|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 10:

A Different Frontier: Mexico, the United States, And the Dream of an International Park, 1935-1940

Of all the initiatives pursued by the park service in the fateful year of 1935, none had the drama or complexity of the international peace park. Building momentum since the earliest days of park planning, and stimulated by policies in Mexico City and Washington to rethink each nation's relationship to the other, the idea of a joint park along the Rio Grande at Big Bend received its most serious attention in the fall of that year. In so doing, each nation learned a great deal about the conditions of the past that had separated them, while facing the obstacles of economic and ecological devastation that triggered FDR's "New Deal" and Lazaro Cardenas's reform movement. Optimism was in the air as officials at the highest levels explored the means of cooperation, while NPS personnel prepared for inclusion of the international park in the larger domain of Big Bend planning.

While much has been written about the conservation and "Good Neighbor" policies espoused by Franklin Roosevelt, less is known of the work of Cardenas and his advisors on environmental protection. Lane Simonian wrote that "indeed, the exploitation of natural resources has been the dominant theme in Mexican environmental history." He argued that "if the conventional wisdom is true that poor people cannot afford to protect natural resources, then there would be no basis for conservation in Mexico." Yet that is precisely what occurred in the 1930s, when Cardenas asked Miguel Angel de Quevedo to lead a newly created Departemento Forestal, Caza y Pesca (Department of Forestry, Game and Fish). Quevedo, who would work closely with NPS officials in 1935 and 1936 on the joint-park proposal, had studied forest conservation in Paris at the Ecole Polytechnique, receiving in 1889 a degree in civil engineering. His exposure to American conservation programs occurred in 1909, when outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt invited Quevedo to Washington to attend the "International North American Conference on the Conservation of Natural Resources." Consultations with the likes of Gifford Pinchot, Roosevelt's chief of the U.S. Forest Service, helped Quevedo develop an interest, said Simonian, that "lay less with the establishment of a forest industry based upon the principles of sustained yield than it did with the protection of forests because they were biologically indispensable." [1]

Quevedo's journey from the halls of the White House to the Big Bend of the Rio Grande symbolized not only the history of Mexican conservation, but also that of border relations and the twentieth century Mexican political economy. Eager to promote his ideas of forests and parks, Quevedo sought to interest revolutionary leaders like President Venustiano Carranza, who agreed in 1917 to establish outside of Mexico City the first Mexican national park: El Desierto de los Leones (The Desert of the Lions). Five years later, Quevedo had formed the private "Mexican Forest Society," and petitioned President Plutarco Elias Calles "to establish national parks in areas with high biological, scenic . . . and recreational values." Calles did not implement Quevedo's plan, and Simonian summarized Mexico's conservation ethic by the 1930s as "weakened by the disinterest of powerful Mexican officials and by a lack of general public support." [2]

Quevedo's persistence would pay off, and hopes for a true national park system in Mexico would rise, when President Cardenas announced that, in the words of Simonian, "conservation was in the national interests and the irrational exploitation of the land must come to an end." Michael C. Meyer and William L. Sherman, authors of The Course of Mexican History (1995), described Cardenas as "intensely interested in social reform." The Mexican leader also "had that special charismatic quality of evoking passionate enthusiasm among many and strong dislike among some." He inherited a nation that was but 20 percent urban, and where rural "per capita income, infant mortality, and indeed life expectancy lagged behind that of cities." To address these inadequacies, said Simonian, Cardenas's "administration undertook the largest land reform program in Mexican history, extended irrigation projects to small farmers, experimented with alternative 'crops,' such as silkworms and sunflowers (for the oil), created rural industries, and established fishing and forestry cooperatives." Cardenas also approved of Quevedo's efforts to mitigate erosion caused by deforestation of Mexican lands. From 1934 to 1940, Quevedo oversaw the planting of some two million trees in the Valley of Mexico alone, and four million more throughout the republic. This commitment encouraged Quevedo to press for more work, in that "Mexico's forest problem was so complex and so difficult that only a permanent campaign that enlisted the support of the entire citizenry on behalf of forest conservation could succeed." Finally, Quevedo worked with Cardenas to establish some 40 national parks in Mexico, although in the words of Simonian: "Twenty two were less than the size of Hot Springs National Park [in Arkansas], the smallest national park in the United States." [3]

The limitations that Cardenas placed in the summer and fall of 1935 on Quevedo's plans for national parks would hinder negotiations with the United States. "Like their U.S. counterparts," wrote Simonian, "Mexican officials rarely created national parks that incorporated whole ecosystems." Quevedo identified park lands based upon their "scenic beauty, recreational potential, and ecological value." Much like the NPS, the Mexican system of parks would be promoted for their "therapeutic value." Finally, Quevedo "believed that international tourism would further cooperation between Mexico and other countries;" a key feature of FDR's Good Neighbor Policy and his New Deal ventures into natural and cultural resource preservation. This meant an emphasis on park development in and near the population centers of Mexico, especially its capital city. "Quevedo created a national park system," said Simonian, "whose centerpiece was the high coniferous forests of the central plateau." How this concentration of resources and attention far to the south of the Rio Grande would affect negotiations for a joint international park became clear as the two countries planned meetings along the border, and talked at the highest diplomatic levels about a partnership never before attempted. [4]

Given the circuitous journey taken since 1935 to establish an international park in the Big Bend area, the speed with which American and Mexican officials moved that year engendered hope for the future of the partnership. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes had asked Secretary of State Cordell Hull to formulate the diplomatic protocol for planning such an endeavor. Ickes himself envisioned naming the new park (or at least the American side) the "Jane Addams International Peace Park." John Jameson wrote that the Interior secretary saw this as "a fitting memorial to a fellow Chicagoan and the winner of the 1931 Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of her lifelong commitment to international peace and understanding." Addams had brought to the immigrant neighborhoods of late-nineteenth century Chicago the British concept of the "settlement house," where educated reformers (both male and female) would teach middle-class values and American citizenship. Popularized in her book, Twenty Years at Hull House, Addams's outreach programs increasingly included Latinos recruited to the Midwest to replace the European ethnic groups she had first encountered in the 1880s and 1890s. Ickes, who had worked in Progressive-era reform programs in his hometown of Chicago, saw a strong connection between Addams' service to Latinos, the president's initiatives for better relations with Mexico, and the appeal of an international park dedicated to peace in an era of escalating tensions in Europe and the Far East. [5]

Word of Mexico's commitment to the discussions came in late July, as U.S. ambassador Josephus Daniels wrote to Hull that "it is my understanding that the Bureau of Forestry of the Mexican Government has written to the Foreign Office expressing its interest in the project." Daniel Galicia, chief of the Mexican forestry bureau, informed Daniels that "he was sending an expedition into Coahuila and Chihuahua in about three weeks to study the possibility of establishing a corresponding reserve on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande." Galicia had asked the American diplomat "especially for a map showing exactly the areas involved in the American project and any other [particulars] which might be of assistance to him in making plans for a Mexican park." Galicia's superior, Miguel Angel de Quevedo, also asked Daniels to coordinate a meeting with U.S. officials on the initiative. "I found Mr. Quevedo personally most enthusiastic at the idea," said Daniels, with "his chief interest [being] the possibility of making the park a great game reserve." Quevedo mentioned to the U.S. ambassador that "the big game in the northwestern part of the State of Coahuila, some of the finest in the country, is in danger of extinction." Daniels believed that "the Government already owns much of the land in this section and that the President has approved the drafting of a bill for submission to the next Congress authorizing the Forestry Department to issue bonds for the purchase of any additional lands necessary for national parks." Quevedo and Daniels also discussed "the naming of the park," and the former stated that "this was a matter on which [the Mexican] Congress and the authorities of the States concerned would probably wish to be consulted." [6]

