|

Cabrillo National Monument California |

|

NPS photo | |

Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo is as mysterious as the waters he explored. While much is unknown, we are certain about this: Cabrillo was the first European to set foot on the west coast of what is now the United States. His expedition brought Spain's first great era of exploration to a close.

Cabrillo set out on his epic voyage of exploration 50 years after Columbus landed in America. Commanding three vessels, he sailed north from Mexico into unknown waters. He was to claim land for the king of Spain and the viceroy of New Spain, discover a route to Asia and the Spice Islands, search the uncharted coast for a mythical passage that connected the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and search for gold.

No one knows for certain where Cabrillo was born or where he is buried. The 16th-century historian, Antonio de Herrera, described him as Portuguese. Cabrillo's original navigational log has been lost, and details of his voyage and the circumstances of his death come from a summary account that was compiled after the expedition had returned to Mexico.

Cabrillo arrived in the Americas by 1520. He gained prominence as a crossbowman during the Hernán Cortés conquest of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán, now Mexico City. Later, he joined Pedro de Alvarado to conquer and settle Guatemala. Ambitious and well educated, Cabrillo became a wealthy landowner and a shipbuilder. After Alvarado died in a native uprising, Antonio de Mendoza, the viceroy of New Spain, gave Cabrillo command of the vessels San Salvador, Victoria, and San Miguel. On June 27, 1542, sponsored by Antonio de Mendoza, Cabrillo and his crew sailed north from Navidad to "discover the coast of New Spain."

Un puerto cerrado y muy bueno

On September 28, 1542, Cabrillo's flotilla entered a harbor that he described as

"a closed and very good port." Coastal sage scrub covered the hills and valleys.

He stepped ashore on a silvery strand of beach and named the area San Miguel,

the site of modern San Diego. Cabrillo stayed in San Miguel six days to wait out

a storm, then resumed his voyage up the coast. They sighted the islands of Santa

Catalina and San Clemente, which Cabrillo named San Salvador and Victoria, after

his vessels. A day later the expedition turned toward the mainland, into what is

now San Pedro Bay. The summary log recounts that the horizon was smoky. Cabrillo

named it Bahia de Los Fumos—Bay of Smokes—which is today's Los

Angeles.

Unsolved Mystery

In November, the expedition stopped for water on the island the Spaniards had

dubbed Isla de Posesión, one of the Channel Islands. Exactly what happened is a

mystery. One account says that Cabrillo, while rushing to aid his men during a

fight with Chumash Indians, jumped from a boat and broke his leg. Another

version notes that he had broken his arm near the shoulder on an earlier visit

to Posesión. Whatever happened, complications ensued—with fatal results. On

January 3, 1543, his goals of exploration unfulfilled, Cabrillo died.

Chief pilot Bartolomé Ferrer took command and, heeding Cabrillo's wishes to discover more coastland, headed north. How far they got is unclear, but they may have reached the Rogue River area in Oregon. In March Victoria disappeared in a storm. Reunited after three weeks, Ferrer and the crew abandoned the expedition, returning to Navidad on April 14, 1543. The expedition claimed more than 800 miles of coastline for Spain. It did not find a route to the Spice Islands, the mythical passage, or gold. What Cabrillo did accomplish had long lasting importance. His voyage added knowledge of landmarks, winds, and currents that made further exploration safer. Because of this, a west-to-east crossing of the Pacific 22 years later established trade routes between New Spain and the Philippines, paving the way for the Manila galleons. The Spanish age of exploration gave way to the Colonial era.

Kumeyaay Indians

As Cabrillo sailed north he knew that the land he was to claim for Spain was already occupied by people called Indians. When he entered this harbor he saw several Kumeyaay Indians waiting on shore. They had long hair, some in braids and adorned with feathers or shells. Some men wore capes made from the skin of sea otter, seal, or deer. By mimicking men with lances on horseback and painting themselves to show armor and the slashed sleeves worn by Spanish soldiers, the Kumeyaay indicated that other Spanish were several days' journey inland and that they had killed many Indians. Cabrillo, however, gave the Kumeyaay gifts and said he would not harm them. He noted they looked prosperous and sailed far out to sea fishing in reed canoes. The Kumeyaay, shown here in an 1857 engraving, lived well by understanding their environment. They made pottery, baskets, and abalone and other shell jewelry that they traded to neighbors.

