|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 10: THE MISSION OF MISSION 66

On a tide of peace, prosperity, and renewed national vigor that characterized the mid-1950s, planners for the National Park Service implemented a bold effort to upgrade all aspects of the facilities at the 179 holdings it maintained at that time. That meant modernizing or constructing new buildings to accommodate increased public usage and to provide for necessary augmented staffing, to build or improve roads and trails for easier or greater accessibility, to push stabilization measures where needed, to bring written, oral, and visual interpretation in line with current research, and to expand each installation's offerings for greater visitor enjoyment. [1] Aztec Ruins National Monument was slated to receive the benefits of this 10-year program, known as MISSION 66 in recognition of the Service's upcoming 50th anniversary in 1966. It was none too soon. Both physical and presentation capabilities of the monument were inadequate and outmoded.

At the root of the problems faced at Aztec Ruins was the fact that the 1950s witnessed a remarkable popularity of the subject of archeology. Recent global wars perhaps stimulated interest in the world's cultural past. In the Four Corners, it was rather ironic that explorations to satisfy the twentieth century's dramatic energy needs focused unusual attention upon the human pageant played out there the previous millennium. A cobweb of jeep trails lay over sweeps of inhospitable terrain scarcely penetrated by Euro-Americans for the preceding 100 years. Along with the discoveries of coal, natural gas, oil, and uranium were those of the remains of scores of Anasazi sites. Nomadic Native Americans, who wandered through the area since the 1400s, superstitiously generally avoided these homes of the ancient people. Not being restrained by the same fears, Caucasian Americans pothunted as never before. This was redeemed somewhat by their new awareness of the civilization that once evolved in, and then departed from, this unforgiving wilderness. In an oblique way, this was reflected in the filming within the precincts of Aztec Ruins of part of the James Cagney movie Run for Cover. [2]

Boom conditions in the San Juan Basin resulting from energy developments brought changes affecting Aztec Ruins. One was a rapid tripling of local population. Another was a system of paved highways ending the regions' isolation (see Figure 6.1). Tourists by the thousands took to their automobiles to find that, although Aztec Ruins was not in the spectacular setting of Mesa Verde or Chaco Canyon, it could be enjoyed during a brief side trip while en route to somewhere else. School field trips to easily reached places of interest became a standard part of the curriculum. All these factors coming together -- interest, numbers of adults and children, and accessibility -- accounted for an annual visitation at the monument that burgeoned to almost 40,000 by 1956 and was expected to increase further as the local natural gas and oil activities expanded. [3]

The ways in which the National Park Service made the monument available to visitors involved a number of coordinated facets to the operation. The most urgent of these were targets for improvement under the MISSION 66 umbrella.

National Park Service monument and park headquarters transformed into visitor centers in accord with the underlying mission of MISSION 66 to emphasize users rather than managers. The visitor center at Aztec Ruins National Monument was designed to serve two interrelated spheres of the monument's purpose.

FOR USERS

The Fourth Museum

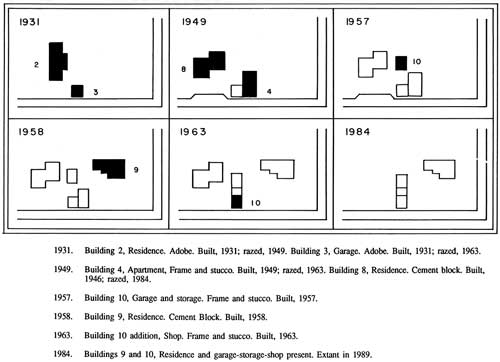

An informative, attractive museum was a vital cog in the educational machinery which MISSION 66 wished to stress. Ideally it was where the goods of daily life demonstrated Anasazi adaptation to this particular setting and to each other. The great house behind the modern buildings was a mere backdrop, sterile in its excavated state except for the obvious building expertise and muscle power of Anasazi workers. The existing Aztec Ruins museum, however, did not come up to standards of the 1950s. From its beginning 20 years earlier, it was regarded as a temporary display of specimens. A drawing prepared in 1950 suggested an arrangement reclaiming the north end of the main museum room as a work area. This loss of space would be compensated for by a new extension southward. The actual square footage of exhibition space would not increase. [4] This remodeling was not done. Six years later the MISSION 66 prospectus prepared by Superintendent Homer Hastings stipulated that a first program for the monument must be either the rehabilitation of the existing museum, provisions for additional exhibit space, or both. [5] The prospectus, including an estimated $136,000 for new construction to incorporate a museum, was approved in 1957 by Robert M. Coates, acting chief of MISSION 66. [6] Finally, during the tenure of Albert H. Henson, the fourth, and only adequate, Aztec Ruins museum became a reality (see Figure 10.1). More than 40 years passed since Henry Abrams expressed his dream of just such a depository.

