J.M. Jackson, secretary of the San Juan Council of Defense, and Hunter S. Moles, San Juan County agricultural agent, lodged a protest with the American Museum over the $2.50 daily wage that was being paid laborers at the site. It was claimed that this wage, higher than what was offered elsewhere locally, lured farm hands away from activities, such as haying, which were essential to the war effort. Jackson suggested that outside help be brought in to do the job at Aztec Ruin. [53] El Palacio, organ of the Museum of New Mexico, reported: "The American Museum of Natural History, in charge of excavation and reconstruction work at Aztec, San Juan county, has given orders that all staff members and employees must assist in farm work in the San Juan valley whenever their assistance is needed." [54] Morris argued that the wages he paid were in line with current practice. With the fruit corp damaged by one of the recurrent early frosts, he regarded the museum payroll to 25 men as vital to the regional economy. [55]

Without consulting Morris, the museum provided him a field assistant for the season. This was B. Talbot Babbitt Hyde. As young men in the late nineteenth century, he and his brother, Frederick, funded Wetherill work in Grand Gulch, Utah, which first recognized the Basketmakers, and a four-year effort at Pueblo Bonito. The collections from both endeavors went to the American Museum of Natural History. In 1918, Talbot retired from business and became an eager volunteer worker at the museum. Since he had no field training in archeology, Wissler suggested to museum president Henry Fairfield Osborn that Hyde be allowed to spend the summer at Aztec Ruin. His travel expenses and maintenance could come out of project funds. [56]

Arriving in late June, Hyde and his wife set up housekeeping in a large, white, walled tent placed in the lee of the unexcavated West Wing. Meanwhile, Morris moved into a newly erected frame shed east of the courtyard Kiva E (see Figure 3.13). This structure was to provide storage and office space as well as temporary living quarters for the field director.

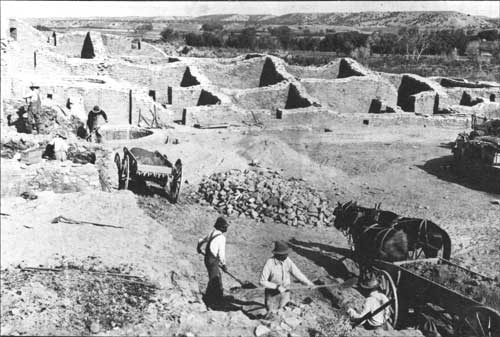

At first, Hyde was enthusiastic about what he observed at Aztec and took it upon himself to dispatch detailed reports to Wissler and Osborn. He recounted how Morris cleverly handled the fracas over using local farm labor in time of war by hiring the protesting sheriff's son and how his pick of a number of applicants permitted assembling a top-notch labor force. Hyde also supplied details that are missing from other records about the ruin, dimensions of its chambers and their condition, and how the compound was being worked. He stated that at the end of July, 2,500 cubic yards of earth and rock fill already had been removed to a dump by three teams of horses and wagons. This laborious aspect of the project could be eliminated, he remarked, if only the museum acquired ownership of the land. The present owner understandably did not want spoil dirt deposited on planted fields adjacent to the house block. As to repair of the prehistoric edifice, Hyde noted that the largest budget item to that point was $500 for a train car of cement to be used in resetting masonry. [57]

The North Wing of the Anasazi pueblo, making up about half the total building mass and up to 29 feet in depth in places, was the arena of the season's attention. At the end of the effort, Morris described the excavation as the most difficult of his experience. [58] The earth's crust was as hard as the masonry stones, and beneath it was a mass of stone, fallen timbers, and dust in which was blended a filthy amalgam of decayed and desiccated snakes, badgers, and rats. Worse of all was the miserable condition of bulging, cracking, and distorted walls. All the unpleasant fill had to be removed in order to reach floor level of the first story. After lifting much of it in two or three stages, some 6,500 cubic yards of material were hauled away. Other unwanted dirt and rocks were shoveled into wheelbarrows to be dumped at the outer walls of the structure. [59]

