|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 6: THE DECADE OF DISSENTION, 1923-1933

JOINT CUSTODY OF AZTEC RUIN

Since neither the American Museum nor the National Park Service had clear-cut definitions of its future role in the Aztec Ruin and the vague interests of each organization at least theoretically intersected, conflicts arose from muddled administration. The lack of government funding and real interest in the intrinsic importance of the ruin threw a tremendous burden upon the donating institution. When accepting Aztec Ruin on behalf of the National Park Service, Stephen T. Mather, director from 1917 through 1928, stated, "It would be absolutely impossible for us to spend any money on the Aztec Ruin for many years to come, aside perhaps from that of putting in necessary metal warning and fire signs." [1] In the view of the National Park Service, the purpose of creating the monument was nothing more than giving the protection of federal laws to the area. [2] However, if the museum's important investment were not to be lost, it was imperative not only to halt human and natural attrition, but to push forward the research that it hoped would lead to its scholarly understanding. The desire to continue to do these things was there, but the wherewithal was limited and, according to some, no longer the responsibility of the museum.

Nevertheless, although Morris was to be paid by the museum, he also was charged as custodian for protecting government property and furthering government interests. He was to determine ruin repairs necessary to its maintenance and to oversee the work. The cost of laborers' wages and some materials would be met by the government. Minor excavations were to be continued sporadically by a few workmen under Morris's supervision, but the permits to carry on this work now had to come through government channels. [3]

In addition to Morris becoming custodian and Abrams being given a nonpaid semi-official title of U.S. Commissioner, Palmer T. Hudson, a local man who had worked on the excavations, was named park ranger at a token salary of $12.00 per annum. [4] These men legally could apprehend trespassers and turn them over to law enforcement officers. A copy of Rules and Regulations for Use and Management of National Monuments was to be their guidebook (see Appendix H).

One of the aspects of site management not spelled out in the change of ownership from the museum to the government was its visitation by the public. Mather's curt statement upon acceptance gave no formal recognition of this underlying reason for the ruin's conservation except to note that development funds did not exist. It seems to have been assumed that Morris would continue to take visitors through the house block, as he had from the beginning of exploration of Aztec Ruin. Perhaps it was not realized to what extent the tourist traffic would grow. Morris inquired, "Do you wish me to keep as close track as possible of the number of visitors who come here?" [5]

In the decade of the 1920s, the San Juan Basin was a relatively isolated northwest corner of New Mexico. A branch railroad line, the Red Apple Flyer, came down the Animas valley from Durango to the village of Aztec. After much local agitation for it, an undeveloped automobile road paralleled the same route for approximately 35 miles. [6] A rutty dirt track cut across the generally uninhabited uplands of the state from the Rio Grande to Bloomfield and to Farmington and Shiprock. A side road went from Bloomfield north to Aztec to join the continuation of the Durango road along the Animas to Farmington. A similar dirt road ran south from Shiprock through the western sector of the Navajo Reservation to connect at Gallup with the transcontinental U.S. Highway 66 and the Santa Fe Railroad (see Figure 6.1). All these routes across the northern wilderness of the state were subject to being closed in winter by deep snows and in summer by flash floods, slippery mud, or clouds of choking dust. As late as the 1930s, these conditions continued. "Cars are being pulled through sections of the Durango road with tractors, the Cuba road is closed, and our only road is now from Gallup," the custodian at Aztec Ruin wrote. "We walked to town several times this month." [7]

|

|

Figure 6.1. Map of location of Aztec Ruins National Monument and

connecting highways in the Four Corners area. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Despite these drawbacks, from the beginning of the archeological work at Aztec many curious individuals made their way to the well-publicized site (see Figure 3.9). At first, these were local folks, who drove their buggies out in the country to watch friends toiling with residues of the past. Like a proud parent, Morris enjoyed showing off "his" site and explaining what was being learned about its former inhabitants. As automobiles became common after World War I and the urge to travel in them took Americans ever farther from home, the volume of visitation to the ruins increased. Miserable roads notwithstanding, at the end of the first year of the monument's existence more than 7,000 persons had come to the Anasazi great house on the Animas. [8] To prepare for this onslaught of sightseers, Morris hoisted an American flag at one corner of a barbed wire fence across the front yard of the museum property upon which was a sign announcing the hours of visitation (see Figure 6.2). [9] More time was demanded by visitors than could be reasonably expected of an unpaid one-man staff, yet those who made government appropriations did not see fit to provide Aztec Ruin with full-time employees.

|

| Figure 6.2. Morris house serving as monument entrance prior to 1934. |

For most of the first seven months of 1923, Morris was at Aztec Ruin taking on these various tasks, as well as trying to settle down to writing the excavation reports that were beginning to weigh on his conscience. However, that fall, with grants from the American Museum and the University of Colorado, he set out upon a new absorbing excavation program in Canyon del Muerto, Arizona. As it turned out, that research spread over the next four autumns. More important to his commitment at Aztec Ruin was his acceptance of a position with the Carnegie Institution of Washington. That job required him to be in Yucatan, Mexico, for six months a year.

Because his services to the two groups involved at Aztec were entangled, preparations to cope with Morris's withdrawal were equally complicated. The American Museum arranged that Morris be given an annual six-months leave of absence to take the Carnegie Institution position and that he continue to have use of the Aztec house under a 10-year lease upon payment of $1.00 per year. [10] The first leave period was January through June 1924. The museum employed Hudson as caretaker of its property at $50 monthly during this time. [11] Abrams agreed to serve free of charge as the museum's agent in the event the caretaker encountered any problems. [12] Since Hudson already had an appointment as park ranger, he was empowered to act on the government's behalf. [13]

Hudson was to occupy the stone house so that someone always would be at the site. [14] Hudson misunderstood his mission, took on another job, and was gone most of the day. As a result, the National Park Service was upset that visitors could not gain entrance through the locked gate in front of the property, and the American Museum was fearful because its specimen collection had been left unguarded. [15] After Morris completed his second fall season at Canyon del Muerto in 1924, Hudson's appointment was terminated.

The only archeological work at Aztec Ruin during 1924 was small repairs and the excavation of Room 1912. These projects were done during the summer by Owens and Tatman, two helpers from the original crew. The single specimen recovered was a woven headband. [16]

Barely having time to repack his field gear between fall digging in Mummy Cave in Canyon del Muerto and winter rebuilding of the Temple of the Warriors at Chichen Itza in Yucatan, Morris began to realize the hopelessness of his further control of affairs at Aztec Ruin and the evaporating prospects of his completing the ruin's total excavation should the American Museum ever decide to do so. Wissler continued to hold out hope that such a program would happen eventually. In the meantime, he would try to keep the American Museum interest alive. "I will endeavor to bring it about that it will be the Museum's policy to try to tide over by making these modest improvements to the house," he said, "keeping up minor repairs on the ruin, and providing such additional custodianship as may be needed." [17]