|

|

Figure 10.1. Evolution of Visitor Center. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

On May 21, 1958, an invitation for bids on a new museum wing to the administration building at Aztec Ruins National Monument was issued by the Western Office, Division of Design and Construction, in San Francisco. [7] Seven months later the Farmington Daily Times announced that the construction was completed. It was designed by Charles Sigler and overseen by Ray T. Olsen, both of the Western Office, Division of Design and Construction, and executed by Goodman and Sons, contractors of Farmington. The cost was $72,631.90 (see Table 10.1), a phenomenal sum when considering that the museum proposed 20 years earlier overshot the $9,000 limit of the total administration-museum building and was eliminated.

|

Table 10.1. MISSION 66 Expenditures Public Projects | |

| Museum Visitor Center Trails, 0.7 miles Wayside Exhibit |

$ 72,631.90 74,508.77 5,908.42 332.23 |

|

Utilitarian Projects | |

| Residence #9 Utility Building Parking area Sewer System Irrigation System Fence Walls, well house, gate 2 fire hose houses Lawns |

$ 24,951.34 7,615.91 3,000.00 13,182.83 3,333.59 2,293.34 3,684.42 1,532.71 418.00 |

|

aAztec Ruins National Monument, MISSION 66 Accomplishments; Superintendent to Regional Director, National Park Service, July 1, 1956; July 16, 1963; August 20, 1963 (Document file, Aztec Ruins National Monument Headquarters, Aztec, New Mexico). | |

Although the first plans for this fourth Aztec Ruins museum called for a square room to be added to the northeast corner of the administration building, it emerged finally as a squared-U room of approximately 1,200 square feet wrapped around the east end of the masonry-walled lobby built in the 1930s. A southern projection extended at the east end of the entrance porch and a northern projection matched it at the opposing end of the rear porch. [8] The northern room housed a new furnace to replace the obsolete heating apparatus in the basement. Constantly rising costs ruled out the sort of imitation of Anasazi architectural details as had enhanced the first lobby.

The lobby, formerly used for orientation, became a place where visitors could sit to enjoy Admatic projected scenes related to the Anasazi experience or their colorful Four Corners homeland. Several wall bays still held stationary exhibits. One of these was a cross section of a hypothetical deposit to show how trash layers accumulated. This exhibit was put in place after 1935.

Exhibits and Collections

The new museum exhibit plan worked out in 1957 by Museum Specialist Myron Sutton was approved by the regional chief of interpretation and the monument superintendent. [9] It drew heavily on recycled materials from the museum of 1937; in fact, displays simply were shifted from one room to another. [10] In the new, spacious, well-lighted location, they appeared shabby and old-fashioned. They relied too much on drawings, printed matter, and cluttered charts. The 20 intervening years between the third and fourth Aztec museums witnessed great changes in museum techniques in general and interpretations of Southwestern prehistory in particular.

Within several years after its installation, so much dissatisfaction was expressed about the supposedly updated Aztec Ruins museum that Museum Specialists Leland Abel, Western Museum Laboratory, and Franklin Smith, from the regional office, made a trip to Aztec to review the exhibits case by case. They agreed that only two of the 26 exhibits could be reused without alteration. For the others, they recommended corrections of labels, rewriting of texts, or complete redesigning of contents to make them current scientifically. [11] The corrected archeological map of the site replaced the Morris map of 1924. [12] Duplications of similar exhibits in other Southwestern monuments were eliminated. These included dendrochronological and archeological methods, the unique topography of the Four Corners, modern Northern Pueblos (who might be descendants of some of these Anasazi), and early life of a pueblo dweller.