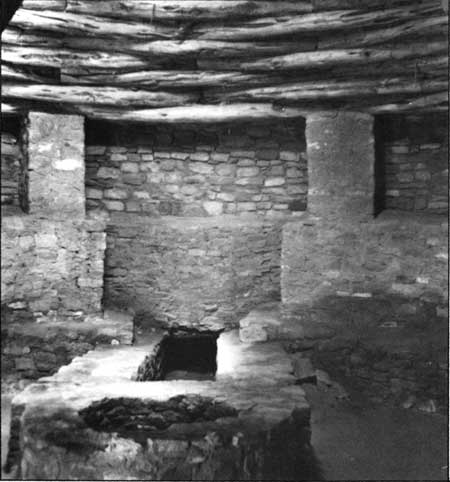

The architecture of the North Wing resembled that of the East Wing. There was the added interest of a series of lower rooms with intact ceilings, those broken into by early settlers, and some plastered walls with painted dados (see Figure 3.21). Rooms were stacked to three stories in places and tiered so that as many as possible could benefit from the solar warmth provided by a southern exposure. Although remodeling suggesting reuse was evident in portions of the North Wing, Morris thought that the northeast corner of the compound had been abandoned and cleared of all furnishings long before Chaco inhabitants vacated the rest of the village. [60] Kivas were of both Chaco and Mesa Verde style.

|

| Figure 3.21. Intact aboriginal ceiling in the West Ruin as seen from the floor. |

Specimens were comparable to those of the previous summer. In a letter of December 6, 1918, Morris wrote Wissler that although the specimen array was less than in 1917, special or fragile articles were more plentiful. [61] Unusual objects were enormous stone hammers weighing as much as 38 1/2 pounds, cotton cloth, coiled and plaited baskets, large mats of plaited rushes, bow fragments, painted wooden altar equipment, and a cradle board with withes and reed stems attached. Associated pottery indicated that burials found on or below floors were those of Mesa Verdians.

With the original appropriation of $5,000 about to be exhausted, in August a supplemental $5,000 was authorized by Robert Lowie, acting curator of anthropology, to carry work into December. Because he felt Morris was sure to be drafted into military service and monies would be curtailed due to the war, it was Wissler's plan to push concerted efforts this season. [62]

The work accomplished in 1918 included clearing 12 rooms in the South Wing, 48 rooms in the North Wing, and four kivas. Rooms 97 and 98 at the exterior of the northeast corner, discovered by Hyde, also were cleaned out (see Figure 3.11). Since "archaic" (Basketmaker III-Pueblo I?) pottery was found in them, they are suspected of having been left from a settlement there before erection of the great house. [63] It was estimated by the end of the season of 1918 that half of the West Ruin was excavated. The first paper of volume 26 of the Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, devoted to the Aztec Ruin project, was in press.

During the summer, friction developed between Morris, the young Western professional, and Hyde, the older Eastern amateur. Morris complained that his assistant was impractical. Hyde's suggestion that some specimens be left in situ as museum exhibits rankled Morris. [64] Wissler agreed that leaving certain floors as an open exhibit would be unwise. [65] Even through Hyde had spent his career in the commercial world, Morris could not bring himself to delegate aspects of the business side of the operations to him. For his part, Hyde carried out supplementary field duties and tried to learn archeological techniques. He did not approve of Morris's methods or what he considered outright procrastination in regard to acquisition of the property for the museum.

Hyde was upset that vandals had broken into the restored kiva and sawed into some of its roof beams. Wooden lintels had been pulled from other rooms. He urged employment of a full-time caretaker, inferring that Morris was unable to control the situation and suggesting that sale of booklets about the ruins and entrance fees for the growing number of visitors could help recoup the expenditure. Morris doubted that funds would be forthcoming for a resident caretaker. Hyde deplored lack of action on fencing the site. This was a need Morris had recognized from the beginning explorations, but he had been unable to persuade the museum to appropriate the money. In 1918, he planned to sell unused cement at the end of the summer to finance the work. If that did not meet the cost, he would draw upon payments made by the county for spoil dirt from the excavations dumped into the rutty road leading to the ruins. [66]

