|

Biscayne National Park Florida |

|

NPS photo | |

Biscayne National Park has the simple beauty of a child's drawing. Clear blue water. Bright yellow sun. Big sky. Dark green woodlands. Here and there a boat, a bird. It is a subtropical place where a mainland mangrove shoreline, a warm shallow bay, small islands or keys, and living coral reefs intermingle. Together they make up a vast, almost pristine wilderness and recreation area along the southeast edge of the Florida peninsula. The park, located 21 miles east of Everglades National Park, was established as a national monument in 1968. In 1980 it was enlarged to 173,000 acres and designated as a national park to protect a rare combination of terrestrial and undersea life, to preserve a scenic subtropical setting, and to provide an outstanding spot for recreation and relaxation.

In most parks land dominates the picture. But Biscayne is not like most parks. Here water and sky overwhelm the scene in every direction, leaving the bits of low-lying land looking remote and insignificant. This is paradise for marine life, water birds, boaters, anglers, snorkelers, and divers alike. The water is refreshingly clean, extraordinarily clear. Only the maintenance of the natural interplay between the mainland, Biscayne Bay, keys, reefs, and the Florida Straits keeps it that way. The Caribbean-like climate saturates the park with year-round warmth, generous sunshine, and abundant rainfall. Tropical life thrives. The land is filled to overflowing with an unusual collection of trees, ferns, vines, flowers, and shrubs. Forests are lush, dark, humid, evergreen; many birds, butterflies, and other animals live in these woods.

No less odd or diverse is Biscayne's underwater world. At its center are the coral reefs. Unlike the ocean depths, which are dark and nearly lifeless, the shallow water reefs are inundated with light and burgeoning with life. Brilliantly colorful tropical fish and other curious creatures populate the reefs. Their appearances and behavior are as exotic as their names—stoplight parrotfish, finger garlic sponge, goosehead scorpionfish, princess venus, peppermint goby. A reef explorer can spend hours drifting lazily in the waters above the reefs and watch a passing procession of some of the sea's most fascinating inhabitants.

Whether on the reefs, the keys, the bay, or the mainland, you leave behind what is familiar and become acquainted with another world that is strange and wild. Biscayne is a different sort of national park. Expect the unexpected.

Mainland

In Biscayne the mainland mangrove shoreline has been preserved almost unbroken. For many years these trees of tropical and subtropical coasts were considered almost worthless. Some were cut for timber or used to make charcoal. As recently as the 1960s the mangrove wilderness was referred to as "a form of wasteland." Like thousands of other wetlands, it was cleared or filled to make way for harbors and expanding cities.

Now we understand that the mangroves are vital to the well-being of the park and surrounding areas. Without them, there would be fewer fish for anglers and fewer birds for birdwatchers. Biscayne Bay would become murky. Areas inland would be exposed to the full violence of hurricanes.

Beyond the Darkness

It is hard to see what lives in the brackish waters of the mangrove

swamps because this water is stained brown by tannins from the trees.

Hidden among the maze of roots is a productive nursery for all sorts of

commercial, sport, and reef fish. Here the young find shelter and food.

Fallen mangrove leaves feed bacteria and other microorganisms, and so

begins a food web that supports not only underwater life but also birds

that nest and roost in the tree tops.

Defending the Coast

The mangrove forest appears as a nearly impenetrable fortress. Perhaps a

snake or mosquito can move through easily, but little else can. It makes

an effective buffer between the mainland and Biscayne Bay.

Mangroves guard the bay from being dirtied by eroded soil and pollutants washing from the land by trapping them in its tangle of roots. The trees also stand as a natural line of defense against the stron wind and waves of hurricanes.

Freaks of Nature

Mangroves have been called freaks, and a close look reveals why. Roots

of the red mangrove arch stilt-like out of the water or grow down into

the water from overhead branches. The roots of the black mangrove look

like hundreds of cigars planted in the mud—they are the breathing

organs necessary for survival in this waterlogged environment.

Bay

"The water of Biscayne Bay is exceedingly clear. In no part can one fail to clearly distinguish objects on the bottom ...," biologist Hugh Smith wrote in 1895. Today the shallow waters of this tropical lagoon are still remarkably transparent. They serve as a blue-green tinted window to a world of starfish, sponges, sea urchins, crabs, fish of all sizes and kinds, and hundreds of other marine plants and animals.

