|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 12: STABILIZATION: THE HIGH COST OF WATER

Aztec Ruins has been a heavily-used testing ground for substances and means to unobtrusively hold it together for the benefit of posterity against what at times have been overwhelming odds. Ironically, the principal enemy in its preservation has been an overabundance of one physical element the periodic scarcity of which may have been a contributing factor in its abandonment six or seven centuries ago. That element is water.

In the beginning of nineteenth-century awareness of the grouping of sites that now compose Aztec Ruins National Monument, it was not water that constituted a threat to their survival, but man himself. Realizing this, John Koontz, the first owner of the land upon which the ruins are situated, attempted to prohibit indiscriminate digging in the largest of the mounds or robbing them of architectural materials. This was a policy subsequently followed by Henry Abrams, who purchased the land in 1907.

While curtailing vandalism was a goal, Abrams also dreamed of having the structure beneath the mounds become a well-preserved, if not restored, attraction. He therefore included their preservation as part of his long-term excavation agreement with the American Museum of Natural History. Already having the high-minded intention of in some way making the site available to the American public, it was a stipulation to which the museum readily agreed.

Thus, from 1916 to the present, the Anasazi great house now known as the West Ruin has received constant protection. That protection has had two facets: vigilance against despoliation and reparation. Reparation has spawned a new specialty called stabilization, subsidiary to research archeology, to the benefit of all Anasazi remains within the National Park Service system.

A chronological account of the efforts to save Aztec Ruins elucidates what has become a crucial part of the management of the monument. To minimize duplication, some relevant information presented in Chapters 3 and 7 will not be repeated.

1916-1922

Once into the clearing process, the American Museum of Natural History realized that many factors posed possible threats to the security of Aztec Ruin. With so many residents of the area being avid collectors of local antiquities, it would not have been surprising if some were tempted to engage in private exploring in unguarded open trenches. Until the National Park Service appointed a full-time custodian 10 years after active exploration began, Morris or one of his associates was in residence in or next to the site. During much of that time, the area was fenced for the purpose of discouraging that sort of activity. Actually, other than initials on beams, evidence for looting or vandalism is relatively minor.

The repair of the huge structure was a more daunting obligation of required protection and would have been of even greater consequence had the museum fulfilled its original pledge to uncover the entire site. Removal of ponderous accumulations of fallen construction stones, water- and wind-deposited earth, and roots of the dense vegetational overgrowth released pressures that long had held components immobile. Once freed, some walls slumped, others fell. Some roof beams crashed downward or snapped at midsection. Their dangling stubs often pried out chunks of supporting masonry. Raw wall tops allowed moisture from rains or snows to work down into unconsolidated rubble cores, where it melted the mud that glued the mass together or froze and pushed off or ballooned the facing. These conditions made working within parts of the house block so hazardous that on many occasions Morris was forced to divert manpower and funds to repair, rather than to excavation. Stone masons became as important as diggers.

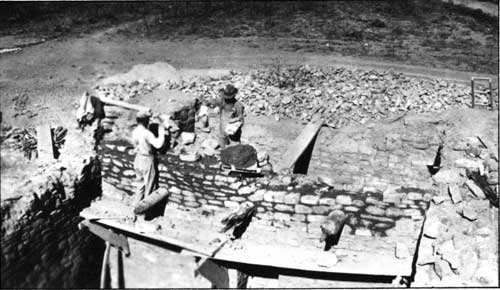

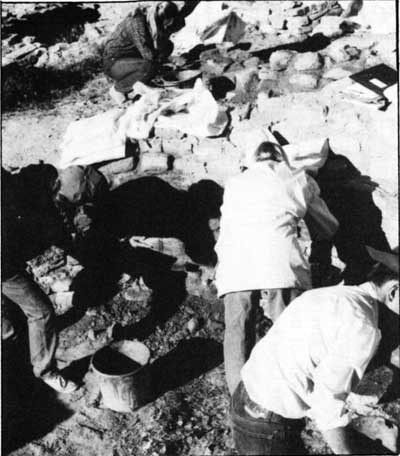

There are no records of the repair work undertaken during the period of the American Museum involvement with Aztec Ruin. Although specific chambers are seldom identified beyond notations about which sections of the site were cleared each season, Morris's personal letters, reports, and photographs do hint at the kind of measures taken. [1]

Morris's workers dismantled and relaid portions of the sandstone block veneer of many of the less stable walls using Portland cement for mortar (see Figures 12.1 and 12.2). In one season alone (1918), Morris purchased an entire boxcar of this material. The cement dried to a typical grey color and was very obvious in its contrasting color to that of the brown mud used by the original masons. It readily identified reworked sections. Many persons considered that distinction between old and new work as desirable for the sake of authenticity. In response to a later inquiry from Southwest Monuments Superintendent Pinkley about using colored mortar, Morris replied that the aesthetic effect of colored mortar would be greater than the pronounced contrast of white cement and dark stone. But he added, "If the coloring is made too close to the original earth mortar, many will not be able to distinguish between the work of the aboriginal and that of the modern masons. On the contrary the use of natural colored cement would create a condition that could not fail to be understood by anyone with sufficient intelligence to wonder about it." [2] He went on to suggest recessed mortar for vertical walls and colored cement for flat areas.

|

| Figure 12.1. View over northeast corner of West Ruin showing cement wall capping. |

|

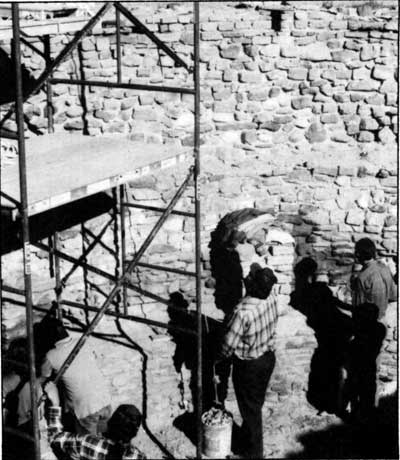

| Figure 12.2. Two views of wall repairs, West Ruin, by American Museum of Natural History crews. |

In the effort to make the modern American Museum field house as compatible as possible with the rehabilitated adjacent ruin, Morris turned to the conceit of having some of the upper courses of its new masonry set up in the natural colored concrete so that it, too, would appear to have been repaired (see Figure 4.1).

Troughed cappings of cement, designed to direct water along wall tops to drains from which it would flow away from the walls and into the courtyard, also were constructed of cement. Innovative but unsightly, they were effective in slowing wall decay until better preservation measures could be devised. At the same time, these troughs contributed to a damp plaza. [3] A fundamental flaw to use of cement was that it was not impervious and eventually water found its way through it. After cappings had gone through the first winter's exposure, Morris wrote, "The portions excavated show less deterioration than was to be anticipated, and it seems that a capping of cement will make the walls relatively permanent" (see Figure 12.1). [4]

The American Museum masons spread cement over other exposed portions of the ruin. They covered dirt-filled corners surrounding circular kivas built in rectangular spaces in an attempt to keep moisture from soaking into the soil and then into the kiva walls. After an experiment conducted in 1916 with one room, they poured concrete slab roofs over about 10 rooms, which Morris found to have original ceilings of beams of several sizes, bark, matting, and earth. [5]

Morris's report in 1918 to the American Museum recounted some of the repair activity:

For the most part the walls were in bad condition, hence a considerable proportion of the season's activities consisted of patching those that threatened to collapse, and of rebuilding those that had fallen. As a final protection against the elements, the tops of the walls of the east wing, and those of north wing as far as they have been exposed, were capped with from one to three courses of stone laid in cement, the total area of wall surface so treated amounting approximately to 7500 square feet. By way of summary of the three years' work [1916-1918], the walls of the east wing and one half of the north wing have undergone the ultimate stages of repair. [6]

Records of the American Museum annual budget set aside for repair of the Aztec Ruin are sketchy. Although at the beginning of 1920 Morris requested a sum of $800 for fixing walls, just $100 was used for that purpose. [7] In October of that same year, Morris sent in an estimate of costs to repair 10 rooms at $1,105 and to lay concrete ceiling slabs at $850, but the museum did not respond favorably. In 1921, $350 went to pay for cement slabs over nine roofs. [8]

1923-1933

In theory, the National Park Service assumed the role of protector of Aztec Ruin when it was designated a national monument in 1923. Beyond a few signs warning against trespassing and naming Morris a nominal custodian so that he would have authority to represent the government in any confrontation with looters, there was little serious attempt to fulfill that obligation. For two years, the National Park Service did provide $500 annually for limited repairs. [10] The American Museum on occasion also contributed small sums for repairs as were mandated under terms of the government excavation permit. [11] Together, these monies represented a greater investment in reparation than in the preceding excavation period.