By the end of the year, Morris was ready to settle down to writing reports free of charge and to contemplate the site's development. [67] He wrote Wissler, "My interest in it is the same as if I were doing it upon my own initiative, and with my own funds. Therefore, as far as the future is concerned, you may depend upon me to the limit of my powers." [68] Morris's formal public assessment of the project was that the exploration of the Aztec Ruin eventually would enable researchers to make the most thorough and detailed reconstruction of the material culture of the prehistoric Pueblos than from any other known Southwestern ruin. [69]

To his mentor, Nels Nelson, Morris added a less academic observation: "The court of the ruin is a glare of ice at night, and a veritable pond in the day time. The house we built in it is my present habitation, and I may find it afloat some day." [70]

1919: THE SEASON AZTEC RUIN DATING STUDIES BEGAN

Realization that the Aztec Ruin project might never be resumed at the scale of the earlier two summers came when Morris was notified that the appropriations for 1919 were to be only $4,000. Since this amount was to cover his stipend, maintenance, and automobile expenses, it was obvious that the administration in New York did not foresee much digging. It had been Wissler's plan all along that, after the big thrust of 1918, work at Aztec would proceed at a more leisurely pace with less expenditure of dwindling funds. He just had not told Morris. Beside the practicalities of spreading the project out to conserve money and energy, it would allow more deliberate field analysis and write-up time so that excavation did not overwhelmingly outstrip publication. A one-man scientific staff could scarcely be expected to do all the necessary tasks simultaneously. [71]

In 1919, Morris turned to getting his notes and thoughts in order. At the same time, he continued to act as the museum's representative in negotiations with Abrams and in late summer began construction of a small house at the southwest corner of the aboriginal community.

Meanwhile, some excavation, repair, and cleaning of the site continued. In Room 139 at the juncture of the North and West wings, excavators uncovered a particularly interesting find illustrating a prehistoric medical procedure. A female between 17 and 20 years of age had suffered massive injuries that left her pelvic girdle crushed and her left forearm fractured. Some aboriginal medicine man fastened six splints around the arm, but death came before healing. The crew erected a temporary roof over Room 117 to protect incised mural ornamentation. [72] Outside the structure, the men cleared fallen earth and stone for 100 feet along the east end of the North Wing. They capped exposed sandstone walls with cement.

Two years before excavations began at Aztec Ruin, Wissler became excited about the possibilities of dating Southwestern antiquities through the growth patterns of pine and spruce beams often recovered in them. Actually, he may have been the first American scientist to grasp the potential significance to Southwestern archeology of studies being done by an Arizona astronomer, Andrew E. Douglass, in correlating patterns of rainfall with tree-rings. Following a Douglass article in the Geographical Society Bulletin describing this research, Wissler contacted the author to ask if it might be possible through analysis of their growth rings to date some timbers from Pueblo Bonito obtained through the Hyde brothers. [73] Douglass was interested in the idea but unable to come up with meaningful results.

Undeterred, the next year Wissler wrote the president of the University of Colorado requesting that a young graduate student, who was doing a bit of digging in sites in northern New Mexico under an agreement between the University of Colorado and the American Museum, secure 18-to-24-inch samples from all sound timbers that he might unearth. [74] The student was Earl Morris, who found no wood in the La Plata villages he was working but did submit a log from a Johnson Canyon cliff house to the west and several beams from old houses in the Gobernador area east of Aztec Ruins. These samples likewise proved unusable. [75]

Regardless of these early disappointments, Wissler jumped into action when the Anasazi house at Aztec turned out to be stuffed with ancient door and window lintels, primary roof stringers, and secondary cross members. On April 20, 1918, before work for the summer got under way, Wissler asked Morris to ship Douglass five specimens from the site and five specimens of living pine from the general Animas region. The modern wood could be used for comparative purposes. [76]

Douglass was especially interested to correlate the building of Pueblo Bonito in Chaco with that of Aztec Ruin through dates at which ceiling beams and aperture lintels had been felled and probably put in place. To Wissler he noted, "I think it would be possible to get evidence on the timbers from Chaco Valley and Aztec as to whether the ruins were contemporaneous. If they overlap for fifty years I think there would be a good chance of finding it out." [77] Morris supplied him with six sections from Aztec and three from Pueblo Bonito. Once more, the sample was unsatisfactory. Morris took the samples from unprovenienced stockpiles of reclaimed materials.

