|

Aztec Ruins

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 5: A NATIONAL MONUMENT, STILLBORN

After Nels C. Nelson's recommendation that the American Museum of Natural History undertake excavation of Aztec Ruin, on January 15, 1916, Pliny Earle Goddard, associate curator of anthropology, made the first overtures for the museum's involvement with the site. [1] Three weeks passed before a reply was received from Henry D. Abrams, owner of the farm that encircled the principal prehistoric mound and a dozen lesser ancient dwellings. Although delayed because of deep snow on mountain passes to the northeast, which had held up the mail trains, the response was favorable.

Excavation of Aztec Ruin was something to which Abrams obviously had given much thought. "In the matter of excavating the ruins I may outline an [sic] tentative understanding," he wrote. "Among the things will be the removing of the debra [sic] from the wall on the outside clearing out the rooms and court restoreing [sic] of the walls in minor places strengthening and capping them with cement where required to leave them in a permanent condition, a creditable collection of specimens to remain permanently in such a manner that it cannot be disposed of by any person." In suggesting a three-year project, Abrams generously offered the use of a shaded camp spot, water from his cistern, and assorted fruits from his orchard. [2] He also stipulated that work commence before August 1, 1916. [3] To make it official, he notified Wissler, "I hereby grant to the Department of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, a concession to excavate and study the whole series of prehistoric ruins (known as Aztec Ruins) on my land in northwest New Mexico" (see Appendix C).

On behalf of the museum, Wissler quickly agreed to all these conditions, including clearing down to the original surface, removing debris adjacent to the exterior walls to assure drainage and passage, and compensating Abrams for any damage to crops planted in tillable areas between several mounds of house remains. [4]

About the matter of a specimen collection, Wissler expressed reservations. This was not because of any perceived impropriety in an individual's yen for private acquisition of scientifically valuable public artifacts. It was because of the attitudes of potential donors to the museum's field programs. "When you specify that a representative collection of objects is to be left in your keeping, a great deal depends upon your idea of a representative collection," Wissler cautioned Abrams. "You see it might be very difficult to persuade a donor to contribute several thousand dollars to put another man's ruin in shape and then leave him the collection as well." [5] Nonetheless, in order to secure the deal, the museum agreed that an Abrams collection would be kept at the site or its vicinity for local display and, furthermore, that the project would not be abandoned before the entire village was excavated.

The season of 1917 at Aztec Ruin was so fruitful in artifact returns and in prospects for future research that museum officials began to give serious thought to the permanent conservation of the site. It was an idea that would have a very long gestation period, at the end of which no one would be totally satisfied. One proposal was to persuade Abrams to turn the land over to an established institution or executive board which, in turn, would create a perpetual park incorporating the major and associated satellite remains. In the glow of favorable publicity about the archeological finds being made at the site on the Animas, Wissler felt the museum would have little trouble raising funds for this purpose and in administering the holding. [6] He was not aware of a charter of the museum prohibiting such activity. A second suggestion was that Abrams and several associates form a corporation, with themselves as trustees, to manage this kind of facility. [7] Before any action could be taken on the first option, World War I dried up sponsorship funds for the museum; Abrams, a small-town merchant and farmer, was not sufficiently sophisticated to undertake the second. For the time being, the ruin's future remained in a state of status quo.

Although Abrams had a sincere interest in the ruins, perhaps as much from the celebrity status they provided him locally as from any moral conviction, his primary concern was his farming enterprise. Nor, apparently, was he a man to be rushed into hasty decisions. With detailed instructions in hand concerning the museum's terms for acquisition of the land, Morris and Talbot Hyde conferred with Abrams on several occasions during the summer of 1918 without conclusive results. A flood of proposals and counter proposals ensued.