With this support, Morris's next choice for a replacement to meet his dual obligations to the American Museum and to the National Park Service to which he personally could not attend was Otha (Oley) O. Owens, a 52-year-old local farmer whom Morris converted into a competent archeological field hand. In the past, Owens looked after the ruin in Morris's absences. As Morris outlined the park ranger job to Owens, "Your duties as ranger will be the guarding of the ruin against vandalism, the keeping of a daily record of the number of visitors, and the sending of a report at the close of each month giving the total to Mr. Frank Pinkley, Sup't. of Southwestern Monuments, Blackwater, Arizona." [18] The National Park Service had begun its management of Aztec Ruin with the prerequisite governmental record keeping. To forestall any repetition of the dereliction of responsibility to the museum which was paying his $75 monthly stipend, Morris also cautioned Owens, "The Museum will expect in return for your salary your presence day and night at the ruin; that is, it is to be as if you were actually living there. If you have to be absent, I would prefer that you leave Oscar Tatman in your place. It is understood that you keep close watch of the Museum's property, and that you will take special pains to guard the building where the specimens are against fire." [19] Morris listed other tasks he wanted done. Most of these related to finishing details on the house. From August through December 1925, the museum expended $1,049.99 at Aztec, of which at least one-third was for completion of the house. [20] Four other projects within the ruin confirmed the museum's intention to continue modest repair and development.

Owens took his new assignment seriously, as is shown in a follow-up letter to Wissler. "I have not been able to do much yet," he explained, "as it came a big snow the next day after Earl left. Then the mercury dropped to 24 below zero. And has been hanging around there ever sence [sic]. And every thing will be looked after in no. 1 shape." [21]

Owens turned out to be a more reliable caretaker than Hudson. The National Park Service had no complaints. Upon his return to Aztec in the summer, Morris reported, "I am well satisfied with Owens's management of things here during my absence. He expended to advantage the residue of last year's Government funds for repair and did some digging in addition." Morris remained frustrated by having to attend to visitors at the ruins when he was back in Aztec. He asked that Owens continue to do this so that he could write. [22]

The digging in 1925 to which Morris referred occurred in two rooms, 192 on the second story of the West Wing and 193 in the North Wing. The first chamber was relatively sterile, so far as artifacts were concerned. A refuse deposit in Room 193 provided 73 specimens, including pottery, sandstone discs, stone implements, bone awls, yucca cordage and strips, yucca sandals, arrow shafts, fiber pot rests, basketry, and wooden objects. [23] From a large assortment of potsherds, Morris restored a mug, a jar, and two canteens. These vessels remain at Aztec Ruins. [24]

Owens once again served as ranger and caretaker of Aztec Ruin during the winter season of 1926. When Morris came back to Aztec that summer, he soon was off on a brief trip to inspect some ancient salt mines in the vicinity of Camp Verde, Arizona, taking Owens with him. In the fall, the two men went back to Canyon del Muerto to continue that exploration. During these absences, at his own expense, Morris employed a single, elderly man, Paul Fassel, a German whom he had met in Yucatan, to share the frame shanty with the archeological collection and the field equipment.

THE BOUNDEY ERA, APRIL 1927-OCTOBER 1929

For three years after the establishment of the monument, the American Museum continued to provide a watchman, who primarily looked after its property but also kept an eye on the ruin. The Trustees decided not to continue offering this service to the government as of January 1, 1927. This move probably was taken to force the government into assuming its rightful responsibility. To that time, only $24 a year actually had been committed to the site's protection, other than $500 for ruin repairs: $12 for a custodian and $12 for a park ranger. Andrieus A. Jones, senator from New Mexico, urged Director Mather to try to get the American Museum to continue its support for a short additional period. Jones planned to pressure the congressional Appropriations Committee to increase its aid to all 32 national monuments. In 1926, that budget totaled just $21,270. [25] During the same interlude, Morris acknowledged a letter from the superintendent of the Southwest Monuments, Frank Pinkley, stating that the government could not provide a custodian until at least the fiscal year beginning in July 1928. Considering his own commitments, Morris decided that meant that for an intolerable interim of a year and nine months there would be no one in residence at Aztec Ruin. Realizing that the National Park Service and its regional Southwest division were actively trying to remedy this situation, he placed the blame on the Bureau of the Budget and the Appropriations Committee of Congress. Even after three days of testimony, the individuals in these groups did not comprehend the destructive problems faced by vulnerable prehistoric entities in the Southwest. [26]

On December 24, 1926, Arno B. Cammerer, then assistant director of the National Park Service, notified George H. Sherwood, acting director of the American Museum of Natural History, that at last Congress had approved a permanent custodian for Aztec Ruin. The same message already had been dispatched to Morris in New Orleans, where he was making preparations to sail to Yucatan for another season for the Carnegie Institution. [27] After three years in limbo, Aztec Ruin was to become a full-fledged part of the federal park system. Events soon showed that this was not to be accomplished without a personnel battle.

In his December telegram, Cammerer asked for advice from Morris about whom to appoint to fill the permanent custodian position. Morris found himself in a quandary. He knew of no one with sufficient intellectual grasp of the archeological significance of the site to, in his opinion, properly interpret it to the public. Owens was the obvious person, other than Morris, with the most intimate association with Aztec Ruin as it had been revealed. Still, Morris felt Owens lacked the knowledge and the managerial skills to be a full-time custodian. Although he apologized for appearing self-serving, Morris suggested that he have the official appointment. He would choose someone else to carry out the immediate routine duties and receive the $100 monthly remuneration until such time as he could give Aztec Ruin his own full attention. [28] In the meantime, Morris was obliged to continue paying Fassel $20 a month out of his own pocket until some definite decision about the ruin's protection was reached.

For the next three months, confusion reigned over the newly created position at Aztec Ruin. Since Fassel already was at the site under an agreement with Morris, he was employed as assistant custodian at an annual stipend limited to $480. Several days later Cammerer again wired Morris in New Orleans that, despite his advice, Owens was chosen as ranger and Fassel was reduced to laborer. Owens was to be paid $1,140 yearly. [29] Probably Pinkley's opinion of Fassel had something to do with the decision not to continue him as assistant custodian. Earlier while the monument staffing matter was before the Appropriations Committee, Pinkley wrote Mather, "Fassel is as honest as the cigar store Indian who used to try to present every casual passer-by with his handful of cigars, and has just about as much brains when it comes to imparting the information the visitor wants concerning the Aztec Ruin." [30] Upon learning of the offer to Owens, Fassel angrily shot off a letter to Pinkley lodging complaints against Owens's aggressiveness in continuing to take visitors through the ruins, although Morris had not authorized him to do so, and generally ignoring Fassel's semi-official status. [31]

The friction between the two men vying for control at Aztec led National Park Service officials to by-pass potential problems by appointing an outsider to the custodian post and rescinding the offer to Owens. [32] They selected George L. Boundey, a career National Park Service man, who had been Pinkley's assistant at Casa Grande National Monument in Arizona. In order to reward his past meritorious service, Boundey's rank was upgraded to custodian at an annual salary of $1,320. Since there could not be two custodians, a brief form letter abruptly informed Morris that his services were terminated without prejudice. [33] He was not thanked for his four years of service without pay, nor was the American Museum of Natural History thanked for its contributions to maintenance of the site until the National Park Service was able to fully take the reins. Not until a month later did Morris receive a letter of explanation of the personnel changes made during the spring. [34] If he felt hurt by this summary treatment, he did not express it in writing.

