|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 9: SATELLITE ATTRACTIONS

HUBBARD MOUND

Acquisition

Dale S. King, executive secretary of the Southwest Monuments Association, and Erik K. Reed, National Park Service regional archeologist, learned in the fall of 1946 that Clyde C. Hubbard, owner of a portion of the former Abrams property, was planning to hire a steam shovel to remove a large Anasazi mound on his farm. The site was situated just 200 yards north of the northwest corner of the West Ruin block. [1] The mound had been well known during the American Museum project. Part of it then was used by the owner as a root cellar. A northeast room was dug into about 1918 by J.S. Palmer, one of Morris's crew, who found several skeletons and some "degenerate" Mesa Verde pottery. [2] In 1946, the ruin, densely covered with brush, rose above a young peach orchard. Cursory examination convinced King and Reed that it was the remains of a detached Great Kiva. They immediately tried to arrange its acquisition through financial contributions amounting to membership in the Southwest Monuments Association. Ultimately, the Farmington Lions Club and seven private individuals -- including traders Gilbert Maxwell and Dean Kirk and archeologists Harold Gladwin, Marjorie Tichy (Lambert), and Bertha Dutton -- responded sufficiently to meet the $300 asking price for the ruin and a 1.255-acre piece of land upon which it was located. [3] A 20-foot road easement along the monument west boundary was allowed. Its upkeep was Hubbard's responsibility. [4] The Southwest Monuments Association gave the parcel (Tract 5) to the government. It was proclaimed a part of the Aztec Ruins National Monument by President Harry S Truman on May 28, 1948, bringing the total acreage to 27.14 acres (see Figure 5.1). [5]

Excavation and Interpretation

Although from surface indications Morris felt the Hubbard Mound and Mound F between the two great houses likely were related somehow to the Great Kiva tradition of architecture, he thought they differed in having a small center kiva and from two to three rows of encircling rooms. At one time he sunk a pit into Mound F, which hit a burial and Mesa Verde potsherds. A modern storage cellar also intruded upon the Anasazi construction. In his opinion, both structures were remains of Mesa Verde occupation. [6] The structural interpretation ran counter to those of National Park Service personnel, as Reed revealed, and led them to ask for Morris's help. "The ruin is pretty surely a detached Great Kiva, which we should like to see excavated for comparison with the Great Kiva within the main Aztec Ruin, which you excavated and restored. Do you feel that you might be able to do this excavation as a Carnegie Institution project, perhaps in the near future?" [7] Translated, that meant that the National Park Service did not have the funds but needed to know what it was that had been acquired. The Carnegie endeavor did not come about, nor did one to interest Deric O'Bryan, then of Gila Pueblo. [8] Digging by the National Park Service, which followed seven years later, confirmed Morris's reading of the earth.

By 1953, the volume of visitation to Aztec Ruins was of such proportions that it was desirable to open more of the physical remains within the monument to disperse visitors. Almost 22,000 more individuals came to the site that year than came eight years earlier. [9] With such an objective, Thomas B. Onstott, from the regional office, spent June and most of July 1953 initiating excavation of the Hubbard Mound. During the fall, Onstott was followed by R. Gordon Vivian and Tom Mathews, whose assignment was to prepare the site for inclusion in the monument's interpretive program.

Born and raised in New Mexico, Gordon Vivian was one of a growing number of local men and women who, during the late 1920s, aspired to careers in regional archeology under the tutelage of Edgar L. Hewett, then chairman of the new Department of Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. He cut his scientific eye teeth in Chaco Canyon and later was destined to spend several decades there in excavation and ruins stabilization. It was the latter in which he developed such a high level of practical competence that he deserved to be known as the father of this subsidiary field to dirt archeology. However, in 1953 he was given the opportunity to do what he most enjoyed -- dig and interpret what he found.

