|

CABRILLO

The Guns of San Diego Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 7:

WORLD WAR II AND AFTER, 1941-1948

On the first anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Fort Rosecrans' newspaper, Cannon Report, asked its readers, "Where Were You on Dec. 7th?" It replied to its own question:

Ft. Rosecrans was a hotbed of excitement. Furloughs were literally snatched away from men as they were leaving the gate. Soldiers out on passes rushed back as they never rushed before. Five men reported a Japanese submarine off Point Loma. Cpl. Don Whitehead, then on duty at headquarters, reflects: "The mass of telegrams, telephone calls and messages to man the guns gave me the most thrilling experiences yet. A day I'll never forget." [1]

When Japanese planes bombed Oahu, the Harbor Defenses of San Diego went on full alert. Troops moved to the gun positions immediately. Soldiers hauled ammunition to the coastal guns. Machine guns were set up. Guards prohibited citizens from entering the reservation, thus isolating Cabrillo National Monument. Batteries H and I, 19th Coast Artillery, set up 30 caliber machine guns for the antiaircraft protection of the Consolidated Aircraft Company. The Harbor Defense Command Post and the Harbor Entrance Control Post were manned immediately and continuously until the end of the war. Battery Point Loma replaced Battery McGrath as the alert/examination battery. [2]

A. Battery Ashburn

In November 1941, the Chief of Engineers received funds for the construction of a 16-inch gun battery at Fort Rosecrans. These two guns, the largest type in the harbor defenses of the United States, were the only ones in San Diego's defenses to be casemated. Known first as Battery Construction No. 126, it was named in honor of Maj. Gen. Thomas Quinn Ashburn, who graduated from West Point in 1897 and began his army career in the Artillery. He won a Silver Star in the Philippines and a Purple Heart in France. General Ashburn died in 1941.

The Macco Construction Company began work on the battery in June 1942 and completed it in March 1944 at a cost of $1,324,000. The guns were proof-fired in July, but the gun shields did not arrive until early 1945. The data concerning the guns and the barbette carriages were as follows:

| Guns | Caliber | Length | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer | Mounted |

| 1 | 16-inch | 816 in. | I | 71 | Bethlehem Steel | March 1944 |

| 2 | 16-inch | 816 in. | Mark II Model I | 97 | Watervliet Arsenal | March 1944 |

| Carriage Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 barbette | M-4 | 31 | Wellman Engineering Company |

| 2 barbette | M-4 | 39 | Watertown Arsenal |

Battery Ashburn served through the rest of the war but was declared surplus in May 1948, with the advent of atomic bombs and missiles. [3] Ashburn's plotting and switchboard room (PSR) was built as a large underground concrete structure to the north and east across the road from the battery.

|

| One of Battery Ashburn's two 16-inch guns. This photo must have been taken after World War II. The army would not have allowed such a picture during the war. Courtesy, historic photo collection, Cabrillo National Monument. |

|

| Battery 134, currently located near Navy antennae field, Imperial Beach and called Battery 99. The proposed name was Battery Gatchell. Work project was canceled in 1944, the 16-inch guns never installed. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy. |

B. Battery Humphreys

Work began on the first of three 6-inch batteries, Construction No. 238, later named Humphreys, in February 1942. V. R. Dennis of San Diego won the contract in the amount of $128,000 (actual cost, $200,000). Located on top of Point Loma above the new lighthouse, it was named in honor of Capt. Charles Humphreys, Fort Rosecrans' first commanding officer. The engineers considered the battery completed on October 14, 1943. A completion report recorded the guns and carriages thus:

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 6-inch | M1903A2 | 1 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| 2 | 6-inch | M1903A2 | 101 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | barbette | barbette | 101 | Wellman Engineering Company |

| 2 | barbette | barbette | 100 | Wellman Engineering Company |

C. Batteries Gillespie and Zeilin

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Army allowed the Marines to emplace two gun batteries in northwest Fort Rosecrans for training purposes:

Battery Gillespie, three 5-inch navy guns, and Battery Zeilin, two 7-inch navy guns. Both batteries were named for Marine Corps officers who took part in the American conquest of California: Lt. Archibald H. Gillespie, who came to Kearny's assistance following the Battle of San Pasqual, and Lt. Jacob Zeilin who later became commandant of the Corps. Soon after December 7, the Marines turned both batteries over to the Army and soldiers manned them on a twenty-four hour basis. Col. Ottosen expected to keep the guns as long as the Marines did not require them. The colonel reported that Battery Gillespie, along with Battery Point Loma, had an antisubmarine mission. [5] A 155mm battery was manned by HDSD troops for several months after the beginning of the war at Camp Callan Coast Artillery Replacement Training Center south of Torrey Pines State Park.

