|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 13: SPECIMEN COLLECTIONS: RECENT ASSESSMENTS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY COLLECTION

At the conclusion of each excavation season from 1916 through 1919, artifacts recovered from the West Ruin were packed, taken by freight wagon to the nearest railhead, and shipped by train to New York. As the excavation drew to a close in the early 1920s, most items, other than human remains, were kept at the site, either because they duplicated those already at the museum or because their weight or shape made shipment impractical. A total of 5,220 specimens eventually were deposited in the American Museum of Natural History. [1] Because he was concerned about rough treatment from those who did not share his personal involvement, for the first three seasons Earl Morris went East to take charge of unpacking the boxes.

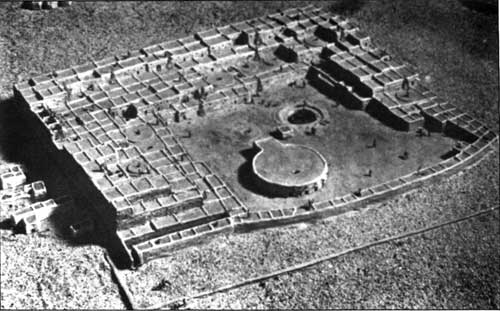

Some exhibits of Aztec Ruin finds were arranged. Early in the program, these were for staff only. During the 1920s, permanent exhibitions were installed in the museum's Southwest Hall. So far as is known, all that was included were two cases of pottery and a large model of the ruin (see Figure 13.1). How long these displays were mounted is unknown. [2]

|

|

Figure 13.1. Model of the West Ruin prepared for exhibition at the American Museum of Natural History. |

In the 1950s, the Southwest Hall at the museum was closed. All the Aztec Ruin materials then were relegated to an archeological heaven filled with rows of identical metal storage cabinets holding the rich hauls of Anasazi material goods from Grand Gulch (1893-94, 1899), Chaco Canyon (1896-99), and Canyon del Muerto (1923-28). These were finds which were instrumental in igniting the fires of scientific and lay interest in the prehistory of the Colorado Plateau. Twenty-three similar cabinets were needed for the Aztec Ruin collection. One tray in these cabinets was filled with the results of Nels Nelson's test trench in the southeast refuse mound at the Aztec Ruin. A 24th cabinet contained a pottery collection from the lower La Plata valley of New Mexico, which it is assumed was that sold by Morris to the American Museum to finance his graduate studies at Columbia University during the academic year of 1916-17.

In Morris's opinion, the Aztec Ruin collection at the American Museum represented the best artifacts retrieved in terms of workmanship, physical condition, uniqueness, or characteristic features. He wrote Wissler, "I culled the cream in the way of especially fine and unusual objects, and sent them on to you." [3] Morris made the selection to give the donor who underwrote the project tangible returns for his investment and to cement his own reputation with the museum as a producer. He emphasized intact objects or those sufficiently complete to be identifiable and therefore suitable for display. The scraps of household sweepings and everyday discards such as form the bulk of most archeological field collections were noticeably absent. When saved, those were among specimens left at Aztec.

There is some basis for being critical of this attitude because an on-site museum always was in the background of long-range plans. Perhaps Morris and Wissler regarded the Abrams allotment as sufficiently diversified to adequately stock such a facility. Morris's own appraisal of what was left at the ruin was expressed candidly in response to an inquiry from Wissler. "The bulk of the stuff [remaining at Aztec Ruin], aside, of course, from some good pottery, would be of great value for study, but most unprepossessing for exhibition." [4]

The collection in New York is eminently suitable for both display and study. Morris published one paper describing artifacts obtained during the first two seasons in what was one of the earliest descriptive reports of Anasazi material culture from the San Juan Basin. [5] The collection was greatly augmented thereafter and has never been analyzed. Although Morris intended to prepare a detailed monograph covering the total assortment, the pressures of other work, the loss of some notes, and family illness prevented him from doing so. Despite the passage of time, a straightforward account of these items still would be of interest in order to fill gaps in the inventories of Anasazi worldly goods. But perhaps of more value would be expanded studies in the light of recent research, using the Aztec data as a base.