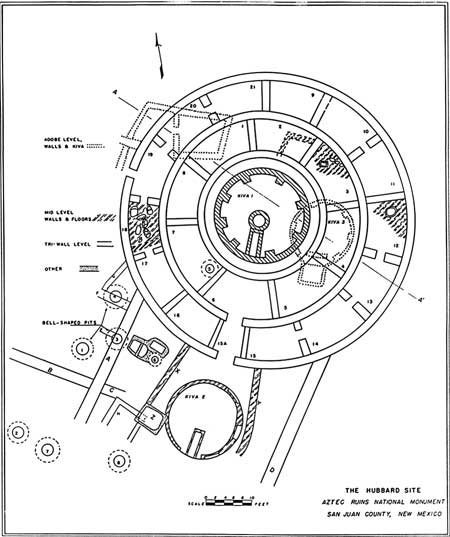

Hubbard Mound was formed by four distinct occupational levels piled on top of each other (see Figure 9.1). [10] The earliest stratum contained some adobe rooms and a kiva built on a gravel alluvial fan deposited by runoff from the cliffs bordering the valley bottom. The monument west boundary cuts across this level, now putting unexcavated parts of the first village under a dirt road leading to the Hubbard house. At some undetermined later period, a second series of rooms and a kiva were placed over the first series. These were of sandstone masonry. The second occupation, of which only wall bases and floors were discernible, came and went and slowly reverted back to earth. Excavators considered the two lower occupations to have been those of Chaco-affiliated peoples. A single dendrochronological date of A.D. 1148 may have come from one of these levels, but exact provenience is uncertain. [11] That date is somewhat more recent than the range of twelfth-century dates from either the West or East ruins but suggests some degree of contemporaneity.

|

|

Figure 9.1. Ground plan of the Hubbard Site. (After Vivian, 1959, 6). (click on image for larger size) |

Following a period of abandonment, which Vivian felt may have corresponded to that which took place in the West Ruin as Chacoans moved elsewhere, a third utilization of the same ground took place. It is the disintegrated structures of this period that comprise the crest of the modern mound. As Morris predicted, these were a triple-walled, circular complex 64 feet in outside diameter consisting of a small, deep, central kiva and two rows of surrounding rooms. Whether the kiva ever was roofed is uncertain. It was not a Great Kiva as defined in other explorations, nor was it a tower as some suspected. It also was far smaller than many examples of similar constructions. During the second half of the twelfth century, the site had good astronomical alignment with Alkaid, just as did the West Ruin Great Kiva. [12]

Vivian considered the Aztec structure to be a Mesa Verdian building. He noted that the other most easily observed tri-wall of approximately 10 known examples is at Pueblo del Arroyo, Chaco Canyon, a village that also was reoccupied by persons of Mesa Verde Anasazi affiliation. Nonetheless, some archeologists regard both Hubbard Mound and the tri-wall at Pueblo del Arroyo as probably Chacoan. [13]

A surface scattering of cobblestones and considerable refuse did not relate to this tri-wall unit. Seven large bell-shaped pits lined with cobblestones plastered with mud were unearthed; more are believed to be undisturbed beneath untested portions of the mound and its vicinity. While such fire pits have a wide distribution in some areas near to the Animas drainage, their function is unknown.

Onstott did enough trenching in Mound F to show that it was of similar plan except that three rows of rooms enclosed the central kiva. Mound F was not cleared for visitor inspection.

Both the known tri-wall complexes at Aztec and a possible third just to the north of the East Ruin (Mound A) generally are thought to be late manifestations of the San Juan Anasazi. That opinion is now being questioned. The exact purpose of the tri-wall structures likewise remains debatable. Ceremonial aspects of an isolated kiva enclosed by rooms are counterbalanced by obvious domestic usage of the rooms. Vivian theorized that the units, scattered throughout the eastern San Juan Basin, were the turf of an incipient priestly class, which for a variety of reasons including status, lived near but not in the cultural center proper. [14] An intriguing observation of the symmetry of the layout of the Aztec tri-walls and the Great Kivas within the two house blocks does imply a formalized landscape concept for a ceremonial center. [15]