By 1918, the museum had decided to attempt to purchase approximately 25 acres of the Abrams farm having the densest concentration of Anasazi mounds (see Appendixes D and E). Since the owner was not financially able to donate the ruins to the museum, an outright purchase was necessary. [8] The museum administration made this decision with an eye to future work at a pace slower than had been possible earlier and, at the same time, to protect a previous sizable investment of time and money. The funds to do this were to come from Archer M. Huntington, whose name was not to be used in the negotiations. President Henry Fairfield Osborn remarked that, "the name of Huntington looms large in the West like that of Morgan and Rockefeller," and the price would inflate accordingly. [9] Wissler favored a down payment and two subsequent annual installments. Abrams could retain cultivation privileges for the 10 years but would forfeit all claim to specimens retrieved in the past or in the future. [10]

Providing he could replace them with suitable land at the same figure paid for the ruins, Abrams responded with an offer to sell the 25 acres. He set the sale price for the ruins and encompassing land between $6,000 and $6,500. [11] Since the prevailing price of Animas valley farm land was $300 per acre, Abrams felt that in actuality he would be donating the ruins to the museum and seeking compensation only for the usable land. [12] He would not accept time payments.

Nor, as he made clear in a letter to Wissler, would Abrams give up rights to his artifact collection. "Now as to the relics after having cared for and protected the ruins from destructive `diggers' holding them untill [sic] such a time when just such an institution, as now working them, should take charge of and conduct an [sic] Scientific operation, I feel that I am justly entitled to the few relics that have so far been apportioned to me by your museum." [13] So far as can be determined, Abrams had only a few specimens from the exploratory season of 1916.

Morris stated that the "relics" Abrams had selected but allowed to be shipped to New York for study were among some of the choicest exhumed at the site. Regardless, he felt that Abrams could be persuaded to relinquish them if he could be shown "that without the shadow of a doubt that this archaeological exhibit would be maintained in perpetuity." [14] One of the provisions written into the tentative outline of the sale was that the property would be used solely for scientific and educational purposes and that there be a permanent exhibit of duplicate specimens from the site. [15]

As for the farm itself, Abrams wanted continued use of the tract surrounding the ruins for three to five years and would take care of any upkeep to internal cross fences. He had just planted alfalfa in part of the open land and valued the untillable mounded areas as winter shelter for his stock. At the end of whatever time the museum allotted him, he would remove all pens and sheds from the ruin area except the large hay barn situated to the northeast of the East Ruin. The moving of this structure to another location on his farm would be the museum's responsibility.

Because of the slowness of both parties in coming to an agreement, the museum then asked for and received a five-year extension of its excavation contract with Abrams. This arrangement took its tenure to April 1, 1924. [16]

Meantime, Huntington unexpectedly refused to acquire the property on his own. However, he had no objections to the museum buying it with monies he provided. At that point, the museum lawyers informed Wissler that, even under the guise of a donor name, the institution charter would not permit its permanent retention of real estate. The Trustees added to the dilemma by balking at allowing Abrams to occupy and use the property after its purchase. [17] There, the dealings stalled.

Doubtless frustrated, in the spring of 1919 Wissler asked museum president Osborn for permission to go to Aztec in order to personally present Abrams with four alternatives: (1) the purchase by the American Museum of Natural History of the entire group of antiquities of which the West Ruin was the heart, a tract estimated then at some 23-plus acres, for $6,500; (2) purchase of the West Ruin only; (3) purchase, with a five-year option, of either of the above; or (4) lease either for the purpose of excavation. In the same memorandum, Wissler asked Osborn to approve repair funds for Aztec Ruin because the unusually severe winter had caused many walls to fall. [18]

To Wissler's dismay, Osborn was weary of the seemingly unending troubles associated with Aztec Ruin. "In view of the difficulty of preserving the excavated ruins, and possibly legal questions with reference to the museum's holding such property," Osborn told him, "I do not consider it advisable to purchase the ruins outright." [19] Osborn advocated a long-term lease not to exceed $1,000, with no additional expense after excavation ended. To him, the perpetual preservation of this bit of Anasazi cultural history was not worth the cost.