The bay is a reservoir of natural riches, teeming with unusual, valuable, and rare wildlife. It is home for many; a temporary refuge and feeding ground for others; and a birthplace and nursery for still others. It is a benign powerhouse, designed to draw energy from the Sun and use it to support a complex and far-reaching web of life.

The manatee is one unusual animal that depends on this web. This gentle blubbery giant visits the bay in winter to graze peacefully on turtle and manatee grasses. It is the water's warmth and ample food supply that attracts this endangered marine mammal.

Sanctuary for Birds

Birds are drawn to the bay year-round. Each follows its own instincts

for survival. Brown pelicans patrol the surface of the bay, diving to

catch their prey. White ibis meander across exposed mud flats, probing

for small fish and crustaceans.

Large colonies of little blue herons, snowy egrets, and other wading birds nest seasonally in the protected refuge of the Arsenicker Keys. The extremely shallow waters surrounding these mangrove islands in the south bay are especially well suited for foraging.

History of Abundance

The coastal wilderness of south Florida was the first spot in North

America explored by Europeans. Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon sailed

across Biscayne Bay in search of the mythical Fountain of Youth in

1513.

Later travelers like land surveyor Andrew Ellicott recorded the bounty of life in the region. "Fish are abundant," Ellicott wrote in 1799. "[Sea] Turtles are also o be had in plenty; those we took were of three kinds; the loggrhead, hawk-bill, and green."

In the 1800s and early 1900s many settlers of the keys earned their living from the bay. Among them were Key West fishermen who collected and so ld the fast-growing, "fine-quality" bay sponges.

Underwater Crossroads

Today commercial fishermen, anglers, snorkelers, and boaters still reap

bountiful rewards from the bay. The bay's good-health is reflected in

the numbers of different kinds of fish—over 250—that spend

part of their lives in it.

Many of the fish that dazzle snorkelers and divers on the coral reefs by day feed in the bay at night. Like the mangrove shoreline, the bay plays a critical role as a fish nursery. The young of many coral reef fish, like parrot and butterfly fish, and sport fish, such as grunts, snappers, and the highly prized Spanish mackerel, find food and shelter from big hungry predators in the bay's thick jungle of marine grasses.

Images of the Bay

Peering into the crystal waters of Biscayne Bay, it is hard to imagine

either its past or its future as clouded. The bay seems suspended in

time.

While neighboring Miami-Dade County has mushroomed into a metropolis of over 2.2 million people, the bay appears to have captured the magic of the Fountain of Youth that eluded Ponce de Leon. It has remained beautiful and relatively unspoiled. Though thousands of years old, it is still vibrant with life. But, this has not always been true.

Early in the 1900s parts of the bay were dying. In some northern areas of the park pollutants poisoned the bay, and construction runoff spilled suffocating amounts of sediments. Today after years of cleanup, the north bay is recovering and the rest of the bay remains nearly pristine.

In 1895 biologist Hugh Smith declared that Biscayne Bay was "one of the finest bodies of water on the coast of Florida." In another hundred years—if well-protected—it still could be.

Keys

About 100,000 years ago the Florida Keys were under construction. The builders were billions of coral animals, each not much larger than a period or a dot on this page. Together these animals built a 150-mile-long chain of coral reefs. When these reefs later emerged from the sea, they became the islands of the Florida Keys. If you look closely, you can see fossil coral rock on the islands of Biscayne.

Tropical Paradise

Gumbo limbo. Jamaican dogwood. Strangler fig. Devil's-potato. Satinleaf.

Torchwood. Mahogany. Only tiny pockets in South Florida contain this

mixture of tropical trees and shrubs common in the West Indies.

North-flowing air, ocean currents, and storms delivered the pioneer

seeds and plants that eventually grew into the islands' lush,

jungle-like forests.

Walking along a trail in these hardwood hammocks, you may see other tropical natives. Zebra longwing butterflies and endangered Schaus swallowtails find refuge in the tangle of leaves and vines. Golden orb weavers betray their presence with large yellow spider webs. Birds and a few mammals share these isolated, mangrove-fringed keys.

American Indians to Millionaires

Over the years the keys

attracted people willing to risk the chance of a hurricane and the

certainty of pesky bugs. American Indians were first. Tree-cutters from

the Bahamas came later and felled massive mahoganies for ships. Early

settlers on Elliott Key cleared forests and planted key limes and

pineapples. Subtropical forests throughout the keys were destroyed.

