|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 7: THE GREAT DEPRESSION AND CAPITAL IMPROVEMENTS

During the hard times of the 1930s, the United States government undertook programs to provide employment for its citizens by improving the facilities of all National Park Service installations in the Southwest. This included Aztec Ruins National Monument. As enacted, the legislation called for funded work to be completed within a very short period of time. Fifty years later many of the things accomplished then continue to enrich the public property.

CIVIL WORKS ADMINISTRATION PROGRAM

The condition of the West Ruin needed prompt attention. The pueblo was falling into disrepair faster than the custodian could put it back together. After every severe storm, portions of walls collapsed, endangering weakened adjoining sections. In his first monthly report, Faris said, "Because of the heavy wet snows and freezing and thawing the walls of ruins are falling or giving away almost daily and repairs mounting steadily." [1] The soft sandstone masonry of the structure was decaying slowly from moisture seeped upward by capillary action. The earthen mortar used by aboriginal masons was being eaten away. Such hazardous conditions threatened the old house, as well as the safety of those walking through the ruins. Faris grossly underestimated repair costs, originally requesting just $300 per year. [2]

The townfolks of Aztec were concerned. The president of the Aztec Chamber of Commerce wrote New Mexico Senator Dennis Chaves urging repairs. "A few thousand dollars used now will insure the original architectural beauty and effect for generations to come," he said. The editor of the Aztec Independent sent a similar letter to the other New Mexico senator, Bronson Cutting. A more formal resolution from the Chamber of Commerce as a body followed (see Appendix I). [3] These appeals prompted little immediate action in Washington.

While not dangerous, the appearance of the monument was unsightly. Once the compacted rind over the West Ruin cracked, exposed detritus that collected over the centuries was released to cause disposal problems for excavators. At first, the bulk of it lacking archeological significance was carried away from the vicinity of the site in order to make digging easer. Dislodged building stones and timbers were stockpiled nearer at hand in anticipation of future use in repair or restoration. However, during sporadic work in the 1920s, quantities of culturally sterile debris merely were shoveled outside of walls, where they banked against the three sandstone masonry sides of the village or lay in hummocks in the courtyard. Heaps of meaningless earth and rocks strewn about made it difficult for visitors to comprehend the ground plan and grandeur of the Anasazi town. In addition, the roofed utility rooms in the southwest corner of the house block, the storage shed, cross fences and extraneous buildings left from the days when Aztec Ruins was an integral part of an operating farm, and a barren landscape devoid of trees or shrubs detracted from the monument's over-all attractiveness.

Various civic groups and private citizens launched a lobbying campaign in the belief that both the ruin and local taxpayers would be helped by some attention from the government. The case for ruin repair and face lift was indisputable. Local residents felt that perhaps Washington bureaucrats were less aware of the misery that filled the Animas valley in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression. For many, jobs to supplement uncertain farm income were vital for survival.

The preliminaries to getting a combination relief and improvement program launched were filled alternately with hope and discouragement. Early in 1933, Faris went to work on a list of immediate needs. It was approved by the Washington office and then forwarded to Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, administrator of the Special Board for Public Works. [4] In summer, word came that Congress had approved a large appropriation for Aztec Ruins National Monument. [5] Pinkley sent Faris a list showing that Aztec Ruins was to get $32,000 under the National Industrial Recovery Act. [6] Job applicants besieged Faris. Weeks passed with no official confirmation of the appropriation. Finally, in despair, F.M. Burt, head of the Aztec Chamber of Commerce, wired the director of the National Park Service, saying, "We were informed weeks ago that thirty two thousand dollars had been allotted for improvement Aztec Ruins National Monument. We have large and growing list unemployed no relief in sight and winter approximately only sixty days away. Therefore earnestly implore you start work immediately if at all possible." [7] A same-day reply contained the disheartening news that a lesser sum finally approved by Congress ruled out the requested money for Aztec Ruins National Monument. [8]

The next ray of hope was a supplemental bill before Congress budgeting $10,000 for an administration and museum building at the monument. [9] The opportunity for the National Park Service to proceed with that improvement arose during the year when Morris moved out of the stone house to return permanently to Boulder. Because the tourist traffic through the yard disturbed him, Morris forfeited three years of his lease. Still pleading the cause for immediate employment of local men, Burt pursued this new proposal with another telegram to Washington. "Permit us, therefore, to urge with all the earnestness at our command and in the name and behalf of humanity that nothing be permitted to delay starting work at Aztec Ruins National Monument at the earliest possible moment and before winter comes." [10]

The next week the $10,000 appropriation passed, but it hit a snag. Since there was a statutory provision that no building in excess of $1,500 could be built in any federal park or monument, the Attorney General had to rule on its legality. At last, in October, a favorable decision was reached allowing expenditures to be made.

Still trying to get all he could for his monument and his neighbors, Faris aggressively went directly to the top of the Civil Works Administration hierarchy with a personal telegram to Ickes requesting further funding for improvements. As he wrote Morris, "The main idea of the work this fall is to create good feeling among the local people as much as possible." [11] In particular, Faris wanted to accomplish two immediate objectives by clearing away unwanted debris around the site and using it to fill quagmires in his hated "cowpath" of an entry road. The county road department agreed to this plan. [12]

Two weeks later Faris was informed that an allotment of $17,175 was available for Aztec Ruins National Monument through the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations. This grant came under the provisions of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (FP 503). [13] The amount was about half what originally was planned for the monument. The Farmington Times Hustler promptly reported the news: "Custodian Johnwill Faris, upon receipt of word that $17,175 had been allotted for repair work on the Aztec Ruins, has commenced plans for preliminary work to begin as soon as the funds are placed to the credit of local officials. Mr. Faris has stated that much of the repair work cannot be done until spring, but that he expects to work fifteen men for a period of six weeks this fall and hopes to have the men on the job before another week passes. Minimum wages will be 45¢ per hour, working a five day week of six hours a day. This is the first relief appropriation Aztec has received and is expected to give needed employment to a part of the jobless of the county." [14]

Even though he lacked authorization to do so, Faris wasted no time in hiring a crew of 16 men. With alarm over Faris's penchant for crashing onward, Superintendent Pinkley tried to clear this hasty action with the National Park Service director. The director on the same day returned instructions to have Faris stop work immediately. [15] At the moment, officials in Washington were trying to engage the services of Earl Morris, on loan from the Carnegie Institution, to direct the repairs for which the funds were intended. Faris remained determined to provide some employment. On November 22, he wired Director Hillory Tolson that he was acting on advice from Morris as where best to put his crews to work cleaning up the grounds and gathering stone for planned restoration. He pleaded that he be allowed to keep the men at work while the weather continued good. [16] Financial relief was desperately needed. A return telegram gave him that permission. [17]