To expedite the request of Galicia and Quevedo, American and Mexican officials met in El Paso on October 5 to plan for a larger conference in that border city the following month. There Herbert Maier learned from Galicia and from Armando Santacruz, Junior, Mexico's commissioner to the International Boundary Commission, of that nation's interest in water projects along the Rio Grande. Maier quickly corresponded after the meeting with L.R. Fiock, regional director of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), about Santacruz's suggestion "that it is the plan [of the IBC] to erect three dams along the Rio Grande in the Big Bend area;" one each at the mouths of Santa Elena, Mariscal, and Boquillas Canyons. "From what he said," reported Maier, "I gathered that the U.S. Federal Government tentatively favors the erection of these dams." Maier recalled that upon his most recent visit to the Big Bend, he had heard of "the possibility of such dam promotion." This he had dismissed because, "as you know, dams have been proposed for about every strategic point on about every river in the United States during the past decade." The NPS officials told Fiock that "even if the Mexican government favors such a move, I am sure that it will be out the line of normal policy to approve of our participation in these hydraulic ventures because . . . our national park areas are to be maintained in their wilderness state." Maier decided not to engage Santacruz in a discussion of NPS policy "because I did not wish to complicate the picture." He informed the USBR official that "it has been tentatively proposed that the area on the Mexican side be set aside as a large Forest and Game Preserve." He knew that the Rio Grande's international status meant that "such hydraulic ventures would have to be anticipated." Yet the United States, "on the basis of its future adoption of the area as a national park, can withhold participation in such ventures if that appears advisable." As Fiock had replaced the current U.S. commissioner to the IBC, L.M. Lawson, Maier asked that Fiock supply him "with information as to what extent the U.S. Reclamation Service is seriously considering the erection of dams at these three canyons." He also asked that Fiock "hold the matter of my inquiry confidential," as Maier knew that the NPS's Washington office would handle all conversations with Mexican officials on this matter. [7]

Issues of water quality and quantity would affect management of Big Bend National Park from its inception. Thus Fiock's response to Maier's confidential inquiry revealed how each nation would envision water resource planning in the Big Bend area. Fiock claimed that he possessed only "meager knowledge" of the "proposed construction of dams on the Rio Grande below El Paso." He had not worked on the surveys for water projects between that city and the Gulf of Mexico, but did have access to informal details within the USBR. "In 1919," Fiock recalled, "the Bureau of Reclamation through some cooperative arrangements with the Irrigation Districts of the Lower Rio Grande Valley (Brownsville section) made a preliminary investigation of possible storage reservoir sites." He also knew that "being an International proposition the International Boundary Commission, . . . [had] interested themselves during the past several years in these matters." This led Fiock to believe that the IBC was "working cooperatively on plans, at least to the extent of collecting necessary essential data." The USBR official had visited the three canyons of the future park, and considered them "exceedingly favorable for dam construction." He cautioned Maier that "it seems doubtful that there is a sufficient discharge of water in the Rio Grande at these points to fill the reservoir which could be created by either one of them." Fiock reminded Maier that "the flow of the Upper Rio Grande is entirely controlled by Elephant Butte Dam and Reservoir," north of Las Cruces, "and there are no large tributaries to the Rio Grande between Elephant Butte and the Pecos River," below the proposed national park. In Mexico the only stream flowing into the Rio Grande in the vicinity was the Rio Conchos, and "there is already constructed on the Conchos River a dam and reservoir almost identical in proportions with Elephant Butte [itself a storage basin of two million acre-feet of water]." [8]

Besides the lack of water quantity in the Rio Grande through the Big Bend, Fiock also noted the use of irrigation far from the park. "Construction of dams in the canyons of the Big Bend," said the USBR official, "can not provide major flood control to the lower Rio Grande Valley because of the tributaries which produce high runoff which causes the destructive floods entering the Rio Grande below the dam sites." Even if "international relations permit and funds [are] made available," said Fiock, "the first dams to be constructed will be as far down the Rio Grande as possible and still be above the Lower Rio Grande Valley." The USBR knew of two such sites: "the Salineno site for a dam and regulating reservoir and the El Jardine site for storage and flood control." Then Fiock suggested that "there are no favorable sites between the El Jardine site and the canyons of the Big Bend." This meant that "possibly the Boquillas site or one even below that would be chosen if it is at all possible to find a satisfactory site on farther down the river." He then hinted that "apparently the only reason there would be for consideration of the construction of more than one dam in the canyons of the Big Bend would be for the purpose of power development." Yet "the isolation of the territory from any large power market even if there was river discharge enough to generate any appreciable quantity of power," said Fiock, meant that "the chances of development of power possibilities are very remote indeed." Should that be the case, "dams could be constructed at each successive site which would back water to the dam next above and so on down the river through the entire canyon section of the Big Bend." [9]

Fiock's ambivalent stance on water projects in the Big Bend canyons led Maier to correspond with his superior in Washington, Conrad Wirth, about inclusion of this topic in the upcoming meetings with Mexican officials. Even though Maier had confidence that the Interior department could block such projects, he told Wirth that "I want to have first-hand information as to just what the U.S. Reclamation Service and the International Boundary Commission down there really have had in mind." Thus Maier had initiated his contact with the El Paso office of the USBR. "This had taken a little time," he told Wirth in explaining the lateness of his report on the October 5 meeting in El Paso with Mexican representatives. It also "has had to be handled carefully," Maier noted, "because we do not wish to 'scare' the Mexican officials away from the park idea." [10]

Soon thereafter, L.M. Lawson of the IBC contacted Maier to offer his thoughts on the Big Bend dam issue. Lawson's organization "[had] for some time been engaged in a study regarding the equitable uses of the waters of the Lower Rio Grande," said the U.S. commissioner, "and [had] been active in the measurement of discharges of the main Rio Grande and tributaries." In recent years "extremely large flood flows and serious water shortages" throughout the length of the Rio Grande had raised "the question of flood control and conservation of water." In August 1935, President Roosevelt had signed legislation that gave the IBC authority to conduct technical and other investigations relating to flood control, water resources, conservation, and utilization of water, sanitation and prevention of pollution, channel rectification, and stabilization and other related matters upon the international boundary. This had granted the IBC its access to the Big Bend area, though Lawson echoed the thoughts of the USBR when he told Maier: "The use of water, both in the United States and Mexico, above the Presidio Valley, which is the beginning of the Big Bend district, results in very little accumulation to the river from the upper Rio Grande." Records kept by the IBC "would indicate that about seventy percent of the Lower Rio Grande flow come from Mexican tributaries, with the remaining percentage from the Devils and Pecos Rivers of Texas." [11]

Lawson then advised Maier that "while some flood control works are now being construction by the Commission on the Lower Rio Grande, "others are planned in and below the Big Bend district." His agency had studied "a number of damsites . . . with the view of developing storage and hydroelectric power." Mexico and the United States, Lawson conceded, "have not yet come to final agreement upon the equitable distribution of the international waters." The IBC commissioner also admitted: "Nor have final plans reached any definite form as to which storage site in the Big Bend district would be the most feasible and economical." Lawson assured Maier that "this decision . . . rests upon the joint determination of the undertaking." He then closed with the vague statement that "it can be assumed that at some future date plans will be carried out to some finality in taking advantage of the storage possibilities that exist between the canyon section of the Rio Grande in the Big Bend district." [12]