For example, Morris based his theory of sequential occupations of the West Ruin on a number of stratified deposits wherein, according to his interpretation, Chacoan refuse was beneath, and therefore older than, Mesa Verdian refuse. Other than pottery, he failed to identify or describe specific cultural items that might distinguish the two. His separation of the complexes of artifacts was not done on mere intuition but on field experience and familiarity with the results of other research. Much of that research remained unpublished and unavailable to those outside the inner circle of field workers.

It has been the sad history of San Juan archeology that publication has lagged many years behind field work. The Hyde Expedition work at Pueblo Bonito during the 1890s was published in 1920, and National Geographic Society excavation studies at the same site in the 1920s did not appear in print until 1954, just two years before Morris died. An artifact collection with some relevance to Aztec Ruin recovered in 1947 at Chetro Ketl in Chaco Canyon finally was described in a publication in 1978. At Mesa Verde, modern research began to catch up with past "relic" collecting during the 1950s and 1960s, when the National Park Service and the University of Colorado unearthed and published on findings of the local aboriginal material culture. The large, culturally related Salmon Ruins west of Bloomfield, New Mexico, was excavated but only partially reported on in the following decade. A comprehensive interpretive report is yet to come.

However, now a century after discovery and earliest exploration, it might be possible to detail contrasting diagnostic elements of each major contributor to the Aztec Ruin story -- Chaco and Mesa Verde. Through such sorting out of material possessions, insight into degree, kind, and length of occupancy of the house block might result. The cultural biases peculiar to each occupation might be defined. The results of the 10-year study in the 1970s of Chaco Canyon archeology reveal the complex of Aztec Ruins as the most important outlying aggregate settlement at a distance from the canyon proper but contributing in undetermined socio-economic ways to the well-being of the core communities. This revelation underscores the need to understand exactly what constituted Chacoan material culture at Aztec Ruins and whether it represented a colonial transfer of actual goods or an imitative process by persons already living away from the principal Chaco center.

Dominating the American Museum assortment are pottery vessels. The more than 186 burials found within the protective walls of the house block, rather than in trash mounds strewn in the open, account for an unusually large number of unbroken earthenwares that had been placed beside bodies as funerary offerings. Grave 25 in North Wing Room 111, for instance, contained more than 50 pieces of pottery. Over subsequent centuries, other grave vessels were crushed in situ by falling beams, masonry, and trash. Excavators were able to gather up their fragments for reassembly. After work shut down for the day, Morris spent hours by the light of a kerosene lamp fascinated by the jigsaw-puzzle process of putting pots back together. According to Talbot Hyde, his field assistant one year, this was done at the expense of keeping notes or cataloging specimens. [6] Other reconstruction was completed while Morris periodically was at the museum in New York between field seasons. A fair number of pots could be only partially reclaimed. The few sherds left in the storage trays likely were pieces that did not fit. The Morris field catalogue indicates 398 pieces of ceramics at the American Museum. This contrasts to 264 vessels recovered during American Museum excavations now divided between Aztec Ruins National Monument and the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. Many of the pots still in the West were restored by the Civil Works Administration project of 1934. [7]

The pottery collection from Aztec Ruin never was described as such, but background information obtained from it surely was incorporated into the rather exhaustive treatment of regional ceramics included in Morris's later large monograph on sites in the neighboring La Plata drainage. [8]

Approximately 160 vessels in the collection at the American Museum can be definitely assigned stylistically to the modern McElmo Black-on-White and Mesa Verde Black-on-White classifications. They were the principal evidence for what Morris interpreted as a reoccupation of the West Ruin by persons affiliated with a Mesa Verdian cultural orientation. Of the Mesa Verde pots, there are 132 bowls in a range of sizes from small to very large. Other forms represented are mugs, ladles, kiva jars, canteens, forms with modeled animal representations, and necked jars.