The townfolks of Aztec always took a keen interest in what was going on at the ruin. They regarded the rejection of Owens in favor of an unknown man from Arizona as a personal affront. Some of them lost little time in protesting to Congressman John Morrow. They complained that Owens was betrayed for political reasons. [35] The reply from Acting Director Arthur E. Demaray that a more experienced man was needed to run the monument and that Owens could be assured of employment in ruin repair did not erase the resentment. [36] Since Morris's exploits in the Southwest and Mexico made him a local celebrity, Aztecans likely included his release among their suspicions of government motives.

Had Morris been in residence at the time of the transition period, the alliance between the National Park Service and the American Museum of Natural History would have been less shaky. As it was, he was anxious that National Park Service employees not exercise unwarranted privileges on museum property he was supposed to protect. Immediately upon learning of his own termination as custodian, he dispatched several telegrams to Fassel cautioning him not to allow that to happen. [37]

When Boundey reported for duty in April 1927, he was not qualified or able to carry out three of the four activities listed in the newly defined custodian job description. [38] He was familiar with the necessary administrative duties, but he was not sufficiently educated about the Anasazi to be an effective guide nor did he understand the demands of the kind of necessary ruin repair. There was neither museum nor specimens, the preparation of which was another of his outlined duties. These facets of the custodian's job at Aztec Ruin caused Boundey difficulties and plunged his administration into turmoil. Eventually, it was his solution to the museum problem and his paranoid behavior arising from imaged wrongs committed by Morris and the American Museum that resulted in his transfer in October 1929 to Tumacacori National Monument, Arizona, where he served as custodian. His administration was the most tumultuous in the recent history of Aztec Ruin. [39]

MUSEUM PROPERTY ADJACENT TO THE MONUMENT

One complication to the establishment of Aztec Ruin National Monument was property adjacent to the monument retained by the American Museum of Natural History. In looking after that holding, Morris was minding his own residence. In 1922, he had been given a long-term lease on the house and associated prehistoric units for utilitarian purposes, with his assumption of upkeep of the water rights, buildings, and taxes. [40] Morris insisted upon the provision that he be allowed to terminate the lease at his discretion. Developing interest in research away from Aztec and uncertainties attendant at that time in the pending transfer of the ruin to some corporate body other than the American Museum might force a move. The use of the house by Morris, the retention of three rooms of the Anasazi structure for personal purposes, and the cistern beneath the house and its outside pump, which provided the only drinking water in the immediate vicinity, caused considerable resentment by National Park Service personnel throughout the first decade of the monument's history.

If the house had been occupied when the Boundeys came, it might have been taken more for granted. Since it was rather special for its day, erroneously believed to have cost as much as five times more than it really had, the house was a daily reminder of a perceived injustice. There it sat, empty, next to the monument, while Boundey was compelled to rent less attractive, less convenient quarters elsewhere. Boundey became so incensed over the house that he made a trip to the county courthouse to check on the lease. That bit of snooping left him flabbergasted at the document's generous terms in favor of Morris. Boundey was unaware of Wissler's sense of indebtedness to his young protege for past and probable future contributions to the American Museum underscoring this deal. The museum felt that Morris's presence and interest in the ruins helped maintain the educational and scientific value of a large financial investment by a prime donor. Moreover, the museum intended to use the residence as a place from which to carry on other studies in the Southwest. [41] In Boundey's warped frame of mind, the lease seemed to represent some unsavory blackmail.

Another irritation Boundey added to his list was that the sole access to the monument was through museum property at the southwest corner of the tract. All other surrounding land was under cultivation or not reachable by road. Both the National Park Service and American Museum pieces of land were fenced to keep out livestock and vandals. Visitors parked in a designated space before the fence in front of the house (see Figure 6.3). They could picnic at a table under a ramada on the terrace between the ruin and its outer revetment. [42] To reach the ruin proper, visitors walked through a gate, circuited what was thought to be an ancient trash dump, crossed the side yard of the house, and went past the Anasazi rooms with modern roofs. Typically, materials and tools used in ruin repair were strewn about (see Figure 4.3). [43] It was not an attractive approach. The museum accepted it as a temporary solution necessitated by the unanticipated fact of its having to regulate visitation. Even after the National Park Service took charge of this part of the operation, existing property boundaries allowed no substantial change to the entrance. Cars parked along the county road, and visitors came to the ruin at its westernmost point but still through the Morris yard.

|

| Figure 6.3. Custodian Johnwill Faris in monument parking lot, ca. 1932. Picnic ramada in background. |

In the summer of 1928 when Morris returned to the battleground that Aztec Ruin had become, he and Boundey suffered heated arguments. Usually a very reserved man, Morris let his anger show in a plea to Wissler to allow him a way out of some of the difficulties. He described Boundey as having a venomous attitude concerning the work that had been done at the site. According to Morris, Boundey was so opposed to the American Museum that he went so far as to accuse the institution of robbery in taking the archeological specimens to New York. The major Boundey grievance, however, was that the museum had not deeded the entire West Ruin to the government. For the sake of peace, Morris offered to pay for removing the tar paper roofs from these rooms if the museum would consider transferring them to the National Park Service. [44] No immediate decision on the gift of this part of the West Ruin to the government was made.

SECOND ENLARGEMENT OF AZTEC RUIN NATIONAL MONUMENT

Before the first tract of Abrams land was proclaimed a national monument, Morris made a survey and suggestions for a second section to include all the prehistoric structures to the east of West Ruin. This was a parcel that was temporarily eliminated in the protracted dealings with Abrams. After an inspection trip in 1925 by H.C. Bumpus, former director of the American Museum of Natural History, Wissler instructed Morris to initiate a plan with Henry Abrams's five heirs for acquisition of this plot.

The second addition took in 12.6 acres and a dozen ruins, the East Ruin being the most prominent. Working through Boyd, the eldest Abrams son who took over the original farm, Morris proposed a one-year option to purchase the tract for $3,500. The money again was to come from the Archer M. Huntington fund. Previous difficulties with encumbrances made both parties distrustful of extras being committed to paper. It was agreed verbally that a natural water course between the West and East ruins was an allowable means of carrying off waste water from the cultivated area to the north. Should waste water ditches be relocated in the future, other provisions would be made for drainage of the Abrams farm. [45] The hay barn to the northeast of East Ruin could be used until money for its removal was obtained. [46] Because negotiations were unsettled before Morris had to depart again for Yucatan, he asked Mrs. H.B. Sammons, of the First National Bank in Farmington, to be the museum's agent in securing the option, having a survey done, and filing the legal documents. [47]

Exactly a year later, in January 1927, the American Museum purchased the second piece of land. The deed was under the scrutiny of the museum's legal advisor. With that transaction, it became the responsibility of Fassel to watch over the property until Morris himself resumed his role at Aztec Ruin in July. Wissler continued to bait Morris with the possibility of future research at Aztec, as he wrote, "What pleases me more is that we have been able to carry out in part, at least, your ideals with respect to the group and to place the ruins in a position where you can at some future time continue their exploration, if that seems advisable. It is of course possible that Mr. Mills [Ogden Mills, New York legislator and later Secretary of the Treasury] may be interested in providing for the exploration of these new ruins in which case I will take the matter up with you before making other arrangements." [48]