While planning for water projects worried Herbert Maier, he also had to oversee the details of the first major gathering in the twentieth century of Mexican and U.S. officials on border issues. Less than two decades after the "raids" by Pancho Villa and the resultant Pershing expedition into Mexico, American and Mexican scientists, park officials, and diplomats agreed to assemble in El Paso. Even before this meeting on November 24, 1935, Maier coordinate a visit to Arizona by Daniel Galicia, Maynard Johnson, and Walter McDougall to accompany a U.S. Biological Survey party in the "King and Houserock Valley Refugees areas in Arizona." Their goal was consideration of the plans for the "Ajo Mountain National Monument," later to become Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Galicia noted that this desert plant extended from southwestern Arizona to the Gulf of California. This shared ecosystem prompted calls for an international park on the Arizona-Mexico border similar to Big Bend. Maier suggested to Conrad Wirth that this surge of interest by Mexican officials might be enhanced not only by the El Paso meeting, but also by extension of invitations to Miguel Angel de Quevedo and other Mexican park officials to travel to Washington in January 1936 to attend the annual NPS superintendents' conference. "It occurs to me," wrote Maier, "that, after all, the final conference on the birth of the International Park should be considered rather an historic event." In conjunction with the anticipated agreement between Mexico and the United States, Maier encouraged Wirth to extend the hand of friendship to the NPS's future partners at Big Bend. "This will not only impress them with the importance of what they are entering into," said Maier, "but should go a long ways towards assuring the success of the undertaking." In turn, the presence of Mexican park planners would "make a favorable impression on the National Park Superintendents and others attending this conference." Quevedo, Galicia, and their associates would thus represent the future of U.S.-Mexican border relations in ways that no one could have anticipated even a decade earlier. [13]

Pursuant to this meeting, and the prior engagement in El Paso, Maier asked Johnson and McDougall for their thoughts on the boundaries for a Mexican park opposite Big Bend. The surveyors disappointed Maier, in that they had not traveled into the Mexican interior. In addition, said Johnson and McDougall, "we know of no one who has made a sufficient investigation of it to attempt a location of boundaries." CCC superintendent Morgan did inform Maier that on July 4, he had entertained a "Dr. Francisco Del Rio," who represented the governors of Coahuila and Chihuahua. Del Rio reported that the Mexican Government is interested and would establish a park of such an area as would be in keeping with the one established in the Big Bend. Morgan noted that Del Rio spent one day in the area, "but was not sufficiently familiar with it to make definite boundary recommendations." Johnson and McDougall did know that Daniel Galicia "is to go into the region for a preliminary survey and then to return later with a party of engineers and surveyors for a more thorough investigation. Galicia had indicated to them that he would make this trip after his survey of the international park at Ajo Mountain. For his part, the chief forester for the Republic of Mexico wrote to Maier on November 12 to indicate his support for collaboration with the United States. "I wish you'd know how glad I'm with it," said Galicia, "because we've found a probability to [e]stablish a[n] Inter-National Park in Punta Penasco, Sonora State, and game refuge along the border." He planned after the first of the year to visit the Boquillas area. "It would be very convenient for you and Mr. de Quevedo to [discuss] the matter over, on his [upcoming] visit to El Paso." Galicia then thanked Maier for sending him booklets on NPS units in the region, and promised to devote time to discussing Big Bend and Punta Penasco at the El Paso conference. [14]

As the international park meeting neared, NPS officials in Washington asked Mexican officials to visit other sites in the United States to observe how the park service did business. Arthur E. Demaray, acting NPS director, wrote to Juan Zinser, chief of the game division of the Departemento Forestal y Caza y Pesca, when he learned that Zinser had decided to travel to California after leaving the El Paso conference. "I hope very much," said Demaray, "that you will be able to visit some of our national parks on the way." This gesture emanated from "the recent resolutions of the Second General Assembly of the Pan American Institute of Geography and History urging park systems for other American countries." Demaray recommended the Grand Canyon "and some of the national monuments established to give protection to historic areas of great interest." In California, Zinser should see Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks. Then he should travel to San Francisco, where "you will find a group of [NPS] engineers and landscape architects who are fully conversant with park policy and operation." Finally, Demaray suggested contacting the California fish and game commission, "the State organization with which Mexico has long cooperated in connection with fisheries off the coast of lower California." The acting director described "this outstanding conservation organization" as "typical of the machinery utilized by the states in enforcing regulations concerning fish and game in conserving natural resources." This effort by the NPS was well-received by Zinser, whom Lane Simonian identified as the member of Quevedo's staff who "established wildlife refuges, signed a migratory bird treaty with the United States, and fostered the establishment of hunting groups" in northern Mexico. [15]

When the historic day arrived, NPS and Mexican park officials demonstrated an eagerness for cooperation and partnership that overrode any concerns held by Herbert Maier about the details of an international park. Among the attendees from Mexico were Miguel Angel de Quevedo, Daniel Galicia, Juan Zinser, Jose H. Serrano and Juan Thacker of Quevedo's staff, and Armando Santacruz, Junior, of the IBC. Other Mexican representatives came from the states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Sonora (the latter to discuss the Ajo Mountain park proposal). American officials included Maier, Frank Pinkley of the Southwestern National Monuments, Vincent Vandiver, regional geologist for the park service, Don A. Gilchrist, director of Region Three of the U.S. Biological Survey, and Charles E. Gillham, game management agent for the biological survey. Maier reported to Conrad Wirth that "the primary purpose of the conference was to afford the Mexican representatives an opportunity for an official indication as to the extent of their participation in national park, monument, and wildlife undertakings immediately along the International Boundary." In so doing, "there was compiled a set of eight resolutions outlining preliminary policy covering the creation and administration of such areas along and extending over into both sides of the boundary." [16]

First among the resolutions was the statement that "the Mexican Government accepts the suggestion of the United States Government for the creation of International Parks designed to include adjacent areas of outstanding scenic beauty on both sides of the International Boundary." From this would come "fostering of a closer understanding between the peoples of the two nations and inaugurating a joint effort for the conservation of natural resources." They saw as critical "the conservation of plants, animals and birds and of all such natural conditions." Each park unit "will be controlled by the proper Department of each Government, subject to joint Regulations to be agreed upon for the maintenance and conservation of the areas involved." Wildlife refuges would be an important feature of international park planning, with "regulations . . . to properly provide for the crossing of the Border by administrative forces as well as the wild life," while "peculiar and beautiful vegetation and outstanding geological phenomena" merited their own "National Reservations." Reflecting Quevedo's concerns for ecological zones shared by border towns, the conference resolved that "with a view to improving the esthetic and health conditions as well as for recreational value to the present communities along the Border[,] it is recommended that the two Governments cooperate in establishing forest plantations around these communities in both Countries." Finally, the attendees declared the need to make permanent the partnership forged in El Paso that day, with a "Joint Commission" created "to carry out at an early date the necessary investigations and surveys for the location of the areas to be included in the proposed International Parks, wild life Refuges, plant Reserves and forest plantations." They then called for another meeting in the Texas border city no later than January 15, 1936, with submission of their findings and recommendations to the leaders of their respective nations some 60 days thereafter. [17]

Herbert Maier analyzed the tone and mood of this conference, and found much to commend. The NPS already had studied the American portion of suggested international park units at Big Bend, the "Espuelos Mountains" of Mexico and the "Hatchet Mountains and Animas-Pelonicello areas" of southwestern New Mexico and southeastern Arizona, and the proposed Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (including the "Rocky Point Area [Bahia Adair]" of Mexico). The latter site had garnered the support of Mexican park officials, who envisioned "a recreational area for fishing and bathing" that would be "accessible from the International-Pacific Highway leading from Mexico City and Guadalajara up the coast to Southern California." [18]

For Maier and his colleagues, the "only international park in which the National Park Service is, or is likely to be, interested in along the Boundary is the Big Bend." Maier liked the suggestion of Quevedo for tree plantations at border communities; something that the forest, fish and game chief had observed in his drive with NPS officials from Laredo to El Paso. Maier praised Quevedo for his "early outstanding record in the reforestation of land surrounding [Mexico City]," and agreed that "such undertakings will be highly worthy and could probably be carried out on our side under the extended CCC program." SWNM superintendent Frank Pinkley noted that each nation need not be bound by the designation given to an area, such as a wildlife refuge adjoining a national park, as "desirable ranges of scenery, fauna or flora, [should] be units rather than limited as at present to an arbitrary line." [19]