In 1924, only $324.20 of the National Park Service repair money was spent. Two-thirds of the sum went to pay Owens, Tatman, and Hudson for work on the ruin and a week's work by a team and driver to haul off debris. Morris reported the works as:

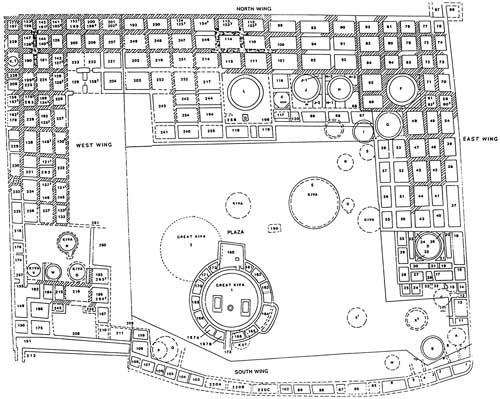

the rebuilding of the front wall of room 58, and the repair of the wall in front of this room; the repair of the cement drainage courses around Kiva G; the filling of sunken places at the northwest and southwest corners of Kiva J and recovering the same with cement; the repair of the drainage spout in the wall between rooms 96 and 120; the construction of nine cement floors for the protection of intact ceilings beneath rooms 1542, 1522, 1532, 1912, 1402, 1272, 1342, 1792, and 1332 (see Figure 12.3). [12]

|

|

Figure 12.3. West Ruin, Numbering system of 1988. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In passing this information along to the director of the National Park Service, Pinkley knew that some explanation for concrete over roofs was needed. He wrote:

Earl has found several cases where a two or three story tier of rooms have collapsed in the upper portion, but the ceiling over the lower room has held and is supporting the debris. It is necessary to take this superimposed weight off such ceilings in excavating the ruins and this leaves what was the second story floor exposed to the weather as a roof over the room below. Unless a skin of cement is run over such an exposed place and the drainage carried away, water seeps down and destroys the construction below. [13]

The same year Morris wrote Wissler of other required repairs. "In the west half of the pueblo approximately 40 rooms have been opened, the walls of which have been left as found. By strict economy it might be possible to rebuild where necessary, and to cap the walls for $30 per room, making a total of $1200, for the entire forty." [14] Again, this work was not done at that time.

While Morris was working in Yucatan in the spring of 1925, he had Oley Owens doing repair work at Aztec Ruin with the National Park Service money. Owens placed a cement covering over the troublesome roof on Kiva E, built up and capped the walls of Kiva L, and fixed various unidentified nearby room walls. He placed a cement protective slab over Room 178 and prepared the roof of Room 137 for later cementing.

Because $140.67 was left from the original $500 budgeted for 1925, Morris sought Pinkley's approval to have Owens return to a possible kiva in the courtyard. It lay deep beneath the surface to the west of Kiva E. Earlier this structure was partially dug out in hopes of finding another deeply placed deposit of Chaco pottery, but it was in such poor condition that work was halted. [15] By going some six to eight feet through its floor and then tunneling eastward to the base of Kiva E, Morris felt a drainage sump would be provided for Kiva E. That chamber already was suffering from collected moisture. When the sump was created, the unidentified kiva would be filled with loose rock. [16]

The first two full-time custodians of the monument, George Boundey and Johnwill Faris, were faced continually with the enormous job of countering damage to walls of rooms and kivas caused by heavy summer rains and winter snows. Increasingly, a previously unrecognized source of trouble was subsurface drainage from irrigated fields to the north of the house block. This moisture undercut wall bases and even dissolved the friable sandstone of which the walls were built. Remedial actions usually were the responsibility of the custodians, who spent many hours bailing out potentially destructive water and reconstructing rock and mud walls. Only under dire circumstances was it possible for them to hire part-time assistants.

Boundey tried a number of preservation measures. Although he felt that adding a terra cotta colorant would improve the appearance of redone sections, he continued the use of natural cement for wall rebuilding. He improved drainage around bases of some walls by grading, and he dug dry barrels in the floor of certain chambers to collect standing water. Boundey discovered that many of the cement-covered kiva corners had cracked, allowing water to get down around the kivas and through their walls. He removed the cement and filled the spaces with crushed rock to absorb the moisture. He observed the same problem in a few roofs erected over prehistoric rooms with Anasazi ceilings. Boundey sealed cracks in those concrete slab roofs with tar. [17]

Because of the seriousness of the threats to the ruin, in the summer of 1928, Boundey hired a man to help with wall repair. Some of the higher walls were so precarious that he reported, "they will not hold out through winter" and that "...it is a mystery to me that they had not fallen long ago." Seventy-one units were capped during the Morris years, but there remained 42 exposed rooms with no cappings.

To counter man's damage, Boundey removed almost 10,000 initials scratched or scrawled on ceiling beams. A blow torch obliterated the former, a wet cloth dipped in sand the latter. [18]

With many prehistoric structures included within the Southwest Monuments, Superintendent Pinkley was very aware of the mounting difficulties in maintaining them. He sought the first of what was to become a succession of engineering studies for means of protecting them. As he explained to the director of the National Park Service, "This whole situation of the repairs to ruins has been almost unbearable. We have been in a situation of a half dozen men trying to put out a forest fire.... Wherever we were and however hard we worked with what we had, we knew Nature was getting ahead of us someplace else." [19]

Nevertheless, funds for ruin repairs were seldom allocated. Custodian Faris made repeated pleas to his superiors for money to take care of some of the trouble spots. Local citizens tried to help by going directly to their congressmen. In 1931, the Aztec Chamber of Commerce drafted a resolution, which was transmitted to the New Mexico congressional delegation (see Appendix I). It strongly urged an appropriation for repairs to the ruins, saying they were getting in "bad condition." [20] The document brought no immediate reactions, but the wheels of government were turning slowly.

In 1933, James B. Hamilton, assistant engineer from the National Park Service's field headquarters in San Francisco, was sent to Aztec to evaluate the precise condition of the ruins from a professional point of view and to work out methods that could be taken to keep them from reverting into rubble heaps. Upon finding several feet of water standing in some rooms, walls recently caved in, and the Great Kiva virtually obliterated, he concurred with local assessments and reported that, "At Aztec Ruins National Monument much work should be done soon to prevent deterioration which is progressing rapidly there." [21] Hamilton agreed that a soft, poorly consolidated sandstone used by the settlement's builders was being destroyed by dampness. Moisture attacked walls at foundations, from where it was drawn into the lower courses by capillary action. Precipitation soaking into wall tops rotted the stone, dissolved mortar, and, when it froze, split the construction.

Hamilton also observed that some of the earlier preservation aids were not satisfactory. The concrete troughs with which Morris had capped many walls were badly worn in places due to variation in quality and thickness of the cement used and lack of reinforcing elements or expansion joints. Water funneled through the resulting cracks into the cores of walls. Some concrete-slab, secondary roofs placed over rooms with intact ceilings had split, letting water reach the perishable ceilings below. Although Custodian Boundey previously removed faulty concrete coverings from soil-filled areas around some kivas, a few such cappings remained in place. They, too, were fractured and were not keeping water from the kiva walls. Moreover, the reconstructed cribbed-log roof and its concrete-and-tar paper shield covering Kiva E were in bad repair. Some logs were rotting from the effects of moisture that penetrated the roof.