The American Museum wanted to add the new tract to the monument as expeditiously as possible. In laying the ground for this second gift to the National Park Service in the name of Huntington, President Osborn contacted Director Mather in March: "On this plot is one major ruin about as large in ground plan as the Aztec Ruin, also three smaller ruins of similar form, and lastly, a unique circular structure [Mound F], well preserved, and promising to be of unusual interest," he explained. "Further our experience in the National Monument leads us to anticipate that a number of older ruins will be found underneath the soil of this new plot." [49]

Just as it appeared that the latest process of increasing the monument size would go through without a hitch, the museum legal staff discovered an error in the deed. It occurred as figures from the original document were transferred to the heirs' deed. Rectifying the mistake took up the fall and winter months of 1927. [50] Then, the gift of the land with the token payment of $1.00 was accepted.

On July 2, 1928, the second Aztec Ruin proclamation was signed by President Calvin Coolidge (see Appendix A). [51] It enlarged the boundaries of the federal holding to incorporate a total of 17.2 acres and 13 ruins and changed its name to Aztec Ruins National Monument (see Figure 5.1). On-the-scene oversight of the second tract passed from Morris, American Museum representative, to Boundey, National Park Service custodian.

THE ARCHEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS AND THEIR EXHIBITION IN THE FIRST TWO MUSEUMS

The goods the Anasazi made for their daily needs were the source of trouble from the time Euro-Americans first entered the Animas valley. They were the lures that prompted many settlers to violate prehistoric sites, unknowingly or carelessly destroying irreplaceable scientific data. They were prizes offered to financiers of shoveling explorations, such as those conducted by Morris himself. At Aztec Ruin, the worn cast-offs, the burial offerings, the objects left by the grinding bins upon departure many centuries ago became a kind of spoils-of-war.

From the initial meeting between landowner Abrams and museum operatives, the division of artifact finds was of uppermost concern. It was commendable for the times that Abrams never thought of a personal collection except in terms of what could be shown to those who took the trouble to come see the old communal house on his farm. A building housing these materials was his primary goal, and none of those who dealt with him over the next nine years of his life doubted it. Still, behind this ideal there probably was a characteristically Western frontier suspicion of Easterners. Abrams likely would not have been surprised if the museum stripped the site, leaving him only a bare-bones, rocky skeleton of what had been.

It is unclear whether, at the conclusion of the exploratory work by the American Museum in 1916, Abrams actually was allowed to select an assortment of small objects taken from the fill of various units. This may have been his stake in exposing old dwellings on his land. It is more probable that the entire haul was shipped to New York. So that there would be no suspicion that the museum was simply out for loot at all costs, Wissler hastened to justify this procedure. "As those specimens have a scientific value," he wrote, "we think it inadvisable to deposit them in the ruin or in the vicinity until proper provisions have been made for their care and housing." [52] For the moment, this was a position to which Abrams acquiesced.

Notwithstanding, at the end of the productive season of 1917, Abrams insisted on earmarking a selection of artifacts for himself prior to allowing the collection to leave the premises. The field catalogue after work stopped indicated 27 specimens as "left with Mr. Abrams" and 65 specimens as "selected by Mr. Abrams." [53] As Morris explained to Wissler, "Most of the specimens would be ready for shipment now were it not for the fact that Abrams insists on going over them, and coming to at least a tentative agreement concerning their division. He is willing then that everything be shipped and remain in the museum several years if necessary for study purposes. I would have preferred not to have taken up this matter at all at this time, but I think Abrams would try to stop shipment unless some understanding were arrived at." [54] Wissler intended to have Abrams come to New York at museum expense and make a division when all the materials were in one place, but Abrams's suspicions made that plan impractical. [55]

About one-third of the artifacts chosen by Abrams came from the rich deposits found in Room 41. Some were outstanding specimens, such as quartzite or onyx knives with wooden hafts still attached, portions of strands of shell or stone beads, mosaic fragments, and especially fine pieces of decorated earthenwares. One of the pieces of pottery was a greyware dipper with black and red decorations. Morris mentioned it in the field catalogue with the notation, "would appreciate the specimen, if at completion of excavation it can be spared from museum exhibit." [56] Morris illustrated 14 of these items in the report upon which he was then working. [57] The artifacts were marked as being for the Abrams collection but were kept in the East. [58] The rationale for this was that analysis for future publication might be carried out there. [59] The war and other circumstances actually shifted most later analysis to whatever quarters Morris occupied during long winters in New Mexico.

During the next several years when negotiations for purchase of the ruins were under way, the question of ownership of specimens became so complicated by alternative proposals that likely neither party to the contract was sure of its current standing. Further divisions of artifacts were postponed. The American Museum felt a sale agreement with Abrams would negate his claim to them. Abrams refused to accept such terms. The museum persisted. Abrams reluctantly gave in.

A museum of sorts was in the offing. Most artifacts, other than skeletal materials and rare items, then were being held at Aztec because they duplicated specimens already in New York, where storage space was at a premium. Wissler considered it pointless to pay intercontinental freight on potsherds or weighty stone objects. [60] A small display, an equitable part of which surely was considered Abrams property although nothing was marked accordingly, was arranged in the storage shed at Aztec Ruin. This showing was to comply with the excavation contract stipulations. Simple as that exhibit was, it was the first museum at the site.

After Wissler came to Aztec in 1919 to discuss a sale, Abrams had a clause inserted into his tentative deed to the property that a formal museum must be established not later than January 1, 1923. Doubtless he was unhappy at the delay in his favorite project and sought to force some action over the next four years. To further secure the rights of the Abrams family and to guarantee a facility available to the town of Aztec, the lawyerly document read: "The exhibit, when installed, shall be open to the public at reasonable hours and seasons of the year, and the grantors and family, and specially invited guests shall have access to the exhibit at such times as the same is customarily open, free of whatever admission charges that may be imposed upon the general public, which charges, if any are made, shall be reasonable at all times." [61]

The museum clause was stricken from the Abrams deed when an American Museum gift of the site to the government seemed feasible. Federal restrictions prohibited its implied future expenditures. Nevertheless, Abrams continued to demand that a museum be included in development plans. To Wissler he wrote, "As to the relics or specimens taken from the ruin under the old contract I am in no hurry for them and wish you to keep them untill [sic] you have made your study of them then I would like to place them in your museum here." [62]

In 1922, the museum to which Abrams referred was the partially finished exhibition room on the west side of the stone house. Meanwhile, after requesting permission to do so on two previous occasions, Morris moved the courtyard shed to the back yard of his house so that there would be no question as to whether the museum or the National Park Service owned the artifacts stored and exhibited in it. [63] In the process, a portion of the flimsy Annex remains was leveled. [64] Earlier a buried kiva was found in the same area while digging a post hole. [65]

The next year when the National Park Service took over, Abrams repeated his familiar message, indirectly acknowledging American Museum, rather than federal, ownership of the artifacts. "Whenever the American Museum of Natural History finishes the exhibit room at the Aztec Ruin I will request them to place therein my part of the relics they have, that have been taken from this ruin, there to remain as a permanent exhibit." [66]

In 1923, one of Wissler's instructions to Morris prior to his first departure for the Carnegie program in Yucatan was to ship all unusual or especially valuable artifacts from Aztec Ruin to New York but to keep at Aztec objects needed for reports scheduled to complete the museum's Aztec volume and an exhibition series to cover obligations to Abrams. He also notified Abrams of these directives. [67]

A year later, the same instructions were repeated, implying that they had not been carried out yet to his satisfaction. Possibly they were intended as a subtle prod to get Morris back to writing about work completed at Aztec Ruin instead of heading for further digging in Canyon del Muerto.