The NPS's Maier then offered his assessment of the mood of the attendees, describing that of the Mexican representatives as "earnest and enthusiastic." "Senor de Quevedo," said Maier, "although seventy, is a very energetic individual." Reiterating details of Quevedo's meeting in Washington in 1909 with Theodore Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, Maier noted that he also "is an honorary member of the Society of American Foresters." Quevedo informed Maier of "the legislation he now has in process of formation which will enable his Department to regulate and practically prohibit hunting along the entire Mexican-U.S. Boundary within a zone 150 kilometers [90 miles] south of the international line," a measure that Quevedo assured Maier "has already received the approval of Pres. Cardenas and the Cabinet." Maier then advised Quevedo on his itinerary of western U.S. parks, hoping that he could see the Grand Canyon because of "a similar area in the State of Chihuahua which is also a mile in depth and which the Mexican government has under consideration as a national park [Copper Canyon in the Rio Conchos basin]." Quevedo did not have time to travel to Arizona, but "being primarily a forester," said Maier, "he desired above everything else to see the Sequoia." [20]

Most critical, however, were Quevedo's thoughts on Big Bend National Park. "The Mexican Government," Maier learned from Quevedo, "is prepared to prohibit all hunting on the Mexican side of the Big Bend at an early date." Quevedo also hoped that "the boundaries of the Mexican area shall be based upon biological as well as scenic considerations." While "the bulk of the land is in private ownership (large ranch holdings)," said Maier, "Quevedo stated definitely that he favors the undertaking of a program of land acquisition covering all lands within the boundaries to be proposed." Maier and Quevedo agreed that "this, of course, will be a long term program." The American land-purchase program "will no doubt require several years for acquisition by the State of Texas," wrote Maier, "and just how rapid land acquisition by the Mexican Department will be, it is impossible now to [gauge]." Maier contended that "it is natural to assume that land acquisition may be more difficult for the Mexicans to effect than with us." Yet he saw hope in the suggestion by Daniel Galicia for "acquisition by exchange." [21]

With an eye towards accelerating the process of park planning, Maier suggested to his superiors in Washington that they select a small group to be assembled in Alpine on January 15 to spend some 30 days in the field. The Mexican government had named nine individuals to collaborate with the NPS, but Maier feared that "there is already danger of the party becoming unwieldy." He also noted that beyond Big Bend and Organ Pipe, "the remainder [of the suggested sites] are low in scenic and recreational values from a national park standpoint and should, perhaps, be set aside primarily for the conservation of their peculiar fauna and flora." The U.S. Biological Survey could survey these areas in more detail, leaving the NPS-Mexico team to examine Big Bend and Organ Pipe. [22]

Policymakers in both the NPS and the Departemento Forestal, Caza y Pesca had much reason to celebrate in the first weeks of 1936, as the American secretary of state, Cordell Hull, announced on February 8 his appointments to the United States Commission on International Parks. The list sounded like a "who's who" of natural resource agencies: Conrad Wirth, Roger Toll, Frank Pinkley, George M. Wright, and Herbert Maier of the park service; Laurence M. Lawson of the IBC; and Ira H. Gabrielson of the forest service (replaced a week later by Dr. W.B. Bell). U.S. Representative Ewing Thomason anticipated the importance of this delegation's visit to Alpine in mid-February, and telegraphed Everett Townsend with the news of their impending arrival. "[I] am sure you and other citizens of Alpine appreciate [the] great importance [of] this visit," wired the El Paso congressman, "and what it means toward helping put over our program." Thomason made it clear to the "father of Big Bend" that "I am leaving nothing undone here [Washington] to get results and am sure you are doing same there." In particular, wrote the congressman, Townsend needed to know that Wirth "is our friend," and that "if Mexican authorities are strong for it [the international park] I will co-operate [sic]." Among Thomason's plans were "ideas for getting some money." He then admonished the former Brewster County sheriff: "This is big stuff and we must put it over." [23]

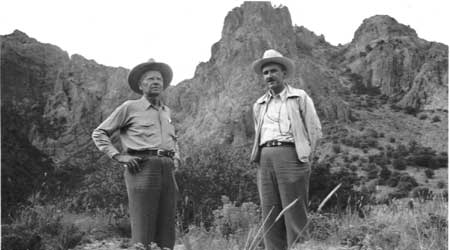

No one had to remind Townsend of the gravity of the moment, as the U.S. delegation stepped from the platform of the Alpine train station on February 17 and shook hands with the longtime park promoter. They and the Mexican commission members, among them such staunch advocates of international cooperation in natural resource conservation as Miguel Angel de Quevedo and Daniel Galicia, drove southward to the future national park and thence to the Rio Grande. Crossing the river at Boquillas, the commissioners drove into the Fronteriza Mountains before exchanging their vehicles for horses. After some time in the area that one day would become the Maderas del Carmen Flora and Fauna Protected Area in Coahuila, the party resumed their automotive tour to what future park superintendent Ross Maxwell would call "several interesting native villages." Then the US and Mexican commissioners drove from Boquillas westward around the north face of the Chisos Mountains to the border town of Lajitas, fording the Rio Grande once more for the trip south into the state of Chihuahua to the historic community of San Carlos (the largest town in what would become in 1994 the Canon de Santa Elena Flora and Fauna Protected Area). [24]

As the commissioners left the Big Bend area, they carried with them the radical idea of breaking with tradition to join the United States and Mexico in creation of an international park where Mexican bandidos and American soldiers had clashed less than two decades before. Photographs of the commission's tour of the Coahuila and Chihuahua landscape published in the Fort Worth Star-Telegram revealed the sense of brotherhood and commitment shared by commission members. The historian John Jameson wrote that the officials marveled at the differences across the river in Mexico, where "unlike the overgrazed American side, there was little evidence of erosion in Mexico, and the mountains were covered with virgin stands of pine trees, some as tall as sixty feet and three feet around the base." Then one of the most tragic events to strike Big Bend (not to mention the international park idea) occurred less than 24 hours after the commission dispersed: the deaths of Roger Toll and George Wright in an auto accident. The two park service officials were en route from Big Bend to study the Arizona border park sites when a car veered into their lane on the old two-lane highway east of Deming, New Mexico. Richard Sellars, writing with the hindsight of six decades of history, would note in 1998 of the untimely deaths of Toll and Wright: "Although not fully apparent at the time, the loss of Wright's impressive leadership skills marked the beginning of the decline of [park service] science programs." It would be 60 years before the NPS and the government of Mexico would hold similar conversations at the highest levels about joining their two nations along the Rio Grande, and by then the memory of Toll and Wright's contributions would have faded considerably. [25]

At the time, however, NPS officials and their Mexican counterparts expressed a determination to continue planning for the international park, using the deaths of Toll and Wright as an incentive. Nonetheless, the initiative had lost two of its most ardent advocates, a circumstance that all who wished for a joint park realized within days. Herbert Maier wrote to Juan Thacker, one of the Mexican commissioners from El Paso, on March 8 to review the planning to date. Maier reminded Thacker that "upon my last visit in your office I had a conference with a man from Chihuahua who is interested in securing a nucleus herd of buffalo and elk for a club in the vicinity of Chihuahua in Mexico." The regional director of the ECW program had discussed the idea with Toll and Wright while on the inspection tour of the international park, and told Thacker: "Both of these gentlemen assured me that it will be possible to secure both elk and buffalo from the Yellowstone herds. [where Toll was superintendent]." Toll and Wright did caution Maier: "It will be highly advisable to consider the matter of undertaking the developing of herds of these species with a great deal of care and forethought." They knew that "in many cases living specimens supplied by wildlife refuge officials have proven a liability rather than an asset, . . . since the undertaking of development of herds involves a great many scientific and practical considerations." Toll advised Maier that "the elk and buffalo indicated for distribution during the current year have all been pledged." Yet the Yellowstone superintendent believed that "it will be quite possible to secure specimens during the coming year." Then Maier revealed to Thacker the scale of the deaths of Toll and Wright to the park service: "Considering the fact that both of these fine men have been unfortunately removed from our midst, I suggest that the individual in charge of this undertaking, . . . take up the matter directly with Mr. Ben Thompson, . . . who is a wildlife expert, and who was assistant to Mr. George Wright." [26]