Hamilton offered many recommendations, accompanied by engineering drawings, for further monitoring of destructive forces and upgrading means for dealing with them. [22] He said that test pits should be dug about and within the ruin to see if seepage from nearby irrigation ditches reached the footings of standing walls and the sides of subterranean kivas. If so, it should be intercepted and diverted. Troughed wall cappings should be replaced by more appropriate rounded coverings of several courses of selected stone laid in reinforced cement provided with expansion joints. Tar paper bases with water-tight connection to walls topped with earthen fill should be installed in order to eliminate undermining of walls. At the time of Hamilton's inspection, there were 20 known original ceilings. In order of the urgency of repairs to the roofs over them were Rooms 143, 132, 142, 197, 198, 200, 208, 156, 141, 61, 59, 124, 189, 178, 262, 146, 237, and 263. Severely cracked cement on these roofs should be removed; those not badly damaged should be repaired. A new outer tar paper roof should be put on Kiva E but hidden from view with a thick layer of dirt. Further, in order to keep the kiva dry, a tile drain should be implanted in the bottom of a deep, gravel-filled ditch. The floors of rooms most susceptible to standing water might be paved. Perhaps a skirt of pavement extending eight to 10 feet away from the exterior walls of the house block should be considered. [23] A dry barrel should be dug into the room in the North Wing next to those housing the museum exhibits in order to collect rain water. Restoration of the Great Kiva, following a plan proposed by Earl Morris, should commence as soon as possible. Cost of necessary improvements was estimated to be $10,175, about what Morris also figured but short of the final output. [24]

In preparation for the big repair effort, Custodian Faris and Assistant Engineer Hamilton made three tests. They put down borings about 50 feet north of the northwest corner of the West Ruin. They encountered wet sand at the 12-foot level, or at an elevation of 5,630 feet above sea level. This was believed to be some three to four feet above the damp floor of Kiva E. [25] The two men also obtained two 20-pound samples of fine sand from exposed riffles in the Animas River, a sample of the monument water, and several cans of earth. These were shipped to the National Bureau of Standards laboratory in Denver. Hamilton wanted to know if the sand were suitable for the fine aggregate needed for masonry mortar, if the water were too alkaline to have sufficient strength, and what was the relative moisture content of the earth. [26]

The results of the tests were negative on two counts. The sand did not meet National Bureau of Standards grading requirements, and the water lowered tensile strength about three percent in a seven-day test. [27] The soil was of satisfactory organic and tensile strength. [28] That meant that sand had to be acquired commercially, and a water softener was needed to take care of the alkali.

In related preliminaries, Faris dug by wall bases in many portions of the pueblo to determine that their foundations did not go more than two and a half feet below the ground surface. [29] William J. Ashley, Branch of Engineering, supplied concrete specifications for capping the walls. [30]

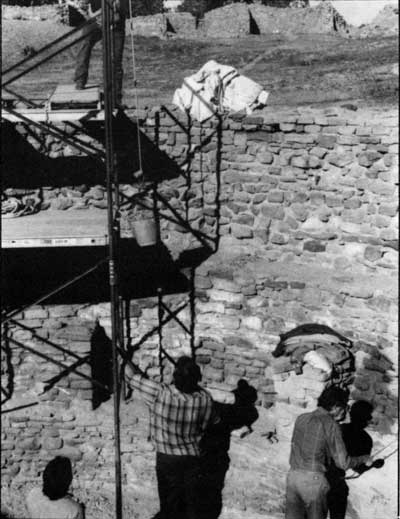

1934-1936

As outlined in Chapter 7, between 1934 and 1936 some ruins repair was included in general clean-up and refurbishment, trail building, and flood-control activities under government relief funds. A major project of that time was the rebuilding of much of the outer north and west walls of the pueblo. This was made necessary when, during removal of debris from the exteriors of those walls to better delineate the ruin, it was discovered that they were in very poor state of repair. Therefore, Public Works Administration crews, with Morris acting as supervisor, gradually razed and rebuilt large portions of this part of the West Ruin. Morris cautioned the crews to be careful not to add to or subtract from what was actually existent when first discovered. Workmen reset stones in their original position using cement mortar and replaced some rotten wooden elements. In the North Wing, they removed untinted cement cappings and replaced them. To make the mortar less noticeable, they carefully pushed it well back of the rock facing.

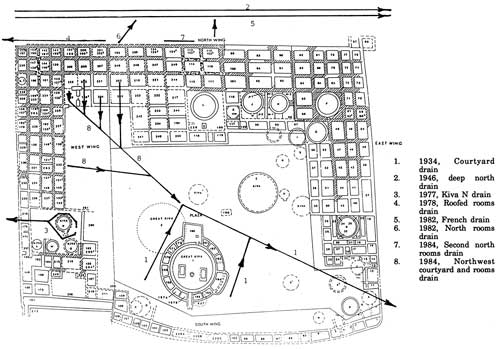

Concurrent with the wall rebuilding, other laborers made an attempt to prevent ground water from getting into roofed Kiva E, the Great Kiva, and additional subterranean features by laying a subsurface drainage system in the courtyard of the ruin. [31] The plaza drainage system consisted of a 10-inch tile drain placed next to Kiva E at a depth of approximately 17 feet (see Figure 12.4). It had underground branch lines radiating outward, including several drop inlets to interrupt the normal surface runoff within the courtyard. When the Great Kiva was restored, its considerable roof runoff was channeled into the primary line. Although it was reported to deliver approximately 200 to 250 gallons of water every 24 hours, the drain became progressively ineffectual and ceased to work altogether in early 1938. This was due to blockage of the main line by mud and vegetation, breakage of tiles, and the very slight gradient of the outflow. [32]

|

|

Figure 12.4. Schematic plan of major drains, West Ruin. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Hamilton designed and installed an experimental type of reinforced concrete roof over intact ceilings of two rooms. Modeled after a comparable experimental roof already in place in Pueblo Bonito, they were meant as catch basins where water would evaporate in place. [33] After Hamilton tried to patch several of the concrete covers fabricated by Morris, he concluded, "It is certain that the old concrete covers will have to be removed and entirely new covers built."

Engineers drew designs for additional projects. Among these were recapping the triangular spaces around kivas within the room block, providing air vents through the kiva walls, and setting the cap onto walls rather than the dirt fill. [34] They prepared a plan for reroofing Kiva E, which still had its old Morris wood, tar paper, and cement cover, with a new reinforced cement slab raised a foot above four girders.

Because the Great Kiva reconstruction absorbed the allocated funds, these various contemplated repairs remained in limbo but gradually were incorporated into an evolving 10-year program for protection of Southwestern ruins. [35] Previously in the early 1930s, Pinkley asked Faris to develop a six-year repair plan for the monument, but it was lost in the flood of developments made possible by federal relief programs. [36]

Because of his experiences during the Public Works Administration programs at Mesa Verde and Aztec Ruins, Morris favored a permanent plan for ruin survey within the National Park Service holdings synchronized with an annual schedule of repairs. His qualifications for an individual to head such an endeavor included a range of skills such as had not been generally cultivated in the new field of ruin stabilization, other than in Morris himself. As he wrote the director of the National Park Service, a person to lead this important task should have "practical commonsense, intimate familiarity with and understanding of the material used by the ancient builders, wide and penetrating observation of original methods of construction, a working knowledge of masonry technique, an eye to aesthetic effect, and intense interest in the work at hand." [37] These qualifications were in addition to a great deal of actual experience.

By the summer of 1935, something had to be done about the wetness of Kiva E. The idea of the moment for correcting this situation was a fan to circulate air. Investigation by Faris revealed that he could procure a 12-inch exhaust fan for about $32 to $100. It could be installed by the kiva's ventilator shaft or framed into the roof. His financial account had neither the necessary balance for such a purchase nor funds to cover the electric bill that would result from continual use of the appliance. An alternative was a sump pump operated by a float switch, but this was more costly. The third idea was to install tile drains within the kiva connecting to the main courtyard drain. That would have meant removing and rebuilding the hearth and ventilator opening. Besides, the primary drain outside the kiva already was showing signs of becoming useless. [38] Faris decided to try a fan specially built with motor and blades fashioned to his particular needs. How he financed it is unknown. For a time, the fan seemed to help dry out the chamber. [39]

Meantime, National Park Service engineers went to work on the basic problem of seepage. They drafted Plan AZT-4958. It called for excavating into the floor of Kiva E to reach the primary court drainage line, laying soil pipe and fittings in a gravel and sand bed, and backfilling the trench. This could be done at a cost of $375. [40] Even though Chief Engineer Frank A. Kittredge had included Aztec Ruins National Monument in his general request of the previous summer for $150,000 for protection of Southwestern ruins, there was no money to carry out this particular job. [41]

Troubles mounted during the winter of 1936, as, with a single exception, all the protective roofs over Anasazi ceilings failed. Faris did what he did with regularity: he sent off a request for a supplemental appropriation for ruin repairs. He got his usual reply. Hugh M. Miller, then acting superintendent of Southwest Monuments in Pinkley's absence, curtly said that since the monument had received a large sum for that purpose as recently as two years previously, the request would be met with a cool reception. Miller continued, "It is going to be a little awkward to explain to the Secretary that we had the money but spent most of it for restoration of the Great Kiva and neglected urgent work on the main ruin." [42]