Exploring Cabrillo Today

Tidepools—Life on the Edge

Tides control the rhythm of life along the ocean's shore. Marine plants and animals living here in the rocky intertidal zone have adapted to harsh conditions of pounding surf, intermittent exposure to sun and drying wind, and sharp changes in temperature and salinity. Here are shore crabs, spongy dead man's fingers, bat stars, surf grass, sea hares, and other plants and animals.

Cabrillo National Monument preserves one of the last rocky intertidal areas open to the public in southern California. Survival of this marine habitat depends on the health of the surrounding ocean and land. Changes in one environment alters the other: polluted runoff, erosion and sediment buildup, and oil spills can destroy the tidepools.

Survival of the plants and animals in the rocky intertidal zone also depends on you. Please walk gently. To remove a plant or animal from its environment, or even move it from one side of a tidepool to the other, could kill it. All forms of life in tidepools are protected by federal law and should not be disturbed or removed.

Watching Gray Whales

Gray whales pass Point Loma during their annual roundtrip migration of 12,000 miles. They leave Arctic summer feeding grounds in September and travel to the bays of Baja California, where females bear calves. In the spring they head north; the cows with calves are last to leave the lagoons. The herd that passes here was so heavily hunted that by the 1920s only a few thousand remained. National appeals and protection by international treaties saved them from extinction. Now more than 25,000 gray whales migrate this route. The best viewing is during January and February. Watch for their spout, or blow, beyond the kelp beds. When a whale surfaces to breathe, it exhales a plume of air and water about 15 feet into the air.

Coastal Sage Scrub

The coastal sage scrub community on Point Loma represents one of the few remaining protected stands of this ecotype. This blend of aromatic sages, low-growing shrubs, succulents, flowers, and grasses was home for an abundance of mammals, birds, and reptiles. Today, more than 70 percent of this ecotype in southern California is gone. Over time, developers have turned this habitat into a kaleidoscope of roadways, tract and luxury homes, industrial parks, and malls. Hundreds of species of plants and animals of San Diego County are endangered, threatened, or extinct—it is the longest such list in the United States. The U.S. Navy, National Park Service, and other landowners on Point Loma have joined forces to save the coastal sage scrub. The Point Loma Ecological Reserve is a haven for plants and animals as diverse as peregrine falcon, side-blotched lizard, Anna's hummingbird, southern Pacific rattlesnake, and gray fox.

Defending the Harbor

Point Loma forms a natural protective barrier at the entrance of San Diego Bay. A sandstone rampart jutting into the sea, the peninsula rises 422 feet and provides strategic views of the harbor and ocean. In 1852 the United States government recognized this important landmark and designated the area as a military reserve. In 1899 the War Department dedicated Fort Rosecrans and, over the years, built a series of gun batteries. During World Wars I and II military facilities on the point provided vital coastal and harbor defense systems. Between 1918 and 1943, the Army built searchlight bunkers, fire control stations, and gun batteries. The largest guns were at Battery Ashburn, northwest of the park entrance, where two 16-inch guns could fire 2,300-pound shells nearly 30 miles out to sea. The military also painted the Old Point Loma Lighthouse olive green and used it as a command post and radio station.

Old Point Loma Lighthouse

The Old Point Loma Lighthouse is a reminder of different times: of sailing ships and oil lamps and the men and women who tended these isolated coastal lights. In 1851 the U.S. Coastal Survey selected this headland as the site for a navigational aid. The crest of the point stood 422 feet above sea level and overlooked the bay and the ocean. At the time it seemed like the ideal location.

Builders completed the house in 1854, and a year later installed a Fresnel lens—the best technology available. At dusk on November 15, 1855, the new keeper lit the oil lamp for the first time. In clear weather mariners could see its light 39 miles out to sea. For the next 36 years, except on foggy nights, it welcomed sailors to San Diego harbor.

But, the seemingly right location had concealed a serious flaw. Fog and low clouds often obscured the light. On March 23, 1891, the keeper, Robert Israel, extinguished the lamp for the last time. Boarding up the lighthouse, Israel, his wife, Maria, and their family moved into a new light station at the bottom of the hill.