The death of Toll and Wright also had personal implications for park service officials engaged in the work of park planning in Texas and Mexico. Amidst the correspondence that Leo McClatchy handled that spring was a note from Mrs. Roger Toll, who resided in Denver while her husband traveled the West in search of new parks for the United States. Toll's widow noted that the El Paso Times had printed pictures of the international park survey, and wondered if McClatchy would provide her with copies of the images that included her husband. The NPS publicist could not locate any of the original pictures, as all of the negatives had been sent to the NPS headquarters in Washington. He did, however, have a clipping from the Star-Telegram where "Mr. Toll is seen helping to push the car out of a rut." Then in a touching statement about the meaning of Toll's work to his peers within the NPS, McClatchy told his widow: "Though I had known Mr. Toll but a brief time, he was extremely courteous and helpful to me on the Big Bend trip, going out of his way to assist me in gathering information." [27]

Officials of the department of forestry, fish and game in Mexico sustained their own investment in the international park concept throughout the spring and summer of 1936, with the key representative, Daniel Galicia, soliciting of Leo McClatchy any newspaper stories in the United States about the project. Writing in Spanish, Galicia referred in a March 25 letter to the process of "establicimiento del Parque Internacional 'Rio Bravo' [establishment of the Rio Bravo International Park]." Galicia then wrote to Conrad Wirth to thank the assistant NPS director "for all the courtesies shown me and the members of the Mexican Conference on the International Commission of Parks and Reserves." The Mexican forestry division chief was "very happy to know that you [Wirth] enjoyed the trip that we made in the sierra del Carmen, in the State of Coahuila, in order to establish the Mexican portion of the International Park of Peace between Mexico and the United States." He also wanted Wirth to know that "we are also working to gather all the necessary data on the formation of the National Park 'Rio Bravo' in Coahuila as part of the Big Bend in Texas." From this Galicia hoped that "soon we will be able to declare it a National Park although we are faced with legal difficulties insofar as the acquisition of the land is concerned." Galicia nonetheless anticipated "another International Conference," along with a visit from Wirth to Mexico "to show you some of the beautiful attractions which we have in my country." He then praised "the enthusiasm and patriotism of my superior Senor Ing. Miguel A. Quevedo," for "these places are now being converted into national parks." [28]

By late June, NPS officials had just begun to recoup the momentum on the international park interrupted by the deaths of Toll and Wright. Conrad Wirth discussed with park service director Arno Cammerer the need for another meeting with the International Commission. "As you know," wrote Wirth, "after the terrible accident, things were rather left up in the air." Yet the assistant NPS director reminded Maier that "we did make arrangements insofar as the international park at Big Bend is concerned, to meet with the Mexican authorities this fall and go over their proposed boundaries." Wirth then asked the NPS's Region III director to contact officials in Mexico to see if "they would have the material ready so as to be able to sit down and decide on the boundary lines and determine the final recommendations to be made to both Governments." Director Cammerer had planned to attend this gathering, said Wirth, who hoped that Maier could coordinate such a gathering in Mexico when the director also could meet with Texas officials regarding the bill to be placed before Lone Star lawmakers for purchase of lands on the American side of the Rio Grande for Big Bend National Park. Maier reported back to Wirth that he had spoken with Santos Ibarra, the commission member charged with identification of the Mexican boundary location. From Ibarra Maier had learned that "it has been a little difficult to determine . . . just how they [Mexican officials] intend to acquire their portion of the land." Compounding this situation, wrote Maier, was that "of course their idea of setting up a National Park has been quite different from ours, for the most part, because funds are not available to purchase immense areas." This procedure Maier described to Wirth as "in some cases they declare an area a national park, although there are private holdings within it, and in such cases they limit destruction of all plant and animal life, but do not force such land owners that may be within the area to immediately give up the land." Yet Maier conceded that the Mexican commissioners "are thoroughly in sympathy with our ideals, and this contact with our National Park Service will probably eventually lead to the same general policies as ours." To strengthen this bond, Maier noted that "when we were in Mexico City a trip for the Mexican officials was planned which would bring them up into Yellowstone and other National Parks in August and September." [29]

In preparation for the fall gathering of the international park commission, Maier assigned J.T. Roberts, associate landscape architect for Region III, to join Daniel Galicia in Alpine to study "the problem of boundaries for the proposed park." When the two departed for the Rio Grande on September 2, Galicia informed Roberts that his instructions from Miguel Angel de Quevedo "were to limit the boundaries, as far as possible, to the forested area because of the very limited funds available for use in obtaining land for park purposes." Galicia and Roberts had to leave their vehicle at the river town of Boquillas, Texas, because "the Rio Bravo [was] on a 6 foot rise." Taking a truck from the Mexican village of Boquillas, the party traveled along "the eastern and northern extremities of the Fronteriza Mountains," finding that "the timbered lands were mainly above 1780 meters, or approximately 5300 feet." Roberts would report to Maier that "for this reason Sr. Galicia first proposed an eastern and northern boundary from Mesa de los Fresnos to Mesa de los Tremblores." From there, wrote Roberts, the boundary line would extend "to Pico Sentinel, then north, including only the face of what we know as Del Carmine, then to Stillman at the end of the Boquillas Canyon." Roberts believed that "this would be similar to establishing the boundaries of the Chisos Mountain area by running a line from Mule Ears to Castillon Peak to Elephant Mountain to Crown Mountain to Lost Mine Peak and so on." The problem for the NPS architect was that "in this no consideration was given to the wild life or scenic values." He informed Maier that "with some difficulties in conversation I presented these points as we traveled along, and it was finally determined that the park should include all the mountain areas and such adjacent land necessary for the protection of wild life;" a decision that Roberts said "will include Pico Etereo." [30]

In order to redesign the Mexican portion of the international park, Roberts told the Region III director that "Sr. Galicia will recommend that the entire area within the original proposed boundaries be established as a game preserve, eliminating at once the value of the land for hunting." The NPS architect noted that Galicia "will then suggest that those owners within the boundaries of this area exchange their holdings for other excess forested areas now held by the Government." Roberts conceded that "the greatest trouble experienced by the department [of forestry, game and fish] is not with the native owners but with those owning 'The Club,' all of whom are citizens of the United States." Within the acreage owned by these foreigners, "the physical features," said Roberts, "may be described as very rugged, of volcanic origin and heavily timbered above 5300 feet." Among the species of timber were "Ponderosa pine, Mexican white pine, cypress, and fir, probably pseudopseudo douglasii." Roberts further reported that "below 5000 feet there is a great variety of trees, the most predominant being the oak and wild cherry." He contended that "sufficient water is available, all year, at The Club for a large development, and it may be found that there is an ample supply below the mine." Roberts indicated that "there are may other places, such as the Laguna and Carbonera, for overnight facilities." This latter locale was, "on the present trails, a three hour horseback ride from 'Casa del Nino' and four hours from The Club . . . at an elevation of 2170 meters (6500 feet)." Roberts estimated that "the distance between The Club and Casa del Nino is 28 kilometers [16.8 miles]," and he claimed that "it is between those two points that the most beautiful scenery was found on this inspection trip." Other distinctive features included an area "above the laguna, which is about 5 kilometers [three miles] north and east of Carbonera," which was called "Mesa Escondida where the largest timber of the mountains is found." Roberts also "found a cave described as being 'large enough to hide two hundred men and horses and with water convenient.'" The NPS architect then closed his report by noting that Galicia spoke less enthusiastically of "the eastern slope of the 'Del Carmine Mountains' — that is, the limestone uplift from Boquillas south." Roberts agreed that the area "is barren of trees and has no spectacular geological formations." Thus he concurred in "Sr. Galicia's point of view [that] it is of no value as a National Park and is in fact of interest only as a wild life refuge." [31]