At least 25 vessels are of the Chaco mineral-paint tradition, but some of these may more properly be considered Mancos Black-on-White. That is a Pueblo II style that was a precursor to the vegetal-paint Mesa Verde series but with wide distribution both north and south of the San Juan. Almost exclusively, the Chaco types were recovered from refuse. They include bowls, pitchers, seed jars, and necked jars. One bowl retains a leather thong passed through holes on either side of cracks to cinch the vessel together. This method of vessel repair is commonly seen but rarely with the vital connector in place.

Although at Aztec Ruin, as in other Pueblo II-III communities, corrugated cooking and storage vessels were much more frequent than decorated service ones, they are not numerous in this collection. That is because of the selective standards by which the assortment was amassed. Many corrugated earthenwares were recovered at Aztec, buried beneath floors of the house block, where they had been used as storage cists (see Figure 3.18). Others were retrieved from drifts of trash. These and still others remained at Aztec. They were mostly in broken condition until the Civil Works Administration project. Several unusual corrugated examples, which did get to New York, were a tiny three-inch-high jar found with its stone lid beside Grave 29 in Room 141 and a partial jar whose corrugations were overlaid with applied clay spines. A similar spiked, small-mouthed, lugged olla lacking corrugations is on exhibit at the monument. It was taken in 1925 from Room 193 in the North Wing, when the season's work was done under permit from the National Park Service. A black-on-white sherd with spines is illustrated by Morris in his first detailed Aztec Ruin report. [9] It came from a small house 150 yards north of the northeast corner of the Aztec Ruin. Was this uncommon spiny form of decoration a local idiosyncrasy?

Unfired clay plugs, some with fingerprints, used to stopper utilitarian earthenware jars and a series of flat, shaped, stone jar covers round out the inventory of basic cooking and storage receptacles.

Neither the Mesa Verde nor Chaco examples of the usual earthenware forms are of the top quality of these two traditions as seen in the centers of their development. Why this should be so is a matter to be resolved by future research. Are the reasons temporal, provincial, or because of a local imitative manufacture? Or a combination of all three? If physical analyses were done, perhaps trade exchanges could be identified through ascertaining types of temper used.

Among the Chaco exotic ceramics are crudely modeled effigy vessels generally bearing some black decoration over a white ground. Most of the 25 examples in this collection are fragments of deer, skunk, birds, frogs, unidentified animals, and humans. The projections of their appendages made them subject to breakage. [10] Eight fragments were from Room 47 in the East Wing. This chamber was filled up to eight feet with what Morris classed as Chaco rubbish. Another four pieces came from Room 48 next door, a room also crammed with Chaco waste. [11] Kiva Q beneath the southwest corner of the West Ruin courtyard yielded at least a dozen pieces of Chaco pottery. Among them were a nearly complete seated deer or mountain sheep figure (F.S. 4304) and a partial squatting hunchback figure (F.S. 4303) with arms on knees but lacking left leg and hand. Both objects have been heavily restored. Probably the work was done by Alma Adams, who repaired many of Morris's personal vessels and later was employed to work on specimens at Aztec. In most particulars, the human figure was like a more fragmentary specimen taken from the fill of Room 47. [12] On both humans, black lines indicate facial features, hair, body tattooing, and arm or neck bands. Faces are flat, ears are pierced with holes (maybe for suspended earbobs?), and basal air holes prevented breakage during firing. A comparable but finer example was owned by Mrs. Oren F. Randall, of Aztec, who once loaned it to Custodian Boundey for exhibit. [13] They also are reminiscent of fragments illustrated from Pueblo Bonito and presumably like a specimen taken by John Wetherill from a grave near Pueblo Alto in Chaco Canyon. [14]

The human effigy at the American Museum is particularly intriguing because in the same storage case is a near-twin. The second effigy was purchased in the early 1920s by Morris on behalf of Charles Bernheimer from a collector in Blanding, Utah. The lower legs are missing from this figure. Blanding was, and has remained, a hotbed of pothunting activities. The provenience of this specimen probably was not nearby, since no Chaco outlier community is known thereabouts. It could have been a trade item or trophy, which got far beyond its usual range. At any rate, Bernheimer was another of the museum's wealthy patrons of the time, who eventually must have donated this figure to that institution.