D. Batteries Grant and Woodward, and Fort

Emory

Engineers began work on Battery Construction No. 239 (Grant) in June 1942, the contractor being Herbert Mayson. This 6-inch, two-gun battery was located at Coronado Heights, along with Battery Imperial. A 16-inch gun battery was also scheduled for this area. In view of the concentration of defenses there, the San Diego Chamber of Commerce asked Secretary of War Henry L. Stinson to name it Fort Emory, in honor of Brig. Gen. William H. Emory. Emory had arrived in San Diego in 1846 with the Kearny command to survey the new international boundary. The Chamber of Commerce believed that it was due to Emory's representations that the boundary was placed south of San Diego Bay. The War Department agreed and in December so renamed the Coronado Heights Military Reservation as Fort Emory which became a sub-post of Fort Rosecrans.

Battery Grant itself was completed in April 1943, but the guns did not arrive until December. Meanwhile, the District Engineer gave the Coast Artillery permission to store 6-inch projectiles and powder in its magazines. Construction of the project cost $219,000. The identifications of its guns and carriages were thus:

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 6-inch | 1905 | 24 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| 2 | 6-inch | M-1905 | 20 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | barbette | barbette | 56 | York Corporation |

| 2 | barbette | barbette | 57 | York Corporation [6] |

Battery Woodward, Construction No. 237, was the last of the 6-inch batteries to be commenced, in March 1943, and the Army Engineers did not transfer it to the troops until August 1944. Its cost amounted to $256,000. Located in northwest Fort Rosecrans, its two guns replaced the Marine batteries Gillespie and Zeilin. It was named for Col. Charles G. Woodward who as a captain had commanded Fort Rosecrans from March 1906 to June 1907. The guns and carriages were identified as follows:

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 6-inch | 1903A-2 | 40 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| 2 | 6-inch | 1903A-2 | 55 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | barbette | barbette | 103 | Watertown Arsenal |

| 2 | barbette | barbette | 109 | Watertown Arsenal [7] |

|

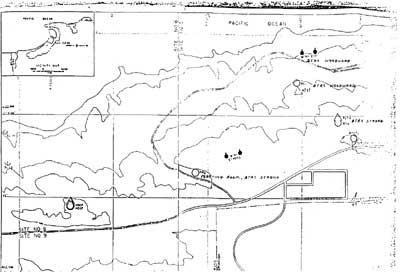

| Fort Emory, north of Imperial Beach, San Diego County. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

|

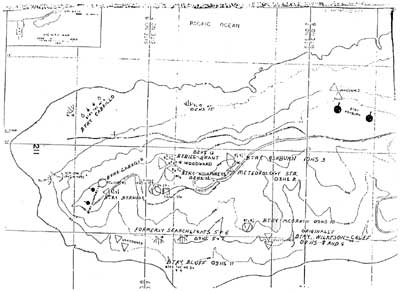

| Battery Grant, Fort Emory, two 6-inch guns. National Archives, RG 77, OCE, Box 129, File 600.914, Harbor Defenses of San Diego. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

E. Batteries Cabrillo, Fetterman (II), and Cortez

By the fall of 1942, the Army decided to install 90mm anti-motor torpedo boat (AMTB) batteries in the harbor defenses. Each battery consisted of two fixed guns and two mobile guns. (The mobile guns were kept in storage until an emergency occurred.) The mission of these batteries was to attack enemy motor torpedo boats, to defend against enemy landings, to assist against enemy air (the 33rd Coast Artillery (AA), which was not in the Harbor Defenses of San Diego, was primarily responsible against enemy air attacks), and to attack enemy submarines within range. After considerable discussion, the Office of the Chief of Engineers decided that San Diego would receive three four-gun 90mm batteries: Battery Cabrillo at Point Loma, which meant the inactivation of Battery Point Loma's 155mm guns; Battery Fetterman at Ballast Point; and Battery Cortez on the Silver Strand. Two guns would be emplaced and two mobile.