Galicia's caution reflected the sentiments of his supervisor in Mexico City, Miguel Angel de Quevedo. While dedicated to natural resource preservation, Quevedo also knew of the political and economic realities of life in Mexico that constrained the Cardenas administration in its negotiations for an international park at Big Bend. As he prepared to attend the commission meeting in El Paso that fall, Quevedo advised Herbert Maier in September that he would accept NPS director Cammerer's invitation, "inasmuch as I have numerous problems I desire to clarify." American promoters of Big Bend National Park, however, saw only good fortune awaiting the deliberations of the international commission. Amon Carter's Fort Worth Star-Telegram trumpeted the windfall of publicity and tourism to come to the most isolated reaches of the Lone Star state. "Texans have a right to be enthusiastic about this development," declared the Star-Telegram on November 4, 1936, as "already the Big Bend park begins to take rank among the foremost on the national list." Carter's editors could hardly restrain themselves when calculating the benefits to accrue from the "millions of American holiday visitors" about to descend upon the "last frontier." Echoing the prose of Walter Prescott Webb, the Star-Telegram reminded its readers that "great mountain ranges on both sides of the river, gigantic abysses, towering peaks and crashing streams complete the region's attractions to the sightseer." Then the paper noted that "the international aspect of the park project enlarges its possibilities to an infinite degree." If possible, "the area in Mexican territory has been even more remote, more inaccessible, than that on the Texas side." This led the Star-Telegram to claim that joining the two countries in a venue covering some 1.2 million acres in "an international park freely open to the public of both nations — a sort of free port of recreation and fraternization — is a notable project in international relations." [32]

Four days after Franklin Roosevelt achieved the most sweeping victory in modern times in a presidential election, the director of the NPS arrived in Texas for a series of meetings on Big Bend and the adjacent Mexican park initiative. Historians have noted the energy that surged through the FDR administration in the days and weeks after his capturing of 61 percent of the nation's popular vote, and all but eight of the 535 electoral votes for president. Roosevelt and his staff believed that the public had validated their measures for reform, economic recovery, and protection of the nation's natural and cultural resources. Issues to be discussed at the El Paso gathering of federal officials from the United States and Mexico thus expanded to plans for reforestation along the border (a favorite of Miguel Angel de Quevedo), and a meeting of NPS officials and the "National Park Committee" of the West Texas Chamber of Commerce. Headed by Sul Ross's Howard Morelock, the entourage wanted to remind the park service of their own work on the acquisition of land for Big Bend, and of the need to highlight statistics about travel and economic development akin to those of the Star-Telegram's news story of the previous Sunday. [33]

When the international commission on parks and reserves came to order on November 9, the attendees represented the highest levels of natural resource management in both the United States and Mexico. NPS director Cammerer joined with his top assistants, Conrad Wirth and George Moskey, Herbert Maier of Region III, and Frank Pinkley, the longtime superintendent of Casa Grande National Monument who also served as the coordinator for the Southwestern Monuments network. Maier had invited his top assistant, Milton McColm, along with his chief biologist, Walter McDougall, Merel Sager of the surveying parties, and Everett Townsend, representing local interests in the international park initiative. Daniel Galicia led the Mexican contingent, which included game division chief Juan Zinser, Juan F. Trevino, and Juan Thacker. The International Boundary Commission likewise sent its highest ranking members from both countries: Laurence M. Lawson for the United States, and Joaquin C. Bustamante, the IBC's consulting engineer from Mexico. The NPS played for the commission a reel of film on the Big Bend region, followed by a presentation from Maier on the criteria used by both nations to determine the boundary lines of the international park. [34]

It soon became clear to the attendees that the demarcations of the joint initiative would be the most challenging task before them. Maier reported after the meeting that "it will be highly desirable that the east and west boundaries of the Mexican area, as nearly as practical, coincide with those of the Texas area where they join the Rio Grande." The commission members thus "agreed that the point where the Mexican boundary line will touch the River on the west should be the confluence of San Antonio Creek with the Rio Grande." The regional director then noted that "this will throw the Lajitas Crossing and its road for mining and cattle outside the area, which is desirable." Maier conceded that "while the eastern boundary of the Mexican area will contact the Rio Grande at the present proposed point," he realized that "the American line will be swung somewhat to the north so as to strike the Rio Grande at Los Vegas de Silwell [Las Vegas de Stillwell]." The attendees further decided that "probably only one vehicle bridge across the Rio Grande within the international park, crossing to the Mexican side, will be necessary and advisable for administrative and policing purposes." The future park management would have to consider, however, "that visitors should have free access to both sides, any Customs regulations being taken care of at the checking stations leading into each area." Then director Cammerer agreed that "it will probably be best not to run a main park road along the Rio Grande on the American side." Instead, the NPS director believed that "this should be left free for open wildlife range down to and across the border." [35]

After a luncheon hosted by the El Paso chamber of commerce, the commission heard from the IBC's Lawson, who showed them "very useful aerial surveys and aerial photographs of the Rio Grande." The group then revisited the boundary question, agreeing that "the present crossing at Boquillas for cattle and the mines could continue to operate even after the park is established." A primary consideration was the location of the road from Boquillas to Marathon along the eastern edge of the proposed Big Bend National Park. Several attendees noted that "mining activity on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande is almost extinct and the moving of cattle to the U.S. side is now of little consequence." Referring to "the small ranches now operating along both sides of the Rio Grande," Maier reported that "it was felt that the two governments, even though acquiring the land, might well extend permits to the owners of the land to remain for the remainder of their lifetimes." Then the regional director observed that "the boundaries of the American and Mexican side were corrected on the map by Daniel Galicia and Merel Sager and new photostats struck off and copies distributed to both delegations for future guidance." [36]

Following the discussions of boundaries and their locations, Conrad Wirth "suggested that on the basis of these lines the President of each country should be approached by the respective Departments and the two Presidents could then make final arrangements for the international aspects and proclamations." One detail that might hinder such collaboration was addressed by the IBC's Lawson, who "discussed the possible hydrographic considerations along the Rio Grande within, above and below the area in which it [the IBC] and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation may in the future be interested." Lawson led the commission to believe that "no major hydrographic project along the Rio Grande within the proposed area is now being considered." Yet several commission members had heard that "there may be a storage reservoir established immediately below the eastern U.S. boundary [of Big Bend]." Maier added in his report that "the fact that the present Irrigation Project on the Mexican side along the Conchos River, running into the Rio Grande above the area, may in time consume the major part of the water at present flowing into the Rio Grande proper below this point and through the proposed park;" a point which the attendees agreed was "of marked importance." The El Paso conferees concluded, however, "that once the international park is established an adjustment in the operation of the Conchos River irrigation project may be effected by the Mexican government so as to prevent this threatened consumption of the main source of Rio Grande water within the park area." [37]