There was a glimmer of hope in 1924 that a museum designed specifically to show Abrams and American Museum artifacts might be constructed. Wissler reported that he was vice-chairman of a new committee formed within the American Association of Museums to work with the "Parks Service" to raise funds for such constructions and their administration within national precincts. Already the committee had obtained money for two museums. Aztec was being considered as the location of a third. [68] An immediate decision about the selection of Aztec Ruin seems to have bogged down. Two years later Bumpus visited Aztec Ruin on behalf of the committee to judge its value as a museum locale. [69] Because two months later Abrams was dead, it is unknown if he was able to confer personally with Bumpus to impress upon him his deep conviction of the necessity for a museum. Very likely he was disillusioned and sure that he had indeed been victimized by Easterners. He no longer had the Aztec Ruin, apparently never had personal custody of any appreciable number of specimens from it, and no museum was in sight.

When the American Museum declined to provide further caretaker service to the National Park Service at the end of 1926, Morris was faced with the problem of security of his own possessions, as well as those in the shed where the first Aztec Ruin museum display was kept. He elected to have Fassel continue to occupy the shed in which he had been ensconced for much of the previous year. Morris moved the display of specimens and boxes of other archeological materials stored there to the greater safety afforded by the basement of his stone house. Morris explained his action to Pinkley, to whom he owed no accounting but whose good will was essential to the successful, albeit unofficial, joint operation of the installation. "I am not willing to be personally responsible for the safety of the specimens housed in a firetrap like the shanty in which they were displayed," he said. "Therefore I have removed and stored the exhibit until the future shall provide decent quarters for it." [70] He also notified Wissler of this move. [71] Both men agreed that under the circumstances storage was the wisest action. The exhibit fell victim to Morris's foreign assignment and to the government's abrogation of responsibility in not manning the monument.

Given the local interest in the welfare of Aztec Ruin, Morris anticipated that there would be a public outcry when the closing of the primitive museum became known. He imagined a clamorous drive for community subscriptions to keep the facility open, but that in the end there would be little money collected and the effort would result in a great deal of abrasive bother. He intended to keep any American Museum artifacts under lock and key until such time as the government demonstrated its sincere interest in providing a suitably monitored museum. [72]

Even with administration backing, Morris remained so worried over possible adverse reaction to his decision by the Abrams family and the community at large that he left a general memorandum in the files detailing his perception of the situation as it then existed at Aztec Ruin. He stated that he anticipated the specimen withdrawal to be a temporary measure. [73]

When Boundey became aware of the situation four months later, he was unsympathetic, apparently preferring to think Morris had acted imperiously rather than cautiously. Probably he was not privy to the agreements between the museum and Abrams about the specimens. His hostile attitude was reinforced when he learned that the splendid painted Room 156 in the West Wing had been resealed shortly after its discovery in 1920 (and has remained so to the present time). Mistakenly, he believed it to be hidden somewhere within the portion of the ruin retained by the American Museum.

In June 1927, Superintendent Pinkley made an inspection trip to Aztec Ruin to see how Custodian Boundey was getting along. He received a barrage of grievances, one of which concerned the Anasazi artifacts. From Crown Point en route back to his office in southern Arizona, Pinkley dispatched a three-page letter to the Washington office recounting these many sore points. [74] The most positive part of the communication was a request that the director attempt to ascertain ownership of the specimens from the site. If the objects did belong to the American Museum, Pinkley asked the director to secure either a donation or a loan of some of them. The reply threw the problem back to the local representatives. "In reference to the ownership of the representative collection of artifacts at the Ruin," it said, "we do not feel inclined to take this matter up at this time, because we feel that you and Mr. Boundey will be able to work out a satisfactory solution of this and other matters with Mr. Morris." [75] In other words, Washington was not interested.

Within two weeks after his return to Aztec from the winter of 1927 in Yucatan, Morris sought and received permission to temporarily loan the government a selection of the archeological materials stored in the basement of the American Museum house. [76] Considering the personal animosity shown by Boundey, the loan was inordinately generous. In November, Morris and Boundey signed an itemized list of some 261 specimens slated to be displayed in a space that Boundey planned to revamp into the second Aztec Ruin museum. [77]

Reflective of the range of artifacts collected from the site, pottery was predominately represented in the loan collection by 139 vessels and a few sherd assortments of both decorated and corrugated styles. Several examples of trade pottery were included, as were two examples that Morris called "archaic." These probably were scavenged from earlier dwellings in the surrounding valley. Of special interest were 11 vessels from Kiva Q and 24 from Kiva R recovered by Morris in 1921 and considered by him to confirm the earlier Chaco occupation. Morris also loaned Boundey manos, metates, grooved axes, chipped knife blades, arrowheads, beads, pendants, quartz crystals, sandals, and one incomplete coiled basket. He likewise offered for exhibit the remains of two children from East Wing rooms, one a burial bundle and the other a skeleton.

Not satisfied with the American Museum loan, Boundey solicited additional contributions from valley residents having assorted "relics." He claimed that more than 500 such articles were turned over to him. [78] Three hundred forty-one specimens received during Boundey's time at Aztec Ruin can be accounted for. Current Aztec museum accession records indicate that a collection of 142 objects was loaned by Sherman Howe on August 25, 1927. In 1928, Mrs. Oren F. Randall, of Aztec, placed 36 specimens at the monument on a 10-year loan. [79] The largest contribution was that by Abrams's widow, Rosa, who loaned 163 specimens in 1928. [80]

Stimulated by Boundey, Mrs. Abrams sought to get returned the specimen collection promised to her late husband. Wissler recognized the legitimacy of her request and expressed regret that so many years had passed without the full analysis of the Anasazi material culture represented by the articles. [81] A search at the American Museum revealed that Morris actually had published on some of the specimens chosen in 1917 for Abrams. This increased the importance of their being held at the museum, as did the necessity of keeping intact some group lots, such as beads making up necklaces. Wissler suggested privately that Morris make suitable substitutions from other assortments of Aztec Ruin artifacts. He added a handwritten note on the margin of his letter to Morris that there was no reason for Mrs. Abrams to know of this action. Wissler had no thought of cheating her, but such a step could be misunderstood by those already antagonistic toward the museum. [82]

When Morris was in New York later that fall, he sorted through the storage cabinets and withdrew 43 catalogue entries for Mrs. Abrams. Thirteen were from the Abrams list of 1917, the remainder being substitutions. None of the artifacts illustrated in the report of 1917 was included. Five examples were from sites other than the West Ruin. Perhaps some of those had been on the Abrams farm but were eradicated. [83] The quality of these selections ranged from excellent to poor, as did those taken from the ruin itself. They included pottery of various decorative styles and forms, bone awls, bone tubes, bone scrapers, fiber pot rests, yucca sandals, a hair brush, fragments of cotton cloth, and one packet of 25 of an original cache of 200 arrowpoints. The number of these specimens seems small when considering that the initial division for Abrams was planned to be about 20 percent of the total. However, they were representative of the full variety of most typical goods and were to go to a site museum that already had 261 specimens and the prospects of hundreds more from those stored at the American Museum field headquarters.