Finally in May 1919, nine additional wood samples from Aztec Ruin and Pueblo Bonito yielded promising results. Aztec relative cutting dates extended over two years. One example was cut in autumn, two in late summer, one in early spring, and one in mid spring. The comparative age between Chaco and Aztec specimens remained illusive. Douglass commented, "I am inclined to think that they [the Aztec Ruin Anasazi] had a better average condition of rainfall than has existed for the most part for the last two hundred years." [78] This is a statement at odds with a common explanation of drought having been a factor in the settlement's eventual abandonment.

Taking on the tree-ring dating problem more directly, that fall Douglass made a trip to Aztec to consult with Morris personally about the kinds of specimens needed and how best to obtain them. The fact that he could tap materials still in place in intact rooms was most appealing. After examination of these ancient dwellings, Morris then escorted Douglass to an area about 40 miles north of Aztec in southwestern Colorado known as Basin Mountain. Morris thought this region had been a source for much of the timber used locally by the aborigines.

After having closely examined the in situ timbers and discussing with Morris how best to secure a sample without endangering either the beams themselves or the floors above, Douglass told Wissler that he had made a suitable tool for the task. He added, "I hope with this to get a sample from a large number of beams in the same ruin and check the order of construction as worked out by you. If I can do that and obtain records from trees that were cut at small intervals one after the other I can make out a very much stronger case for myself in the dating of the ruin." [79]

At year's end, Morris had detailed instructions from Douglass on how best to proceed in getting specimens with a small-toothed tubular saw. The tool was designed to cut a core about an inch in diameter from beams still in place that would reveal a pattern of concentric rings from the outer surface, when the timber was cut, to its heart, when its life began. In order to maintain a tight control on provenience data, Douglass suggested that each core extracted be designated by the letter H followed by numbers in order after 30. The hole left in the beam from which the core was removed should be identically identified with permanent markings. Douglass felt it was imperative to take four or five samples from beams in any given room to be sure all were cut at approximately the same time. A comparable series of cores should be secured from various parts of the ruin considered from architectural or archeological evidence to be of different ages. Douglass further wondered if it were possible that the Indians had dragged the logs from the distant hills in the winter using the "snowshoes," willow loops with yucca lacing, which had been retrieved in room fill. [80]

1920: DENDROCHRONOLOGICAL PROMISE AND LIMITED DIGGING

Working during several winter months to bore cores from ceiling beams in the West Ruin, Morris decided the implement supplied by Douglass was not satisfactory because it cut very slowly, was made of too soft material, and was too short. Thinking the cores were too rough, crooked, and incomplete, he quit the task after taking 10 samples from the North Wing. In place of the tubular saw, he suggested a tool modeled after an ordinary bit with the central screw removed. [81]

Within two months, Douglass enthusiastically responded with the startling news that, with only three or four exceptions, every core submitted by Morris showed a reliable relative date in the Aztec series. Even more amazing was that all the dates clustered within an eight-year span. The principal times of cutting were relative dates 524 and 528. [82]

Earlier, Douglass had indicated that a series of relative dates from Pueblo Bonito ranged from R.D. 476 to 487. This meant that part of the great house construction there had occurred some 40 years before the intensive building program took place at the West Ruin of Aztec. [83]

Elated at this progress but astonished at the short interval required to build such a large establishment as the West Ruin without metal tools or mechanical implements, during the rest of the year Morris worked with the tubular saw. Ultimately, he supplied Douglass with 52 tree-ring samples from the West Ruin. [84] The number of specimens available was less than hoped because some logs in the primary structure were found to span two rooms. Timbers from what were presumed to be more recent portions were decayed. Additionally, Morris secured four specimens of living red spruce from Pine Gulch, a rincon some 18 miles northeast of Aztec. He had come to consider that region a more probable source of construction timbers than the more distant Basin Mountain.