All three batteries were completed in August 1943 and the six guns were mounted in September. The District Engineer supervised construction of concrete emplacements. The post engineer installed the electricity and the troops performed the necessary labor. The cost of each battery was approximately $20,000.

Battery Cabrillo

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 3031 | Wheland Company |

| 2 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 15327 | General Motors, Chevrolet Division |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-92 | General Motors, Fisher Body |

| 2 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-201 | General Motors, Fisher Body |

Battery Fetterman

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 15329 | General Motors, Chevrolet |

| 2 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 10806 | Watervliet Arsenal |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-160 | General Motors, Fisher Body |

| 2 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-235 | General Motors, Fisher Body |

Battery Cortez

| Guns | Caliber | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 15311 | General Motors, Chevrolet |

| 2 | 90mm | M1-1943 | 14861 | General Motors, Chevrolet |

| Carriages | Type | Model | Ser. No. | Manufacturer |

| 1 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-205 | General Motors, Fisher |

| 2 | M-3 | PA1943ABO | T3-156 | General Motors, Fisher [8] |

F. Additional Defense Measures

To supplement the new 90mm batteries, the Army installed three batteries of 37mm antiaircraft weapons, sited primarily to protect the harbor entrance against motor torpedo boats. Each battery consisted of two 37mm guns with two .50 caliber machine guns mounted on each 37mm carriage: Battery Cliff, immediately above the new lighthouse; Battery Bluff, at Billy Goat Point; and Battery Channel, also on the east side of Fort Rosecrans on Ballast Point adjacent to the U.S. Coast Guard station. Battery Bluff is within Cabrillo National Monument and is recorded as Historic Structure 9. In 1944, the Western Defense Command announced that 40mm antiaircraft guns would replace all 37mm weapons in the command. Although sixteen 40mm guns were authorized, as far as it may be determined the war ended before any of them reached San Diego. [9]

|

| AMTB (Anti-Motor Torpedo Boat), Battery Bluff. Position currently located at Cabrillo National Monument. This battery consisted of two water-cooled 50 caliber machine guns and one 37mm cannon. Three men on right can be seen feeding belts and clips to weapons. Photo courtesy of San Diego Military Heritage Society. |

In January 1943 the Los Angeles District Engineer learned that the cast armor shields for the guns of 6-inch Battery Humphreys were en route to Fort Rosecrans. Each shield weighed forty-two tons. Ironically, the shields for the 8-inch guns of Battery Strong still had not been installed as late as July 1945. The question remains as to whether they ever did arrive. [10]

Early in 1942, Col. Ottosen complained that the harbor defense command post was too small for efficient operations, especially for the army and navy radios which had to compete with other activities going on in the same room. Also, the structure needed latrines. He said that the signal station in the old lighthouse was reasonably satisfactory, but not as a permanent installation. As a result of his letter, a radio room was added to the HDCP and a concrete dugout signal station was constructed south of the lighthouse. Another enlargement of the command post occurred in 1943 after Gen. DeWitt, commanding the Western Defense Command, paid a visit to San Diego. At the HDCP he was unhappy in that there was no room wherein senior Army and Navy officers could hold private conferences. The Chief of Engineers promptly made $11,600 available for the additional bombproof room. [11]

Coastal radar, SCR296A, was added to the harbor defenses early in 1943. The first three sets were erected near Battery Strong in north Fort Rosecrans, near the new lighthouse at Point Loma, and near the Mexican border. Before the year was out, three additional sets were authorized: La Jolla, Fort Rosecrans, and Fort Emory. [12]

G. Fire Control Stations

The base-end stations built during the war for the new batteries had either one or two levels, were constructed of concrete, and usually had steel roofs. Unlike the older stations, they were camouflaged with rocks cemented on their roofs. The two-level stations had an extra room at the rear of the lower level. Observers often used this room as sleeping quarters although it was not authorized as such. Although the designations of these stations may seem bewildering at first glance, there was logic to the numbering system, for example, B5/3 S5/3. The batteries at San Diego were listed in a tactical order. The lower number "3" indicates that this is a base-end station for the battery that had the tactical number 3, which was Battery Ashburn. The upper number "5" indicates that this was Battery Ashburn's fifth base-end station.