For promoters of Big Bend National Park, the good news from El Paso coincided with their campaign to lobby the Texas legislature in January 1937 for funds to purchase the private land in Brewster County needed for the park. Milton McColm wrote to Arthur Brisbane of the King Features Syndicate in New York City, to encourage the national journalist to "comment in your column 'TODAY,' on the proposed Big Bend International Park that would link 788,000 acres in Texas . . . to approximately 400,000 acres on the opposite side of the Rio Grande, in the Mexican States of Chihuahua and Coahuila." McColm noted that plans now called for two separate national parks, each "under the supervision of its respective government." Texas thus would have its first NPS unit, while "the International Park, it is believed, would tend to cement existing friendly relations between the two nations." This latter point, McColm hoped, would appeal to Brisbane's nationwide readership. "Director Arno B. Cammerer . . . has stated," wrote McColm, "that the establishment of such an international park, dedicated to Peace, in which the rank and file of both nations may freely mingle on both sides of the international boundary in their hours of leisure and recreation, and unrestricted by customs and similar regulations, may set an example to other nations." Speaking as if Cammerer's words soon would come to fruition, McColm concluded that the initiative "marks an outstanding step in the recreational field." [38]

McColm's solicitation of Arthur Brisbane's support indicated the national level of interest that the park service hoped to reach with its publicity on the international park. Another approach that the NPS took was to endorse the concept in an article in the December 1936 issue of the journal American Forest. The Mexican department of forestry, game and fish then reprinted the story in Spanish as "El Parque de la Paz de Mexico." This allowed Mexicans to read for the first time in a national publication of the wonders of the proposed international park in Coahuila and Chihuahua, complete with photographs from the February 1936 journey of U.S. and Mexican members of the international park commission. Howard Morelock wasted little time in capitalizing on this new mood of cooperation, contacting Texas state representative R.A. Bandeen with "a tentative draft of a resolution covering the 'Good Will Trip' to Old Mexico." The Sul Ross president wanted to take a group of state lawmakers to Mexico to impress upon them the sincerity of the Mexican government. To strengthen his case, Morelock asked Everett Townsend to review the proposal, which the longtime park advocate did in language revealing the delicate nature of negotiations behind the optimistic public pronouncements. Townsend cautioned Morelock to avoid use of the term "international park" without references to the specific control that each nation would have over their territory. "We want to breathe as much peace and good-will as possible throughout the whole document," wrote Townsend. He also wanted the Sul Ross president to emphasize that the trip to Mexico "would be for the consummation of this great International Peace Park or play-ground — the first thing of the kind ever attempted between non-related nations." Yet Townsend found himself in the unlikely position of correcting Morelock over the tone of the resolution. "I just know that you can do better than the sample that I have," he wrote. "You must remember that those people South of the Rio Grande love a lot of flowery language," Townsend concluded, "and of course, the Resolution will be made public down there, and we want it to please them as much as possible." [39]

While publicity circulated nationwide in favor of the international park idea, Mexican and United States commissioners in April 1937 addressed the boundary issue in separate surveys. A problem soon arose when IBC and NPS officials realized that the eastern and western limits of the international park did not intersect. J.W. Ayres of the Region III office learned when he arrived in El Paso that neither the U.S. nor the Mexican IBC agents had copies of the maps corrected the previous November by Daniel Galicia and Merel Sager. Ayers did report to Maier on April 16 that "Lawson's mosaic map has pencil cross at approximate location to which Bustamante has agreed." He then noted that the American IBC surveyors would travel to Big Bend "to establish a mark at each point consisting of metal disk cemented in rock with six foot wooden monument painted aluminum over it." The IBC's Lawson wanted these markers "located for latitude and longitude by stellar observation and later tied into existing triangulation system." Ayers met with Lawson's crew in Terlingua, and proceeded to the CCC camp in the Chisos Mountains prior to spending a week on the Rio Grande. Upon completion of their work, the western boundary markers had been placed at Latitude 29 degrees 14' 48", Longitude 103 degrees 40' 17"; while the eastern marker was placed at Latitude 29 degrees. 22' 09", Longitude 102 degrees, 50' 47". [40]

Marking the parameters of an international park proved easier than convincing Texas legislators to fund the acquisition of land on the American side for their state's portion of this historic initiative. As word filtered down to Mexico in June 1937 that Texas governor James Allred might veto the Big Bend appropriation of $750,000, Herbert Maier decided to enlist the aid of Mexican officials engaged in the international park process. Pierre deL. Boal, charge d'affaires for the U.S. embassy in Mexico City, contacted Secretary of State Cordell Hull on June 7 to advise him of a conversation that had taken place that day between himself and Daniel Galicia. Maier had asked Galicia to contact U.S. ambassador Josephus Daniels for a letter to Governor Allred in support of the bill, adding the benefit of the international park to the larger scope of the Texas governor's action. Galicia's supervisor, Miguel Angel de Quevedo, also acceded to Maier's request for Mexican support, by writing Boal on June 7. "I beg to inform you," Quevedo told the American charge d'affaires, that "the establishment of the Sierra del Carmen National Park in the States of Coahuila and Chihuahua contiguous to the Big Bend National Park in the State of Texas having been approved in principle by the President of the Republic, these two parks to be combined, at the suggestion of the American Government, into an International Peace Park - the Matter now awaits the conclusion of topographical studies now being made, and the drafting of the (Presidential) Resolution making this area a National Park." Given the advanced status of study, said Quevedo, he hoped that Boal would ask ambassador Daniels "to lend his valuable cooperation in asking the Governor of the State of Texas to approve the appropriation" of the funds for Big Bend. Daniels, well-liked by the Mexican people for his understanding of their culture and historical realities, and identified by Maier as having a "personal interest in the project," had no time to influence Allred before his veto of the Big Bend bill. Daniels, however, did meet in Washington with NPS director Cammerer to voice his support of the park, and to "hope that it is only delayed" by Allred's rejection of the funding measure. [41]

Solicitation of Mexican support for the Big Bend funding bill prompted Quevedo and his department to publish in El Diario Official an acuerdo (an accord or agreement) about national parks in Mexico. Boal sent a copy to the NPS in Washington, as he believed "that this order may have some relation to the establishment and protection of the International Park around the Big Bend area of Texas." Drafted on April 28, signed by President Lazaro Cardenas, Cabino Vasquez, chief of the Agrarian Department, and Quevedo, but not printed until June 7 (at the height of the lobbying campaign against Allred's veto), the acuerdo declared "unaffectable the National Parks in the matter of ejidial dotations and restitutions." Recognizing the need to preserve Mexico's forests to avoid erosion, and because "the country requires places or spots where nature appears in its wild state, as living and real examples of what virgin forests and wild fauna are in their primitive state," the Mexican federal government "considers it essential to submit [national parks] to a special system of control (regimen especial)." This process would be in addition to "issuing measures tending to insure the utilization (aprovechamiento) of the grasses, dead wood and other products (demas esquilmos) which neither harm nor destroy those parks, for the exclusive benefit of the ejidos or nuclei of rural population immediately adjacent to them." [42]

To explain the meaning of this paradigm shift in Mexican natural resource policy, the American embassy in Mexico City drafted a statement for officials in Washington. William P. Bowen of the embassy staff suggested that "this provision appears to be a withdrawal of Mexican Federally owned lands of national park character from the right of acquisition by the Mexican peasant under . . . both the Agrarian and idle land laws, and a regulation of the use of certain products of the areas of national park character." Bowen then asked his Mexican counterparts to explain the history of their country's land laws, so as to place the June 7 acuerdo in perspective. His synopsis for State department officials revealed the painful legacy of the "Porfiriata" (1880-1910), "during which foreigners and foreign capital were given every privilege in Mexico" by the regime of Porfirio Diaz. After the revolt in 1910, "men of Indian or Mexican blood came into power," followed by "a great wave of nationalism with the slogan 'Mexico for Mexicans' — Mexicans being the Indian population of the country." Bowen wrote that the task of land reform for the revolutionaries was daunting, in that "many of [the Spanish-era] haciendas were of unbelievable size, measured in miles rather than acres, and in many instances were held by absentee landlords." This meant that "the Indian populations of these plantations had been reduced to serfdom and virtual slavery." [43]