The over-all emphasis of the revamped museum was on sparse but succinct wording, relatively few but diagnostic objects, and art work conveying meaning but also attracting attention. Retained were modified cases devoted to architecture, agriculture, hunting and gathering, healing and curing, weaving, pottery making, trade, and religion. Material in several cases outlined the discovery of the area by Euro-Americans and the site's excavation by Morris. An exhibit on food preparation contained a sketch of roasting pits similar to ones found the previous summer during stabilization of Rooms 51 and 52 in the East Wing. [13] Sixteen wall exhibits and three free-standing exhibits made up the presentation in new cases to which the Farmington Construction Company applied furring strips at a cost of $1,990. [14] The various changes were not completed until the end of 1965. [15]

One special object shown in a case prepared at this time was a coiled basketry plaque 36-by-31 inches. It was decorated at its outer edge with minute flecks of selenite and coils stained red and green. Morris called it a shield when he found it in a grave in 1921. Although a hard wooden handle attached to its under side made it an object that could be held erect in front of the body, whether it was a shield is uncertain. Regardless of function, it was a rare specimen whose fragile condition required expert preservation attention. This was particularly true if it were to be shown in a vertical position. The specimen was sent to the Archeological Preservation Laboratory at Globe in 1956 to undergo treatment. [16] Fearing that it would fall apart under museum conditions, curators there proposed that a display replica be commissioned from either a Hopi or Pima craftswoman. The original specimen should be kept in controlled storage. [17] That course of action proved to be an impossibility. Either modern Indian women did not want to copy an aboriginal object due to superstitions about it, or they could not imitate old basket making techniques. [18] In the end, the so-called shield was shipped to the Western Museum Laboratory, where it was rehabilitated, mounted, and returned to the monument in February 1964. [19]

Included in the Aztec Ruins museum case with the shield were Mesa Verde Black-on-White pottery vessels, bone awls, a hafted stone knife, and ornaments found associated with the remains of an adult male. Morris thought of him as a warrior because of the presumed shield. The actual skeleton of this individual was omitted from the exhibit.

Collections available for exhibition in the new museum at Aztec Ruins had not changed appreciably during the years between the first and fourth museums. Approximately 300 items were acquired because of excavations necessitated by stabilization or expansion of the interpretive program. [20] However, the basic resources remained materials loaned to, but not owned by, the government.

Two private collections received notable attention during the interim period between museums. One was that of Sherman Howe. In 1940, he withdrew approximately a third of his personal artifact collection, but in 1953, at the age of 83 he gave the balance to the Aztec Ruins museum. A small ceremony in the lobby featured his signing the necessary papers to make the transfer legal (see Figure 10.2). [21]

|

| Figure 10.2. Sherman S. Howe, lifelong friend of Aztec Ruins. Photograph taken in 1949 at age of 83 years. |

A second withdrawal occurred in 1954-55 when Rosa Abrams, angered about transfer away from the monument of her family donations housed at the site since 1928, asked to have most of the specimens in the Abrams collection returned. The Abrams family was assured originally and as recently as the late 1930s that the entire assortment would be kept forever on exhibit. [22] Given the changing physical circumstances of the installation, this was a condition to which it was impossible for the museum to adhere. Furthermore, the acceleration of regional archeology robbed most of the specimens of their uniqueness. In 1954, Homer Hastings, who had returned to Aztec Ruins National Monument the previous year to be superintendent, tabulated 163 artifacts or groups of artifacts as donated by the Abrams family. Of that number, 70 were then on exhibit, 19 missing items were presumed to have disappeared from the earlier open displays in the ruin, and the remaining were moved for storage elsewhere. [23] A list of 1955 indicates that at that time 160 specimens were returned to Mrs. Abrams. Hastings acknowledged another 38 articles given by her to the National Park Service, of which 20 were kept. The remainder were so fragmentary or decayed as to be worthless. [24] The two listed assortments do not tally to 163 but probably diverge slightly because of numbers assigned to bulk entries or to fragments.