The Civil Works Administration program for Aztec Ruins was in effect from December 6, 1933, to April 12, 1934, a relatively brief time for work contemplated. The total allotment amounted to $23,880, of which $20,165.24 actually was committed (see Table 7.1). [18]

|

Table 7.1. Civil Works Administration Program Statistical Summarya Project | ||

| 1. | Barn removal | $ 829.58 |

| 2. | Fencing monument | 1,769.67 |

| 3. | Parking area | 8,742.81 |

| 4. | Clean-up and landscaping | 7,722.03 |

| 5. | ---- | |

| 6. | Archeological work | 1,101.15 |

| Total | $ 20,165.24 | |

a National Park Service: Aztec Ruins National Monument files at the National Archives, Washington. | ||

Two weeks after Faris received authorization to proceed beyond his initial hiring, 63 men and two women were on the payroll. Washington questioned the large number of employees because some of the work was on a road off the monument. [19] Instead of full-time employment as expected, the government imposed a 15-hour weekly limit so that more individuals could share the available funds. The number of employees declined as various assignments were completed until, at the termination of the program, there remained just a seven-man crew. Pinkley and Faris praised the diligence with which individuals responded. Everyone was grateful to be gainfully employed. [20]

Six interrelated projects made up the package of goals to be accomplished under the Civil Works Administration program.

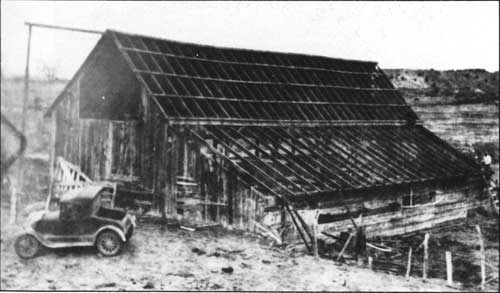

(1) Project 1, under direction of seasonal ranger Thomas Thompson, moved the Abrams hay barn from the edge of the East Ruin to a location on the family farm selected by Orrin Abrams, replaced its worn siding, treated the structure with old motor oil, and baled loose hay stored in it (see Figure 7.1).

|

| Figure 7.1. Abrams hay barn being dismantled for removal from the monument, 1933. |

(2) Project 2 removed interior cross fences surrounding individual parcels and, through contract with the Santa Fe Builders Supply, installed a new outer boundary fence of 47-inch woven wire with a single barbed strand at the top. [21] The north boundary fence was erected with flood gates and rock dikes. In times of sudden rushes of water downslope, the gates could be opened. The dikes hopefully would divert water into a nondestructive course. Post holes on the fence lines hit some evidence of former occupation. The fences were a measure taken to keep livestock off the monument. [22]

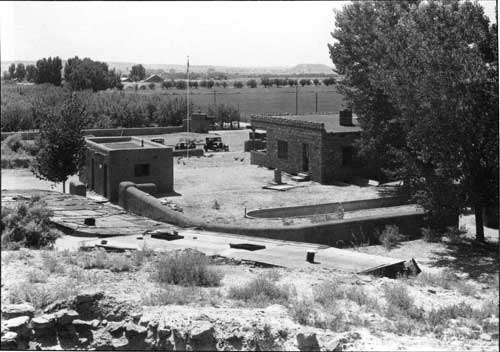

(3) A large piece of ground at the south end of Tract 4, a prehistoric trash mound, was removed as Project 3 so that visitors could park. Because of ground frozen in December, the building of a parking lot there was difficult. Workers turned the sod with hand plows and teams of horses in the late afternoons when the soil was warm; they graded the areas the following mornings. They spread a rock base for future pavement on top of the smoothed soil. Because of the cold, engineers decided, rather than using adobe bricks, to construct the walls surrounding the lot of rock rubble plastered to resemble adobe. Sand and mortar water were warmed in drums and boilers set over bonfires. A curbed island formed the center of the lot. Designers placed an ornamental gate at the entrance (see Figures 7.2 and 7.3). [23] At a cost of $8,742.21, the parking lot was a bigger investment than yet had been made to serve the monuments for which the facility was established.

|

| Figure 7.2. View of 1933 from southwest corner of the West Ruin showing roofs of three aboriginal rooms put to modern purposes, the comfort stations, the Morris house, the cistern pump at one side, the cement-lined pond at the rear, and the walled parking area in front. |

|

| Figure 7.3. Parking lot in front of Aztec Ruins National Monument headquarters, ca. 1934. |

(4) Project 4 was the cleaning of areas around the ruins of dead brush, sticks, old lengths of barbed and woven wire, and trash, and hauling off unwanted earth (see Figures 7.4 and 7.5). [24] The dense vegetational cover developing in the northeast sector of the preserve as a consequence of overflow irrigation waters was not permanently eradicated. As another aspect of this project, Tatman led an archeological reconnaissance and survey of the monument. He was in charge of partial or complete excavation of six rooms, six kivas, a two-roomed extramural structure, six burials, and the trenching of the southeastern refuse mound. Some of the results of these activities are discussed more fully below. [25]

|

| Figure 7.4. Relays of horse-drawn wagons hauling debris from West Ruin to fill ruts in entrance road, 1933. |

|

| Figure 7.5. Removing debris from West Ruin courtyard during clean-up effort, 1933. |

(5) Project 5 was the creation of a picnic ground on the southern Tract 3. In 1933, workmen prepared the spot but, since it was in oats, the planting of trees was postponed.

(6) Project 6 was the restoration of recovered fragmented pottery and the cataloging of archeological specimens. Upon the recommendation of Morris, Alma Adams, a young lady from Boulder, undertook the painstakingly slow pottery work. [26] Her expertise merited a salary of $1.00 per hour. [27] Because the $300 allotted for ceramic restoration was exhausted before she completed all the vessels, the Carnegie Institution provided funds for an additional month's effort. Adams's technique involved repainting the vessels after they were reassembled so as to duplicate their former appearance. Because the original fabric is obscured, such total restoration now is considered improper for archeological specimens. A number of photographs of vessels arranged on tiers of cloth-covered shelves may have been meant as documentation of her work. Adams's assistant was Janet Case, who was responsible for the cataloging. [28] One result of the efforts of these two women was that government relief funds were expended on artifacts belonging to a private institution. The American Museum of Natural History had neither loaned nor given the pottery to the government, but it was repaired and included in the monument catalogue.