Of significance to American policymakers, wrote Bowen, was the fact that "the coming to power of the Mexican, the advance of socialism, and the cupidity of the politician gave rise to the theory that the Spanish landlord, just as Americans, Germans, etc., were aliens and that they had despoiled the Indian of his rights." This concept held "that the land rightfully belonged to the peasants." In "working on that theory," said the American embassy official, "a great number of the vast estates were confiscated by the State — depending, I was told, upon which side of the political fence the owner stood." In so doing, "title was by decree vested in the State, [and] bonds, in an amount which the Government found as due the divested owners, were issued to the landlords." At this juncture "the former peasant made application to the Government for a parcel of land for which he was to make stipulated annual payments, which payments were to retire the bonds held by the former landowner." Bowen compared this process to "the settlement of the Irish Land Question," and "the system was called restitution of the land to the Indians." [44]

The most challenging issue of the acuerdo remained the selection of lands for national park status. Bowen admitted: "I have no knowledge of the idle land laws, but it seems logical that they would be laws relating to lands in Government ownership that have not been 'restored' to the Indians." He also found that "there is no English word 'unaffectable,' but in a breakdown of that coinage, we would get 'not capable of being affected.'" The term ejido had a more straightforward meaning ("a public common held by a pueblo or the like"). As to the term "dotation," Bowen claimed that it was "an [endorsement] or the giving of funds (in this case lands) to a public institution." The embassy official read this section "to mean that those areas which have been set aside as national parks, are removed, by this order, from the provisions of the laws governing the endowment of villages with lands for commons." In addition, said Bowen, such status meant "reserving them from the provisions of the laws governing restitution of lands to the peon — that is, they are not to be used for either purpose." In the case of proposed national parks, Bowen read the language of the acuerdo to prohibit release of such lands wherever a park was being surveyed. He then closed with an explanation of the language permitting local landowners to use the natural resources of future national parks. Bowen believed that "the provision in this order is to require that before attempting to use the products they must first consult the Agrarian Department, to determine whether such use will harm or destroy the park, and to obtain permission for such use." [45]

The fall of 1937 was a critical period for Mexico, the United States, and the fate of the international park. As the Texas legislature would not reconvene for another eighteen months, the issue of land acquisition on the American side of the Rio Grande looked unpromising. In Mexico, workers in American-owned oil fields went on strike demanding higher wages; a circumstance that led the following March to the bold move by the Cardenas administration to nationalize all oil production in Mexico (and endanger both the "Good Neighbor" policy and the international park). Yet proponents of Texas's first national park persisted in their efforts to link the two nations by means of publicity and news coverage.

One intriguing moment in this campaign occurred in October, when Leland D. Case, editor of The Rotarian: The Official Magazine of Rotary International, wrote to Leo McClatchy upon receiving word of the international park initiative in the Southwest. Six decades later, Rotary International would campaign aggressively for creation of a park between Mexico and the United States like that of Waterton Lakes-Glacier International Peace Park, an initiative that Rotary had orchestrated in 1932. Rotary had expressed no interest in the Big Bend idea when developing the Canadian-American park, and Case revealed his ignorance of this oversight when he asked McClatchy: "Are there any other international parks in which the United States is concerned . . . ?" Case had planned an issue of The Rotarian devoted to "International Peace Monuments on national boundaries," and McClatchy revealed no sense of irony in his reply. The Region III publicist noted that the "International Peace Gardens" existed on the border between North Dakota and Canada, although this was "strictly a State Park, and there is no international angle." More appealing to Rotary, said McClatchy, was Big Bend, which "would merge areas occupied by two different races — people with different languages and different customs." The NPS official thought that this "would be a big step in the direction toward which Rotary points — the promotion of international good will." In addition, he told Case, "it would lead generally to a better understanding between Mexico and the United States, and it should tend to cement the existing friendships between those two countries." It was McClatchy's hope that The Rotarian would focus upon Big Bend, but would be grateful if Case folded that story into a larger narrative about borders in general and their parks for peace. [46]

McClatchy could not know that the last official action taken by either government to ensure creation of the international park occurred on October 16, 1937. On that date, the government of Mexico accepted the boundary markers on the south side of the Rio Grande across from the American markers. Overshadowing the dreams of park advocates was the deterioration of relations between Mexico and the United States, in addition to the looming crisis in Europe that would explode in September 1939 as the Second World War. Friedrich Schuler wrote in Mexico Between Hitler and Roosevelt: Mexican Foreign Relations in The Age of Lazaro Cardenas, 1934-1940 (1998), that "whereas 'experimentation' had been the central paradigm for the period between 1934 and 1936, by 1937 the new central theme would be 'survival.'" The Mexican economy had not improved materially with three years of Cardenismo, even as the American economy softened after the first term of the Roosevelt New Deal. Schuler contended that Secretary of State Cordell Hull "saw Mexico's crisis as an opportunity to extract concessions from Mexico first and help the southern neighbors later." Then in the months after the nationalization of foreign oil interests, said Schuler, "even the staunchest Cardenas supporters were rethinking their personal commitment when the government failed to pay wages, left rural banks unfunded, and did not stop the rise in food costs." Michael Meyer and William Sherman elaborated on this challenge to Mexico and America by noting that "many United States newspapers expressed outrage, and not a few politicians called for intervention to head off a Communist conspiracy on the very borders of the United States." [47]

No better statement of the chilling effect of oil nationalization on the international park could be found than the cryptic letter of November 21, 1938, from Conrad Wirth to NPS director Cammerer. "There are no new developments in connection with the Mexican side of the proposed park," Wirth reported, other than the approval by both nations of the boundary markers. Yet the NPS could not report to Mexican officials any success in the campaign to raise $1.5 million dollars in private funds for land acquisition, nor in the effort to revive the vetoed Texas legislation for state purchase of the future Big Bend National Park. Then a minor controversy arose in 1939 when NPS planners discovered that they had no official measurement of the Mexican portion of the international park. Ross Maxwell, the junior geologist for the NPS's Region III, turned to Everett Townsend for help in determining where the Mexican and U.S. officials had traveled in search of boundary sites. When the surveying parties had gone to the South Rim, wrote Maxwell, "Sr. Daniel Galicia asked Mr. Townsend to point out certain landmarks in Mexico that had been selected by the Mexican Government as points of boundary for the park." Relying upon Townsend's vast knowledge of the border region, Galicia and his Mexican colleagues sketched out an area of some 900,000 acres that would constitute the southern portion of the international park. [48]

Once the park service learned of the actual dimensions of the Mexican land base, they discovered a discrepancy in the eastern markers for both countries. Conrad Wirth informed Region III officials that their reliance on the drawings made at the 1936 El Paso conference by Daniel Galicia had not been followed carefully. He had determined that "the eastern Mexican boundary coming to the Rio Grande at Rancho Stillwell on a tangent from the [promontory] called Pico Eterea" should be relocated "four miles north opposite the mouth of Stillwell Creek." Wirth suggested that Galicia had relied upon maps that did not include Stillwell Creek, and concluded that "he inadvertently drew the line to Rancho Stillwell believing it to be at the mouth of Stillwell Creek." The NPS assistant director then asked Ross Maxwell to research this dilemma, and the junior geologist reported that "the apparent misunderstanding as to the erection of monuments near the Rio Grande marking the eastern limits of the Big Bend International Park Project in Mexico and Texas appear to have developed because of the questionable location of the Stillwell ranch." Maxwell's study found that "the Stillwells apparently ranched temporarily anywhere in southern Brewster County, Texas and the adjacent parts of Mexico where they could find grass and water." This resulted in "old Stillwell ranches at several localities in that area." In particular, said the geologist, "two Stillwell ranches are indicated on the U.S. Geol. Survey Topographic map, the Chisos Mountains quadrangle, within the proposed park," while "several sites were used by the [Stillwells] that are not included in the present proposed boundary." [49]