In the spring, small-scale excavation continuing in the West Wing uncovered Room 156. It was in the first story along the west wall of the village and was especially well preserved six feet below the mound surface. Much of the original plaster of this room was unblemished. [85] A red wainscoting reached from the dirt floor to a height of approximately three feet five inches. Above that, walls were whitewashed to the ceiling. Nine sets of three red triangles extended from the junction of the wainscoting to upper white walls. The underlying earth-colored plaster was composed of clay tempered with sand. The pale red color seen in this and other protected patches came from solutions made from disintegrated red sandstone applied as washes over the earth-colored coat. White plaster streaked by seepage from above was made from impure gypsum from nearby deposits. Two straight clean pine logs a foot in diameter spanned the ceiling, on top of which was a pole layer of six sets of three cottonwood saplings. A tree-ring sample taken from them in 1934 by Harry T. Getty, of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona, yielded a date of A.D. 1115. [86] White hand prints were daubed on beams in several places. Morris believed the room was of Chaco construction, but masonry-sealed doorways pointed to a later Mesa Verdian reoccupation. A passageway, obscured by modern stabilization, cut through the west wall of the room gave access to the cobblestone structure irregularly sprawled just west of the main house block.

Morris was so pleased with the Anasazi construction skills demonstrated by Room 156 that he hoped to build a full-size replica at the American Museum. He told Wissler that the stones for the masonry could be from elsewhere, but the ceiling members should be original ones taken from the ruin. [87] He probably had in mind the stacks of salvaged timbers saved for future repairs.

On July 23, 1920, the Aztec Independent carried a story about the painted room, which estimated that the village construction had required some 200 pine logs 30 feet long and a foot in diameter, 600 cedar logs 10 feet long and of the same diameter, 1,200 poles of pine and cottonwood, and 100 cords of split cedar splints. The dependency of the West Ruin builders for pine and cedar obviously was upon some undetermined upland source at a distance from the Animas valley.

Workers cleared Rooms 149, 150, and 155 in the extreme southwest corner of the village. These units had relatively high standing walls. The men covered the rooms with modern plank-and-tar paper roofs and converted them into a garage for Morris's car, a blacksmith shop, and a privy. They removed portions of fallen west walls of Rooms 149 and 150 to permit ready access from the modern house then being erected just to the west.

Several walls in these and other West Wing rooms incorporated narrow bands of thin, tabular, green stone set within the typical tan, blockier sandstone (see Figure 3.22). Reasons for these elements are unclear, since when finished, many walls were covered inside and out with mud plaster. That would seem to eliminate aesthetics; however, it may point to a practical use of all available resources but in an attractive way. During Morris's day, the quarry where such stone was obtained was not located.

|

| Figure 3.22. Room in southwest corner of the West Ruin showing bands of green stone inset within more typical sandstone masonry. Modern tar paper roof at center right covered a utility room during the 1920s. Mound at upper left was an aboriginal refuse dump. |

Elsewhere in the site, excavators worked primarily to prevent further deterioration. For example, in a second-story room in the North Wing, they removed a load of debris threatening to break ceiling timbers of the room below from which tree-ring samples had been removed. Laborers hauled 85 wagon loads of earth from this room and from around the ruin to mud holes in the road leading to the site. All these various jobs consumed $800 of the annual budget. Another $100 was spent on ruin repair.

In planning for the future commitment of the American Museum to the Aztec project, Wissler asked for an appraisal from Morris of what was left to be done. Morris replied, "My feeling is that our knowledge of the ruin will not be complete until we have found out the condition and contents of every chamber in it." He went on to estimate that there were approximately 175 unexplored rooms, exclusive of the cobblestone South Wing, which could be exposed and repaired by a crew of four diggers and some laborers working for 700 days at an expenditure of about $3,000. [88]