The possibility of the use of molds to form effigy figures such as these would be a worthwhile study contributing to the knowledge of Anasazi ceramic technology. The distribution of the finished products would add to information about Anasazi interactions. Did the figures have esoteric meaning or, less plausible, were they merely fun? Or, as among Pueblos today, were they made for commercial reasons? The hunchback figurines might be part of the cult revolving around Kokopelli, the ubiquitous Anasazi fertility symbol.

A rather impressive trade pattern is inherent in an estimated 33 vessels originating in other parts of the Anasazi world but exhumed within the West Ruin. These include a variety of redwares that were characteristic of the Kayenta district, Kayenta-allied colonies in the so-called San Juan Triangle, or the Little Colorado drainage. These are areas as much as several hundred miles west and southwest of Aztec in northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah. Another group of imported ceramics were black-on-whites and highly burnished brownwares with manipulated exterior surfaces from the region south of Zuni straddling the New Mexico-Arizona border, also more than 100 miles away. Most of the recovered trade pottery came from portions of the West Ruin Morris regarded as Chacoan. That fact takes on added significance when considering the network of roads, probably at least in part an aspect of trade, now known to have laced together the Chaco domain and the prevailing absence of foreign pottery in sites on the Mesa Verde proper. A study of the long-distance traffic in very breakable ceramics in the eastern San Juan Basin might revolve around the Aztec findings, which represent some of the most northerly and easterly occurrences of these alien types.

The American Museum excavators found 10 trade vessels in Room 111 in the North Wing. Since they were part of a rich burial, they might have represented a valuable offering or perhaps the personal property of a trader. [15] The workers also recovered similar pottery in adjacent Kiva L. Morris calls this the largest concentration of Tularosa ceramics encountered in the ruin. [16]

During the thirteenth century, dozens of small cobblestone houses peppered the environs of the Aztec Ruin. Because quantities of carbon-painted Mesa Verde ceramics were found in them, Morris attributed them to an occupation by a population allied to the Mesa Verdian cultural orientation. In 1915, a plowman turned up 86 complete vessels of this type at one site 50 yards north of the east end of the Aztec Ruin. The man's plow shattered an unknown number of others before he was stopped. [17] Because he gave most of the recovered vessels to a scientific institution, Morris rationalized his own pothunting in these sites as justifiable. That accounts for pots from 12 sites outside the West Ruin being included with the American Museum collection (see Table 13.1).

|

Table 13.1. Animas Valley Sites, other than West Ruin, Yielding Pottery in the American Museum of Natural History Collection.a

a Earl H. Morris, Field Catalogue (Aztec Ruins files, Department of Anthropology Archives at the American Museum of Natural History, New York; Collection Accession files, Aztec Ruins National Monument Headquarters, Aztec, New Mexico). |

Specimens from a dwelling 225 yards east of the West Ruin include objects representative of the entire Anasazi continuum from Basketmaker III through the Pueblo II and Pueblo III periods of both Chaco and Mesa Verde branches. That is an estimated span of some 600 years. A Basketmaker III vessel from another house 125 yards west of the Abrams farm is a further clue to an early occupation of the valley. Diggers unearthed a child's burial in Room 106 in the South Wing of the West Ruin, which was accompanied by a Basketmaker III-Pueblo I bowl. One may guess that it had been obtained from vandalizing some earlier remains in the vicinity. The question of horizons both predating and postdating the West Ruin complex may be dealt with in part through these and similar pottery finds.

The basketry in the American Museum collection from Aztec Ruin, of which there are at least 74 examples of various types and completeness, has never been studied. A twilled ring basket with concentric-diamond pattern and several relatively insignificant coiled fragments, a plaited rush bag, and a meshwork basket-like container were mentioned by Morris after the season of 1917, but he delayed further discussion of this category of objects in anticipation of better specimens to be uncovered in later work. [18] He included basketry in the gross enumerations of specimens recovered in each of the rooms. [19] Morris's definitive study of Anasazi basketry done in collaboration with Robert Burgh 24 years later did not include Aztec Ruin specimens. He stated that, although 24 coiled baskets had been recovered there, he did not have time to do the necessary cleaning and meticulous retracing of patterns to include these materials in that publication. [20] The only other recognition the Aztec Ruin basketry has had are a published photograph of one large plaited basket associated with a set of antlers from Room 95 in the North Wing and a badly worn coiled basket, which was recovered in Room 178 in the West Wing with the so-called Warrior's Grave and its large basketry shield. [21]