By July 1945 these stations ranged from Solana Beach (Santa Fe) in the north to the Mexican border:

| *Solana Beach (Santa Fe) | B5/3 S5/3** | Battery Ashburn | |

| Soledad Mountain | B3/3 S3/3 | Battery Ashburn | 2-level |

| B5/9 S5/9 | deferred 16-inch battery | ||

| La Jolla (Hermosa) | B5/1 S5/1 | Battery Woodward | |

| B5/2 S5/2 | Battery Strong | 2-level | |

| B5/5 S5/5 | Battery Humphreys | ||

| West Point Loma (Sunset) | B1/1 S1/1 | Battery Woodward | 2-level |

| B2/3 S2/3 | Battery Ashburn | ||

| B4/2 S4/2 | Battery Strong | 2-level | |

| B2/5 S2/5 | Battery Humphreys | ||

| B4/9 S4/9 | deferred 16-inch battery | 2-level | |

| B5/10 S5/10 | Battery Grant | ||

| *North Fort Rosecrans | BC2 | Battery Commander, Battery Strong | 2-level |

| B1/2 S1/2 | Battery Strong | ||

| BC1 | Battery Commander, Battery Woodward | ||

| B3/1 S3/1 | Battery Woodward | ||

| *South Fort Rosecrans (Cabrillo) | BC3 | Battery Commander, Battery Ashburn | 2-level |

| B1/3 S1/3 | Battery Ashburn | ||

| B2/1 S2/1 | Battery Woodward | 2-level | |

| B4/10 S4/10 | Battery Grant | ||

| BC5 | Battery Commander, Battery Humphreys | ||

| B1/5 S1/5 | Battery Humphreys | ||

| BC6 B1/6 | Battery Commander, Battery McGrath | ||

| (Loma) | BC4 | Battery Commander, Battery Cabrillo | |

| B2/2 S2/2 | Battery Strong | ||

| East Fort Rosecrans | BC7 | Battery Commander, Battery Fetterman (II) | |

| Coronado Beach M.R. (Strand) | B3/2 S3/2 | Battery Strong | |

| B3/5 S3/5 | Battery Humphreys | 2-level tower | |

| B3/9 S3/9 | deferred 16-inch battery | ||

| B3/10 S3/10 | Battery Grant | 2-level tower | |

| BC8 | Battery Commander, Battery Cortez--not built | ||

| Coronado Heights M.R. (Fort Emory) | BC9 | Battery Commander, deferred 16-inch | |

| B1/9 S1/9 | deferred 16-inch battery | 2-level tower | |

| BC10 | Battery Commander, Battery Grant | ||

| B1/10 S1/10 | Battery Grant | 2-level tower | |

| *Mexican border | B4/1 S4/1 | Battery Woodward | |

| B4/5 S4/5 | Battery Humphreys | 2-level | |

| B4/3 S4/3 | Battery Ashburn | ||

| B2/10 S2/10 | Battery Grant | 2-level | |

| B2/9 S2/9 | deferred 16-inch battery | ||

| B6/2 S6/2 | Battery Strong |

* Extant 1990. ** B5/3 S5/3 shifted from Mexican border to Solana Beach (Santa Fe) along with other redesignations later in the war. B=target azimuth station. S=shot/splash azimuth station.

Additional fire control stations included the combination HDCP-HECP, Battalion One Command Post (CP), Battalion Two CP, meteorological station (former army radio building), and fire control switchboard, all at Fort Rosecrans. A fort command post and Battalion Three CP at Fort Emory were planned but not built. [13] Battalions had replaced the former Groups by 1945.