Biscayne preserves some of the finest left today.

The islands abound with legends of pirates and buried treasure. Shipwrecks, victims of high seas, and treacherous reefs lie offshore. Fortune hunters, boot leggers, artists, gamblers, millionaires, and four United States presidents have spent time on the keys of Biscayne.

Reef

Dive into the undersea realm of the coral reefs, and you will discover a feast for the eyes. It is a living kaleidoscope of gaudy colors, bold patterns, intricate designs, and peculiar shapes. Alien, yet inviting, the life of the reefs excites and mystifies snorkelers and scientists alike.

Reef Builders

Among the most puzzling creatures are the corals. Early biologists

suspected they were plants. But each coral—each brain, finger, or

staghorn coral—is actually a colony of thousands of tiny,

soft-bodied animals. These animals called polyps are relatives of the

sea anemone and jellyfish. Rarely seen in the day, the polyps emerge

from their hard, stony skeletons at night to feed, catching drifting

plankton in the1r outstretched tentacles. These primitive, unassuming

animals are the mighty master reef builders. The creation of one reef

requires the effort of billions of individuals. Each extracts building

material—calcium—from the sea and uses it to make itself a

protective tube-shaped skeleton. Hundreds of these skeletons make a

coral. Many corals, growing side by side and one on top of the other,

form a reef.

Corals are very particular about where they build reefs. Like the offshore seas of Biscayne, the water must be the right temperature (no cooler than 68°F), the right depth (no deeper than 200 feet), and be clean and well-lit. Such conditions exist along the Florida Keys in and south of Biscayne and in the Caribbean, and in other tropical oceans.

Undersea Metropolis

Reefs are the cities of the sea. In and around them lives a huge,

diverse population of fish and other marine creatures. Every hole, every

crack is a home for something. Some inhabitants, such as the Christmas

tree worm, live anchored to the coral. There is food to satisfy all

tastes. Fish and flamingo tongues (snail-like mollusks) eat coral. Fish

are food for other fish and, quite often, for seafood gourmets.

Fishes of the Reef

"In variety, in brilliance of color, in elegance of movement, the fishes

may well compare with the most beautiful assemblage of birds in tropical

climates," Louis Agassiz, 19th-century French naturalist, wrote after

visiting the Florida reefs. Reefs host the world's most spectacular

fish. Along Biscayne's reefs are more than 200 types of fish. Some are

impressive in size, others in color. Some seem grotesque, others

dangerous—or are they? Many behave in bizarre, unexplainable ways,

at least to humans. Few places on Earth match the diversity of life in

the reefs' underwater wilderness.

A Sea of Color

Imagine the most colorful scene you have ever seen—a field of

wildflowers, glittering lights or a city at night, a desert sunset.

Whatever it is, the dazzling spectrum displayed by reef fish will equal

or surpass it. The range extends from the flamboyant—angelfish,

wrasses, parrotfish, and neon gobies—to fish that seem drab and

ordinary.

There is much speculation about what role the colors play. The answer differs for each fish. An eye-grabbing wardrobe may serve as a kind of billboard, advertising a fish's presence. Vividly colored wrasses attract other fish in this way so they can clean them of parasites and dead tissue, getting a meal in return. Multicolored bars, stripes, and splotches blur the outline of other fish, making it difficult for predators to see them against the reef's complex background. Some fish are masters of disguise. Many turn different colors at night, presumably to hide from nocturnal predators. The camouflaged moray eel blends in with its surroundings. Unsuspecting fish that swim too close often get caught between the eel's powerful jaws and needle-sharp teeth.

A Montage of Motion

Morays are sedentary creatures, but most fish swim freely about the

reefs. Some, like the solitary angelfish, move with deliberate grace.

Others dart about in schools of thousands, moving with the precision of

choreographed dancers. Each close-knit group offers protection to its

members. Reef fish are noted for their eccentric behavior. One is the

sharp-beaked parrotfish. It can be seen and even heard, munching on

coral. Odd meal for a fish? Not really. Along with rock, the parrotfish

is devouring algae and coral polyps.