A trail leading from the northwest corner of the West Ruin to the top of Hubbard Mound allowed visitor viewing from above of 22 rooms, two kivas, and rudimentary wall features (see Figure 9.2). Visitors found the complexity of its superimposed features to be confusing, and the elements quickly ravaged the exposed structure. Since the site was not contributing to the meaningful visitor experience at Aztec Ruins and the methods used to stabilize it to withstand seepage and water drainage problems were not successful, after several decades, the major part of the Hubbard Mound was backfilled. [16]

|

| Figure 9.2. Hubbard Mound, a unique tri-wall structure, ca. 1954. |

EAST RUIN

Located about 150 yards northeast of the West Ruin, the architectural remains called the East Ruin are two adjacent mounds 16 feet high in places and more than 300 feet from east to west. After abandonment, the easternmost house slumped into a mound that was formerly thought to have been cut into along its eastern slope by an ancient channel of the Animas River but may have been mined for building stones by late nineteenth-century settlers. Otherwise, the heap of consolidated rubble lies virtually undisturbed under a shroud of rocky soil and thorny vegetation.

When first visited by valley settlers, the larger western mound was similarly densely covered with sage, greasewood, and saltbush. However, irregular sandstone masonry and cobblestone walls, some two stories, jutted through the mound's hardened shell at what appeared to be the northwest corner of a rectangular building. A series of long, weathered beams projected in a line from the north wall of the building at what seemed to have been a second story level (see Figure 1.3). Morris called this a balcony. The presence of subterranean chambers was indicated by sunken depressions in open plaza areas between the building's wings. It was a site inviting exploration, which apparently began in the 1880s.

In 1915, when Morris and Nelson scouted the area for a suitable site in which to excavate, they passed over the East Ruin. It already was potholed, particularly in some buried rooms with intact original ceilings. Morris himself did a little digging there that spring. As Vivian later noted, "...holes had been broken through walls in every direction in the hopes of finding further underground rooms, pits dug in the floors, and savinos [secondary beams] cut off for souvenirs." [17] Moreover, the men thought the settlement was not as large as that just to the west, nor was what was seen of its masonry of as high a caliber. To them, the East Ruin was of lesser importance.

During the years when American Museum of Natural History excavations were under way, Morris often engaged in after-hours probing elsewhere, which included the East Ruin. Once the title to Tract 2, encompassing the site, was acquired, Morris put a small crew to work to systematically clear some deposits to learn more definitely how they compared to those in the West Ruin. In all, 10 roofless rooms in the northwest corner were explored by the end of 1927, but no field notes survive.

Once the site was incorporated into the monument in 1928, there was no further digging in it for 30 years. Although the public may have been interested in an overview of an unexcavated pueblo of this magnitude, monument managers considered it too hazardous for visitation. Unstable walls and a number of depressions posed possible dangers to persons scrambling through the site. In 1946, some parts were backfilled to halt further deterioration.

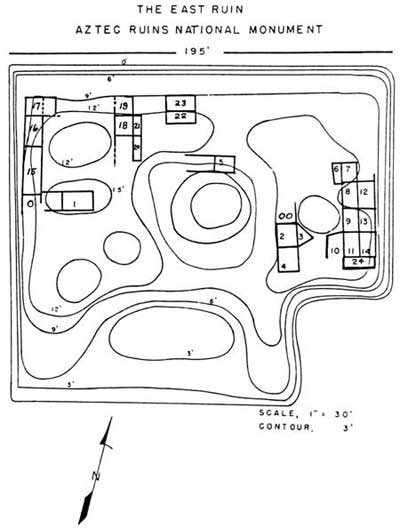

After World War II when the stabilization Mobile Unit was reestablished, Room 24 of the westernmost mound of the East Ruin was opened so that access could be gained to a series of nine first-story rooms in a block (see Figure 9.3). All had intact aboriginal ceilings much like those in the sister site. Weak timbers in these rooms were braced by new uprights. In 1957, the heavy overburden on top of the ceilings was removed, protective roofs were installed over nine rooms, and the interior fill of 14 rooms was excavated and hauled off. An inventory of 1965 listed 24 excavated and partly excavated roofed rooms in the East Ruin, one of which is a partially exposed kiva.

|

|

Figure 9.3. The East Ruin, Aztec Ruins National Monument. (After Richert, 1957, with additions). (click on image for larger size) |