Cleaning Up the Monument

The clean-up project was the one that was most readily to change the appearance of the monument. It was necessary to proceed cautiously so as not to disturb any unknown ancient constructions outside the great house and not to remove talus that might buttress weak walls. Since in that part of the ruin there was little danger of outward thrust from pressure of deposits within the rooms, Morris suggested taking away debris from the north side of the house block up to the walls of the building. The excavated rooms or those having original ceilings served to anchor walls in place. The last level of occupation was established in the excavation of the northeast corner and was to be followed throughout. On the west side of the house, Morris advocated caution. He thought it probable that in that area there were flimsy structures not visible on the surface. [29] On the east side, there was likelihood of much reusable stone. An insufficient amount of building blocks had been recovered previously in that sector to account for the fall of several stories of the building. In 1917, a trench was dug outside the east wall to permit masons to reset the stones. The ditch was backfilled, forestalling possible disintegration upon removal of outer talus. [30] In the court, Morris suggested that piles of earth dumped on the east side of the Great Kiva excavation should be removed in anticipation of work to commence there the next spring. [31]

Twenty-one men with three teams of horses and six wagons went to work to finish this part of the general program by the end of 1933. Photographs of the period show a relay of wagons moving up and down the road leading to the ruin to deposit their loads in numerous pot holes (see Figure 7.4). [32] A horse-pulled grader transferred from Mesa Verde to Aztec leveled out the dirt. [33] The desired reserve of building stones did not materialize. [34]

Foreman Tatman's report on the clearing operation stated that the building stone was saved, and the dirt was taken to washes and low spots for proper leveling and landscaping. All debris was removed from around the Great Kiva. The stone was sorted into refuse, rough stone, and facing stone. Refuse or disintegrated stone was discarded; the rough stones and facing stones were saved for ruin repair. All told, 2,900 wagon loads of spoil materials were hauled away. [35]

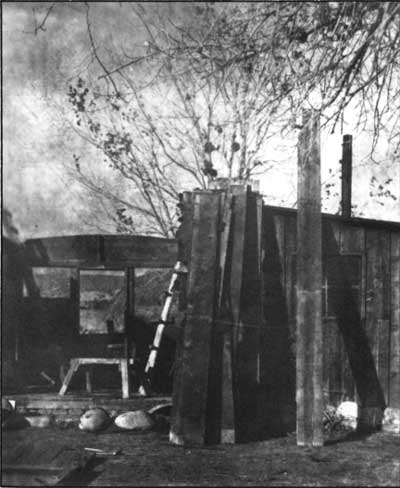

As part of the clean-up campaign, the American Museum shanty behind what had been the Morris house was dismantled partition by partition and moved to the property of a former workman, Arthur Lawson, by the iron bridge across the Animas (see Figure 7.6). Paul Fassel moved along with it and continued to occupy the structure for some years. It now serves as a bait shop. [36]

|

| Figure 7.6. Dismantling the American Museum storage shed at rear of Morris house, 1934. |

Beautification of the monument setting as part of this project undoubtedly resulted in unintentional wholesale eradication of archeological resources and irreversible alteration of the prehistoric landscape. The old Animas River channel at some earlier time had cut a deep swath along the east boundary of the monument. It left behind a high embankment and a wake of uprooted, matted vegetation. Of more concern to archeologists was that it impinged upon the easternmost mound of the East Ruin complex, perhaps exposing structural elements and artifacts. Morris used the area slightly to the south of the ruin itself as a dumping ground for some of the fill from the interior West Ruin rooms. The solution in the 1930s to making this part of the monument more pleasing in appearance was to cut down the terrain and redeposit several thousand yards of earth in low spots and arroyos along the eastern perimeters of the preserve. Doubtless, hundreds of inconspicuous specimens went with the dirt. Proudly, Faris reported that all the land surrounding the visible ruins was plowed and harrowed, 400 native trees and shrubs were planted, and the irrigation ditch across the south was rocked. [37] With those actions, any traces of ancient roadways, waffle gardens, or earthen constructions were erased. Ironically, those clean-up measures cost the taxpayers seven times the amount devoted to concurrent archeology at the monument.

Excavations

Excavations were done in order to make safer trails, to repair walls, to obtain building stones for reconstruction purposes, or as a result of various new constructions exposing prehistoric features. Tatman was overseer of a six-man crew under the general direction of Morris. One young man on the team was Robert Burgh, borrowed from the coeval work at Mesa Verde. He later became a laboratory assistant to Morris in Boulder. [38]

To prevent collapse, a weighty layer of windblown sand and decayed ceiling elements was taken from second-story Room 2022. [39] Pressure needed to be removed from the intact ceiling of the ground-level room below. No small artifacts were present in the fill.

Morris's Room 203 (current number, Room 249) in the North Wing contained 17 feet of fill. This was removed to make access easier to the first-story museum rooms. The crushed skeleton of a small child with wrappings of feather cloth and plaited rush matting was on the floor. The burial body reposed on a mat of peeled willows with flattened side upward. Above these remains, about a five-foot deposit of wall stone was thrust across the chamber when the north boundary of the room split at the bottom and collapsed. The crushed timber of the second floor covered the stone. On the second floor was a small accumulation of refuse, the most conspicuous element of which was a mass of corn tassels done into small bundles tied with a twined lacing of yucca strips. Charred remains of the ceiling of the third story lay above the earth, which had formed the floor of the second. The remainder of the fill was composed of stone and adobe, resulting from the gradual disintegration of the upper walls. Tatman's crew recovered bone awls, bone cylinders, potsherds, and a quantity of lignite, such as was used for the manufacture of beads and ornaments. [40]

Tatman then turned to five rooms in the southwest corner of the house block in order to further understand this sector of the village. Room 151 forming a southwestern limit was a narrow corridor about 85 feet long west to east with a hall-like southward extension at its western end. Reminiscent in its length of some similar features in Chaco Canyon, for a number of years this passage was used by the National Park Service as an entrance to the pueblo's central courtyard. Whether it functioned in Anasazi times as a passage from the outside to the village center is uncertain. There also is a probable entrance through the line of southern cobblestone chambers. Associated rooms (209-212) were only partially intact. [41] They contained some adobe walls in which reinforcements of two-inch poles were laid horizontally in mud alternating with layers of brush and sticks. Occasionally, small straight sticks were inserted as a layer diagonally through the walls. The construction method was not unlike that used for the four massive square columns supporting the roof of the Great Kiva. The method of execution in the domestic units was less precise.

In an area intensely occupied for at least two to three centuries, cultural materials were present wherever digging was done. As work continued around the monument, random finds were a small two-room cobblestone structure 24 feet northwest of the northwest corner of the West Ruin; a skeleton farther to the west of this dwelling accompanied by a Mesa Verde mug, bowl, and corrugated jar; a portion of a cobblestone wall beneath the north wall of the new parking lot; the ventilator shaft and southern recess of a kiva beneath the east wall of a patio created behind the house; a boulder-lined firepit, 24 by 38 inches, dug to a depth of 28 inches south of the village retaining wall; and six burials and associated pottery between Kiva A2 [Annex] and a trash heap to its southeast. [42] Individually, none of these finds contributed much to the history of the site, but together, they confirmed earlier discoveries.

The open expanse of the courtyard that formed the heart of the village was trenched during the Civil Works Administration work so that a large drain tile could be laid diagonally from higher ground in the northwest to lower ground in the southeast. The drain was needed to carry off ground and storm water endangering the friable sandstone walls of the various building units. Workers cutting the trench hit three subsurface kivas of various sizes. Their finding cemented Morris's earlier opinion that the court was where the cultural sequence of the site eventually could be delineated. [43] On behalf of Morris, Nusbaum sought authorization from the director of the National Park Service to excavate any archeological features exposed during the drainage work. Because of the danger of loss of scientific data, this aspect of the project, not spelled out earlier, could not be ignored. [44]

What appeared to be either an unfinished or dismantled Great Kiva, some 40 feet in diameter and situated just northwest of its excavated counterpart, was the most spectacular of the previously unsuspected structures in the courtyard. It was under portions of three surface chambers forming a ring around the known Great Kiva.