About Your Visit

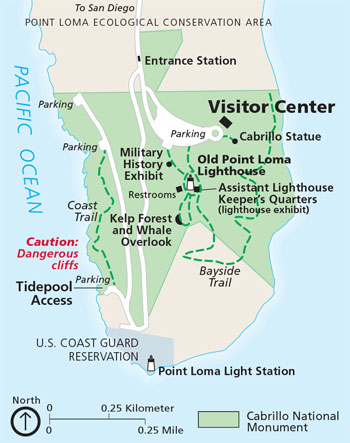

(click for larger map) |

Enjoying the Park

Visitor Center The best place to begin your visit to Cabrillo National Monument is at the visitor center. Here you will find information about the park, exhibits, films, and panoramic views of the harbor. A bookstore, which is operated by the Cabrillo National Monument Foundation, offers publications about the area's cultural and military history, its plants and animals, and Cabrillo and other explorers. The visitor center is open daily.

Seeing the Park The park is open for day use only. There is an entrance fee. It is an easy walk from the visitor center to the Cabrillo statue, the military history exhibit, Old Point Loma Lighthouse, and the whale overlook. To visit the tidepool area, drive to the park road and look for the signs. Self-guiding exhibits along walkways and overlooks explain the plants, animals, and history of the area. The park has no food service, but you are welcome to picnic on park benches.

Bayside Trail This trail (two miles round-trip) descends about 300 feet through native coastal sage scrub. It passes remnants of the defense system that protected the harbor during World Wars I and II. There are no restrooms. There is no access to the beach.

Accessible The visitor center, films, exhibits, whale overlook, and harbor overlooks are accessible to visitors with disabilities. A pass to drive to the lighthouse is available at the entrance station and at the visitor center.

For a Safe Visit

Please be alert and observe these precautions and regulations.

Cliffs The sandstone cliffs are extremely dangerous. Stay back from the edges—they can suddenly give way. Falls can be fatal.

Tidepools Rocks are slippery, and barnacles are sharp; wear sturdy non-slip shoes. Drive, do not walk, to the tidepool area. Collecting marine animals, shells, or rocks is prohibited by federal law.

Trails Stay on the trails to prevent erosion and to protect the sensitive vegetation.

Wild Animals Beware of rattlesnakes and biting animals. Do not put your hands or feet in places you cannot see. Do not feed the wildlife.

Pets Please leave pets at home. If you bring pets, they are allowed only in tidepool areas and must be on a leash at all times. Pets left in vehicles even for a short time may suffer from heat stroke and die.

Thefts Thefts can happen wherever you travel. Lock valuables out of sight or take them with you.

Protected Do not remove, collect, or damage any plants, animals, shells, or cultural artifacts in the park; all are protected by federal law. In an emergency call 911.

Getting Here The park is within the city of San Diego at the end of Point Loma.

Bus: Public buses make daily trips to the park.

Vehicle: • From southbound I-5 Rosecrans Street exit; turn right on Canon Street; turn left onto Catalina Blvd. • From northbound I-5 take Pacific Highway to Barnett, turn left on Rosecrans Street. • From westbound I-8 take Rosecrans Street exit; turn right on Cañon Street; turn left onto Catalina Blvd. Follow the signs to the park.

Source: NPS Brochure (2002)

|

Establishment Cabrillo National Monument — October 14, 1913 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Physical and Cultural Overview: The Cabrillo National Monument (James Robert Moriarty III, undated)

An Archaeological Survey of Cabrillo National Monument (Claude N. Warren, March 18, 1960)

An Embarrassment of Riches: Administrative History of Cabrillo National Monument (HTML edition) (Susan C. Lehmann, 1987)

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Cabrillo National Monument, California NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2006/355 (Diana L. Engle and John Largier, August 2006)

Coastal Hazards & Climate Change Asset Exposure Analysis & Case Study: Cliff Retreat Exposure for Cabrillo National Monument NPS 342/154057 (K. Peek, B. Tormey, H. Thompson, R. Young, S. Norton and R. Scavo, February 2017)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Cabrillo National Monument Visitor Center Historic District (2009)

Documenting the Paleontological Resources of National Park Service Areas of the Southern California Coast and Islands (Justin S. Tweet, Vincent L. Santucci and Tim Connors, extract from Monographs of the Western North American Naturalist, v7 n1, January 2014)