The Abrams misunderstanding resulted from movement of specimens from Aztec to the National Park Service's newly acquired facilities at Gila Pueblo in Globe, Arizona. This transfer began in 1953 and continued intermittently over the next 12 years. [25] Ultimately, between 1,700 and 1,800 artifacts of a total of 3,555 to more than 4,200 items were moved to the Southwest Archeological Center. [26]

The removal of artifacts from Aztec Ruins was necessitated by unacceptable storage conditions in the 576-square-foot basement of the house built by Morris in 1920. During his active years at the site, Morris stacked duplicate specimens, those too weighty or cumbersome to ship to New York, or other things needed for preparation of reports in cardboard boxes or put them on wooden shelves around the walls. After the house was given to the government, the American Museum requested permission to leave the artifacts stored there so long as Morris continued to hold a lease on it. [27] When Morris vacated the house in 1933, the collection was left in the basement under care of the monument custodian. In the course of the construction begun at that same time, much shifting of these materials occurred when sacks of cement were piled in what had been the cistern at a lower level and when a new furnace was installed in the basement itself. Predictably, some labels were lost, paper bags broke, contents of boxes were shuffled, there was not enough manpower to keep order, and there was no other adequate space available for what was then the largest artifact collection at any Southwestern monument.

Storage conditions did not improve during the next 20 years. As part of MISSION 66, the antique furnace was abandoned but not removed. [28] It, and a cement pillar supporting the lobby fireplace, continued to occupy most of the central floor. Steel shelving was provided for the remaining basement storage, and plastic sheeting kept some specimens dust-free. Because of lack of space, humid conditions or seepage, poor illumination, insects, rodents, the tendency to use the basement for extraneous goods, no physical security, and no curatorial help, arrangements remained unsatisfactory.

The principal collection upon which museum technicians could draw for the Aztec Ruins museum of 1958 was that which belonged to the American Museum of Natural History. National Park Service personnel mistakenly assumed it was given to the government, along with the various tracts of land, or was left at Aztec Ruins on permanent loan. Contributing to the clouded question of ownership was Morris's failure to keep complete records of specimens going to New York and those being kept at Aztec and the intermittent, inconsistent cataloging by National Park Service staff. One session of curation, carried out by Janet Case, was part of the 1934-35 Public Works Administration activities. Miss Case had no previous association with Aztec Ruins and may have made mistakes in attribution. Later, when war was imminent in 1941, an itemization listed 238 objects believed irreplaceable or unusually valuable as gifts from the American Museum. There is no verification of such transfers. [29] Another collection from the early excavations, comparable in size to that at the monument but considered superior in quality, was in New York. [30] In the meantime, some American Museum specimens had been or were being moved from Aztec Ruins to the Southwest Archeological Center. A second cataloging session at the monument came in 1957, when John Turney, then archeologist attached to the Southwest Archeological Center, brought accounts up-to-date in preparation for the new Aztec Ruins museum.

No articles exhibited in the new museum were borrowed directly from resources at the American Museum. Eventually 81 American Museum objects still at the monument or in Globe were incorporated into displays, where they have been for the past 30 years. Ten items included in exhibits in the new museum were part of the Howe gift. Three relatively insignificant Abrams artifacts -- a yucca pot rest, a piece of reed matting, and a sherd of trade pottery -- also were used. The remainder of displayed artifacts came from repair work or small individual donations.

The use of some artifacts from sites other than those in the monument is flawed presentation. Moreover, the available collections as a unit do not represent well the earlier phase of occupation present on the site. The major strength of the collections lies in the unusual range of perishables from the classic Pueblo III period.

Research

Research to increase viewer understanding of the prehistoric story laid bare at Aztec Ruins was one of the MISSION 66 goals. Planners considered several excavation possibilities and decided each was impractical at the time. One was the East Ruin. The scientific reasons for excavation of this site centered on settling questions of Chaco versus Mesa Verde occupations using field and laboratory techniques far advanced over those employed by the pioneering American Museum team of one. However, funding for the enormous and complex undertaking was not available. A second possible target for excavation was the courtyard of the West Ruin in order to determine the extent of its utilization before erection of the Chacoan great house. Work there had the drawbacks of inconvenience for both diggers and visitors and, because of severe drainage problems, of unfavorably tipping the delicate balance between ruin survival and its destruction. At the time, stabilization difficulties were at their most critical level.

