|

Canyon de Chelly National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

The Canyons

A red-tailed hawk floats high above the canyon, casting shadows on the sheer walls. A Navajo woman tends her corn on the canyon floor, surrounded by red cliffs that soar cathedral-like above her. A family at Spider Rock Overlook marvels at the 800-foot freestanding spire and the quilt of colors far below. Each has a different view. Yet for all, the canyon is quiet—its silence challenged only by a distant raven's call.

People have lived in these canyons for nearly 5,000 years—longer than anyone has lived uninterruptedly elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau. The first residents built no permanent homes, but remains of their campsites and images etched or painted on canyon walls tell us their stories. Later, people we call Basketmaker built compounds and storage, social, and ceremonial spaces high on the canyon's ledges. They lived in small groups, hunted game, grew corn and beans, and created wall paintings.

Ancestral Puebloan people followed. Predecessors of today's Pueblo and Hopi Indians, they are often called Anasazi, a Navajo word for ancient ones. They built the multistoried villages, small compounds, and kivas with decorated walls that dot the canyon alcoves and talus slopes.

About 700 years ago most people moved away, but a few remained in the canyons. Later, migrating Hopi and other tribes spent summers here, hunting and farming. Finally, at the end of a long journey, the Navajo arrived. They built homes, learned new crafts, and added their own designs to this ancient gallery's walls.

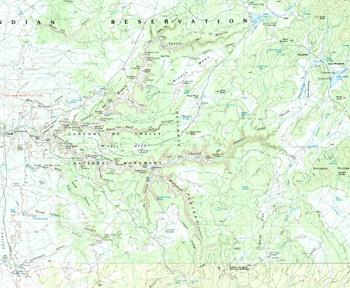

The labyrinth called Canyon de Chelly (d'SHAY) comprises several canyons that include Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto. At the canyons' mouth near Chinle, the rock walls are only 30 feet high. Deeper in the canyons the walls rise dramatically until they stand over 1,000 feet above the floor. Cliffs overshadow streams, cottonwoods, and small farms below. Across many millennia, water etched paths through layers of sandstone and igneous rock, as the Defiance Plateau rose. Today, the ancient peoples' open windows beckon us.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument was established in 1931 to preserve this record of human history. Embracing nearly 84,000 acres within the Navajo Reservation, the monument is administered by the National Park Service. But these canyons are home to Dine, the Navajo people.

People of the Canyon through Time

Approaches to the human history of Canyon de Chelly vary. Physical evidence—artifacts and written accounts—can be used to place humans in a timeline, a chronology that marks events on a calendar. But to the Navajo and many American Indians, the passage of linear time is not important. Native histories and the past are explained through traditional beliefs, stories, and images.

Archaic

2500-200 BCE

The earliest people lived at seasonal campsites in rock shelters. These

small mobile groups made hunting and gathering expeditions, covering

familiar territory on the canyon floor and upland plateau. Extremely

steep trails, marked by images painted on canyon walls and boulders,

connected the ranges.

Canyon de Chelly provided abundant food for these first settlers. They ate deer, antelope, rabbit, and other animals, and over 40 varieties of plants. Through foraging trips these people gained an understanding of the canyon and its sources of year-round water. This knowledge would eventually be used to cultivate a new plant introduced from the south—corn.

Basketmaker

200 BCE-CE 750

About 2,500 years ago a fundamental change occurred in how people lived

here. Instead of relying on hunting and gathering, a group called

Basketmaker—named because of their extraordinary weaving

skills—learned how to farm. They tucked small fields into corners

of the canyon or carved them on the mesas. Over time farming techniques

improved, leading to a consistent supply of corn, squash, and beans.

With agriculture these people became more sedentary. They built

communities of dispersed households, large granaries, and public

structures.

Basketmaker rock paintings show a society of extended families growing and storing food and engaging in religious and communal activities.

Pueblo

750-1300

About 1,250 years ago the dispersed hamlets gave way to a new kind of

settlement—the village. Why this change occurred is unclear.

Perhaps rock shelter households became too crowded. Perhaps conflict

forced people to band together for defense. Maybe they simply wanted to

live closer to their farms. These people raised turkeys for food and

grew cotton, a crop that led to new weaving techniques.

Villages offered opportunities for social interaction, trade, and ceremony. These Puebloan people crafted beautiful pottery, and created a landscape that was useful and spiritual.

Hopi

1300-1600

Puebloan life ended here about 700 years ago. Drought, disease,

conflict, and possibly the allure of ideas from the south led the people

to leave the canyon. They moved south and west, establishing villages

along the Little Colorado River and at the southern tip of Black Mesa.

In time, these people became the Hopi.

The Hopi describe these events as part of a migratory cycle. Traditional histories and archeological evidence chronicle seasonal farming, pilgrimages, and occasional stays in the canyons. This pattern continued until the Navajo arrived in the 1700s.