Faris persisted with a following letter to Pinkley, explaining that eight or 10 roofs simply had to be repaired at once and the remaining 15 shortly thereafter. He hoped perhaps another contingent of Civilian Conservation Corps youths could be put to work on damaged walls, if only somehow $500 could be found. [43] In hopes of favorable response, he obtained a print of Engineer Hamilton's plan (AZ 4950) for placement of roofs over original ceilings. [44] Since Faris's request of March was met with silence, in June, he forwarded to Superintendent Pinkley yet another one for repair funds. This time the amount was set at a whopping $7,400 to pay for 20 catchment-type protective roofs, reroofing Kiva E with the reinforced cement covering designed in 1934, and a protective cement roof over Room 117 with incised murals. [45]

On August 30, a two-inch downpour engulfed the monument within an hour. One can feel the tone of despair as Faris lamented to Pinkley, "There is about five inches of water in our roofed kiva [Kiva E], several walls fell in and the bench around our show kiva [Great Kiva] where the logs were exposed which contained the offerings is falling down at an alarming rate. The big drain trench settled in several places leaving large holes, low places are filled with muck and stagnant water. The whole place carried a terrible odor from the mess and weeds have popped up six inches in the past two days." [46] To top it off, the fan in Kiva E was drowned and destroyed. Five unidentified Anasazi ceilings were repaired shortly before the storm; the remainder held. [47]

Engineers from the San Francisco office determined that so much water rushed down or over the roof spouts of the Great Kiva, some of which were plugged, that the court drain was unable to carry it out of the area rapidly enough to prevent it from backing up into Kiva E. [48]

1937-1942

Within a few months after his appointment as custodian in 1937, Thomas C. Miller began the same litany of hopelessness, followed by small repairs and requests for more financial help. That winter was especially hard on the ruin, causing sections of 42 walls to topple and up to 25 inches of water to stand on the dirt floor of Kiva E. Because current policy was against any sort of surfaced path, visitors either had to wade ankle-deep in mud across the courtyard or not view it. [49] Miller borrowed a pump and fire hose from the city of Aztec to get the water out of the kiva, after which he set a two-burner oil stove in the chamber to help dry it. [50] Southwest Monuments gave Miller $100 for emergency work, but that had to be shared with Chaco Canyon, where crews were busy cleaning debris and ancient rip-rap from behind Threatening Rock. [51] With that money, two laborers were hired to mend unstable walls, reroute the drainage around Kiva E, and waterproof roofs protecting the aboriginal ceilings in five rooms. [52]

Miller's helpers just had time to finish righting the wrongs of one period of devastating weather when another struck. During July, 1 1/2 inches of rain pounded Aztec Ruins in a half hour. Not only were the ancient chambers battle scarred once again, but modern roofs on the restored Great Kiva, the administration building, and the custodian's residence leaked like sieves. [53]

Looking to the future, Miller suggested some possible preservation measures. He thought it might be wise to pour concrete footings beneath the bases of the more critical walls and then secure the second and third floor structures above them. Although he and Engineer Kittredge were concerned that their mere installation might weaken walls, Hamilton endorsed the idea of cement footings. [54] Miller also recognized the ineffectiveness of the heavy, pervious, cement-slab roofing over prehistoric ceilings and recommended that any future plans to insure their conservation consider built-up roofing of wood and tar paper. [55] In April, he sent in a request for $10,415.90 for the frequently recited jobs of protecting ceilings, caring for the roof of Kiva E, filling the spaces between round kivas and square rooms, and patching walls. [56]

It was during the same year of 1937 that the National Park Service at last acknowledged the necessity of approaching ruins repair in a more systematic fashion if it were to meet the charge to save its Southwestern archeological holdings from destruction. It was an idea that had been simmering throughout the decade, but now a formally organized team was authorized to devote its time and energies to this specific endeavor. With that action, the word stabilization and the concept it represented of strengthening aboriginal architectural remains as inconspicuously as possible to endure the future -- but not reconstruct them -- became part of the Southwestern archeological creed.

The new ruins repair effort was set up as a program under the Civilian Conservation Corps by agreement between the National Park Service and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. [57] The National Park Service provided materials, equipment, and supervision of a person well grounded in regional archeology who also had demonstrated some practical construction skills. The Navajo Agency supplied a crew of 25 Native American enrollees to work out of a base camp in Chaco Canyon. For five years, the unit moved between 14 Southwestern monuments containing aboriginal structures of various sorts doing both emergency and routine maintenance stabilization work as required. The number of Navajo participants decreased to 20 in 1938, then to 10 in 1940. Between 1942 and 1946, the Civilian Conservation Corps Mobile Unit was disbanded because of World War II. [58] When reorganized, Navajo workers were joined by other minorities.

Although for many years their procedures necessarily remained on a trial-and-error basis, the Navajos enrolled in the first program soon jelled into an efficient group of stone masons. Their early work was at Chaco Canyon and Aztec Ruins, where constructions rapidly were falling into disrepair because of many of the same environmental reasons. However, the damage from underground water was peculiar to Aztec Ruins. The compromise between sound building methods and authenticity in appearance was a constant challenge. The policy became one of retaining the look of Anasazi architecture as it was found upon excavation, while calling for reinforcement on such modern chemical products as would not alter that. A systematic inspection of ruins and a standardized style of documentation of remedial treatment were instigated so that future technicians would be enabled to distinguish original from treated constructions and know how to proceed. [59] Stabilization advanced from repairs done after the fact to setting up long-range plans to deal routinely with unstable ruin walls and to observe them over time to prevent, rather than fix, damage.

From 1938 to 1942, the Civilian Conservation Corps Mobile Unit did intensive stabilization at Aztec. Although Archeologist Vivian was general supervisor, Custodian Miller actually directed the crew at Aztec until the winter of 1941-42 because of Vivian's involvement elsewhere. [60] Miller discontinued the use of natural cement. Instead, the Mobile Unit adopted the practice of adding bitumen, an asphalt derivative, as waterproofing to mud mortar for wall capping and laying walls. Initially, the consensus was that this combination of substances was satisfactory and better looking than earlier mortars.

During 1938 and 1939, workers gave special care to the West Wing and the southwest corner of the ruin. The Indian crew redid walls of 14 rooms with heavy integral capping reinforced by bitudobe to replace the old gutter caps. They covered six Anasazi ceilings formerly having cement-slab roofs with a two-inch waterproof layer of bitudobe.

At last, Kiva E was reroofed. Laborers removed the old outer lumber-and-tar paper roof and the concrete slab covering it. They tamped a soil bitumen plating in place over the native soil and cribbed logs and applied a topping of sand. As a final touch, they raised the masonry of the outer wall above the roof level, with weep holes added for drainage. With Vivian giving the cost of materials as $25, one wonders why the replacement of the roof had been postponed for so many years. [61] The men eliminated an unsuitable wooden railing leading to the ladder in the kiva hatchway.

Elsewhere in 1939, workmen sunk tile drains in several rooms to gather and direct surface water away from the ruin. They repaired Rooms 249, 202, and 193 after their excavation by Archeologist Steen. [62] Finally, the men painted the Great Kiva roof with bitumuls and then rolled it with sand. [63]

At this time, the numbering of some rooms on the map used in preparing early stabilization records became confused. The map was based on Morris's map of 1919 without realizing it had been amended in 1924 and 1928 to include the later excavations. Therefore, stabilizers scrambled numbers of rooms that already had been numbered and added new numbers to this error-ridden base as their own work progressed (NM/AZT 5301). The record is particularly confused for the northwest corner of the compound and the West Wing chambers. Numerous attempts have been made since the 1950s to correct the mistakes, most recently by Todd R. Metzger of the Southwest Regional Office in Santa Fe (see Figure 12.3). [64]

While Vivian's men were busy with repairs to the West Ruin structure, Miller continued to struggle with the destructive drainage problem. He and his rangers dug down to the courtyard drain put in just four years earlier and found that tiles were crushed, collars were disconnected, and exposed sections were blocked by the mud and straw of the trench fill. Furthermore, the outlet was plugged with rock and soil. [65] All the work, money, and near death of one laborer to lay the drainage system apparently were for naught.