Superintendent Hastings presented a number of other research topics, which he felt would enhance the Aztec Ruins story. These were a restudy of the two ceramic traditions represented at the West Ruin, analysis of the relationship of Chaco and Mesa Verde branches of the Anasazi, an archeological survey of surrounding areas, compilation of a trait list, and a collection and study of vertebrates and insects native to the locality. [31] The Master Plan of 1964 for Aztec Ruins National Monument and a contemporary Southwest Archeological Center report specified some of these same topics as worthy of consideration. The Southwest Archeological Center paper stressed the need for sampling horizons prior to the twelfth century. [32] None of these proposals was carried out.

Nonetheless, several lesser pieces of research were finished during the MISSION 66 period. One resulted from clearing the grounds in front of the visitor center so that they could be landscaped. What was suspected of being a prehistoric trash heap was located to the northeast of the parking lot (see Figure 3.22). [33] Archeologists James C. Maxon and George Chambers confirmed that the four-foot-high undisturbed mound was an aboriginal dump. Rodents cached intrusive peach and apricot pits in it. [34] The old refuse probably was left from the terminal occupation of the West Wing rooms just to its north, where Mesa Verde tenancy was most intense. [35] Even so, there were some signs of a Chacoan deposit at the mound's eastern side. That correlates with Morris's description of a southwest Chacoan refuse deposit. [36]

A study done by Lyndon L. Hargrave, long-time student of the Anasazi and then a collaborator in ornithology and archeology at the Southwest Archeological Center, concluded with the identification of species of birds represented in bodily remains and artifacts uncovered during stabilization. Identifiable species probably used for food and feathers were Canada goose, red-tailed hawk, golden eagle, grouse, mourning dove, black-billed magpie, and common raven. All these types of birds are modern residents in the area. The overwhelming source for bird bone needed for objects such as awls and bead tubes was the sole species of turkey native to North America, the Meleagris gallopavo. [37] The great economic importance of the turkey was demonstrated further by a microscopic examination of feather materials on more than a 100 Aztec Ruins items at the Southwest Archeological Center in 1960. Articles with feather filaments, down, or barbs were socks, robes, bags, rope strands, and arrowshafts. Without exception, all these feather remains were Meleagris gallopavo. [38] Hargrave pointed out that leg or foot wear, actually socks that extended up a wearer's leg about six inches, were made of netted yucca cordage. Only under a microscope could he see tiny pieces of quill and feathers inserted into the meshes to provide warmth and comfort. [39]

The evidence for bird types examined by Hargrave does not represent the complete gamut present at Aztec Ruins. Of more exotic importance were macaws from Mexico. Their recovered remains are in the American Museum collections in New York.

Interpretation and a Self-Guiding System

Up to the 1950s, all visitors to the monument were conducted through the ruin and the museum by the custodian or park ranger, who, as the party moved along, informally explained features of the site and of Anasazi life as they comprehended them. Groups were limited to about 20 persons. The small size of inner chambers of the ruin and that of the museum made it difficult for the leader to project his remarks to those standing at a little distance. Also, designers meant narrow trails for single-file walking. When there were only two men on duty, one remained at the registration desk to collect required 25¢ fees. While stationed there, he introduced those waiting for the next tour to the history and natural surroundings of the monument as they were outlined in nearby displays.

The success or weakness of personal interaction between the National Park Service personnel and the public depended to a large degree upon the personalities of the guides and their abilities to convey knowledge in an interesting and accurate manner. What they said and how they did it inevitably molded the visitor's conception of the cultural story that unfolded at Aztec Ruins.

Just prior to MISSION 66, a small group of archeologists attached to the regional office in Santa Fe and to the Southwest Archeological Center at Globe were tangled in an imbroglio threatening to contradict the official National Park Service reconstructed history of Aztec Ruins. Erik K. Reed, Harvard educated regional archeologist responsible for interpretation, was convinced through his field work in Mancos Canyon during the 1940s that Morris was incorrect in his proposed sequence of occupation of the West Ruin. In Reed's opinion, there was a continuous, rather than interrupted, occupation of the village and of the general San Juan Basin. Complexes of "Chacoan" and "Mesa Verdian" attributes merely represented temporal phases of a long steady continuum of cultural evolution, not actual successive disruptive movements of people. He expounded upon this theory at a gathering of regional archeologists in the summer of 1953. To substantiate his beliefs, he stated erroneously that excavations then going on at Hubbard Mound failed to expose a sterile stratum demonstrating a break in site utilization. [40] Within a month, his theory became fact for Reed. He issued a dogmatic memorandum ordering Aztec men in the field to cease repeating a story that was "unacceptable" and to replace it with the "true situation." [41]