The trenchers happened on to two small kivas more than nine feet beneath the last used court surface to the east of the excavated Great Kiva. In Morris's opinion, both were of Chacoan derivation, with multiple layers of smoke-blackened plaster indicating long usage. One was in the part of the site where Morris began his explorations in 1916. Since it was isolated from adjoining house remains, it had been overlooked. Workers found a third small kiva with a pronounced southern recess of a Mesa Verde style 10 feet below the court surface almost abutting the east face of Kiva E, excavated and reroofed in 1917. Despite its Mesa Verdian attributes, pottery scattered on its floor was of a Chacoan tradition. Other explorations in the courtyard found an abandoned, filled, small kiva under Room 166, a surface chamber in the southern arc of rooms around the excavated Great Kiva. Morris assumed that this lesser room was an earlier Chacoan construction.

Only one ceremonial room within the house block, Kiva T, was examined in the Civil Works Administration effort. Morris regarded the kiva, poorly built, as a Mesa Verdian remodeling exercise. [45]

PUBLIC WORKS ADMINISTRATION PROGRAM

As the Civil Works Administration program was phased out, funding on a broader scale came from another new agency, the Public Works Administration. Ruins repair, the restoration of the Great Kiva, and the construction of an administration and museum building were under its jurisdiction. The parking lot was carried over from the Civil Works Administration program. After basic construction, it was paved with an extra allotment of $6,000. [46]

Ruin Repair

In 1916, it was not expected that the West Ruin would be eaten away by waters from an upslope irrigation ditch. This situation was exacerbated by a naturally high water table in the valley. Apparently, a threatening condition did not exist prior to excavation, as the wealth of dry perishables retrieved from some rooms attested. Other parts of the great house also were moisture free. Morris noted, "When the roofed kiva at Aztec [Kiva E] was excavated the earth was as dry as earth could be." [47] But that changed. Exposure, saturation of the subsoil, and expanded farming caused underground water to work through capillary action up into a foot or more of walls, weakening them at their foundations and leading to exfoliation of the lower masonry courses. Although repair work was done in tandem with excavation, by the 1930s, it was proving to be impermanent, ineffectual, even destructive.

In early 1933, Engineer James B. Hamilton came to Aztec to appraise the situation for the National Park Service. While he felt that earlier repair efforts halted or slowed some damage, the cement used was not reinforced nor provided with expansion joints. As it aged, it cracked extensively, thus permitting water to reach into cores of walls or soak ceiling wood. Up to that time, no means of coping with the irrigation water were tried.

Because protection or repair of Southwestern ruins was something new to the National Park Service, it was a time of experimentation. Hamilton only suggested a few obvious ways to attempt control of these ills. These measures were replacing old wall cappings with more effective materials, redoing cement covers over intact ceilings or remodeling those in fair shape, installing tile-lined drainage trenches to lead water away from weak walls, putting fans or sump pumps in damp kivas, and experimenting with substances that could be sprayed or painted onto wall surfaces to waterproof them. [48]

By 1925, Morris already recognized that reroofed Kiva E was a special problem. [49] In the Anasazi manner, he had covered the steeply pitched, cribbed, cedar poles of the superstructure with packed earth. To protect that layer, he had added a heavy concrete slab topping. Above that as further protection, carpenters erected a shell of lumber and tar paper. Over time, the concrete slab beneath the uppermost roof sagged and cracked. Further, seepage encroached on the chamber. Morris reported, "...a damp spot appeared at the foot of the north wall and in the course of two years it spread entirely across the kiva floor southward and rose up on the side walls." [50] The National Park Service managers considered the kiva an eyesore and a hazard. Because they wanted to use the structure as a possible lecture room, they felt something had to be done to make Kiva E safe and attractive. As often was the case, there was no money.

In 1934, Hamilton recommended that the cement and tar paper roofs of Kiva E be stripped down to the cribbed logs. A new watertight roof should be raised over the logs, leaving an air space between roof and logs to prevent dry rot. Then, the whole construction should be covered with earth so that it would resemble the original model. He asked that an objectionable wooden railing leading to the kiva hatchway be eliminated. [51] Hamilton thought a drainage system or sump pump would take care of unwanted moisture that was sure to increase because test holes showed water about three feet below the kiva floor. [52]

Using Hamilton's proposals as a plan of attack and Morris's archeological advice, a Public Works Administration repair crew started work in March 1934. Their first priority was digging a drainage ditch across the courtyard of the West Ruin. In places, they trenched as much as 17 feet below the surface in order to take the drain at least three feet below the floor of Kiva E. A large tile tubing was put in the trench. This was covered with gravel hauled by two teams and a wagon. [53] The tubing was connected with drains from the roof of the Great Kiva and edges of Kivas E and I and was extended some distance southeasterly out of the courtyard to emerge at ground level. There, collected water was allowed to soak into the earth. The planners hoped the small opening would prevent animals from entering the system. [54] To complete the job, workers filled the trench with the excavated dirt and straw. The tendency of these materials to hold water and work into the lines made this action a mistake. Kiva E did dry more than it had for several years, but that was only a temporary condition.

Even though engineers saw that the length of the drainage excavation was cribbed, its construction was hazardous. Unknown, unstable, subterranean kiva and room walls beneath the modern surface sometimes unexpectedly gave way. One near-tragedy occurred when a man standing in the bottom of the trench was engulfed in a thundering cloud of earth crashing down upon him. His fellow workers furiously pushed off the dirt to free his head. They put a large wooden box over him to shield him from additional fall until they could get the lower body free. Morris explained, "They had been digging a continuous trench. I suggested that instead of doing this they sink pits just long enough to give plenty of room to work in, timbering them well as they went down, about ten feet apart. Then when bottom had been reached to tunnel through from one to the other. This they did and no more cave-ins occurred." [55]