Included in the American Museum basketry assortment from Aztec Ruin are 25 close-coiled baskets or remnants. This count is one more than Morris's statement above. Some are so tight, firm, and bright that they seem to deny their 700- or-800-year age. Present also are five sausage-shaped plaited bags, six rim frames laced with yucca strips, one cylindrical reed basket, two plaited plaques, three coiled plaques, 12 plaited yucca baskets or their fragments, two baskets covered with a hardened red clay, and three meshwork containers still stuffed with tinder-dry corn husks. A very unusual item is a basketry ladle or dipper coated with red clay, which has a pebble rattle enclosed in the handle. This came from Room 189, cleaned out late in Morris's tenure at Aztec Ruin. The ladle was sent to the American Museum because of its uniqueness.

Although Morris wrote that all specimens were from the Mesa Verdian reoccupation, it seems probable that examples of Chacoan basketry arts are present in the American Museum collection. [22] He contradicted this in another passage by assigning the objects covered with red clay to Chaco refuse. Five additional specimens came from Room 48. Included with the Chaco trash was a cylindrical reed basket. Neil M. Judd found both basketry covered with red clay and cylindrical baskets at Pueblo Bonito. [23] Since Pueblo III Chaco basketry carried designs distinctive from those of Mesa Verde, it should be possible with careful analysis to more precisely determine cultural affiliation of the Aztec Ruin basketry.

Eighty-five sandals exhibiting various degrees of wear in sizes suitable for children and youths to those for adults are in the American Museum collection. Another 19 are at Aztec Ruins National Monument and the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, most having been recovered during American Museum work. The large number of these objects is due to the dry environment within the rooms. By contrast, Judd recovered just 15 fragmentary sandals during his work at Pueblo Bonito. [24] Morris borrowed some of the Aztec sandals for a proposed study of the entire Anasazi sandal craft from Basketmaker II through Pueblo III. It was a project never completed. Analysis of the Aztec sandals would fill out data concerning late Anasazi costume and weaving skills.

Two kinds of footgear are in this assortment. The coarser were twilled of pliable strips of undecorated yucca in an over-two-under-two weave. The finer type was of twined yucca or dogbane fiber cordage tightly woven to create an exceedingly thin, hard foot cover. Although these sandals appear fragile, they must have been fairly durable. Many of the Aztec specimens have black, brown, red, or yellow designs on the under surface. These resulted from use of dyed weft threads. The surface next to the wearer's foot was enriched by supplementary warps and wefts variously wrapped around each other.

A third kind of possible footgear, which thus far is unique to Aztec Ruin, are what Morris speculated were two pairs of snowshoe pads. These were willow loops crossed by yucca-strip lacing and padded with either corn husks or grass bundles. [25] Whether or not they were intended to get a wearer across a snow field is debatable.

Another aspect of the weaving skills of the residents of the West Ruin to be studied is the collection's 67 cotton textile fragments and 13 examples of cotton cordage. Generally white, some textiles also carry red or brown patterns. The quality of the cloth varies from fine to coarse and appears to have been constructed by several weaving techniques. The cotton itself would not have been grown in the vicinity.

Two assortments of wooden objects are in the New York collection. These should be examined forthwith. After recovery in 1918, the artifacts were stored away virtually unnoticed. Research since then has greatly enhanced their interpretive value. In 1947, a large find of comparable articles was made at Chaco's second great house, Chetro Ketl. It was not published until 1978. [26] Some similar, but not identical nor as numerous, objects were removed from Pueblo Bonito in the 1920s by the National Geographic Society but also were not described in print until 30 years later. [27] But it is the Chetro Ketl material that makes it most obvious that the Aztec examples were physical accoutrements of rituals practiced in Chaco at least by the late eleventh century and perhaps diffused some time in the twelfth century to the settlement on the Animas. Analysis of the Aztec sample would be an important contribution to interpretation of Anasazi ceremonialism as expressed by the Chacoans. Can these articles be attributed to a particular cult or group, perhaps with modern Pueblo counterparts?