Various stabilization efforts continued in 1940. Crews made repairs to Kiva K, which endangered the visitor trail, and to Kiva L. Workers rolled the plaza surface and former ruin museum floors to compact them and reduce erosion. Custodian Miller remained anxious, as he reported, "...we still have about 300 rooms that have had no stabilization and unless treated at an early date, deterioration is certain." [66] The number of chambers was exaggerated, but the problem was not. Miller was given $300 for repairs, but he replied that he really needed $1,000 over several years. [67] In November, Southwest Monuments added $100 to the Aztec Ruins National Monument stabilization account. [68]

That fall, in response to a survey by Southwest Monuments of repairs needed to all the ruins in its jurisdiction, Miller reported 226 rooms and 19 kivas excavated to December 1940, 45 rooms and two kivas with protective wall capping, all rooms with aboriginal ceilings waterproofed, and courtyard graded and drained. That represented 24 years of hard, and often frustrating, labor. Miller estimated 179 rooms still needing capping and 250 square yards of wall requiring patching. [69] Although it was realized that it would take many additional years of work, Miller's stabilization budget then had a balance of $19.02. [70] It was obvious that any further repairs would have to be delayed.

Into the next year, the ruin continued to crumble down around the hapless monument staff. As relief ranger Ed Albert said, "...ruins may be seen falling before one's eyes...hardly a foot of uncapped wall which has not suffered serious damage. In the southwest wing of the pueblo, a huge section of wall and door have collapsed." And he sent forth another fruitless cry in the dark, "Stabilization is urgently required." [71]

Meantime, because in January tons of cliff known as Threatening Rock crashed down upon Pueblo Bonito, the Civilian Conservation Corps Mobile Unit had its hands full. It was not until September that the crew could return to work at Aztec Ruins and then only on 29 affected rooms and three kivas. This schedule took the men through the winter and the start of World War II.

Because the Mobile Unit was disbanded in April 1942 for the duration of the war, just one or two Navajos continued to work. They patched walls in the North Wing that could not wait until the fighting stopped. They reset walls of Kivas H and J and improved the drainage around them. Miller asked for $48 to have the Great Kiva roof waterproofed but was told that the monument account had a balance of only $39.68. [72] For the lack of less than $7.00, the structure was doomed to leak. However, the next month Southwest Monuments came through with another $125. [73] Regardless of this token allotment, ruins repair at Aztec remained understaffed and underfunded. With warfare raging around the world, Aztec Ruins was on the brink of its own archeological skirmishes and the soldiers were the custodian and his two rangers, Russell L. Mahan and R. Madson, who were drafted into stabilization duty ordinarily performed by the Mobile Unit.

1943-1947

Leakage of the Great Kiva roof became so substantial during spring thaws in 1943 that the Southwest Monuments administration was able to secure emergency monies for a reroofing job. Miller submitted a job justification amounting to $250, but the final bill came to $328. [74] Miller and his helpers followed a process of filling larger cracks with cotton membrane and painting lesser cracks with a heavy-duty coating called Zone. They then spread asbestos felt around the circumference of the roof up on the parapet wall. Flashing material held in place with hot asphalt sealed the juncture of roof and parapet. Workers laid asbestos roofing over the entire roof and covered it with a hot asphalt layer. When this surface dried for several days, they applied a final coat of Zone to make the roof leak-free. [75] Or so they hoped.

Other unending difficulties besetting Aztec Ruins worsened until, in September, Miller again called for help. He and the rangers were regularly bailing out subsurface water percolating into Kivas E and I. This amounted to 200 gallons daily in Kiva I and 350 gallons daily in Kiva E. Some interior walls of Kiva I gave way, making the support of a later house wall that crossed it very uncertain. Damp spots appeared on the floors of the vaults of the Great Kiva. The men feared that it was just a matter of time until the primary flow of water worked its way southward into that structure. Bases of room walls along the North Wing, where dry ground conditions earlier were typical, were disintegrating from moisture. After an inspection by Steen, the staff decided that electric pumps placed in pits in the floors or ventilator shafts of the waterlogged kivas might be the answer. Unfortunately, the pumps failed to draw out sufficient water standing next to the lower courses of weakened masonry walls. Next, the determined rangers repaired a leaky flume on the Hubbard farm just below the Farmers Ditch. That did nothing to halt seepage within the compound. This was followed by their digging three six-foot-square pits outside the north exterior village wall, which were sunk to depths from 13 to 21 feet. A secondary hole in the easternmost pit went down 42 feet before hitting hardpan. [76] Pumps lowered into two of the pits operated around the clock. Working together over a two-month period, the pumps, helped by cessation of the irrigation season, caused a slight drop in the water table level. Kiva I began to dry, but Kiva E remained flooded. Its walls were saturated. Salts formed a deposit on the roof timbers. An emergency sum of $900 was expended without beneficial results. [77]

In 1944, several studies were done by various National Park Service officials and drainage and soil experts from the Soil Conservation Service in Albuquerque to determine the exact nature and scope of the environmental problems afflicting Aztec Ruins and how best to resolve them. The volumes of data produced merely confirmed earlier beliefs: the source of the distressing subsurface water was from the north and northeast of the ruin, where a major unlined canal and irrigated fields existed. Topography and soil conditions contributed to the difficulties. [78]

According to Jesse Nusbaum, one of those studying the matter, there were two natural and two man-caused reasons for the adverse conditions, which seemed to have suddenly become so much worse. The year 1942 was one of drought in the Southwest, with Aztec Ruins recording a low precipitation of slightly over six and a half inches. This followed an unusual high in 1941 of 23.59 inches. With the local aquifer having its source in the high elevations of the San Juan Mountains to the north, Nusbaum theorized that the greatly increased volume of moisture in 1941 took 12 to 18 months to descend 50 miles of intervening, uptilted, sedimentary formation to abruptly reach the 5,600 foot elevation of the monument about August 1943. Coincidentally, during the spring of 1943, the Farmers Ditch was more thoroughly cleaned than at any time in years. This cut out the lining of water-deposited clays and silts that inhibited seepage. Natural loss of water through the earthen canal walls and floor, added to irrigation during the summer growing season and a plethora of rodent burrows, spelled trouble for the ruins situated downslope at a point where the soils became less porous and interrupted the general southeastward flow of underground water. [79]

The most practical long-term solution these studies proposed was one to provide an adequate primary drain or cutoff along the northern boundary of the monument. The consultants believed the drain would lower the water table in the preserve below the depth of the floor of Kiva E, its deepest known structure. The proposal (AZ-M-6) was adopted, to be implemented after the war.

Meantime, Miller submitted another job justification calling for an expenditure of $1,324.75 for temporary ruins drainage, stating that the entire monument land was becoming a quagmire and corrective action was needed immediately. [80] It took three months for the Washington office to return a $1,300 allotment. [81]

Miller planned to add eight wells to the three previously dug north of the ruin. The wells, 18 feet deep with a two-foot sump, were to be 20 feet apart and set within four-foot-square wooden boxes. Miller hoped they could be incorporated into the permanent system when it was installed. Rough-sawn wood for some of the cribbing was transferred from Gran Quivira. [82] Other timber was secured from local saw mills. In spite of the urgency for action, work was delayed. One of the Navajo laborers suddenly enlisted in the army, and the second prospective helper was busy herding sheep. But by the end of April, construction of the wells began. Within several weeks, the farmer of the cornfield just to the north turned water into his fields, and all the wells on the north monument boundary promptly began to fill. One that had not yet been timbered was a total loss. [83]

When the wells finally were completed, they were connected by pipe so that flow of ground water was led to a central well. From that well, the water was pumped into an irrigation ditch to the west of the monument. Acting Custodian Mahan reported that the flow into Kiva E had not increased. He was optimistic that the latest effort would be successful. [84] But that was not to be. The wells proved one thing: that the underground water was a very complex phenomenon, which likely would need a different system than the planned permanent drainage line.

When Irving D. Townsend arrived in September to assume the monument's superintendency, he wrote eye-witness accounts of the dire state in which he found the West Ruin. In one, he recounted the well-known troubles at Kiva E and stated that considerable portions of Kiva I were caved in. [85]

Three weeks later Townsend desperately notified the regional director of the danger to Aztec Ruins. A cloudburst and hail storm dealt another severe blow by filling one of the wells with sand and silt. The pumping equipment was flooded out as a wall of water poured down the depression between the West and East ruins. In the house block, rocks fell from walls, the ventilator shaft of Kiva E half filled with water every 24 hours, and the south village wall was undermined. He continued, "Numerous leaks have appeared in the original roofs of the rooms through which tours are conducted, allowing water to seep down the walls, drip from the cross beams and generally to expose considerable roof timber to water seepage." [86]

Townsend also called attention to a problem that was developing in respect to the use of bitumen additives to mud mortar for ruins repair, a practice begun with high hopes in 1938. Although at first effective, after a period of years the asphalt-fortified mortar began to disintegrate. By the late 1950s, its use would be stopped.