This retrieved collection probably formed part of the much larger assortment of artifacts Mrs. Abrams turned over to Boundey. The bulk of that grouping must have been specimens gathered by her late husband over many years at Aztec Ruin and elsewhere in the Animas valley. More than half of them had no known provenience other than the general vicinity.

Without doubt, the amateur collectors took pride in having their own special possessions on public display. Although there was the danger that it encouraged further illicit digging, the inclusion of their specimens fostered the good will of local people. The specimens exemplified Anasazi mode of life, but their scientific value was diminished by lack of pertinent data about them. Many of the sites within the Animas valley from which they had been taken no longer existed; if they did, circumstances of artifact deposition were not known. Many of those sites in adjacent regions were not sufficiently studied to determine their cultural affiliation. Nowadays, official policy excludes artifacts not recovered on the monument. [84]

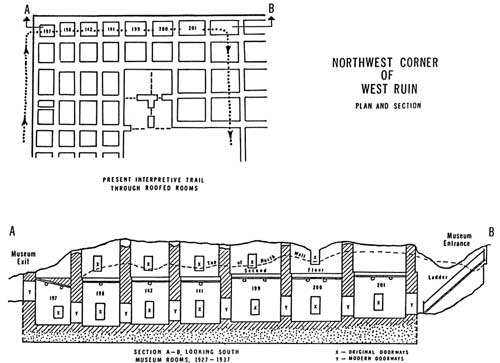

If there were questions about the objects shown in Boundey's museum, there were more about the facility itself. Rooms 197, 198, 141, 142, 199, 200, and 201 on the first floor of the northwest corner of the North Wing of the house block were those originally entered in 1882 by regional schoolboys and their teacher. Room 197 at the west corner was partially exposed by a fallen ceiling. After working down to its floor level, the intruders tunneled horizontally eastward from one room to another, breaking jagged holes in partitioning masonry walls. The Anasazi doorways opened to the south. Each cellular room with original ceiling intact along the northern outer wall was totally dark. There were no windows on the outside wall of the village compound, and small ventilation openings to that exposure were covered with drifted debris. Rooms on the southern flank also were covered. Entrance to the area was by means of a wooden ladder down a mounded area over Room 193. Boundey opened a line of communication from east to west through seven rooms by shaping the irregular settler breaches into doorways (see Figure 6.4). [85] Locked wooden doors were put at each end of this passage (see Figure 6.5). [86] Light from kerosene lanterns provided artificial illumination until the unroofed quarters along the southern side of the museum rooms were cleared in order that natural daylight could pour into the darkened recesses. [87] Electricity was extended to the monument in 1928. A planned wooden plank floor to cover the packed earth original never was laid. Winter visitation was expected to be uncomfortable, consequently brief, since the interior stone chambers retained numbing cold and dampness.

|

|

Figure 6.4. Northwest corner of West Ruin, plan and section. (click on image for larger size) |

|

| Figure 6.5. West exit from roofed rooms of North Wing used from 1927 through 1937 as the second museum at Aztec Ruin. |

Today's standards condemn modern remodeling to create doorways where they had not been prehistorically and in so doing destroy the structure's integrity. In the 1920s, this was regarded as no more outrageous than Morris's adding roofs to some ancient dwellings. It was the removal of debris from the chambers to the south of the line of proposed museum rooms to provide light for the museum to which professionals objected. The cleared rooms later were numbered 239, 147, 144, 126, 205, and 206. Boundey began work in them in December 1927 and continued into the early spring of 1928. [88]

Later, Boundey stated that he carefully drew a plan of each room and indicated on it the exact locations where artifacts were unearthed. [89] No such records have been found. Moreover, Boundey's system for cataloging the 227 recovered specimens was not understood by later researchers. Approximately 135 photographs, which seem to be those of the museum displays but taken outdoors, are unidentified groups of objects on cloth-draped shelves. [90] Lacking close-up views of catalogue numbers on them, it would be a time consuming, maybe fruitless, effort to correlate photographs and objects. Some photographs may have been of ceramics restored in the 1930s. At any rate, it appears likely that Boundey was accused wrongfully of willful pothunting without regard to maintaining proper documentation. His crime was not to provide data in a form recognizable by those who came later. [91]

After reporting on several occasions the work to provide light for the make-do museum, Pinkley received a severely worded directive from Director Mather. Neil Judd, Southwestern archeologist on the staff of the U.S. National Museum and long-time friend of Morris, lodged a strong protest about reputed illegitimate digging at Aztec. Whether Morris had a hand in bringing the problem to public attention is unknown. Mather wrote that activity being done at Aztec Ruin by an untrained person lacking proper authorization would bring criticism of the National Park Service, was to be discontinued immediately, and that the custodian should be instructed to confine his efforts to administration and protection of the monument. Pinkley's unfounded protests that Boundey reclaimed artifacts missed by Morris were ignored. [92] Morris excavated only the second-story units now numbered Rooms 191, 195, and 196, none of those below. [93] The earliest Euro-American entrants on the ground level cleaned out whatever items were visible on the surface. Boundey undertook to finish the job and did recover some overlooked artifacts. [94] Morris had not touched the rooms to their south.

Officials at the Department of the Interior asked Jesse Nusbaum, advisor to the department, to look into what was going on at Aztec. Nusbaum's main complaint was that the excavation was being done without the permit which government authorities saw as a necessary means of curbing vandalism of culturally important resources. By implication, he recommended that work cease at Aztec.

Expectedly, Boundey became defensive. According to him, the Morris house was built to serve as a fireproof museum. Because of Morris's refusal to allow it to be used for that purpose, Boundey was forced into the action he took. He continued, "When I was a boy of twelve I owned 1,000 perfect arrow points and was known as "Arrowhead George." Have been digging for thirty years, have never sold an article for money and everything excavated is in some Public museum." [95]

To soften his own criticism, Nusbaum acknowledged that the editor of the Durango Democrat Herald reported in his newspaper that a recent tour of Aztec Ruin was the most educational of any he had taken in 25 years. [96] That statement probably reflected the feelings of many others. Boundey personally guided each visitor or group of visitors around the ruin, ending the tour by walking through the new museum. Whether his interpretations were correct or current remains questionable. He was not well grounded in Anasazi research. Furthermore, he could not singlehandedly deal with the acceleration of tourist traffic. Volunteers, including Sherman Howe, were called upon to take people through the ruins, while Boundey remained stationed in the museum. [97]

In the museum as it was then set up, the large specimens were placed where they might have been used by the ancient residents. Small objects, such as beads, awls, or arrowpoints, were exhibited in cotton-lined mounts. [98] Many visitors found the hushed, dark atmosphere of the rooms intriguing and likely came away with a heightened appreciation for the architectural skills of the Anasazi. Nonetheless, the open displays and dearth of labels or other descriptive materials meant that the custodian had to be at their elbows to function both as guard and instructor. The lack of protective covering for some kinds of artifactual materials invited possible theft or harm from uncontrolled atmospheric conditions. Their true worth was nullified by scarcity of relevant information.