The most exciting of the wooden objects are what may have been altar paraphernalia, headdresses, or items carried processionally. The American Museum crews retrieved 14 specimens in Room 72 of the North Wing. This is a unit in the first tier of rooms north of a large kiva within the house block that had been Chacoan originally but was remodeled by Mesa Verdians. Morris reports that when a wall of an adjacent chamber collapsed, it opened up the ceiling of Room 72. That allowed some five cubic yards of cultural materials and vegetal debris to pour down from the second story. The wooden specimens were part of a spill of what Morris considered Chacoan rubbish. Later refuse was dumped over this stratum. Pack rats disturbed the stratigraphy by dragging some of the wood upward through the secondary fill. [28] Considering the relatively crude excavation techniques of the times, it is more than likely that small pieces of the wood, especially those without applied color, were shoveled out with the fill. Excavators found several other specimens of the same style in two north rooms showing little or no domestic use. Perhaps the dark, inner chambers next to the village wall were storage chambers, and Room 72 overlooking Kiva L's hatchway was the dwelling of a clansman charged with caring for the ritual gear.

What were reclaimed are small, thin, flat pieces of wood that had been worked into various forms and had been painted. [29] Included are disc-shaped pieces with serrated green edges, flattened crescents, perforated rectangular slabs with blue, green, and white patterning, and curvates. Four green pieces reminiscent of leaves of a fan are attached to a central stave. Another fan form is green and red. Both fan-like specimens may have been representations of bird tails or perhaps nonfunctional arrows. A more obvious bird tail is made up of two wood pieces striped with green and blue pigment and tied together with yucca cord. An unpainted human arm of thin wood is attached to a green hand. Part of a human body is green. A wooden sandal last is blue, red, and green on both surfaces. [30] One smoothed wooden cylinder has black and red decoration.

A second grouping of related wooden objects consists of an estimated 45 ceremonial sticks such as also have been reported from Pueblo Bonito. George Pepper found 375 of these items in one room; Judd's excavations uncovered 16. [31] The Chetro Ketl collection likewise includes a few examples. [32] These are long slender rods worked in various ways at one end and tapered at the other. Seven of the Aztec specimens are bow shaped rather than straight. Some rods have knobs on one end. Bits of cloth adhere to a few. Incised spiral lines decorate others. Excavators found the ceremonial sticks in Rooms 111 and 112 in the North Wing adjacent to or two rooms removed from Kiva L, a large Chaco-style construction.

In addition to the ceremonial staffs, another kind commonly known as prayer sticks, or pahos, have straight shafts topped by a carved serpent head. These have been found throughout the Anasazi territory.

Although unimposing because of their mundane nature, the wealth of inflammable and perishable materials from Aztec Ruin now in storage at the American Museum offers a marvelous opportunity to gain some understanding of how the Anasazi ingeniously coped with a rigorous close-to-the-earth mode of life. Articles made from bark, sticks, mammal hides, sinew, rabbit fur, turkey feathers, grass, cotton, and two principal plants -- domesticated corn and wild yucca -- reveal how they were able to implement their lives. From such raw resources, the inhabitants of the West Ruin created weapons, clothing, blankets, toiletries, cordage, ties, cigarettes, fire hearths, pot rests, cradle boards, arm splints, sandal lasts, matting, farm tools, objects with religious significance, and many things whose meaning is lost. A variety of dried plants and animal remains testify to what was being stockpiled for consumption and discarded as garbage. No Chaco great house has yielded such a bewildering array of this kind of raw data; the perishables which banked the rubble of the Mesa Verde cliff houses were dissipated a century ago by looters and collectors.