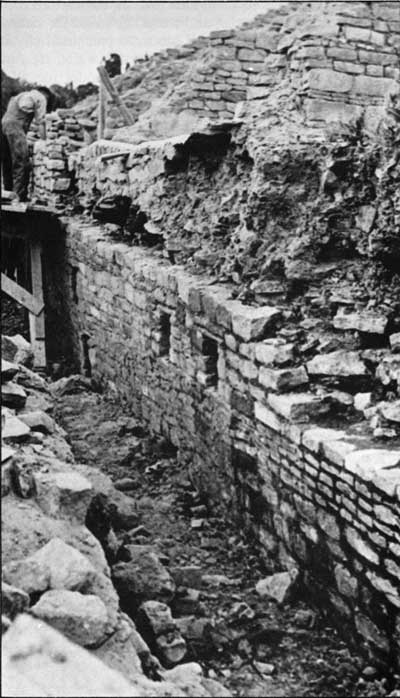

Public Works Administration repairs concentrated on the northwest part of the village. The outer north wall was in such deplorable shape that water worked its way into rooms used as a museum, dampening lower stones and dirt floors. Exterior veneer loosened from the wall core or fell. As a flood control measure, workers scraped earth and debris well back from this corner and then hauled it away. They removed the facing stones for 117 feet of the north facade from the northwest corner, working vertically from a height of nine feet down to the foundation (see Figure 7.7). The stones were reset in cement. [56] The exterior base of the wall remained six to eight feet above the level of floors of first-story rooms inside the building. The men installed a drain system with vitrified tile to the north of the ruin after auger holes confirmed the soil's heavy moisture content at about a depth of 12 feet. [57] The drain ceased to function properly and was abandoned after several months.

|

| Figure 7.7. Resetting exterior wall of North Wing, 1934. Rubble core and shaped sandstone veneer evident. |

For 97 feet from the northwest corner, the west village wall at a height of about seven feet was dismantled and redone in similar fashion. [58] In that case, the men banked earth against the lower part because rooms inside had not been cleared. This helped direct water away from the house. Faris reported that matching the green stone bands along the west wall was tedious and slowed the effort. [59]

Morris's report on the 1934 ruin repair work described other important accomplishments. He estimated that 2,100 square feet of wall face was repaired or rebuilt at a cost of $1.16 per square foot. In a slow effort to duplicate the fine aboriginal masonry, the northeast arc of Kiva L was refaced for a length of 20 feet to a height of three feet. Veneer of half of Room 249 was replaced. [60]

Hamilton tried a new technique to preserve ceilings. He installed a reinforced concrete evaporation basin in second-story Room 2022 in the North Wing and remodeled the previously existent concrete floor of Room 1962, also to serve as an evaporation basin, by the removal of wall stones and the casting of a reinforced rim around the edge of the older concrete slab. This was an experiment in order to avoid having to remove damaged concrete slabs installed by the American Museum crews. To Morris, the experiment was unsuccessful. The new basins did not remain watertight. [61]

Nonetheless, two years later Faris requested a sum of $4,700 to cover 20 rooms with the reinforced concrete roofs of the catchment type designed by Hamilton. He disagreed with Morris regarding the success of the earlier experiment. [62] No record that this work was carried out has been found.

Although Hamilton was in charge of daily repair work, a visiting National Park Service engineer wrote the director, "I am very impressed with the thorough, commonsense, and cooperative way in which Mr. Morris is proceeding with this work. We as engineers are looking forward to learning much in the coordination of engineering methods with archeological preservation and restoration from him." [63]

The repair task at Aztec Ruins was so enormous that six weeks into the project it was obvious more money was needed. Morris appealed for an additional $24,600. He cited the need to cap 4,500 linear feet of wall, to protect 6,000 linear feet of wall bases, to patch and chink 15,000 square feet of walls, and to remove 12,500 yards of earth from around exterior walls. He further argued that repair measures being tested at Aztec Ruins would provide a future model for all National Park Service monuments with antiquities. [64] Knowing that an appropriation bill for additional Public Works programs was then before Congress, Faris fired off his own request for $25,000. [65] After personally inspecting Aztec Ruins National Monument, Assistant Director Demaray agreed that Morris easily could invest from $5,000 to $18,000 in its immediate repair. [66] However, the top project was to be the restoration of the Great Kiva, for which $10,000 of the original $17,175 allotment was earmarked. Otherwise, $7,000 already had been expended on the various aspects of the over-all program. That left little to complete the other things that Morris felt were necessary. His request was denied. [67] Thus, repairs that were essential to the ruin's preservation were not done. That caused a good deal of resentment among those given this responsibility. Cement, reinforcing steel for the roof of Kiva E, and other supplies were stockpiled. What was lacking was money for labor. [68]

Because Morris was in charge of repairs going on at Mesa Verde at the same time he was overseeing similar projects at Aztec Ruins, he succumbed to the temptation of sharing materials between the two areas. The most questionable instance of this happened when Al Lancaster noted in his field notes for work being done at Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde, "In afternoon helped Mr. Morris mud around beams in Speaker Chief Tower. Beams brot [sic] from Aztec." [69] Very probably the beams in question were recovered during the clean-up or excavation jobs under way at Aztec and were unprovenienced. However, their transfer out of context to a different Anasazi region compromised their usefulness for dating purposes.

Great Kiva

When the Great Kiva was cleared in 1921, there was no money to fix its slumping walls and floor features or to cover it in any way. Three years later, after the Aztec Ruin was the property of the government, Morris notified the American Museum of the rapid deterioration of the structure, saying:

Of repair the ruin needs a great deal. In my opinion the most desirable portion of it would be the placing of the House of the Great Kiva in a condition comparable to that now existent in the East Wing of the ruin. The masonry of this structure is badly disintegrated, and most of it would have to be taken down and rebuilt. Fully $1500 would be necessary for this work. [70]

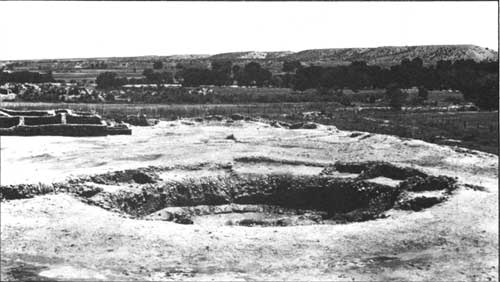

Ten years later the Great Kiva became an offensive tumble of stones and a pond of standing water after every rain (see Figures 7.8 and 7.9). Hamilton reported that the Great Kiva in 1933 had "lost almost all form and outline." [71] He recommended the restoration of the Great Kiva, using the Morris report of 1921 on its architecture as a guide and suggesting that $1,500 be set aside specifically for this purpose. [72]

|

|

Figure 7.8. Great Kiva after excavation in 1921 (Courtesy American Museum of Natural History). |

|

| Figure 7.9. Deteriorated condition of Great Kiva prior to reconstruction in 1934. |

Morris was appalled at the low estimate of costs to put the Great Kiva into acceptable condition. Although 10 years previous he also had used the $1,500 figure as an estimate, in 1933, he believed that the proposed budget would pay to replace less than half the existing walls to their height at that time. "The ideal thing would be completely to restore the Great Kiva," he stated, "replacing its roof, and making available to the public an example of the most intricate sort of sanctuary that was ever developed by the Pueblo people. To do this as it should be would require a probable expenditure of $10,000, with $8,500 as an absolute minimum." [73]

Director Arno Cammerer responded to the idea of totally rebuilding the Great Kiva, rather than merely repairing it in its incomplete state, by asking John C. Merriam, director of the Carnegie Institution, to loan the National Park Service the services of Morris. Cammerer wanted Morris to supervise all the repairs and restoration work at Aztec, as well as carry out some remedial measures on cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde National Park. This action was approved in November 1933. The following April, Morris was appointed a collaborator-at-large in the National Park Service. His salary was paid by the Carnegie Institution, and $5.00 per diem was handled by the National Park Service. [74]