Exploring Biscayne

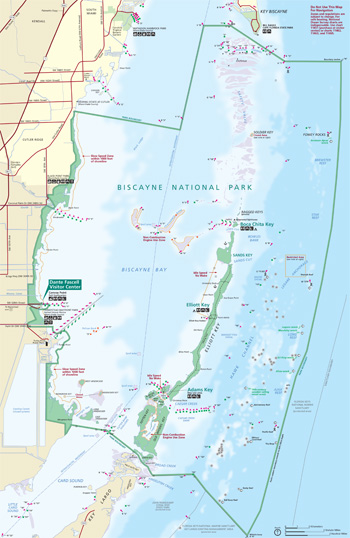

(click for larger map) |

On the Mainland

Convoy Point Park headquarters and Dante Fascell Visitor Center are at Convoy Point. The visitor center has exhibits, theater/gallery, a bookstore, and schedules of activities. Convoy Point has a picnic area with tables, fire grills, restrooms, and a short trail with views of birds and marine life.

Boat Tours A concessioner offers glass-bottom boat tours, snorkeling and scuba diving trips to the reefs, and occasional island excursions for picnicking and hiking. All tours leave from Convoy Point. The concessioner rents snorkeling and scuba equipment, kayaks, and canoes.

Accommodations and Services Homestead, Miami, and the Florida Keys have hotels and motels; reservations are recommended. They also have restaurants, service stations, groceries, and other stores. Nearby public marinas have boat launch ramps and fuel, and often charter or rent s il and motor boats.

Camping There are no campgrounds on the park's mainland. See "On the Keys" (below) for information about island camping; these campsites are reached only by boat. Nearby private mainland campgrounds and trailer parks in Homestead, Florida City, and South Miami have spaces for tents, mobile homes, and trailers. Everglades National Park, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, and other area parks have campgrounds, open year-round.

General Information

Climate Biscayne has warm, wet summers (May through October) and mild, dry winters (November through Apri l). Expect sunshine and high humidity year-round. High temperatures average in the high 80s to low 90s°F in summer and mid-70s to low 80s°F in winter. Annual rainfall fluctuates, but 85 inches or more is common. Most rain falls in summer in brief afternoon thunderstorms. Summer and fall are seasons for hurricanes and tropical storms.

Safety and Regulations • The park is a wildlife and historical preserve—do not disturb or remove natural or historical objects. • Loaded firearms, explosives, and other weapons are prohibited. • Pets must be on a leash no longer than six feet and are restricted to certain areas of the park. • Fires are allowed only in campstoves or designated grills. • Be careful wading; coral rock is sharp. • There are no lifeguards; do not swim alone. • Mosquitoes and biting insects are here year-round but are fewest January to April. Use insect repellent • If camping, be sure your tent has bugproof netting. • Wear waterproof sunscreen. • Emergencies call 911.

Getting to the Park The main north-south highways approaching Biscayne are Florida's Turnpike and U.S.1. The most direct route to Convoy Point is via SW 328th Street, which intersects U.S.1 in Homestead. Driving south on the turnpike, you can reach SW 328th Street by taking Speedway Blvd. south (SW 137th Avenue), then follow signs. The rest of the park is accessible only by boat.

On the Water

The Florida Straits and Biscayne Bay offer great year-round recreation. You can enjoy saltwater fishing in all seasons. Marlin and sailfish are popular ocean catches. Snapper and grouper are caught in the bay; Florida fishing licenses required—obey regulations on size, number, season, and method of take.

You can take stone crabs in season and blue crabs year-round. Lobsters are protected in the bay and tidal creeks but may be taken on the seaward side of the keys in season. Waterskiing is allowed; avoid mooring sites and watch for swimmers and divers.

Closed Area-Legare Anchorage No stopping, swimming, diving, or snorkeling is allowed. Underwater viewing devices, like cameras and glass bottom buckets, are prohibited. Do not anchor vessels. Drift fishing and trolling are allowed.

Rules and Safety Tips Caution: navigating the shallow waters of Biscayne can be tricky. Water depths on nautical charts represent the average depth at low tide—levels may be lower or higher. In Biscayne Bay low and high tides occur later than the times listed in the tide tables for Miami harbor entrance. In the southern part of the bay, low tide occurs as much as 3½ hours later and high tide as much as 2½ hours later.

Pre-sailing Checklist You must take this gear when boating: U.S. Coast Guard-approved personal flotation device (PFD) for each passenger, fire extinguisher, and signaling equipment. Take enough fuel for a roundtrip. Tell someone where you are going and when you expect to return. Before leaving shore, check weather forecasts, sea conditions, and tides.