Upon receiving a copy of this memorandum, Morris responded with a long defense of his interpretation. He cited evidence from Rooms 43, 145, 149, 155, 174, and 189 of clear differentiation between lower Chaco and upper Mesa Verde deposits separated by various floors (see Figure 3.14) and the lack of mixed trash deposits such as one might expect had there been no interruption in utilization of them. "It would be difficult to convince me that there was not an hiatus between the Chaco and Mesa Verde phases," he wrote. [42]

Most National Park Service regional scientists joined in taking exception to what seemed to be Reed's untenable theory and to the ultimatum tone of his instructions to the men working at Aztec Ruins. The passage of time and stepped-up tempo of research warranted a reexamination of old ideas, but Morris's early day efforts were sound. They should remain unchallenged in the absence of any additional National Park Service excavation in the West Ruin, other than the limited Steen work in 1938. Everyone accepted the fact that in the San Juan Basin there had been interaction and overlapping of divergent strains of Anasazi development. To what extent remained a question for future researchers. For the present, the National Park Service archeologists recommended that guides at Aztec Ruins and distributed literature note that further work might lead to alternative explanations of what had transpired at this particular community. Reed withdrew his insistence upon a change in the Aztec Ruins presentation.

Within a few years, the National Park Service adopted a theme for Aztec of the dynamics of the cultural contact between Chacoans and Mesa Verdians, functioning because of the site's intermediate geographical location between the two focal areas and the continuity through time of the fundamental cultural content. This was demonstrated through pottery, architecture, trade, and possibly also through intermarriage and sociological intrusions. [43]

In the early 1950s, greater visitation and financial stringencies forced a change in procedure for introducing visitors to the monument. Because a self-guiding approach had been tried successfully in other Southwestern monuments, in September 1954, this practice was put into effect experimentally at Aztec Ruins. [44] Following a model written by Ranger Robert Hart in 1935, a booklet was prepared to give to each visitor explaining things to be observed at designated stops along a trail. [45] Judged effective, the next season self-guided trips were adopted routinely. With advance arrangements, large parties could request a tour guide. In months of greatest visitation, one or more rangers were on duty in the ruin to answer questions and to provide fuller background than what was presented in the brief printed matter.

A number of information aids made tours more enjoyable. Trailside exhibits and free-standing easels contained additional information. [46] Plate glass sealed into southern openings along the corridor of rooms with ceilings allowed a view of uncleared portions of the site or a piece of reed matting in situ over a doorway. Message-repeating equipment in the Great Kiva provided music such as once reverberated through the hall.

Over the years, other interpretive improvements were made. The trail route occasionally was changed for better or safer circulation or to provide opportunity to see other features. Visitors were not encouraged to walk into the inner East Wing from the court trail, but neither were they barred from doing so. Because getting there meant climbing on walls, most of the northwest corner of the house block was off limits. A new trail was cleared to the Hubbard Mound. As it became apparent that funds to undertake additional excavations along the route would not be budgeted, a more-encompassing path planned around the perimeter of the monument eventually was abandoned. Superintendent Jack R. Williams recommended that it not be built. [47] Trail guide booklets, keyed to 21 numbered stakes that later replaced trailside exhibits, underwent a half dozen revisions, some with colored photographs and some for sale. Committing the Aztec Ruins history to paper emphasized the need for interpretive guidelines so that all parties concerned spoke with one voice. In 1963, John M. Corbett, chief archeologist for the National Park Service, prepared a comprehensive handbook. [48]

At first, the monument staff expressed apprehensions about allowing unaccompanied persons in the ruins. They wondered if the absence of personal contact with a ranger would reduce the value of the visit to those with no background in regional prehistory. They learned, on the contrary, that many people welcomed the chance to roam at will about the tumbled-down settlement, lost in their own thoughts. Would there be careless vandalism or personal accidents? Since ceiling beams generally were out of easy reach for those with an urge to carve initials and delicate patches of engraved or painted plaster were protected with screens, the threat of that kind of vandalism was reduced. Visitors might be tempted to get on to unstable walls. To discourage that, tops of such walls were lined with loose building stones. To insure personal safety, the precarious steps down to the Great Kiva floor from the ground level were replaced by a sturdier wooden staircase with hand rails. [49] Trails were rerouted, leveled, and surfaced. The incidents of harm to the ruin either because of legitimate visitors or trespassers who came after regulation hours proved negligible. Few injuries were reported.