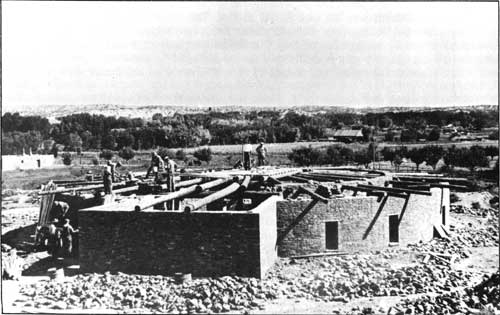

While trenching for the courtyard drainage ditch was going on, preparations for the reconstruction of the Great Kiva commenced. Seasoned timber for roofing the Great Kiva was cut and hauled from the San Juan National Forest. At the monument, laborers peeled and sawed logs to proper lengths for the various roof, lintel, and ladder elements. Additional shaped sandstone blocks were hauled from a Chaco outlier site in the La Plata valley that Morris dug in 1930. A water softener was installed so that uncontaminated water could be used to mix mortar. The fallen materials that clogged the Great Kiva were removed. Meanwhile, Morris went to Chaco Canyon to learn what he could about architectural details from opened Great Kivas there. With disappointment, he reported, "The result was largely negative, hence I shall have to rebuild guided entirely by local evidence." [75] Two colleagues, Alfred V. Kidder and Jesse Nusbaum, came to Aztec to confer with Morris about how to confront this unique problem. As Chairman of the Division of Historical Research at the Carnegie Institution, Kidder was Morris's superior; Nusbaum was archeologist for the Department of the Interior.

In late May, an unparalleled effort in the history of Southwestern archeology was begun with the reconstruction of the Great Kiva. [76] Dismantling walls and resetting the stones in cement was a routine process that had been followed at Aztec Ruins since work began in 1916. Several of the 1934 crew, who had been participants in the American Museum of Natural History excavations for one or more seasons, could go forward without much direction. Very soon, however, they learned that one factor not recognized in the earlier excavation was that two benches encircled the Great Kiva at its floor level. A Mesa Verdian remodeling covered a more carefully crafted, earlier Chaco bench. With that discovery, Morris decided to restore the Great Kiva as it was built originally. [77] It was later determined that the orientation of the building at the time of use was in alignment with Alkaid in the Ursa Major, a constellation of importance to modern Pueblos in certain agricultural ceremonies. [78]

By June, Faris reported that the subterranean chamber with its floor elements and the rooms spaced around it at ground level were taking shape. [79] There were two entrances to the central chamber on the room's primary axis. One was through the altar room on the north, and the other was in the south wall. Because they were seen in similar configuration elsewhere, scientists did not question the accuracy of the restoration of the two so-called foot drums and the fire hearth on the kiva floor. The rungs of ladders leading to the surface rooms inset within the upper walls of the subterranean portion of the chamber and the altar platform in the north surface room were questioned. Nevertheless, Morris felt then and for the remainder of his life that there was ample archeological justification for his reconstruction of all aspects. [80] After a visitor fell and broke a leg descending the inset stairs from the north room to the kiva floor, maintenance workers placed wooden staircases with rails at the north and south entrances. [81]

Four columns three feet square rose to an estimated 18 feet to support a massive, flat, circular roof of approximately 90 tons in weight. [82] It was this part of the reconstruction that raised most questions among archeologists, who never had visualized such a sophisticated piece of architectural wizardry being executed by the relatively technologically unadvanced Anasazi. The columns themselves demonstrated a rather remarkable basic engineering knowledge. They were constructed of masonry courses interspersed with series of cross-bedded poles laid in alternating directions, which withstood movement as occurs in columns and in a large unbraced structure of this kind. Furthermore, each pillar in a subfloor, masonry-lined cist six feet deep was seated on a stack of four ponderous circular slabs of stone three feet in diameter. The cists rested on a deep base of compacted lignite, below which was a foundation of cobblestone and sandstone in adobe. This composited underpinning prevented the combined weight of pillars and roof from sinking into the ground upon which the kiva rested. The placement of the pillars in a square in the outer circumference of the kiva precluded a cribbed superstructure such as those on smaller clan, or residential, kivas. From the pattern of burned ceiling residue recovered on the kiva floor, Morris theorized radiating logs extending like spokes of a wheel from this central square to the outside walls of the surface rooms. Over this framework, shorter lengths of timbers were spaced in cross pattern. As in domestic ceilings, these were covered with shredded cedar bark and a foot of tamped earth.

After two and a half months and many decisions about the intentions of the prehistoric builders, the Great Kiva was nearing completion. Morris told Kidder that the inner wall and the pillars of the Great Kiva were finished. The outer wall was well above ground. He said that the weighty disks beneath the four columns set on a bed of coal shale duplicated identical methods at the Chaco ruin of Chetro Ketl. He was pleased that after examining a single beam in the wall of one of the floor vaults, Douglass read a date of A.D. 1131. [83] That placed the first construction of the sanctuary within, or perhaps a decade later than, the time span of the great house behind it. [84]

Throughout his association with work at Aztec Ruin, Morris continually ran out of money with which to complete a given task. In July 1934, he found himself in the same predicament in regard to the Great Kiva. With only enough money to carry the work through two more weeks and the roof not yet in place, he appealed to Merriam at the Carnegie Institution to ask Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes personally for an additional $2,500. [85] Ten days later Merriam forwarded the request to National Park Service Director Arthur E. Demaray. Demaray advised Ickes, "In the event this request is approved, it will provide for the proper completion of a memorial to the ingenuity of a prehistoric people in a creditable manner and protect the investment already made by the government in the restoration of the House of the Great Kiva." [86] Within a few days, he had to tell Morris that no more money would be supplied by the Public Works program. [87] Faris wrote directly to Ickes in the interim. [88]

Discouraged, Morris told his troubles to Kidder. The Great Kiva was standing with major ceiling logs in place but lacking both roof and plaster finish (see Figure 7.10). He doubted that Ickes would respond favorably to appeals for help. [89] It seemed he was right when the first reply from Washington was that the only monies available were those unused on some other phase of the general project. [90] These funds did not exist. On August 15, just $70 remained uncommitted.

|

| Figure 7.10. Erection of roof on restored Great Kiva, 1934. Custodian's residence at left center. Tatman's apple orchard at right center. Village of Aztec behind trees at upper center. |

Two weeks later, the request for supplemental money for the Great Kiva unexpectedly was approved. [91] Not wanting to see the work halted before completion, Kidder already had secured permission from the Carnegie Institution for the loan of a light truck and six weeks wages for two men in order to finish the roof under the direction of Gustav Stromsvik, a Carnegie Institution employee who had worked with Morris in Yucatan and Canyon del Muerto. On October 10, the allotment was reduced to $2,250, a setback that immediately sent Faris to the Western Union office with another plea to the director of the National Park Service. The next day the full amount was restored. [92]