At the same time, Morris reminded Wissler of an untested depression in the courtyard of the West Ruin, which he judged to be the surface indication of a subterranean Great Kiva. Similar large ceremonial chambers were in Chaco Canyon, several being suspected to grace plazas of Pueblo Bonito. None was excavated. However, in 1920 when the National Geographic Society initiated a new excavation program at Pueblo Bonito, Morris began to agitate for permission to clear Aztec's Great Kiva at once. He longed to be the first to dig such a structure in order to make the Aztec Great Kiva the type example to which other archeologists would have to refer. "I am most desirous of opening and describing this at present unknown type of structure before the Chaco Canyon people dig out a similar one," he wrote. [89] It was not just professional competition and doubtless envy at the ample funding and staffing afforded his colleague, Neil Judd of the U.S. National Museum, but comparable constructions would reinforce Aztec's ties to the grander remains within Chaco Canyon. Morris petitioned to have his crew work on this effort through the winter. To his disappointment, the Great Kiva clearing had to wait until the next appropriation.

1921: YEAR OF SUBSTANTIATED CULTURAL THEORIES AND THE GREAT KIVA

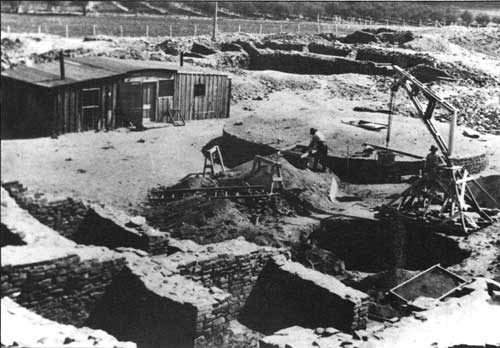

As soon as funds were available in February, work commenced on the Great Kiva (see Figure 3.23). Morris figured that excavation and repair of the structure would take $600 from an annual appropriation of $4,800. [90] Despite cold weather and partially frozen ground, he pushed his crew so that by the end of the month 10 ground-level rooms of a concentric tier of 15 arc-shaped rooms (Rooms 160 through 173) around the upper limit of the kiva were opened and about three-fourths of the subterranean kiva itself was bared. A month later, job completed, Morris already was at work on his report (see Figure 3.24). It was published that same year. [91] A personal race had been won.

|

| Figure 3.23. Excavation of the Great Kiva, 1921. |

|

| Figure 3.24. Excavated Great Kiva in 1921, showing floor features. Above, view to south; below, view to north. |

In addition to the size of the Great Kiva, 48 feet in interior diameter, features that differed from the clan kivas included the 15 encircling surface rooms. All had doorways opening to the courtyard. The largest room on the north axis was enriched with a raised square platform, which Morris called an altar. The rooms were connected to the subterranean chamber by wooden rungs inset vertically into the kiva's masonry wall. A bench wrapped around the lower wall of the kiva. On the floor of the chamber were outlines of two large rectangular vaults that originally might have been covered with planks to make foot drums. Between them was a squared fire hearth. Forming a square at the perimeters of the circular floor space were the stubs of four squared masonry columns, which had supported a log roof over the kiva and its attached rooms. Horizontal layers of small poles were embedded in the columns to reduce their rigidity. During the interval when these features were puzzling the crew because of their unusualness, Morris spent three weeks heading a repair crew at Pueblo Bonito. That gave him the chance to reassure himself that his work at Aztec was correct.

Excavations revealed the beginning, middle, and end of the Aztec Great Kiva. It was sunk into a trashy stratum covering a surface in the south part of the central courtyard, which was peppered with fragments of Chaco Black-on-White pottery. After having functioned for a time as a community sanctuary, the Great Kiva fell into disrepair and collected drifts of trash. Subsequently, the Great Kiva was refurbished and put back into use. Then, final usefulness of the building ended in an outburst of flames that consumed its mighty roof. Morris read this evidence from the ground as an erection of the Great Kiva and its use by Chacoans, a period of abandonment, followed by reuse by Mesa Verdians until a conflagration brought the structure down.