FOR MANAGERS

Work Space and Utilities

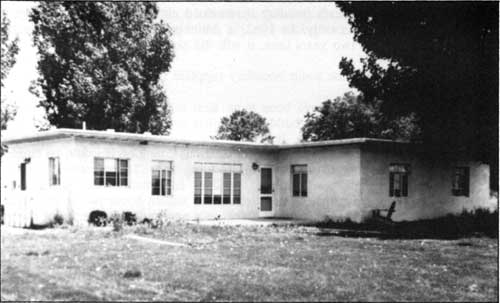

A MISSION 66 project once again remodeled the old American Museum field station to provide more breathing space for the daily administrative business of the monument. [50] Doubtless, Morris would have been amused at the cyclic changes imposed on his structure, and doubtless, he would have been pleased to see a memorial plaque dedicated to him in July 1957 placed in a prominent place there. [51] Walls were rearranged to create a reception and information area with a sales counter in the two front rooms of the original house. Offices were made out of the rear rooms and the former museum. West windows and the south T-shaped doorway of the west room were reopened after having been sealed during the 1935-1958 museum interlude. The rear, or north, T-shaped doorway through which tours entered the museum gave access into a new work room added to the northwest corner. This room opened to a covered porch across the rear of the building. Two rest rooms and a plumbing alley were put on the southwest front corner, from where they were connected to Aztec city water and sewer lines (see Figures 10.1 and 10.3). [52]

|

| Figure 10.3. Visitor Center, Aztec Ruins National Monument, 1959. Museum addition at right center; rest rooms at left center. Original American Museum field station, or Morris house, is at center rear left; lobby constructed in 1934 is at center rear right. |

During the World War II years, adjudication proceedings were undertaken in order to ascertain rights held by stockholders in the Farmers Ditch Company. The nine original holders in 1892 had increased to 57 by 1944. Since the amount of his irrigated land transferred to the American Museum of Natural History totalled only 1.6 acres, Abrams sold the institution just one-sixteenth of his one-half share. In the 1950s, the water available was piped into 357 feet of 12-inch underground tile running across the Hubbard property from the Farmers Ditch to the northwest corner of the monument. [53] From there, it was diverted to irrigate new landscaping featuring native plants. [54]

Residential/Maintenance Area

The small adobe custodian's house (building 2) erected in 1931 on the southern piece of monument land was subject to the same troubles with underground water that were threatening the ruin (see Chapter 12). When Custodian Miller asked for a supplemental emergency appropriation to attempt correction of drainage within the Anasazi structure, he added:

It might be well to mention here the condition of the custodian's quarters due to underground seepage. We have just finished replacing the floors in the kitchen and hall, which had rotted out due to moisture. Upon removal of the rotten flooring it was found that the concrete sub-floor was for the most part completely rotted out. Upon removing the mop boards it was found that the adobe partition walls were also completely water-soaked. All in all it is a dangerous situation and is certainly a detriment to the health of anyone living under those conditions. [55]

In the 12 years since the house was built, subsurface water had managed to work its way relentlessly downslope beneath the ancient house, beneath the modern house, and quite surely across the pasture land between the monument and the Animas River.

The next year Acting Custodian Russell L. Mahan submitted a proposal for rehabilitation of the house to include waterproofing the sub-floor, laying new hardwood, waterproofing adobe wall footings and replastering. He estimated the cost to be $1,280, or about a third of the original construction cost. [56] It was war time, so action on the plan was postponed.