In October, the finishing step on the Great Kiva was coating the interior with cement plaster and painting it. A dark red wainscoting below an upper expanse of white duplicated the typical scheme found on domestic quarters and recovered in small traces in the excavation of the Great Kiva. John Gaw Meem, a Santa Fe architect familiar with Pueblo architecture, provided a formula for the red concocted from modern ingredients that would be more permanent than the hematite used by the Indians. [93] Morris supplied a small sample of the red to redo a wall mural in the tower of Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde. He lost a second request for $7,500 to place a reinforced concrete or composition roof over the less durable copy of the aboriginal one. [94]

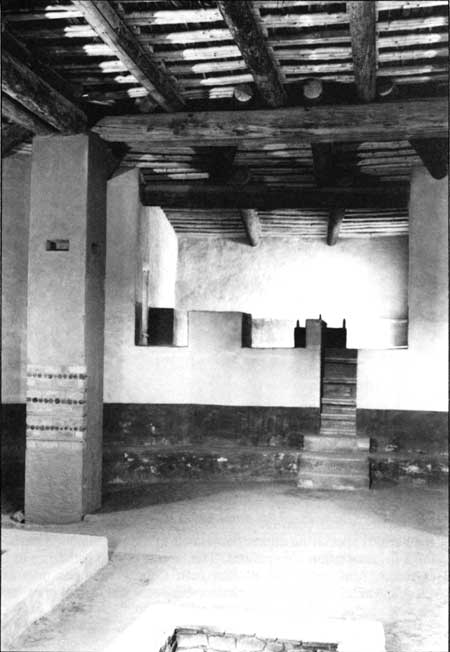

The excavation in 1921 of the Great Kiva took a small crew six weeks working on a shoestring budget. Its restoration 13 years later required five months' work by a large crew and considerable cash outlay (see Table 7.2). [95] Together, the two operations were unusual in being the responsibility of one scientist. Because of that, the Great Kiva in one sense is a memorial not only to the Anasazi but to Morris. The present National Park Service policy rejects this sort of total rebuilding, but unquestionably laymen have a clearer idea of how communal kivas looked when they were in use (see Figures 7.11 and 7.12). That was Morris's goal. Its maintenance added to the preservation burdens of the National Park Service.

|

Table 7.2.Public Works Administration Program Statistical Summarya | |

| Restoration of Great Kiva | $ 12,450.76 |

| Drainage of Ruins Court | 2,961.18 |

| Patching, Restoration, and Capping Walls | 2,358.88 |

| Protection of Original Ceilings | 660.86 |

| Protection of Roof of Kiva E | 173.38 |

| Protection of Museum against Flooding | 198.88 |

| Restoration of Pottery | 480.12 |

| Clean-up | 390.94 |

aJ.B. Hamilton, Final Construction Report on Repair of Ruins, May 31, 1935 (National Park Service: Aztec Ruins National Monument files at the National Archives, Washington). | |

|

|

Figure 7.11. Interior of restored Great Kiva, looking toward north altar

room. Crossbedded poles in roof support column left exposed to demonstrate method of construction. |

|

| Figure 7.12. Reconstructed Great Kiva, northwest side. Doorways open into encircling surface rooms. |

The scaffolding scarcely had been removed before the public began asking permission to use the rebuilt chamber for various special functions not related to the monument's purpose. These included such affairs as weddings or association conventions. The largest public gathering in the Great Kiva was an Easter sunrise service in April 1938 for all San Juan County religious organizations. More than 2,400 persons attended. [96] This important interaction between the monument and the community continues.

Administration Building and Third Museum

According to blueprints drawn in November 1933, the vacated five-room Morris house, including the west room the American Museum had intended as an exhibition hall, was to be remodeled into monument offices and a museum under a Public Works Administration project. A lobby of approximately 980 square feet would be built to connect this structure with the comfort station complex to the east erected two years earlier (see Figure 7.13). A 1,305-square-foot museum would be placed on the west side of the old house. A new porch would extend across the front of the lobby, a door from the museum opening on the original porch at the west. [97] As had always been the case at Aztec Ruins, it was the museum which would cause most controversy.

|

| Figure 7.13. Lobby being erected between Morris house and comfort stations, 1934. |

The first phase in the process of getting a satisfactory museum for the monument was an inspection by Carl P. Russell, field naturalist with the Landscape and Education Office in San Francisco. What he saw was the display as it had been arranged by Custodian Boundey of almost 1,500 objects within the seven ruin rooms. [98] Faris did some reorganizing and installed a few glass cases to protect special artifacts. [99] Russell deplored the poor lighting, lack of visual explanatory materials, the necessity for the services of a guide, and rainwater that ran into the east entry to soak floors. He wanted to see a more controlled, up-to-date facility. He further recommended cataloging the undocumented assortment of accrued specimens, especially the American Museum collection, prior to curatorial work. [100]

Although Morris agreed with Russell's appraisal, adding that theft, breakage, and dust were other drawbacks, Custodian Faris remained enthusiastic about the museum within the ruin. [101] He argued that its atmosphere appealed to the viewing public more than what he called a "glass coffin" standard museum. It was an argument he lost.

Proceeding on Russell's report, plans were prepared for the administration and museum building according to the preliminary blueprints of November 1933. [102] A sum of $9,000 was allotted for its construction. On the following July 5, 1934, invitations for bids were sent to six construction firms: one in Aztec, three in Durango, one in Boulder, and one in Los Angeles. No bids were returned. None of the contacted companies felt it could do the job for the sum allocated. The main problem was that the museum as designed was too elaborate for the permissible budget. The museum was eliminated from the final plan. When he returned a bid of $8,400, Harry Gedney, of Durango, was awarded the contract for construction of the remaining building. [103] The foundation and fill for the museum were included. These were dropped, and the amount of the Gedney contract was reduced by $408. [104]

William Gebhardt, assistant architect in the Branch of Plans and Design, Western Division, was in residence at Aztec for four months during the winter of 1934-35 to oversee the erection of a condensed version of the administration building (see Figure 10.1). The Morris living room with its small corner fireplace and front bedroom were converted into a custodian's office. The kitchen was to house a clerk. Even though there was no such position on the Aztec Ruins roster, the large room on the west end of the building was assigned to the naturalist. This part of the combined units of the building still was covered with twelfth-century ceiling elements. The stone masonry of the same age was under plaster. The new spacious lobby (23 by 35 feet) had walls of exposed, carefully laid, stone masonry over a hearting of locally made adobe bricks. A ceiling of large and small peeled beams mirrored the regional style. Doors front and rear permitted a flow of tourists directly through the building.