Notwithstanding this change of heart on the part of the museum's president, Wissler traveled to Aztec during the following summer to put into motion the involved proceedings, which would result in the purchase of only the ruin being dug (see Appendix F). The museum proposed to offer $3,000, contributed by Archer M. Huntington, for the West Ruin and the 6.4 acres of land upon which it sat. The parcel included the area selected for the Morris house. [20] Huntington's reputation had elevated the price. The $3,000 figure did not correlate with the earlier price tag of four times the land for double the amount. Even so, upon learning that Abrams might be considering presenting the property to the state of New Mexico, the museum was anxious that Huntington be recognized as the donor and get philanthropic credit. [21]

To further justify actions contrary to Osborn's wishes as of that May, Wissler claimed that, by owning the land, dirt from the excavation could be dumped where convenient and not have to be hauled away. That would save cartage fees. What were considered "unpromising" parts of the settlement would not have to be dug. The museum no longer would be bound by the agreement of 1916 to expose the entire structure. Perhaps most persuasive of all was the publicity the museum would receive from the growing number of visitors to the ruin. Some 1,200 sightseers had been counted in 1918. [22]

As interest in the acquisition of Aztec Ruin rose, Morris was appointed by the American Museum as its resident agent at an annual salary of $1,200. One of his assignments was to forward the draft of the deed to the West Ruin property and the abstract of title to New York for approval as soon as they were prepared (see Appendix G). [23] With them, Morris enclosed a note saying that, providing a representative collection of specimens was kept at the ruin, Abrams waived all right to "relics." On the condition of a local collection, Abrams was adamant. Although he failed to make it explicit, it seems that he did not intend that the displayed specimens necessarily be from his personal assortment.

The immediate question was what was the museum going to do with a crumbling, large Anasazi community, which had proved impossible to organize and endow as an independent park. Knowing that the museum could act only as an interim landlord while scientific work was under way, activity for which there no longer was financial support, the Trustees would not sanction its acquisition until the matter of final disposition was resolved. There were no legal obstacles to retaining the Morris house and a small plot of adjacent land as a field station until such time as the museum's interest in Southwestern research ceased. [24]

A review indicated that there were three public bodies who might accept as a gift the remaining ruin property and the extensive repairs already made to it. These were the federal government, the state of New Mexico, and the village of Aztec. Wissler leaned toward presenting the West Ruin to the federal government. He learned during several exploratory interviews in Washington that a definite policy was being formulated for the care and enlargement of national parks containing prehistoric ruins. [25] The previous lack of this special attention by the two-year-old National Park Service to antiquities in reserves in the Southwest was the source of much criticism among professional archeologists. Jesse Walter Fewkes, director of the Bureau of American Ethnology, was the only known scientist to lobby the Department of the Interior to accept the ruin as an addition to the national park system. Fewkes's endorsement was met with skepticism by persons outside the government. He was one whose inept, even destructive, work at Mesa Verde National Park had caused much alarm. [26] Moreover, the National Park Service itself did not express interest in having Aztec Ruin in its trust. Arno B. Cammerer, later to become director of the National Park Service, came to Aztec at Morris's invitation, but it is not known that he advised the current director -- Stephen T. Mather -- on its desirability. [27] Neither is there any available documentation to indicate that either New Mexico state officials or the Aztec town council were contacted. In any event, it soon was known that none of the groups considered as possible caretakers would be able to accept the gift under the terms of the tentative deed. Particularly in the case of the federal government, there were stringent laws against any arrangements that called for future expenditures. The stipulation of the Abrams deed mandating construction of a museum did just that. [28] Unless Abrams was willing to trust the government, without a written guarantee, to proceed with the ruin's development and protection as funds were available, the entire transaction was in jeopardy. [29]

Being a capable administrator and not willing to see his plans go awry, Wissler set about oiling the wheels. He wrote Abrams lavishly praising his continued high ideals for the ruin. He noted that a national park would put the town of Aztec on the map in a noteworthy way and pave the way for its future expansion. "I hope to see your other ruins properly excavated and eventually added to this so that ultimately we may have one of the most remarkable National Parks in existence near your town," he continued. [30] He held out a further enticement by assuring Abrams he would be permitted to retain his rights to a duplicate collection. This, Abrams could loan to the government at a later date when space was erected.