Ecological condition and public use of the Cabrillo National Monument intertidal zone 1990-1995 USGS Open-File Report 2000-98 (John M. Engle and Gary E. Davis, 2000)

Foundation Document, Cabrillo National Monument, California (February 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Cabrillo National Monument, California (January 2017)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Cabrillo National Monument NPS Natural Resources Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2018/1666 (Katie KellerLynn, June 2018)

Historic Furnishings Report, Point Loma Lighthouse, Cabrillo National Monument (Katherine B. Menz, December 1978)

Historic Structure Report for Harbor Defense Structures at Cabrillo National Monument (Carey & Co., Inc., April 15, 2000)

Historic Structure Report, The Old Point Loma Lighthouse, Cabrillo National Monument, San Diego, California (F. Ross Holland, Jr. and Henry G. Law, March 1981)

Just for Kids / Junior Ranger, Cabrillo National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Cabrillo National Monument (April 2009)

Monitoring of Terrestrial Reptiles & Amphibians by Pitfall Trapping in the Mediterranean Coast Network: Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area & Cabrillo National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/MEDN/NRTR—2006/005 (Gary Busteed, J. Lane Cameron, Seth Riley, Lena Lee, Andrea Compton, Eileen Berbeo and Tiffany Duffield, September 2006)

National Park Service Geologic Type Section Inventory, Mediterranean Coast Inventory & Monitoring Network NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MEDN/NRR-2021/2279 (Tim Henderson, Justin S. Tweet, Vincent L. Santucci and Tim Connors, July 2021)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Cabrillo National Monument (Jamie M. Donahoe, June 25, 1997)

Old Point Loma Lighthouse (Mary R. Bradford, 1974)

Natural History, Cabrillo National Monument (Howard B. Overton, 1989)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Cabrillo National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CABR//NRR-2019/1882 (Brian Hudgens, Kathryn McEachern, Jesica Abbot, Tonnie Cummings, Keith Lombardo, Melissa Harbert, Jared Duquette and Amon Armstrong, March 2019)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Cabrillo National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CABR//NRR-2020/2076 (Brian Hudgens, Jesica Abbot, Tonnie Cummings, Keith Lombardo, Melissa Harbert, Jared Duquette and Amon Armstrong, February 2020)

Park Newspaper (The Cabrillo Journal): Summer-Fall 2012 • Fall-Winter 2012 • Spring-Summer 2016 • Fall-Winter 2016

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Rocky Intertidal Monitoring Program at Cabrillo National Monument: 2020 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MEDN/NRDS-2021/1338 (Lauren L.M. Pandori, Brian C. Hong, Linh Anh Cat and Keith Lombardo, December 2021)

Rocky Intertidal Community Shift Over 30 Years: 1999-2020 Rocky Intertidal Long Term Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/MEDN/NRR-2031/2501 (Lauren L.M. Pandori, Lauren Strope and Linh Anh Cat, March 2023)

Shadows of the Past at Cabrillo National Monument (Roger E. Kelly and Ronald V. May, 2001)

Soil Survey of Cabrillo National Monument, California (2013)

State of the Park Report, Cabrillo National Monument, California State of the Park Series No. 2 (April 2013)

The 19th Coast Artillery and Fort Rosecrans: Remembrances (Howard B. Overton, comp. and ed., 1993)

The Distribution and Dynamics of Nighttime Lights in the Mediterranean Coast Network of Southern California: Cabrillo National Monument, Channel Islands National Park, Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MEDN/NRR—2016/1290 (Thomas W. Gillespie, Katherine S. Willis, Stacey Ostermann-Kelm, Olivia Jenkins, Felicia Federico, Travis Longcore, Lena Lee and Glen M. MacDonald, August 2016)

The Guns of San Diego: San Diego Harbor Defenses, 1796-1947 (Erwin N. Thompson, 1991)

The Origin and Development of Cabrillo National Monument (HTML edition) (F. Ross Holland, Jr., ©Cabrillo Historical Association, 1981)

Vegetation Classification of the Cabrillo National Monument and Point Loma Navy Base, San Diego Count, California (Anne Klein and Todd Keller-Wolf, September 15, 2010)

Cabrillo National Monument Aug 6, 2013 with Chloe Noelle (FOX 5)

cabr/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025