Safety Afloat Stay alert! Watch weather closely. Storms move quickly, bringing rough seas and the danger of lightning. Monitor marine weather radio broadcasts. If a storm breaks seek the nearest safe harbor.

Caution Shallow Water • Use caution if boating near shallow areas or reefs. Striking the bottom with your propeller can kill corals or grassbeds and may damage your propeller or engine cooling system or hull. • Look out for manatees; propellers cause injury and death to these endangered mammals. • Watch for swimmers and divers near moored boats or in an area where they might be expected. Stay 300 feet away from a diver's flag. If you leave your boat to swim, anchor it securely. Don't let currents, which are strongest on the outer reefs and in cuts between the keys, carry you or your boat away.

On the Keys

The keys can be reached only by boat. Developed recreation areas and services are limited to a few islands. Boat fuel, supplies, and food are not sold on any island, but they are available at main land marinas. Only Elliott Key has drinking water.

Elliott Key Boat docks are located at Elliott Key Harbor and at University Dock A campground with picnic tables and grills operates on a first come, first-served basis. Drinking water, restrooms, and showers are nearby. Popular overnight anchorage sites are offshore. The island has a self-guiding nature trail.

Adams Key A free boat dock, a picnic area, restrooms, and a trail are available for day use.

Boca Chita Key A cleated seawall, picnic area, hiking trail, and restrooms are available. A campground with grills and tables operates on a first-come, first-served basis. An ornamental lighthouse is open intermittently.

Sands Key Overnight anchorage sites are located offshore.

Rules and Safety Tips The entire park is a wildlife refuge. DO NOT FEED WILDLIFE. Raccoons become pests when humans feed them. Arsenicker Keys are particularly important as a bird nesting area; do not disturb these keys. West Arsenicker Key, Arsenicker Key, and the islands in Sandwich Cove are closed to the public. Pack out all trash on the keys. Some private property still exists on the keys; please respect owners' rights. A few tropical plants can cause painful itching; do not touch any plants that you don't recognize as harmless.

Fees There is a $15 per night overnight dockage fee at Boca Chita Key and Elliott Key harbors, which includes a $10 camping fee Group campsites are $25.

Pets Leashed pets are permitted only in the developed areas of Elliott Key and Convoy Point.

On the Reefs

Reef exploring is best on calm, sunny days. Both the outer reefs, along the park's eastern boundary, and the patch reefs, closer to shore, offer good snorkeling and diving.

Strong currents can occur on the outer reefs. Unless you are experienced; stay on calmer patch reefs. Reef guidebooks are sold at Dante Fascell Visitor Center. Mooring buoys are available on some of the patch reefs. Check with a ranger for buoy locations. Ask at the visitor center about the Maritime Heritage Trail.

Protecting Yourself and Safety Tips Use caution when you visit the reefs. All snorkelers and divers must display the standard diver's flag to warn boaters of their presence. Be aware of other boats in your area; propellers have injured divers. Never swim alone—always have another person stay on board.

Reef animals generally will not harm you if you leave them alone. It is good practice not to touch anything, even if it looks harmless. Coral can cause deep, slow-healing cuts. Attacks by barracuda or sharks rarely occur, but both are considered dangerous and should be watched carefully. Ask a ranger about hazards before you venture out.

Protecting the Reef A coral reef is alive. If your boat hits a reef, it will damage your boat, scar the reef, and kill coral animals. You are subject to a fine and may be liable for the cost of restoring the damaged resource. Watch for coral heads near the surface if boating near patch reefs. Anchors can damage reefs; anchor in a sandy bottom or use a mooring buoy. Standing or sitting on coral or grasping it can cause injury. Do not disturb reef inhabitants. Resist the temptation to take home a souvenir—this is illegal and diminishes the beauty of the reef. Cultural artifacts are also protected; do not remove them.