Morris got off to an exhilarating start at Aztec Ruin with finding several burials in Room 41 of the East Wing of individuals who had been adorned with quantities of primitive jewelry. These were necklaces, bracelets, pendants, anklets, and mosaic inlays of stone, bone, and shell. Morris made another discovery of interest in this regard the following season of a grave in a North Wing room containing someone of unquestioned importance. He had been outfitted with a 12-foot strand of 865 white bird bone tubes alternating with 444 black beads, a strand 13 feet long of white stone beads, and assorted turquoise, abalone, lignite, and olivella shell ornaments. These goods of adornment enlivened Morris's reports of almost seven decades ago. [33] They now would benefit from modern photography, reanalysis, and comparisons with subsequent jewelry finds, such as those made in Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Salmon Ruins.

The remainder of the American Museum of Natural History collection consists of a sample of bone awls and scrapers, stone projectile points, tcahamias; grinding, polishing, and pecking stones; manos, metates, pot covers, mauls, axes, and mortars. [34] One set of artifacts consists of a few adobe bricks, which Morris took from a late eleventh-century site on the property of Oren Randall near Estes Arroyo. [35]

Although Morris states that he sent all human remains recovered at Aztec Ruin to New York, the catalogued entries there total just 71, two of which came from locations away from the monument. Morris recorded 186 burials. [36] It must be assumed that some specimens were too fragile or fragmentary to be retained. Physical parts of 35 children or adolescents point to a high rate of infant mortality comparable to that noted elsewhere among the Anasazi population. In addition to 13 fairly complete skeletons of persons of all ages, a few still wrapped in feather cloth and rush matting, the Aztec Ruin physical anthropological specimens in New York include crania, jaw bones, hair, foot bones, miscellaneous long bones from a number of individuals, and one example of charred brain matter. At the American Museum, the human remains were withdrawn from the general archeological collection to be put with physical anthropological materials. Associated objects, such as jewelry, cloth, matting, or in one case, wooden splints around a broken arm, were kept with the primary specimen lot. The human remains have never been studied or exhibited.

Finally, a few small clues to Anasazi awareness of the world beyond their territory are in the Aztec Ruin collection at the American Museum. Feather, three skulls, and a skeleton of macaws, two tiny globular copper bells, and three beads of rolled sheet copper somehow worked their way northward from central or northern Mexico at a time from two to three centuries before the rise of the Aztec Indians for whom this distant settlement erroneously was named. The assumption is that these trade goods reached Aztec Ruin during its Chacoan era as a result of the flourishing trade network now known to have connected north central Mexico to the Colorado Plateau. This point needs to be verified, old data permitting, because of the absence generally of such commercial contacts between Mexico and the more geographically and culturally isolated Mesa Verde branch of the Anasazi.

Aside from consideration of the physical attributes of the various kinds of objects, it would be informative to plot out their proveniences within the house block to ascertain whether meaningful use patterns can be established for the structure. For instance, do the 110 stone tools and assorted beads and bits of colored stone and turquoise found in the fill of Room 110 in the South Wing imply some sort of workshop? Can various stockpiles of raw resources, such as potter's clay, cedar bark, bundles of corn husks, or hanks of cordage, be related to chambers that might have been a part of the collection and distribution system of the Chaco Phenomenon? Can religious articles be tentatively assigned to particular kivas or surrounding rooms of clan members? Once they have been adequately defined, can Chacoan and Mesa Verdian refuse be used to map tenancy patterns through time?

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COLLECTIONS

There are two collections of specimens from Aztec Ruins National Monument in the custody of the National Park Service, one at the monument and one in the depository at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center in Tucson. Two main accessions of these articles do not belong to the government, however, but remain the property of the American Museum of Natural History. Not only has there never been a gift of any artifacts to the National Park Service, but the American Museum never has extended to the National Park Service any permanent loan agreement. Recent correspondence indicates that so long as curation remains reasonably adequate, the museum will be satisfied to have the collection stay where it is and a formal loan document may be prepared at some future date. [37] After almost 70 years, there is no feeling of urgency in the matter.