On the exterior, crenelations were removed from the roof line, and both the new and old sections of the building were plastered to simulate adobe. The stairs to the cellar were aligned so that they paralleled the rear wall of the building. A beamed porch put on this same facade was removed 30 years later because the wood rotted. The added front porch duplicated that on the house in having cedar posts reversed so that spreading roots engaged the roof. A modified Puebloan edifice emerged from all these changes. [105]

Privately, Morris was disgusted that, after all the years of anticipating a formal museum to show to the world the Anasazi material goods he recovered with so much effort and cost, it was abandoned as being something superfluous. "While there was a Public Works allotment for the construction of a formal museum at the Aztec Ruins, what impressed me as an extremely stupid procedure on the part of the Branch of Plans and Designs in sending out specifications for the structure which could not possibly be met with the amount of money available, the museum will not be built at the present time." [106]

Faris was not discouraged; from the beginning, he had opposed the plan for this particular kind of museum. When it was obvious that there was no support for keeping the museum in the ruin, he turned to advocating the use of the Great Kiva for that purpose. He knew that it would make a very favorable, long-lasting impression on visitors. Ansel F. Hall, Field Division of Education, seconded the notion. [107] This was not an entirely original idea. Staff members at the American Museum once had suggested a new museum building along the same plans. "It is hoped that in the near future it will be possible to construct a small building for museum purposes," the report stated. "The building possibly to duplicate the general plan of the structure known as the Great Kiva, one of the large ceremonial chambers excavated. If such a museum building should be provided for by outside support, the American Museum will undoubtedly contribute the plot and building still held in its name." [108]

Use of the reconstructed Great Kiva as a museum was a suggestion Faris submitted with a detailed outline. [109] He proposed to have Chacoan artifacts at floor level around one side of the chamber, Mesa Verdian around the other, thus clearly differentiating the two occupations. The altar room would contain a special exhibit on burials. The other surface rooms would house lesser artifacts or serve as study areas. Technical problems of heating, lighting, flooring, ventilation, security of specimens, and the possibility of detracting from the religious nature of the structure ultimately ruled out his interesting plan.

In January 1935, $3,100 was set aside for museum furniture, nine display cases of different types, and preparation and installation of exhibits. [110] A year later, $1,950 was added to the museum fund. [111] Just where that museum was to be and how it was to be arranged was not decided. That did not mean that Faris, for once, was without ideas. Both he and Park Ranger Robert Hart sent suggested detailed layouts to Pinkley. [112] Their plans were based on experience with the flow of visitor traffic through the site. In their proposals, the new lobby was a staging area, a place where some orientation to the area's physical environment and the prehistoric cultural story was explained. The guided tour then would proceed to the Great Kiva, out across the courtyard, and through the sequence of rooms with ceilings. Despite the fact that moisture was a worsening problem, both men were reluctant to leave these rooms bare. Faris wanted a series of drawings placed there to explain Anasazi cultural evolution from Basketmaker III through Pueblo V and suggested installing some life-sized models of persons at various daily chores. A later project was designed to put one experimental mannequin grouping in place. Apparently, this was not done. [113]

The Faris-Hart tour would continue to the rear T-shaped door on the west end of the administration building to enter the museum room (approximately 12 by 24 feet). There, Faris suggested various aspects of Anasazi life at Aztec Ruins be exemplified. Two windows on the west exposure and a door on the south would be sealed to provide sufficient wall space. The Faris plan for exhibits in this room reflects the tendency of older museums to overload cases with specimens. In Faris's plan, a second smaller room created out of half of the custodian's office would contain further materials, especially a Chaco burial to, as Faris said, "send the visitors off with a thrill. One might think off hand that anything but a burial would be the thing to send him off with a good taste in his mouth, but they like them and we have some mighty dandy examples." [114] The exit from this room would be to the front of the building, after the visitor registered.

Because a door between the west room and his office did not exist, Faris asked Ansel Hall, who was in charge of museum plans for Aztec Ruins, to have one cut. [115] Faris's mistake in not working through proper channels caused problems. To do this small remodeling entailed using money not meant for that purpose. An immediate rebuke from Pinkley canceled the request. [116] Faris left Aztec to become custodian at Canyon de Chelly National Monument without seeing his Aztec museum become a reality.

The Field Division of Education at the Western Museum Laboratory in Berkeley prepared interpretive displays for the museum and supplied cases after a plan drawn by Louis Shellbach. [117] One of these featured tree-ring dating, which just five years earlier had given Aztec Ruins a secure time slot in regional prehistory. Sid Stallings, Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe, plotted a demonstration beam section. [118] Another display was of the small, well-worn hand tools used by Morris, accompanied by his photograph and that of the Anasazi great house he helped expose and preserve. [119] A floor plan showed other cases devoted to Southwestern archeological chronology, stratigraphy, and resources. In the center of the lobby was to be a floor case containing a Mesa Verde burial with accompanying goods. [120]

Although their final placement was not determined, shipments of museum exhibits and equipment were received through the spring of 1935. Faris conceded that visitors seemed to like these displays. [121] In August, a dinner for former Director Horace Albright and 90 local businessmen dedicated the structure. [122]

CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a third Depression-period agency to help improve Aztec Ruins National Monument through an extensive work program. Beginning in April and continuing through September 1935, 15 to 20 young men and three supervisors were transported daily by two trucks from a camp set up at Durango. Working in coordination, the National Park Service branches of Plans and Design and Engineering and the Emergency Civil Works program requested seven specific projects for Aztec Ruins at an estimated total cost, including supervisors' salaries, of $1,660. These were: (1) grade, gravel, and landscape a rear patio behind the administration building, put a foot bridge over the pond there, and install a drinking fountain; (2) remove an old shed still leaning against the ruin and the Morris garage in one of the ruin's rooms; (3) rework old farm fields and replant them with native trees and shrubs; (4) obliterate barrow pits, dumps, and exploration trenches and put debris from them in arroyos in the vicinity; (5) pave bottoms and banks of irrigation ditches to prevent erosion; (6) construct a 175-foot-long adobe wall from three to nine feet high around the residential area; and (7) install cement seats for public use along the patio wall. [123]

Because a permanent park ranger position was added to the Aztec Ruins National Monument staff, a second residence on the monument was needed. [124] Its budgeted cost was $3,900, with $1,500 in addition for a supervisor of the Civilian Conservation Corps crew. Work commenced on the house in November by making adobe bricks. Because the adobes froze and cracked in the winter cold, Pinkley received permission for substitute projects to build sewage tanks, cesspools, and a connecting line, and put a cattleguard at the entrance gate. [125]

Emergency Civil Works employee William H. Hart made an inspection of Aztec Ruins in March 1936. With the exception of the park ranger house, he found all the listed projects completed or nearly so. The proposed residence was not built until 1949. [126] Twenty years later, the surrounding land was incorporated into the Aztec city limits, and livestock were not allowed to roam freely. That made the cattleguard unnecessary. It was removed. [127] In 1961, the pond in the patio, fed periodically by the irrigation ditch running diagonally across the north yard, was a dry depression. It was filled and converted into a patch of lawn. [128]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006