Shortly after the flood of October 16, Louis R. Caywood, recently custodian at Tumacacori National Monument in Arizona, made a visit to Aztec to inspect the damage. While there, he repaired or replaced the protective roofs over six North Wing rooms and extended the pipeline from Kiva E, which took water out of the plaza. Complying with Caywood's recommendations, Townsend replaced the roof over mural Room 117 by using four-by-four-inch timbers, new felt, and bitumuls. He began a program of rodent control and saw that all short drains and gutters were cleaned. [87]

In 1944, government officials looked ahead to what would be needed for the preservation of aboriginal ruins within the National Park Service system once the war was over. A call went out for statements showing comprehensive stabilization necessary under a Major Repair and Rehabilitation Program (also called Comprehensive Post-War Stabilization Program) outlined by Acting Director Hillory A. Tolson. The Southwest Regional Office solicited statements concerning interim work necessary to carry regional sites over until the larger endeavor could get started. [88] Mahan estimated $3,900 would be required for work in the East Ruin and northeast corner of the West Ruin and in Kivas I and F. He suggested that the damaged Kiva I be backilled, using some of the dirt left from digging the drainage wells. [89] He further stipulated that $300 should be spent in backfilling the northwest sector of the East Ruin, where exposed walls were disintegrating, and in bracing sagging beams of intact roofs there. [90]

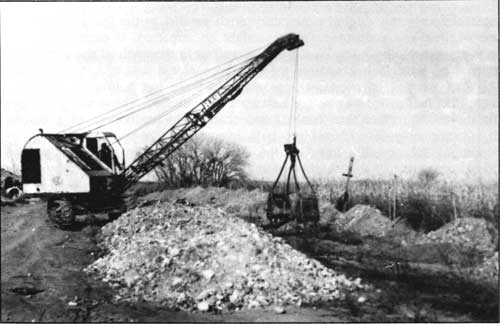

The major project for 1945 was preparatory work for installation of a deep north drainage system as outlined by National Park Service Engineer James R. Lassiter and seconded by Roy S. Decker of the Soil Conservation Service. [91] Crews removed shoring timbers and pumping equipment from some of the temporary wells and located sources of gravel to be used to fill the trench. Townsend sought laborers, who were scarce because of the war. [92]

An archeological crew dug an exploratory ditch parallel to the line of the proposed drainage system to see whether any prehistoric features might be impacted. It extended along the northern boundary of the monument above the West Ruin, as well as to the north of the unexcavated East Ruin. The only evidence of aboriginal occupation the men encountered was what was described by Ranger James A. (Al) Lancaster as an oven-cist approximately three feet below the surface. The dragline bucket cut more than half of it away before Lancaster was notified. The drawing he made at the time provides little information other than cobbles and charcoal in the bottom of a domed structure of burned earth approximately 30 inches high. It is impossible now to know if the cist might have resembled some pits subsequently found at the Hubbard Mound in the same general part of the monument. [93] Lancaster reported the area free of antiquities that might be harmed by the drainage line. [94]

In preparation for the drain, pipe and manholes were stockpiled. [95] A power shovel was borrowed from Mesa Verde National Park and parked at the gravel pit. There, it was used to dig gravel and load it into trucks for hauling to the construction site. When sufficient gravel was accumulated, the shovel was moved to the ruin and modified into a dragline. Another dragline was provided by the Soil Conservation Service. [96]

During the summer and fall, the trench digging, manhole construction, and laying of pipe progressed slowly, hampered by mechanical breakdowns, labor shortages, and cave-ins (see Figure 12.5). As stories circulated of the mishap in the courtyard trench, laborers were reluctant to get into this trench. [97] On occasion, Superintendent Townsend, in such poor health that he resigned prematurely from the Service, was forced to operate some of the heavy equipment. [98]

|

| Figure 12.5. Dragline digging deep north drainage trench, 1946. |

Some 17 months after trenching began, the project was finished on May 21, 1946. A Soil Conservation Service bulldozer backfilled the trench. Shortly afterwards, Townsend judged that the drain was functioning. A small stream of water, which increased following irrigation of fields above the ruin, ran from the end of the drain. Kiva E was drier than it had been for two years. Moisture building up on subterranean walls of the Great Kiva disappeared. [99]

Upon completion, the drainage system represented an outlay of $8,000. [100] It stretched 1437.2 feet from west to east between the monument and private land to the north. At the bottom of the trench, varying in depth from seven to 21 feet, a tile drain six inches in diameter intercepted the subflow and conveyed it to the northeast corner of the monument. There, it emptied into a waste ditch, flowed through a culvert under the county road and down a natural drainage channel to the Animas River. A series of nine manholes along the line permitted inspection of the drain and a way of flushing it if necessary.

Two months after being declared operational, the east end of the drain was filled with mud and fine gravel. Crews placed a pump in the last open manhole to keep that part of the line clear. [101] Soon, about 300 feet of the opposite end of the drain also was stopped up. For the remainder of the year and until the spring of 1947, work on the system continued. Additional manholes were built to gain access to the nonfunctioning section of the line. Because heavy equipment to clean out the line was not available, various kinds of probes and reamers were tried. All efforts failed. At last in March and April, a coordinated effort between the monument staff, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Water and Fire Departments of Aztec and Farmington succeeded in getting a traveling nozzle to force water under pressure into the lower end of the blocked pipe. The drain was kept open after that by frequent flushing. By September 1947, the water table beneath the ruins had fallen dramatically by almost four feet. [102]

During April 1945, while one crew was engaged in the drain project, Ranger Lancaster, aided by workers including Sherman Howe, carried out some emergency stabilization of walls of 22 rooms and three kivas and worked on protective roofs over Rooms 112, 59, and 156. Decaying wooden lintels in some doorways were replaced. [103]

Al Lancaster, off a bean farm in southwestern Colorado and without academic training in archeology, had years of practical experience on the excavation crews of Paul Martin, Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, J.O. Brew, Peabody Museum of Harvard University, and the National Park Service at Mesa Verde National Park. At the latter post, he worked for a time under the direction of Earl Morris. A soft-spoken, humble man, Lancaster went on to become a legend in Southwestern archeology for his keen insight and sound excavation and stabilization methods.

The next year, 1946, much needed stabilization of upper portions and tops of walls and around doorways continued in 39 rooms and three kivas. Stabilizers sloped the area outside the north exterior wall of the pueblo to carry surface water away from the wall. [104] Lancaster was field director; Erik K. Reed and Dale S. King were his supervisors. Reed greatly underestimated the dangers facing the site. He informed the regional director that the problems with the West Ruin structure were small. [105] This was an opinion at odds with that of Superintendent Townsend, who noted the continued rotting of wall bases and loss of wall facing.

Even with the deep north drain operating, Kiva E was subjected to moisture-induced erosion. Workers rushed a pump with electrical motor into action. Archeologist Reed objected to an above-ground cable strung across the front of the ruin and a highly visible discharge pipe to the southeast corner of the compound. Then, the men tried other ways to dry the kiva. All were unsuccessful. Finally, there was no alternative: the roof was removed. [106] Not long afterward, improved ventilation and exposure to the sun ended the soggy saga. The roof was in place exactly 30 years and allowed visitors to observe how a clever cribbing without use of nails, tenons, or other fasteners spanned a circular structure. But given the uncontrollable factors, it proved detrimental.

Meanwhile, another maintenance difficulty developed at the Great Kiva. In 1943, the roof was stripped of its old felt sheathing and the roof redone. However, it continued to leak almost every summer through the 1940s.

In 1945, a potentially more dangerous situation at the Great Kiva was reported by Lancaster, who happened to be in the structure with a group of visitors during a high wind storm. He noticed that the velocity of the wind generated so much pressure that the entire hatbox-shaped superstructure was lifted up slightly from the supporting members. When the pressure was released, the roof cap settled back into place with a resounding jar that cracked plaster. Later monitoring indicated that vibration of the building was not uncommon during strong winds. The Anasazi designed their massive roof-supporting columns so they would not be rigid, one must assume with knowledge that some accommodating flexibility was essential to counter movement of the building. However, the inflexible roof itself surely posed problems for them, as it did for modern preservationists. Perhaps their solution was the same as for the National Park Service architect: add more external weight to the roof. For the Anasazi, it was extra basketfuls of earth dumped over it; for stabilizers, it was soil weighted and impregnated with chemical bitumuls. [107] That modern procedure unfortunately did not work.