Accession 1 is composed of the representative sample of objects that Morris, acting as agent for the American Museum, temporarily loaned in 1927 for the display Custodian Boundey arranged in seven rooms of the ruin. These were things in storage at the American Museum field house adjacent to the monument and came from diggings done after the major excavations had terminated. Morris included items from the Annex, three courtyard kivas, and the small-scale work carried out in the summers of 1924 and 1925, as well as heavy or bulky objects from earlier clearing. The loan agreement signed by Morris and Boundey listed 261 specimens. [38] However, an inventory done in 1988 shows a total of 277 entries in Accession 1. A wrapped burial from Room 153 (F.S. 3977) is included. This increase likely resulted from Morris having added to the displays after Faris became custodian. Of these specimens, 120 remain at Aztec, with 22 listed as being at Aztec but currently missing. One hundred thirty-three specimens of this accession are at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, with two items in that file checked as missing. [39]

The remainder of the specimens obtained during phases of the American Museum of Natural History project were lumped together as Accession 8 in the monument cataloguing begun in 1934. An array of perishables, the garden-variety stone implements, pots restored since the 1920s and those not regarded as choice, batches of potsherds, debitage, and animal bone fragments are in this group. The inventory of 1988 lists 185 specimens of this accession as being at Aztec Ruins National Monument, with 21 missing. The tabulation of Accession 8 at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center is 1,424 specimens, with six missing. Together, a total of 1,636 artifacts is in Accession 8. [40]

Accessions 1 and 8, therefore, account for 1,913 American Museum specimens. A list of specimens Morris compiled about the time the monument was to be expanded to include the last of the American Museum land totaled 2,234 items. [41] The discrepancy between his figure and the current tally cannot be explained. The inadequate storage and security arrangements that formerly existed at Aztec and the number of times the objects were moved (from Aztec to Globe to Tucson) likely led to losses.

Six sequences of excavations on the monument have produced assemblages of specimens, including two burial bundles. These excavations were to clear rooms for a museum (1927), to realign the visitor trail (1938), to stabilize parts of the East Ruin (1956), to open the Hubbard Mound (1953-54), to trench a trash mound in front of the visitor center (1960), and to stabilize five rooms in the North and West wings (1984). A large return of artifacts came from Civil Works Administration excavations carried out in 1934 in connection with the cleaning up of the monument. Other scattered random finds have been made during the government's stewardship. Also in the past, private individuals donated personally collected artifacts to the monument. The majority of objects obtained in these diverse ways are or will be housed at the Western Archeological and Conservation Center, with only a small assortment being kept at the monument, where space and curatorial staff are restricted.

At the end of 1988, for the first time in the monument's history, cataloging of locally held specimens and their record keeping were brought up-to-date. A backlog of 31 large boxes of miscellaneous potsherds, lithics, bone fragments, and bits of wood, which for years had been in the administration building basement, was processed by Archaeological Enterprises, of Farmington. [42] The 1,100-plus new catalogue entries created from this effort have limited scientific value because of the relative unimportance of the materials in the total panorama of Anasazi material culture. That is why they remained ignored for so long. As a sign of the times, this cataloging of what Morris thought of as waste cost $15,000, or half the total expenditures for his six years of excavation. [43] Nevertheless, the slate at the monument is cleared of uncatalogued materials.

The approximately 60,000 specimens obtained in 1984 are being processed at the regional office in Santa Fe. This collection contains a large amount of organic material, which supplements earlier finds of the same kind of objects. The entire written catalogue file, including specimens in National Park Service facilities and the two American Museum of Natural History accessions, is being computerized using the Automated National Catalog system.

Although not as diverse or special as the collection in New York, the National Park Service assortment does afford research possibilities, such as those being undertaken by Peter McKenna. [44] In addition to supplementing data from the American Museum artifacts, some categories of objects are more plentiful in the government holdings. These include 94 projectile points, 53 grooved stone axes, and 287 bone awls, not including whatever is in the collection being processed. In regard to the distinctions between Chaco and Mesa Verde material culture, most of the finds from Kiva Q and Kiva R are available in these assemblages. Since Morris used these specimens to buttress his theory of sequential occupations, their study might be useful in segregating Chacoan diagnostics.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/adhi13.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006