On the basis of inferior construction as compared to parts of the West Ruin and a high proportion of Mesa Verde pottery recovered, Morris was convinced that the East Ruin represented a community of the thirteenth century when, according to his reconstruction of past events, Mesa Verdians flooded into the valley to reoccupy abandoned Chaco domain. There was no research done at the time contradicting this view. Morris's professional stature was such that a generation of National Park Service staff accepted this accounting without question. Roland Richert saw his finds of Mesa Verde ceramics in deposits cramming some rooms to a depth of many feet as further confirmation of Morris's interpretation. He regarded 10 cutting dates of dendrochronological samples ranging from A.D. 1115 to 1125, or exactly contemporaneous with the West Ruin, as reused wood. He believed three dates in the 1230s were actual construction dates for the East Ruin as a whole. [18] Five recently obtained 1200s dates from wood recovered in three rooms proves that at least parts of the structure were built during the final occupation. [19]

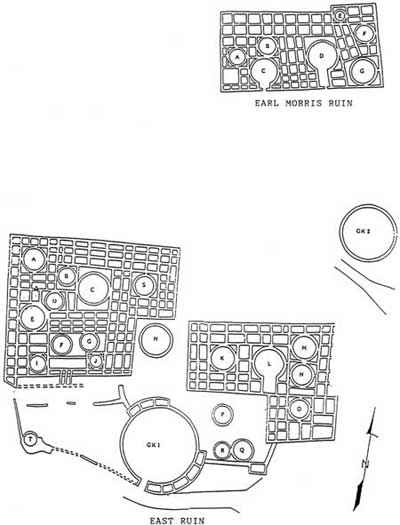

Nevertheless, questions about earlier judgments have been raised from time to time by the scientific community, no more so than now with the recent research at Chaco Canyon. The quality of the masonry of the East Ruin notwithstanding, it generally was done in the core-and-veneer Chaco method rather than the dimpled, double-block Mesa Verde style lacking a rubble hearting. The East Ruin appears to be of a size comparable to the West Ruin. Mappers recently preparing a preliminary ground plan of the former were able to discern approximately 122 rooms and 10 kivas in the western houseblock and 56 rooms and five kivas in the eastern houseblock. One of these latter kivas may have a Mesa Verde-style southern recess. Another four clan kivas were identified in the plaza (see Figure 9.4). Both the East and West ruins have a multistoried north tier of rooms, wings of room blocks at right angles to it incorporating a courtyard with a Great Kiva having encircling surface rooms, and an orientation to the south. Several possible features unique to the East Ruin are an earthen platform, walkway, and ramp. If similar constructions originally were present in the West Ruin, they were not recognized during excavations and may have been destroyed. The town plans of these two sites can be duplicated in a number of settlements in Chaco Canyon but not on the Mesa Verde. Perhaps the differences in construction can be explained by differences in personal abilities or standards. As to pottery, Mesa Verde wares were similarly more plentiful at the West Ruin. In both cases, that might be explained by longer Mesa Verdian tenancy, larger population, and perhaps burial customs. Only controlled excavations can answer the many questions about the East Ruin and how it interacted with its neighbor.

|

|

Figure 9.4. Map of East Ruin and Earl Morris

Ruin, based upon interpretations of a National Park Service concept plan, May

1989, by Andrae, Ford, McKenna, and Stein. (click on image for larger size) |

EARL MORRIS RUIN

This is an unexcavated, rectangular settlement at the extreme northeastern boundary of the original national monument, which is overgrown by rank vegetation as a result of waters overflowing from a farmer's pond and cultivated fields. A mapping project carried out in 1988 tentatively traced outlines of some 63 cellular chambers and seven kivas incorporated within the unit (see Figure 9.4). Between this village and the northeast corner of East Ruin, a circular depression suggests a second isolated Great Kiva, smaller than that within the East Ruin courtyard and lacking surface rooms. Peter McKenna, National Park Service archeologist working with the mapping team, believes a wall once existed that ran from Mound A to Mound C to the northeast corner of East Ruin to enclose a formal plaza west and south of the Earl Morris Ruin (see Figure 11.1). [20]

At present there are no plans to excavate the Earl Morris Ruin or incorporate it into the interpretive program. That development may come with implementation of the General Management Plan of 1988 (see Chapter 11).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006