An architect from the regional office found that the sub-roof was earth, over which the two-by-four-inch framing had spans of too great a length. Nor was it fastened down at enough points. Also, the sheathing had shrunk. As a consequence, the roof structure was shaky. He recommended removal of the sheathing, addition of more two-by-fours of shorter span, and the entire roof be relaid. [108]

With the physical condition of the ruin continuing to decline in 1947, Reed again appraised the stabilization needs of Aztec Ruins to be minimal. A bit of loose veneer, a few wall bases in the southwest corner, the leaks in the Great Kiva roof, and water standing on the floor of Kiva E nevertheless were noted in his report. [109] No repair followed, other than removal of the roof of Kiva E.

1949-1956

For the first quarter century of National Park Service stewardship of Aztec Ruins, the care and preservation of the West Ruin consumed so much time and money that the sister East Ruin was unattended, except for backfilling some rooms in 1946. The probability that underground water from a pond and adjacent cultivated fields might be rotting both structure and any perishable artifacts it contained prompted Vivian to put stabilization funds and energies to work at the East Ruin as soon as the Mobile Unit was reestablished following the war.

During a spring month in 1949, Vivian observed that conditions of ceilings in 14 East Ruin rooms he entered varied from good, to those where beams were cracked but had not caused displacement of the ceiling, to bad where removal of beam sections let down large parts of the ceiling. In several other rooms examined, he found that ceilings were so porous that rooms below were almost filled with debris sifting downward. In such instances, he made no attempt at preservation. In Rooms 1 through 14, the Mobile Unit supported weakened beams with vertical timbers and screw jacks set on concrete blocks, plugged holes in walls, and improved ventilation in connecting Rooms 6 through 14. The men erected two wood-and-tar paper roofs above four aboriginal ceilings. Vivian was relieved to observe dry conditions in the lower portions of the house block. [110]

Stabilization of the West Ruin by the Mobile Unit was resumed in 1950 after a three-year lull. Archeologist Aide Raymond Rixey undertook rehabilitation of large sections of the North and East wings. This began what might be considered the modern period of stabilization of the main ruin. The destructive problems were identified and continued relentlessly year after year. Only their intensities varied with fluctuating environmental circumstances. Methods to counter them settled into a cyclical pattern with no end and no beginning: removing, replacing, resetting, regrouting, recapping, and then repeating. As soon as one section of the structure seemed restored to a satisfactory state, another section fell apart. As new products promising holding power appeared, they were used, and after a trial period, generally were rejected in favor of a new generation of other products. Stabilizers slowly lost ground.

Well-intentioned efforts to keep the Anasazi house block together also shortsightedly steadily altered its aboriginal appearance. Some wall openings, such as vents for air circulation, shelf-pole or ceiling beam sockets, or storage niches were sealed to create smooth veneers having reduced amounts of chinking. Over the years, such changes were so poorly documented that future researchers had increasing difficulty in determining what had been Chacoan or Mesa Verdian work and what was that of the modern masons.

The season of 1950 marked the first attempt to correct the deterioration of wall bases by removing soft and decomposed stones. The men filled undercut areas with concrete containing Hydropel, a waterproofing compound. They patched and capped precarious walls with mud mortar strengthened with bitumens. They cleaned and rerouted existing tile room drains. [111]

The following year Archeologist Roland Richert directed the reopening and stabilization of the single-tiered rooms of the cobblestone or mud-and-stick South Wing. This portion of the site remained backfilled after its excavation by Morris, who considered the walls too weak to be left free-standing. By the 1950s, the monument staff believed that opening up the South Wing would improve the appearance of the ruin and allow visitors to understand the entire ground plan. Workmen reset loose cobbles in mud mortar fortified with yet another product. This was soil-cement, a calcined mixture of clay, limestone, and earth. Masons refaced mud-and-stick walls with fresh plaster made from a combination of the same ingredients.

Other work during the season of 1951 was in the East Wing, where crews repointed or recapped walls of 45 rooms and two kivas. They reworked 27 North Wing chambers with a mud-bitumen mortar. Some men were assigned the job of removing troughed, or gutter-type, concrete cappings fashioned by Morris's farm hands and replacing them with crowned, waterproofed caps. Still other laborers poured water-resistant concrete foundations under badly eroded wall bases. They replaced missing wooden lintels. They mended cracks in protective concrete slabs poured over tops of three rooms with original ceilings. [112]

Because of the large-scale endeavors of the years 1950 and 1951, Vivian believed Aztec Ruins was brought to a state where only the Great Kiva roof needed attention in 1953. Nevertheless, those in the stabilization program worried about ceilings suffering from moisture and excessive weight. In the largely unexcavated East Ruin, Richert found main supporting beams in two rooms broken. He repositioned them and braced them with tubular steel jacks resting on poured concrete foundations. Although he also recommended that tons of fallen upper-story debris be taken off rooms with ancient ceilings and that lightweight wood-and-tar paper roofs be substituted, this was not done. Nor were deteriorating East Ruin walls repaired. [113]

During the season of 1953 in the West Ruin, Richert took charge of giving renewed protection to 16 rooms with weakened ceilings or roofs. Morris and Hamilton constructed concrete slab roofs over these rooms between 1916 and 1934. Later, a variety of materials, such as tar, sand, bitumens, and large amounts of earth, periodically were applied to the slabs to stop leaks. The net result in most cases was to add extra weight to an already heavy structure, causing the original large roof elements to bend and break under the strain. To expose the concrete roof slabs, Richert removed the overburden of dirt and other materials, which sometimes weighed as much as 20 tons. Before reroofing, the crew strengthened walls of the rooms below and capped them where necessary with bitumen-enriched mortar. New roofing consisted of three layers of asphalt felt mopped with tar. Workers sealed junctures between walls and roofs with asphalt-impregnated fabric coated with tar. They rolled fine-grained gravel over the final tar application. Wherever possible, they set large, galvanized metal trough drains in walls flush with new roofing. Roofs were sloped properly to drain into them. The workers resurfaced and repointed a partial roof of tar paper and wood over Room 117 so that it would not be conspicuous from the courtyard trail. Richert speculated that the new roofs would last for 10 to 15 years.

A secondary aim of the 1953 effort was to treat and cap as many walls of rooms in the central room block of the North Wing as possible with available funds. However, since the earlier soil-cement stabilization of the South Wing was not as enduring as anticipated, it was necessary to redo some of those rooms. Being constructed of irregular cobbles, the walls of the South Wing were particularly insecure. [114]

One task completed in 1954 was the reroofing of the Great Kiva for the second time in its 20-year history.

A second job for 1954 was the stabilization of the Hubbard Mound after its excavation. Since the site was just a few feet from an irrigated orchard, with a central kiva and room foundations below the farm land, there was the likelihood of insurmountable preservation problems. Several generations of aboriginal builders created a communal house of poor grade sandstone set up in copious amounts of even softer mud mortar. A thick finish coat of mud plaster covered all surfaces. Stabilizers were faced with especially difficult preservation. They reset and capped facings and the top one or two courses of sandstone block masonry using tinted cement mortar. They replaced many decayed stones along wall tops and bases and rebuilt expanses of eroded mud wall cores to which some original plaster still adhered. Prior to its inclusion in the monument, owners of the site broke into and cleared out several of the Anasazi rooms, reroofed them with planks, set doors in openings made in the walls, and used them for root cellars. The stabilizers removed the modern roofs and doors and filled the holes in the walls. [115]

1956-1969

National Park Service experts judged 20 years of concerted stabilization at Aztec Ruins National Monument to have been sufficient at last to place the structures in such a state of repair that future work could be devoted to routine care. This was what was called "maintenance status." Also, by that time the Mobile Unit was renamed the Ruins Stabilization Unit, with headquarters in the recently formed Southwest Archeological Center in Globe, Arizona. Gordon Vivian remained its director.