After the war, a modest construction program revitalized the residential area of the monument (see Figures 10.4 through 10.8). The custodian's house was so dilapidated that it was razed to make way for a 1,400-square-foot cement block structure (building 8) consisting of a living room, dining alcove, kitchen, three bedrooms, two baths, and a utility room. The cost was $16,000. [57] In the same year, a frame-and-stucco addition was placed on the east side of the old garage to serve as an apartment for seasonal employees (building 4). [58] A four-to-eight-foot-high adobe wall with an elevated gate entry opened to the well-traveled county road. The wall provided privacy for what was planned to become a cluster of several houses but posed a visibility hazard on entering or leaving monument grounds.

|

|

Figure 10.4. Aztec Ruins National Monument, boundary status map, 1959. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

|

Figure 10.5. Residence/Maintenance area. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

| Figure 10.6. From right to left, buildings 2, 3, and 4. Photograph taken in 1949 prior to the razing of building 2. |

|

| Figure 10.7. Building 8, 1949. |

|

| Figure 10.8. Building 9, 1958. |

One of the first constructions requested under the MISSION 66 program was a utility building (building 10). [59] It was erected of frame and stucco in 1958 just to the north of the garage and several years later could be reached through a paved utility court off the county road. [60] The dangerous adobe wall along the road was dismantled and replaced by chain link fencing. [61]

In the Master Plan Development Outline written by Superintendent Hastings in 1956, he stated that quarters for National Park Service personnel at Aztec Ruins were adequate. [62] Very shortly, the effects of the nearby natural gas and oil activities changed his mind. Housing became scarce and expensive. Long-term development plans included the addition of two residences for permanent staff and a duplex for seasonals. [63]

The first of the new houses (building 9), a three-bedroom cement block structure, was completed in 1958 at a cost of $24,951.34. It was placed to the east of the utility court (see Figure 10.8). This brought to four the number of service and domestic buildings in the southeastern part of the monument. The house was scarcely done before it was realized that a mistake had been made in the selection of its location. The southward slope of the land and natural drainage channels led directly to the house site. Surveyors established the elevation at the northeast corner of the West Ruin at 5,639.5 feet above sea level. At building 8, it was 5,622 feet above sea level, or a drop of 17 1/2 feet from approximately the north boundary of the monument to the south boundary. [64] The high water table and generally unstable bentonite subsoil added to the problems. Because of little drainage, water to a depth of nine to 18 inches rose beneath floors after rains, walls sweated, and the sewer system backed up. Maintenance workers made repeated attempts to pump water from under the new house, to install dry barrels, and to remove sewage from the septic tank. [65] Finally in August 1961, all the residences were connected to the city sewer at a manhole at the southwest corner of the monument with the aid of a lift station. [66] The ground beneath building 9 remained eternally damp and sticky, and sewage disposal was not corrected satisfactorily. In 1962, a drain put in to the east of the house proved useless. Although it was redone two years later, it still did not work properly. [67]

A natural gas main along the south boundary supplied fuel for the houses. [68]

Government planners should have been more alert to the potential difficulties of using this sector of the monument for contemporary buildings. Similar problems to those at residence 9 had been encountered earlier in the other dwellings. It already was decided by the time of the MISSION 66 work that the seven-year-old apartment was in such precarious condition it would be eliminated. At the custodian's house, despite a very heavy foundation, settling of walls had caused gaping cracks and threw door and window jambs out of plumb. [69] Modern construction was attacked by the same combination of destructive elements that was destroying the ancient house: water and earth movements resulting from it. The Master Plan, 1964, stated, "The soils and underlying strata of the area are such as to create problems of building movement, both prehistoric and National Park Service facilities, as they expand and contract with moisture fluctuation. The residences show displacement of floors and walls. During part of the year, water will stand beneath residence #9 in depths of a foot or more." [70]

Numerous memoranda passed between offices about relocating the proposed residential sites. [71] However, as late as 1963 further housing construction still was scheduled, pending an inspection by the Western Office of Design and Construction. It was cancelled that same year, not by the Western Office of Design and Construction but by the Bureau of the Budget. [72] Meantime, the apartment was torn down. A second utility structure, connected to the first by a breezeway, took its place. [73] The seasonal ranger, who had stayed in the apartment, was moved to a house trailer parked under some trees just to the north. The Master Plan of 1964 concluded that no further housing be considered and that staff secure living accommodations in the adjacent towns.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006