The flattery and concessions worked: Abrams reluctantly agreed to sell to the government, with the American Museum as intermediary. [31] The museum retained a 1.8-acre plot of the southwestern corner of the site, including a fraction of the Anasazi house block, as its field headquarters in the event that future excavations were done. An original plan to keep most of the cobblestone South Wing lying west of the Great Kiva was dropped on Morris's suggestion. [32] Four provisions of the deed as finally accepted concerned the right of Abrams to use a road along the west side of the premises and ditch entitlements by both parties to the contract. [33]

As soon as Abrams signed this deed of sale, Morris was instructed to have a lawyer draw a deed of gift from the American Museum of Natural History to the United States of America, with a token payment to the museum of $1.00. It was a bitter pill to swallow, as Morris explained. "Personally I dislike the prospect of seeing the ruin passed over to the United States because of my abhorrence of politically chosen and usually inefficient supervisors, and the labyrinthian red tape which seems to enmesh all government activities." [34]

Other than a plat which Morris prepared, during the following two years no further action was taken for adding adjoining ruins to the museum holding. Morris's drawing indicated four distinct blocks of land that at some future date might be incorporated into the ruin precinct. One encircled the East Ruin and its southern refuse mound. The second was the ruin northeast of Abrams's barn, later named the Earl Morris Ruin. The third was a small circular mound between the East Ruin and West Ruin, later designated Mound F. The fourth block took in a number of minor structures or drifts of ancient debris. Abrams was ready to deed blocks one through three to the museum. He preferred to hold the fourth in escrow for a period of 10 years. [35] It was to be six years before any of these secondary areas were formally set aside.

Meanwhile, the original transfer of 4.6 acres and the West Ruin was moving slowly through institutional channels. An American Museum of Natural History resolution of April 19, 1922, took cognizance of the fact that the government could give no guarantees about the site's maintenance and upkeep. For their part, the Trustees could not promise to provide a custodian but were willing that Morris serve in that capacity when he was in residence. [36] In essence, neither the government nor the American Museum fully accepted the responsibility inherent in the archeological recovery of Aztec Ruin.

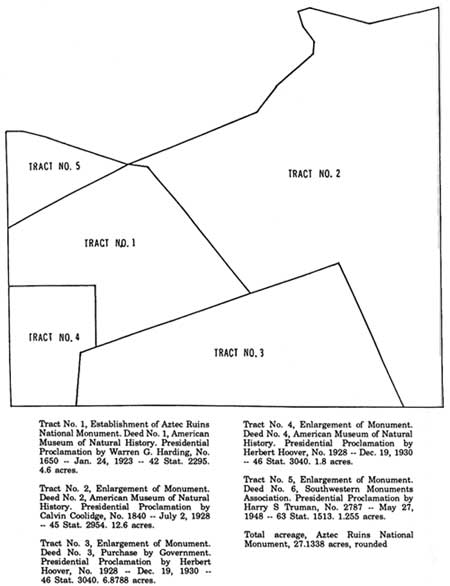

Eventually seven years after the American Museum committed itself to the Aztec Ruin project, the site that its excavator had known since boyhood became the common property of all the citizens of the United States as the 26th national monument, the 14th under National Park Service protection (see Figure 5.1). It was a birth without ceremony. The deed, as it was hammered out over several years, was presented to government officials. Washington staffers drew up a document putting Aztec Ruin in care of the National Park Service by authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906. It was forwarded to the White House for the signature of President Warren G. Harding. Later, Wissler wrote Morris, "We have signed a proclamation establishing the Aztec Ruin National Monument. [37] This is a great satisfaction to us particularly since it marks a definite period in the undertaking. I am also informed that you have been nominated as custodian for the ruin at the magnificent salary of $12.00 per year." [38] Two local newspapers carried confirming reports.[39] The museum unburdened itself, Huntington had the satisfaction of having made a substantial and scientifically significant gift to the American people, and the government in effect regained a patrimony for which it demonstrated little enthusiasm.

|

|

Figure 5.1. Growth of Aztec Ruins National Monument. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

azru/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006