Substantiation for this scenario of phased occupation of the Aztec Ruin came by chance. In the past, Morris and Wissler walked over the southwest corner of the courtyard and decided it was a plot that did not warrant testing. To pass the time in the winter of 1921 while waiting for excavation of the Great Kiva to begin, Morris casually began to shovel there. What he soon discovered were two kivas, one superimposed over the other. The top of the lower unit was eight feet below the courtyard surface. Debris mantling the upper chamber, or Kiva P, contained Mesa Verde pottery fragments. Nearby dwelling rooms produced identical types. The lower and larger kiva, designated Kiva Q, also had been the depository for a large concentration of discarded material goods. Stone scrapers, bone awls, bone tubes, sandstone pot covers, stone skinning knives, worked gilsonite, chipped knife blades, arrowpoints, a flint drill, bone and stone pendants, shell beads, a carved shell disc, turquoise inlay fragments, and yellow pigment came from the fill. What was most electrifying, however, was the relative abundance of the rare Chaco pottery. Morris took 25 complete or partial black-on-white bowls, four black-on-white dippers, one black-on-white vase, one human effigy, one quadruped effigy, and a number of pieces of broken effigies of Chaco-style ceramics from this structure. [92] Because there were no Mesa Verde ceramics mixed in with this deposit and Kiva Q was situated beneath Kiva P, Morris was certain that he had the most indisputable evidence thus far encountered for his hypothesized sequence of occupation. It had been four years in coming.

Wissler responded to this bit of news, as he replied, "I am quite pleased with your recent pottery find where two time periods in the history of the ruin seem to be differentiated. I hope you will make the most of this discovery." [93] Of that, there was no doubt.

While enjoying the satisfaction of this accidental discovery, Morris made a second surprising find diagonally across the courtyard at the juncture of the East and North wings. Work in 1917 in this area had not gone beneath the hard-packed surface. In the spring of 1921, Morris stumbled onto another refuse-filled kiva [Kiva R?] under four feet of detritus there. It was crammed with potsherds representing what he considered the richest ceramic complex he had ever seen. Chaco types predominated, but in addition, there were variants new to Aztec and some trade pottery. To Morris, an earthenware effigy of a human male with well developed genitals and lines representing sandal ties on one foot clinched the Chaco affiliation of the deposit. [94]

In retrospect, it now appears that the room Morris found may have been a pithouse rather than a ceremonial room. He described it as a pit dug into the earth and plastered, with no bench or pillars. Perhaps after its abandonment, it had become a dumping place for later trash. The finding of this buried construction and that deeper one at the opposite corner of the pueblo showed Morris that from the beginning of explorations at Aztec Ruin he should have looked for superimposition in the courtyard. [95] To rectify this oversight, he immediately dug test pits in other parts of the courtyard fill. He found that at least three feet of deposition had accumulated in some sectors. However, at the time he did not happen upon any further constructions. Diagnostic potsherds scattered at lowest depths further convinced the young archeologist that Chacoans had been there first and for a considerable interval. [96]

Although Morris sought an additional $100 to stabilize the earthen walls, the second structure bolstering his reconstruction of prehistory of Aztec Ruin is obscured beneath the court. [97]

Wissler rationalized over the events of the spring as he mused to Morris, "It seems rather curious that we should have begun at just the wrong end of this ruin, but perhaps it is best as it is because we shall have worked over the whole in anticipation of the solution." [98]

The good fortune of the season of 1921 continued with the finding of Burial 83 in Room 178, the sixth room south from the northwest corner of the compound. [99] An adult male more than six feet tall, an unusual height among the short-statured Anasazi, was laid out in a shallow pit in the floor. The body was wrapped in feather cloth and rush matting. A tightly-woven, coiled basketry plaque three feet in diameter, with colored fibers and a decorative border of flecks of selenite, covered the remains. Morris called it a shield. A similar piece of basketry was taken from one of the Mesa Verde cliff dwellings by early explorers. That underscored the probable cultural affiliation of the Aztec deceased. Although they generally would be regarded now as utilitarian digging or game sticks, three wooden shafts suggested swords to Morris. He saw stone tools with wooden handles as weapons. A number of examples of pottery, basketry, jewelry, and stone implements were placed as offerings about the body. Obviously, the man in Burial 83 was someone important in the village. When Morris colorfully described him as a giant warrior, he made good newspaper copy for reporters, who in the early 1920s had a propensity for sensationalism when discussing the unfamiliar civilizations of the Wild West.