Source: NPS Brochure (2007)

|

Establishment

Biscayne National Park — June 28, 1980 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Paleoecologic Reconstruction of the History of Featherbed Bank, Biscayne National Park, Biscayne Bay, Florida USGS Open-File Report 2000-191 (2000)

A Ten-Year Assessment of Lobster Mini-Season Trends in Biscayne National Park, 2002-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/BISC/NRTR-2012/560 (Vanessa McDonough, March 2012)

Assessment of Natural Resource Condition Assessments In and Adjacent to Biscayne National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/BISC/NRR-2012/598 (Peter W. Harlem, Joseph N. Boyer, Henry O. Briceño, James W. Fourqurean, Piero R. Gardinali, Rudolph Jaffé John F. Meeder and Michael S. Ross, December 2012)

Biscayne National Monument: A Proposal (1966)

Baseline Ambient Sound Levels in Biscayne National Park (Cynthia Lee and John MacDonald, November 2012)

Biscayne National Park Colonial Nesting Bird Monitoring: Protocol Narrative—Version 1.1 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SFCN/NRR-2022/2343 (Robert Muxo, Kevin R.T. Whelan, Raul Urgelles, Joaquin Alonso, Judd M. Patterson and Andrea J. Atkinson, January 2022)

Biscayne National Park Lionfish Facts Brochure (2010)

Biscayne National Park: The History of a Unique Park on the "Edge" — An Administrative History (Leslie Kemp Poole, 2021)

Chemical Pollutants and Toxic Effects on Benthic Organisms, Biscayne Bay: A Pilot Study Preceding Florida Everglades Restoration USGS Open-File Report 2002-308 (2002)

Coastal Hazards & Climate Change Asset Vulnerability Assessment Protocol, Biscayne National Park (BISC) (Western Carolina University, September 2015)

Colonial Birds in South Florida National Parks, 1977-1978 Report T-538 (Oron L. Bass, Jr., April 1979)

Colonial Nesting Birds in Biscayne National Park: 2016-2017 Nesting Year Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SFCN/NRDS-2021/1332 (Robert Muxo, Kevin R.T. Whelan and Andrea J. Atkinson, November 2021)

Colonial Nesting Birds in Biscayne National Park: 2018-2019 Nesting Year Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SFCN/NRDS-2020/1286 (Robert Muxo and Kevin R.T. Whelan, July 2020)

Colonial Nesting Birds in Biscayne National Park: 2018-2019 Nesting Year Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SFCN/NRDS-2020/1286 (Robert Muxo and Kevin R.T. Whelan, July 2020)

Colonial Nesting Birds in Biscayne National Park: 2021-2022 Nesting Year Summary NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/184 (Robert Muxo and Kevin R.T. Whelan, September 2024)

Coral Reef Restoration Plan/Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, Biscayne National Park (March 2011)

Coral Reefs in the U.S. National Parks: A Snapshot of Status and Trends in Eight Parks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/NRR-2009/091 (Nash C. V. Doan, K. Kageyama, A. Atkinson, A. Davis, J. Miller, J. Patterson, M. Patterson, B. Ruttenberg, R. Waara, L. Basch, S. Beavers, E. Brown, P. Brown, M. Capone, P. Craig, T. Jones and G. Kudray, April 2009)

Creating Stewardship through Discovery: A Comparison among Visitors that Participated in three National Park / National Geographic BioBlitzes NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/BRD/NRR—2016/1270 (Gerard T. Kyle, Jee In Yoon, Carena J. van Riper and Jinhee Jun, August 2016)

Creating Stewardship through Discovery: Visitor Participation in the Biscayne National Park / National Geographic BioBlitz NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/BISC/NRR—2016/1268 (Gerard T. Kyle, Jee In Yoon, Carena J. van Riper and Jinhee Jun, August 2016)

Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Biscayne National Monument, Florida (August 2011)

Ecological & Hydrologic Targets for Western Biscayne National Park Resource Evaluation Report SFNRC Technical Series 2006:1 (2006)

Ecological Targets for Western Biscayne National Park Resource Evaluation Report SFNRC Technical Series 2006:2 (2006)

Ecosystem History of Southern and Central Biscayne Bay: Summary Report on Sediment Core Analyses U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2003-375 (G.L. Wingard, T.M. Cronin, G.S. Dwyer, S.E. Ishman, D.A. Willard, C.W. Holmes, C.E. Bernhardt, C.P. Williams, M.E. Marot, J.B. Murray, R.G. Stamm, J.H. Murray and C. Budet, September 15, 2003)