THE MONUMENT FACES ECONOMIC EXPLOITATION

At first, for some valley farmers wages from day labor at the monument supplemented income derived from cash crops, always at the mercy of fluctuations of weather and markets. Later, a sprinkling of tourist dollars began to flow into cash registers of local hotels and eateries. These economic benefits from a national monument at the edge of town were not expected to greatly increase until improved roads were built connecting Aztec with better known points of interest. Pinkley followed the first staffing of the monument with hopes that anticipated road expansion would be beneficial to several national monuments within his region. "We think we can deflect a line of traffic from Mesa Verde through Durango," he speculated, "past the Aztec and Chaco Canyon national monuments into Gallup instead of letting it go by way of Shiprock." [99] For the time being, however, the existing roads remained a trial in inclement weather, and construction of new links were a long time in coming.

Local organizations remained optimistic. The Aztec Club, an organization of the town's businessmen, ordered 100 signs to point the way to the town and the nearby Anasazi ruins. [100] Not to be outdone, the Women's Club of Aztec paid for erection of a three-pillar arch over the junction of the secondary road to the ruins and the Aztec-Farmington highway to call attention to the attraction of Aztec Ruins. The county highway department helped out by grading the road. In the fall of 1928, a new $100,000 bridge was being put across the Animas River. Indirectly, it would promote travel to the monument. [101]

A hint at the possible effectiveness of the signs, if not improved road conditions, appeared in a brief newspaper article of the period: "Thousands of tourists from all parts of the world visit the Aztec Ruins National Monument every year but this month holds the record with the largest number of visitors for a single month. From the 25th of May to the 25th of June, this year, 1,757 people visited the monument. The visitors represented every state in the Union and several foreign countries including East India, Mexico, Italy, China, Canada, and the Philippine islands." [102]

To take advantage of growing tourism, several individuals expressed interest in opening commercial establishments where they could profit from visitation to the monument. John J. Herring, of Denver, requested permission to operate a curio store on the monument property. Boundey denied this request because of lack of available land and access. [103]

The next month a rumor was making the rounds that one of the Abrams family was planning to lease land across the dirt road along the west side of the monument for a campground and store. [104] The stock market crash and resulting Depression delayed these constructions for a year. In October 1930, the pseudo-Pueblo style building that was to have been an Abrams store fronting on the western boundary road was rented as a residence to the new custodian at Aztec Ruins. [105] The campground in the orchard at one side, which opened that May, began to fill. [106]

AZTEC RUINS NATIONAL MONUMENT GROWS FOR THE THIRD TIME

The remaining parcel of Abrams land the American Museum once intended to acquire in its original purchase was a strip of what was then a cornfield between the major ruin complex and a road running in an easterly direction from the monument entrance along the south property line toward the Animas River. Since there were no extant ruins on this plot, its acquisition was not pursued. With the monument established, this plot allowed more open ground around the prehistoric zone on which administrative necessities, such as a museum-office building and a custodian's house, a more adequate parking area, and an appropriate entrance could be erected. The idea of a National Park Service campground there gained support. However, the government could not purchase the property. The Abrams tentative deed carried the obligation to maintain a lateral irrigation ditch from the 1892 Farmers Ditch, across the museum land, to bring water to seasonal crops generally planted there and to pay its annual assessment fees. [107] Consequently, that little ditch, less than a foot deep and eight to 10 inches wide, and the encumbrances it entailed held up the rounding out of the monument boundaries for a decade.

Preliminary negotiations determined that the Abrams estate would sell Tract 3, as this section was designated, for $1,500. Family members wanted assurance that either they be given a concession to operate tourist-related businesses on the land or that no such enterprise would be allowed there to compete with those they were planning to the west of the monument. [108] There was no formalized agreement on these points, but there was sufficient tacit understanding to satisfy the sellers. [109]

With this Abrams offer in hand and on behalf of the Department of the Interior, Nusbaum approached Madison Grant, of New York City, about buying the desired Tract 3 to contribute it to the government. Grant previously made a smaller gift for purchase of some land in Chaco Canyon. Since that was set aside permanently, Nusbaum suggested that his gift, plus a bit more, be applied to Aztec. [110] Soon afterwards, Grant agreed to put up half of the cost of Tract 3 as his gift to the government. A ruling came down that water ditch maintenance and assessments as appurtenant to land gifts were interpreted as charges for routine services necessary to the monument's operation for the benefit of the American people and that National Park Service representatives were authorized to participate in the affairs of stockholders in a private company, such as the Farmers Ditch Company. [111]

Until the question of the museum property, or Tract 4, was resolved, the National Park Service could not proceed with the monument's full development. It was the long-standing plan of the American Museum to present this holding to the National Park Service whenever that branch of government was in a position to accept it and whenever its own plans for future work in the Southwest, Aztec Ruins in particular, did not require a field station. [112] By 1930, the American Museum decided to withdraw from the Southwest archeological field. With that decision and the federal title to the adjoining Tract 3, that institution forwarded to Horace M. Albright, then director of the National Park Service, the deed to its Tract 4 Aztec property with interest in the Farmers Ditch Company as appurtenance. [113]

An era of scientific accomplishment and public-spirited attitudes on the part of the American Museum of Natural History and one of its foremost supporters, Archer M. Huntington, ended. On December 19, 1930, President Herbert Clark Hoover signed the third proclamation enlarging the Aztec Ruins National Monument by another 8.68 acres, to a size it retained for the next 18 years (see Figure 5.1). [114]

Johnwill Faris, whose father had served in the Southwest for many years as an agent for the Indian Service, became acting and then full custodian from October 1, 1929, through November 1936. Faris came to the job with great energy and enthusiasm and seemingly with more tact and humility than his predecessor. One of his first assignments, which he took on with relish, was to put out old fires. Forthwith, he set about making friends with the Morris family and the citizenry of the town of Aztec. He profusely thanked everyone for past favors and cooperation. After a trip to Folsom, New Mexico, to view the first finds of manmade projectile points associated with extinct bison, Morris wrote Wissler, "I found the new custodian installed here. He seems to be a first class sort with none of the objectionable features of the previous one, and I look forward to most pleasant relations with him." [115]

During his administration, Faris continued to display an effusiveness that caused him to overstep bounds of propriety. One incident of this sort was when he sent the director of the National Park Service and the Secretary of the Department of the Interior paper weights made from chunks of aboriginal beams taken from Aztec Ruins. The officials in Washington politely acknowledged the gifts but soon afterward sent Faris a memorandum concerning the official policy against giving away archeological artifacts from national monuments. [116]

Faris took advertisements in the local papers wishing the community seasons greetings at Christmas time and for several years sent a flurry of Christmas cards bearing a picture of the ruins to visitors who signed the register and to national officers of the National Park Service. [117] Harmony returned to Aztec Ruins.