By 1943 several of the older fire control stations were unassigned, their batteries having been abandoned. Among then were the base-end stations for Battery Calef-Wilkeson (HS8 and HS9) that are within the boundaries of Cabrillo National Monument. Three of the two-level, dug-in stations built during the war are also within the monument: BC3-B1/3 S1/3, (HS3) the battery commander's station and a base-end station for 16-inch Battery Ashburn northwest of the old lighthouse and above the army radio station; BC5, B1/5 S1/5, (HS12) the battery commander's station and a base-end station for Battery Humphreys, the higher of the stations below the Whale Overlook; and B2/1 S2/1 — B4/10 S4/10, (HS13) the upper level was a base-end station for Battery Woodward and the lower was a base-end station for Battery Grant; this is the lower station below the Whale Overlook. The older base-end station below the Cabrillo Statue, HS10, was assigned to Battery McGrath as BC6 B1/6.

|

| Battalion 2 command post facing westward over ocean. Located on Naval Ocean Systems Center property. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

|

| Battalion 1 command post, located south of Old Point Loma Lighthouse on Naval Ocean Systems property. Photo courtesy of George R. Schneider. |

H. Wartime Events [14]

On December 8, 1941, the President of Mexico gave permission for a U.S. Army detachment to enter Baja California to survey the country to determine any enemy activity and to select sites for the installation of aircraft detectors. The first detachment, under Capt. Albert P. Ebright, 11th Cavalry, was stopped at the border by the Mexican Army, the local general not having been informed of the permit. The soldiers returned to Fort Rosecrans. Later a detail of American officers was allowed to enter the country, but Mexico demanded that they be in civilian clothing and unarmed. By the summer of 1942, the United States had erected three radar stations in Baja California: at Punta Salispuedes, twenty miles northwest of Ensenada; Punta San Jacinto, 125 miles south of Ensenada; and Punta Diggs on the northeast coast of the peninsula. American personnel operated the stations at first and taught Mexican soldiers how to operate them. In August 1942 the Mexican Army took over the operations under the provisions of lend-lease. [15]

Throughout the war three organizations composed the Harbor Defenses of San Diego: Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, HDSD; the 19th Coast Artillery Regiment (HD), and the 166th Station Hospital (250 beds). The 19th CA Regiment consisted of a headquarters battery, searchlight battery, and three battalions, each with a headquarters battery and three lettered companies. In addition the 141st Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop was attached to Fort Rosecrans. Elsewhere in the San Diego area a large number of army units, including the 140th and 125th Infantry Regiments, the 33rd Coast Artillery Brigade (AA), and the 770th Military Police Battalion, maintained guard. All these units were under the command of the Southern California Sector which was activated December 8, 1941, under the leadership of Maj. Gen. Joseph Stillwell. During the war the U.S. Navy had fifteen activities at San Diego, including the Naval Repair Base, Destroyer Base, Naval Air Station on North Island, Naval Training Station, Naval Supply Depot, Naval Amphibious Base at Coronado, and naval hospitals.

Between 1941 and 1945 Harbor Defenses experienced sixty-one reports of enemy submarines, unidentified surface vessels, and underwater contacts. In the two years 1942 and 1943, ships and planes went into action twenty-eight times because of these reports. During 1943 alone, 115 depth charges were dropped off San Diego. Later studies, however, have not confirmed any Japanese submarine activity in the vicinity of San Diego.

Three military units were activated at Fort Rosecrans in 1942 and 1943. The 262nd Coast Artillery Battalion, consisting of a headquarters battery and two lettered companies, organized in May 1942 and departed for duty in Alaska in November where the Japanese had occupied Attu and Kiska. Black soldiers formed the second unit, the 77th Chemical Smoke Generator Company in April 1942. This outfit remained in San Diego where it established the smoke generator defense of the area. The third outfit, the 281st CA Battalion, was at Fort Rosecrans from February to May 1943, when it departed for the South Pacific.

In May 1942 the United States learned that Japan had prepared plans for attacks on Midway and Alaska. The War Department anticipated that the Japanese would carry out hit-and-run attacks on West Coast cities at the same time. The Pentagon rushed all possible aid to the coast. Gen. George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, paid a visit to San Diego on May 23-24. The attacks did not come. Japan suffered a major defeat at Midway early in June. This was the turning point in the Pacific War, but the harbor defenses remained on guard until Japan surrendered. [16]