Ecosystem History of Southern and Central Biscayne Bay: Summary Report on Sediment Core Analyses — Year Two U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 2004-1312 (G. Lynn Wingard, Thomas M. Cronin, Charles W. Holmes, Debra A. Willard, Gary Dwyer, Scott E. Ishman, William Orem, Christopher P. Williams, Jessica Albietz, Christopher E. Bernhardt, Carlos A. Budet, Bryan Landacre, Terry Lerch, Marci Marot and Ruth E. Ortiz, October 4, 2004)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Biscayne National Park (EDAW Inc., May 2003, printed October 2006)

Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement: Volume 1, Biscayne National Monument, Florida (April 2015)

Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement: Volume 2, Biscayne National Monument, Florida (April 2015)

Fishery Management Analyses for the Reef Fish in Biscayne National Park: Bag and Size Limit Alternatives NPS Technical Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR-2007/064 (Jerald S. Ault, Steven G. Smith and James T. Tilmant, October 2007)

Florida Coral Reefs: Islandia (Bureau of Outdoor Recreation and National Park Service, 1965)

Foundation Document, Biscayne National Park, Florida (August 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, Biscayne National Park, Florida (August 2018)

General Management Plan / Development Concept Plan / Wilderness Study: Summary, Biscayne National Park, Florida (January 1983)

General Management Plan / Final Environmental Statement, Biscayne National Monument, Florida (September 1978)

Historic Resource Study: Biscayne National Park (Jennifer Brown Leynes and David Cullison, January 1998)

Historic Structure Report and Cultural Landscape Inventory for Boca Chita Key Historic District, Biscayne National Park (The Jaeger Company and Quinn Evans Architects, December 2010)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Biscayne National Park, 2001 (Daniel J. Stynes and Ya-Yen Sun, January 2003)

Jim Crow at the Beach: A Oral and Archival History of the Segregated Post at Homestead Bayfront Park (Iyshia Lowman, December 2012)

Joven Guardaparque (Spanish), Biscayne National Park/Big Cypress National Preserve/Everglades National Park (2007; solo para fines de referencia)

Junior Ranger, Biscayne National Park/Big Cypress National Preserve/Everglades National Park (2013; for reference purposes only)

Length-based risk analysis of management options for the southern Florida USA multispecies coral reef fish fishery (Jerald S. Ault, Steven G. Smith, Matthew W. Johnson, Laura Jay W. Grove, James A. Bohnsack, Gerard T. DiNardo, Caroline McLaughlin, Nelson M. Ehrhardt, Vanessa McDonough, Michael P. Seki, Steven L. Miller, Jiangang Luo, Jeremiah Blondeau, Michael P. Crosby, Glenn Simpson, Mark E. Monaco, Clayton G. Pollock, Michael W. Feeley, Alejandro Acosta, extract from Fisheries Research, Vol. 249, February 9, 2022)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Boca Chita Key Historic District (David Cullison and Jennifer Brown Leynes, May 30, 1997)

Offshore Reefs Archeological District (Lindsay C.M. Beditz, March 21, 1980)

Sweeting Homestead (Sweeting Plantation) (Peg Niemiec and Barbara E. Mattick, July 1997)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment: Biscayne National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/BISC//NRR-2022/2252 (David R. Bryan, Jiangang Luo and Jerald S. Ault, February 2022)

Park Newspaper (Pa-Hay-Okee): Winter 1987

Park Newspaper (A Visitor's Guide to the National Parks and Preserves of South Florida): 1998-1999

Park Stories/Parks Guide: 2003-2004 • 2004-2005 • 2005-2006

Satellite tracking reveals use of Biscayne National Park by sea turtles tagged in multiple locations (Kristen M. Hart, Allison M. Benscoter, Haley M. Turner, Michael S. Cherkiss, Andrew G. Crowder, Jacquelyn C. Guzy, David C. Roche, Chris R. Sasso, Glenn D. Goodwin and Derek A. Burkholder, extract from Regional Studies in Marine Science, Vol. 65, 2023)

Soundscape Preservation and Noise Management Plan for Biscayne National Park Draft (J.H. Lynch, December 1, 1999)

Supplemental Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Biscayne National Monument, Florida (November 2013)

Ti Gad Pak (Creole), Biscayne National Park/Big Cypress National Preserve/Everglades National Park (2007; for reference purposes only)

Trip Planner: 2003-2004 • 2004-2005 • 2005-2006 •2006-2007 • 2007-2008 • 2007-2008: Spanish edition • 2012

bisc/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025