Faris arrived at a time when the Aztec Ruins National Monument finally was being rounded out to a workable entity and government budgets permitted some basic improvements. Faris proved himself capable of the demanding jobs ahead.

One of the first considerations in the monument's development was the American Museum stone house. Prior to the transfer of Tract 4 to the National Park Service, Superintendent Pinkley and Director Albright wrote to Morris asking if, since the lease he held with the American Museum was due to expire on November 30, 1931, would he be willing to renegotiate a new lease issued by the National Park Service. [118] Providing that the new lease be made for an additional five years, Morris responded that he would accept the change. He was not yet in a position to move away from Aztec. However, should the museum house be desired as part of a headquarters unit, he would give it up in exchange for a new building. He understood one was being planned. [119] Pinkley advised Thomas Vint, chief landscape architect of the National Park Service, of that possibility. [120] After considerable review, the National Park Service decided to let Morris remain where he was for the duration of his lease. That was extended to November 30, 1936, at $1.00 per year. [121]

A month after the American Museum plot was incorporated into Aztec Ruins National Monument, Director Albright recommended to New Mexico Senator Sam G. Bratton a budget of $6,900 to cover cost of the four most needed improvements for the benefit of staff and visitors. [122] With apparent approval, by June 1931 a 73-foot-deep well for drinking water was drilled to replace the cistern, a pumphouse built, two rest rooms served by a septic tank to the east of the house installed, and the first telephone brought the monument in ready contact with the outside world. [123] Rest rooms (or "comfort stations" in the National Park Service terminology of the time) were planned for the west side of the stone house, but to meet objections from Morris, they were put in a small building constructed in the east yard (see Figure 7.2). [124]

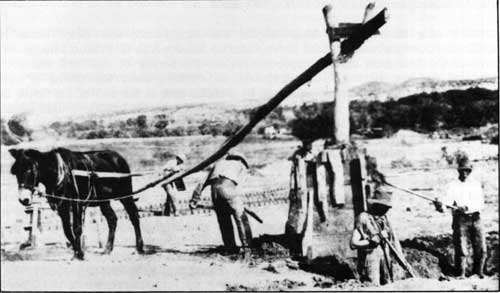

Contracts were let for a custodian's residence and a multipurpose building to be used as a shop, tool shed, and one-car garage. These structures (buildings 2 and 3) faced on to the southern county road at the eastern end of Tract 3 (see Figure 10.5). When completed, the house was three rooms, a bath, and a porch. Its cost was $3,200. Workers mixed adobe for it and the garage in an ageless contraption consisting of a large wooden box in which was a lever attached to an upright pole that was turned by horsepower (see Figure 6.6). Water was dumped into the box. It mixed with earth to emerge at the base of the box at the proper consistency to be poured into brick-shaped molds.

|

| Figure 6.6. Apparatus used to mix adobe mud for sun-dried bricks needed for construction of a custodian's residence, 1931. Bricks drying in the background. |

Faris was pleased with his new quarters, which echoed the Puebloan style popular in New Mexico in the 1930s. "Two foot adobe walls insure permanency and comfort in both winter and summer. Equipped with hot and cold water, automatic water heater, bath and shower bath, fire place, and many built in features, it is indeed a pleasure to occupy such a place," he enthused. [125] Because of destructive physical characteristics inherent in the chosen location, the "permanency" was only 18 years.

An enlarged parking area in front of the stone house and a rearranged entrance accommodated more vehicles and offered a better first impression. The new arrangement provided easy access to rest rooms and a preliminary space for introductory explanatory remarks to visitors. [126]

The custodian granted the unused part of Tract 3 in a short-term lease to a local farmer for a vegetable garden.

One of Faris's crusades was over the deplorable mile-long entry road, which he called a cowpath. It was impassable in the worst of winter and the worst of summer (see Figure 6.7). [127] He failed to persuade the New Mexico Highway Commission to grade and gravel it. He was no more successful in a letter written for the Aztec Chamber of Commerce to the director of the National Park Service asking him to use his influence to have a proposed Park to Park Highway from Mesa Verde to Carlsbad come through Aztec. That surely would force improvements of the secondary monument road. [128]

|

| Figure 6.7. Truck stuck in the dirt entrance road to Aztec Ruins National Monument, 1930s. |

The bad roads could not be blamed for much of the drop in visitation. In 1929, some 18,193 persons were tabulated as having visited Aztec Ruins; in 1932, this number fell to 8,322. [129] The Depression and lack of money for pleasure travel were responsible.

In the area of archeological attractions at Aztec Ruins, Faris left the makeshift museum in the ruin. A wood stove heated two rooms during coldest weather. New locks increasing security were installed after a human skull was taken. [130] In 1931, Morris selected 250 additional specimens from those still stored in his cellar. This required Faris to redo some exhibits. The newly-loaned specimens were things awkward or too heavy for shipment, such as time-stiffened matting, manos, metates, mauls, rubbing stones, or mortars. [131] A seasonal ranger helped guide summer visitors through the ruin. As for himself, Faris was eager to reassure his superiors that he was not straying from his assigned duties as administrator and contracting officer for the new improvements. [132]

When it released its Aztec property, the American Museum requested permission for the specimen collection to remain in storage at least until it was certain that Morris had completed all the reports he was likely to do involving them or until his lease expired at the end of 1931. [133] Wissler suspected that few further papers would be written. Although Morris had left the Carnegie Mexican project, he continued to devote himself to Southwestern studies. [134] Regretfully he told Wissler, "I certainly hope to publish further on the Aztec Ruin, but see no way of doing it within the next few years. To round the thing out properly, I have thought of one paper on general architecture, one on kivas, and a third -- a big one -- on specimens." [135] None of these reports was written.

So much time had elapsed since the artifacts came from the ground and the boxes containing them periodically had been sorted to withdraw specimens to loan to the National Park Service, to return to the Abrams claimants, or to send to New York that the objects and their records were confused. Wissler wanted a full accounting. He felt the entire ruin was not fully represented in the run of specimens housed in the American Museum. Also, he needed a complete record for the National Park Service files. Despite discrepancies in several lists, Morris was confident that all specimens at Aztec could be accounted for, and further, that sending additional examples to New York was not worthwhile. [136] A suggestion that, should the government need the cellar space, the collection be sent to the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe was rejected.

During this period of consideration of the future of the collection, the assistant director of the National Park Service sent a memorandum to his superior in which he made the unequivocal statement that the American Museum would be glad to donate it to the National Park Service. Assurance that it would be properly preserved and exhibited was implicit in this understanding. Nusbaum agreed about the prospects of such a gift from the American Museum to the government. [137] No documentation has been found to confirm that such a gift either was contemplated by the museum or forthcoming.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006