The death blow finally came to Fort Rosecrans' first Endicott battery, Calef-Wilkeson, in the fall of 1942 when orders came to salvage the guns and carriages. Along with these 10-inch guns, the mortars of Batteries John White and Whistler were declared obsolete. The fort's adjutant figured out the amount of metal in tons that salvaging would yield:

| John White | Whistler | Calef-Wilkeson | |

| Lead | -- | -- | 140 |

| Cast iron | 120 | 120 | 480 |

| Brass & bronze | 3/4 | 3/4 | 2 |

| Steel | 88 | 88 | 400 [17] |

The Army allowed Superintendent John R. White, of Sequoia National Park, to visit Cabrillo National Monument in 1943. He was not pleased with what he saw. The lighthouse had been painted in camouflage colors and was still being used as part of the signal station. The Army had erected a wooden signal tower on the parking lot south of the tower. The superintendent also caught sight of either one of the concrete fire control stations below the later Whale Overlook or the new concrete signal station south of the parking lot. But the Army would continue to have control of the monument for three more years. [18]

The only serious accident during the war in the harbor defenses occurred on January 29, 1944. A defective fuse in a 6-inch, high-explosive projectile caused a premature detonation at Battery Humphreys. Five soldiers were killed and seven were wounded. Both the tube and the cradle were destroyed and several months passed before a replacement gun arrived.

Starting in January 1944, the number of troops assigned to the San Diego area began to decline. Col. Ottosen, besides commanding the harbor defenses, took over command of the Army's San Diego Sub-Sector and moved its headquarters along with the 115th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron to Fort Rosecrans. In June the cavalry transferred to Louisiana, the sub-sector was deactivated, and two platoons of the 141st Cavalry Troop were attached to the harbor defenses.

During 1944 a number of tank and antiaircraft battalions garrisoned the fort while they trained in amphibious landings for operations in the Pacific. The 19th CA Regiment was deactivated that fall, the 1st Battalion becoming the 19th CA Battalion (HD), and the 2nd Battalion, the 523rd CA Battalion (HD). The downgrading of the harbor defenses speeded up in 1945. Most of the personnel transferred overseas. The Harbor Defense Command Post ceased operations in August, two days before Japan's surrender. In September the two harbor defense battalions were deactivated and the garrison now consisted of a headquarters battery and four lettered batteries. Both the Army and the Navy discontinued their activities at the Harbor Entrance Control Post that same month. The twenty-four-hour alert for almost fifty months had come to an end.

I. A Final Look at the Defenses

Army Engineers prepared a "supplement" to the harbor defense project for San Diego and forwarded it to Washington in April 1946, where notations were made on it as late as 1948. Only a few extracts from the supplement are included herein inasmuch as the era of traditional coastal defense was quickly passing into history. [19]

The "Groups" had given way to "Battalion" command posts. Battalion CP1 controlled those elements charged with the defense of the channel entrance to San Diego Bay, that is, the AMTB batteries. Battalion CP2 controlled those elements that could attack enemy naval forces approaching from the north. Battalion CP3, located at Fort Emory, was to have controlled the weapons that could attack an enemy approaching from the south. It was not built. The tactical numbers of the batteries had changed due to the inclusion of the AMTB weapons:

| Tactical number | Guns |

| 1. Battery Woodward | 2 6-inch |

| 2. Battery Strong | 2 8-inch |

| 3. Battery Ashburn | 2 16-inch |

| 4. Battery Cabrillo | 2 90mm plus 2 mobile 90mm |

| 5. Batteries Humphreys and Bluff | 2 6-inch and 2 37mm |

| 6. Battery McGrath | 2 3-inch |

| 7. Battery Fetterman (II) | 2 90mm plus 2 mobile 90mm |

| 8. Battery Cortez | 2 90mm plus 2 mobile 90mm |

| 9. deferred 16-inch battery | - |

| 10. Battery Grant | 2 6-inch |

An interesting note said that all the cantonment buildings at Fort Emory were constructed as small one- or two-family cottages and were arranged to give the appearance of a defense housing project. The buildings were painted in pastel colors and the roofs were colored red, blue, and green. Lawns, shrubbery, stone walks, and trees heightened the effect.

Notations on the supplement marked the end of the guns of San Diego. Battery Strong's 8-inch guns were eliminated by War Department approval in 1947. Ashburn's 16-inch guns followed in 1948, as did McGrath's 3-inch guns. The record is silent about the 6-inch batteries Woodward, Humphreys, and Grant, but, before long, their weapons had gone to gun heaven too. The harbor defenses of San Diego were no more.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cabr/guns-san-diego/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2005