During the summer of 1956, a Ruins Stabilization Unit crew, supervised by Vivian and directed in the field by Richert, corrected problems on walls of nine rooms and Kiva E and sealed leaks in concrete slab roofs over four rooms and the shed roof above Room 117. Stone masons used tinted cement mortar, sometimes concealed on wall faces by mud grouting. Other accomplishments in the West Ruin in 1956 included modifying the surface drainage north of the ruin so that water flowing on to the monument from adjoining private lands was diverted by earthen dikes to the southeast and out of the area. The drainage line laid in 1946 along the north boundary was cleared and repaired. A dry well was sunk at the northwest monument corner, and various drain systems within the ruin proper were reconstructed. It was at this time that a burial found in a nearby field was placed as an exhibit in Room 141. [116]

Richert also spent several weeks during the summer of 1956 making repairs to the East Ruin, where previous preservation dealt with rooms with original ceilings. This time the crew worked in seven excavated or partly excavated roofless rooms, most of which were dug by Morris in the 1920s. Convinced that Earl Morris's interpretation of the East Ruin as a Mesa Verdian construction was correct, Richert is thought to have modeled his repairs after the style of masonry used in that area. The men replaced or reset loose cobbles and capped tops of some walls. In both instances, they used colored cement mortar. Because of their poor condition, it was necessary later to backfill Rooms 15, 16, and 17. [117]

At the end of the field work in 1956, it was time to take stock once again of what had been accomplished and what remained to be done in the foreseeable future. The principal problem in the East Ruin was the large amount of heavy debris over aboriginal roofs causing beams to split. In the West Ruin, the continual stoppage of the deep north drainage line, promoting periodic flooding of the northern tier of rooms, was listed as a high priority problem. With self-guided viewing a possibility, stabilizers were concerned that tops of walls did not become walkways. Comprehensive stabilization of the Hubbard Mound was considered complete. [118]

Attention to the East Ruin was renewed during the summer of 1957, when Richert placed shielding roofs over seven more rooms having intact prehistoric ceilings. That put 11 such superstructures in the East Ruin, with four ceilings still lacking protective cover. Workers scraped away mounded wall rubble and dirt, nine feet in places, before roofs of reinforced concrete covered with pitch and obscured by dirt were secured in place. As usual, workers capped and repointed standing walls of rooms cleared for repair with tinted cement mortar. They carefully removed the fill that accumulated within the open chambers, varying in depth from 15 inches to five feet eight inches, so that room walls could be worked. They replaced beam supports in some cleared rooms by steel cradle braces suspended from the new concrete roofs. [119]

Maintenance stabilization was resumed in the West Ruin on a large scale during the fall of 1959 and the summer of 1960 by Joel L. Shiner, supervised by Richert. Shiner's crew consisted of eight Navajo Indians. During the first phase of this major effort, the Indians worked over 14 rooms, four kivas, and parts of the northern sector of the courtyard. In 1960, they attended to another 51 rooms, nine kivas, and other parts of the courtyard. During these campaigns, masons used tinted cement mortar, frequently pointed over with local mud, to recap certain walls and reset sandstone blocks in kiva and wall veneers and basal courses. Laborers replaced some wooden lintels over doorways and ventilator openings. Using waterproofed concrete, the men poured foundations under a few walls and took down and rebuilt sections of walls whose veneers separated from cores and expanded outward. They dug dry wells to improve interior room drainage. They made repairs to wood-and-tar paper roofs over concrete slab coverings of seven rooms. [120]

Because the modern shed roof covering Room 117, which contained some designs scratched in the plaster, was damaged by seepage from higher construction in the North Wing, laborers dug along the exterior of the north room wall. They plastered the wall surface with a cement and Hydropel mixture. When dry, they then coated that surface with tar before they graded the ground around to drain away from the room. [121]

In the on-going search for a mortar that would approximate Anasazi mud in appearance but be more long lasting, by 1960 Vivian decided that bitumens and soil-cement were unsatisfactory. Consequently, Shiner and a Navajo crew set about reworking walls in the Hubbard Mound. They stripped the failing soil-cement off stone block and cobblestone walls and recapped them with unadulterated tinted cement. They reset missing and decaying stones with the same building material. After nailing poultry wire to wall surfaces, they spread tinted cement plaster over them. They elected to leave stones protruding through the plaster to emphasize the fact that the walls were built primarily of stone. The finished product was ugly and failed to resemble the work of the Anasazi. [122]

For three months during the summer and fall of 1961, Shiner returned with a Ruins Stabilization Unit crew varying from five to 14 Navajos. One more time, they recapped and repointed walls of the North and West wings of the West Ruin. In all, they treated 38 rooms and one kiva. [123]

Cracks developing in the walls of the Great Kiva prompted a professional examination of its foundation in relation to the conditions of water table, precipitation, and irrigation. Hydrological experts drilled five test holes near the structure. The holes went down to 5,617 feet above mean sea level, or what was presumed to have been the surface at the time of construction. Next, the team bored 24 hand auger test holes in and around the exterior of the Great Kiva. The consultants concluded that natural precipitation and poor roof drainage were more to blame for moisture and cracking within this particular building than was irrigation seepage. Unless function of the kiva changed, the experts considered the building to be safe, although standing water was observed at nine feet below the surface. [124]

Upon an inspection in 1962 of the deep north drain line, Richert discovered that, apparently without knowledge of its existence, workers at some time graded the land on the north side of the West Ruin and buried at least three manholes. They could not be located or opened for examination. The line was perennially plugged, and the outfall was silted up and overgrown with dense brush. Overflow of the Hubbard pond was creating an adjacent bog and threatening the East Ruin. Remedial action by the Ruins Stabilization Unit group was carried out the following year. [126]

A 10-man Navajo Ruins Stabilization Unit crew, led in the field during the summer of 1965 by Charles B. Voll and Martin T. Mayer, continued replacing bitumen mortar with colored cement. Part of the group reworked 22 rooms and three kivas of the West Ruin. Another group repaired roofs and treated all exposed prehistoric wood in 16 ceilinged chambers with a wood preservative. In the West Ruin, masons regrouted the walls of 19 rooms with colored cement. They treated six rooms and one kiva of the Hubbard Mound in a similar manner.

A stabilization inventory prepared in 1965 stated that further repair work at Aztec Ruins could be done at five-year intervals. This should be accompanied by frequent preventive measures, such as cleaning out the metal trough drains over protective roofs, the sump located outside North Wing Room 193 that collected drainage from the four north-south chambers through which the visitors' path led into the courtyard, and the tile room drains. Weeds and brush that could interrupt the drainage should be kept at a minimum. The north side drain should be flushed out with water under pressure at least once a year.

Following an unusually heavy series of rains during the spring of 1967, which caused parts of both ruins to give way abruptly, the Ruins Stabilization Unit again was called to the rescue. Mayer and five Navajos spent a week in September undoing the wreckage. They administered stabilization first aid to cobblestone walls of two rooms in the East Ruin and similar walls of almost all rooms of the South Wing of the West Ruin. [127]

Sanders Construction Company, of Farmington, was awarded a contract in February 1968 totalling $11,371.50 to redo two roof drains at the Great Kiva and install new pipe, concrete drop inlets, and associated earthworks in the courtyard. [128]

1970-1980

It was apparent by 1970 that, despite frequent stabilization work at Aztec by dozens of the most experienced men in the business and the investment of large sums of money, the condition of the ruins was becoming worse. What initially were mere vestiges of a long-departed civilization were being further devastated. The Resources Management Plan of 1973 proposed a five-year major overhaul followed by annual preventive stabilization. [129] Additional intensive stabilization and refurbishment of earlier repair attempts were in order. These measures were to include chemical waterproofing of floors, fill, and wall bases, and chemical preservation of the masonry stone. The usual wall capping, resetting of loose stones, work on the drainage, and bracing of weakened roof beams should continue. An emergency appropriation for badly needed multiyear endeavors was solicited from the Regional Office.

Funds were made available for a three-to-four-year special preservation project. The severity of the problems so intensified as work progressed that it took six seasons and additional money to bring the Aztec Ruins to an acceptable state. Beginning in June 1973 and continuing for three or more months each summer through 1978, trained crews of five to a dozen workers, most of whom were Navajos, applied their expertise to Aztec Ruins. The first three seasons, George Chambers of the Ruins Stabilization Unit then headquartered at the Arizona Archeological Center in Tucson planned the work. Each season different trainees in ruins preservation techniques oversaw the field program. These were Peter Laudeman in 1973, Marianne Trussell in 1974, and Stephen Adams in 1975.

The team in 1973 rehabilitated 47 rooms and three kivas, principally in the West Ruin, using tinted cement and soil-cement mortars. Apparently soil-cement had returned to good standing. The workers repaired basal erosion of walls, recapped degenerate wall tops, and regrouted and replaced loose or missing stones in wall veneers. They spent a lot of time reworking Kiva N of the West Ruin and Kiva 2 in the Hubbard Mound, where hard rains during the previous winter caused considerable havoc. They replaced tile drains, whose outlets were flush with the exterior of the north wall of the West Ruin, by metal drains extending far enough beyond the wall to carry water away from its vertical face and beyond its foundation. [130]