Navajo

1700-1863

The Navajo, an Athabaskan-speaking people, entered Canyon de Chelly

about 400 years ago. They brought domesticated sheep and goats and a

culture tempered by centuries of migration and adaptation. Like those

before them, the Navajo used the canyons and the plateau to support a

way of life.

Canyon de Chelly was known throughout the region for its fine corn fields and peach orchards planted on the canyon floor. Small settlements set in clearings gave the landscape a tranquil quality.

Tranquility ended in the late 1700s as warfare erupted among the Navajo, other tribes, and Spanish colonists. Quick raids and certain reprisal characterized these conflicts over animals and land.

The Navajo took refuge in Canyon de Chelly's serpentine canyons. They fortified trails with stone walls, sheltered in rock alcoves, and stockpiled food and water. Despite such precautions, Spanish, Ute, and US military parties breeched the defenses, leaving death in their wake. Navajo traditional stories give testimony of these times. Archeological remnants of the canyon's fortified places and rock paintings graphically narrate the Navajo's endurance.

The Long Walk

1863-1868

In 1846 the US army, under Stephen Watts Kearny, subdued Mexican forces,

claiming present-day Arizona and New Mexico as US territory. Kearny

proposed a peace agreement to end decades of mutual raiding among

tribes. But for the next 17 years the conflict continued, and so did

military expeditions into Navajo territory.

In 1863 Col. Kit Carson began a brutal campaign against the Navajo. In the winter of 1864 Carson's troops entered the eastern end of Canyon de Chelly and pushed the Navajo toward the canyon mouth. Resistance proved futile; most Navajo were captured or killed. Carson's forces returned in the spring to complete their devastating campaign. They destroyed the remaining hogans and orchards, and killed the sheep.

A bitter, humiliating trial awaited those Navajo who survived the ordeal. Forced to march over 300 miles, called the Long Walk, to Fort Sumner in New Mexico territory, scores perished from thirst, hunger, and fatigue. Their years of internment at Fort Sumner were no kinder. Poor food, inadequate shelter, and disease brutalized the survivors. In 1868 the US government finally allowed the Navajo to return home to rebuild their lives.

Trading Days

1868-1925

The Navajo returned home to find their hogans, crops, and sheep gone.

Again they faced starvation. Food distribution centers, like the one at

Fort Defiance in Arizona territory, helped the Navajo recover. These

centers and practices taken from Spanish and Mexican traders provided a

model for the trading posts that grew up in Navajo country.

Trading posts became focal points for Navajo communities—places where people could exchange news, discuss problems, and trade their jewelry, rugs, and crafts for staples. Traders set up posts near Canyon de Chelly and in surrounding areas, including Hubbell Trading Post at Ganado. Sam Day's 1902 trading post is now part of the concessioner's restaurant.

Navajo of the Canyon Today

White House is not a Navajo structure. Built and occupied centuries ago by ancestral Puebloan people, it is named for a long wall in the upper dwelling that is covered with white plaster.

Within an enclosure formed by four sacred mountains, a canyon cradles the history and the culture of Diné—the Navajo people. To the outside world it is known as Canyon de Chelly. To the people who live here it is Tsegi (SAY-ih), a physical and spiritual home.

The smell of wood smoke and the distant sounds of sheep bells, barking dogs, and children playing tell us that Diné still live here. Alfalfa, corn fields, and small orchards surround the traditional log hogans on the canyon floor, weaving a tapestry of everyday life.

To Diné the canyon means more than a summer home or a place to raise sheep and corn. The Diné culture emerged from this land. Our language refers to the landscape, and the people identify themselves by this.

Diné are connected with the landscape of Tsegi, deriving meaning, culture, and spirituality from the natural features that surround them. The land nourishes our people, and it is intrinsic to the activities of daily life.

Our elders are especially close to the land. From their stewardship comes a set of ethics based on experience and tradition. With their teachings, stories, and songs, our traditions are sustained through the generations.

Cycles of the Sun, Earth, and moon, and seasons, ceremonies, and generations are part of the continuity of life in Canyon de Chelly. Respecting Mother Earth is key to harmonious life.

Each person's well-being contributes to the health of the family and community. This perspective helped the Navajo people recover from the trauma of the Long Walk.

Canyon de Chelly, then and now, is the epicenter of Navajo culture. People who live here retain that spirit of their ancestors. Traditional beliefs are reflected in everyday life—in how Navajo care for their families, livestock, and homes, and how plants are collected for ceremonial, medicinal, and traditional uses.

Yet, DiDinéne thrive on new experiences. For our health, we maintain traditions to help preserve our way of life, while we adapt to changes in the physical world. Adhering to this belief makes Diné a truly bicultural society. As a Navajo Nation leader once said, "We will be like a rock a river has to go around."

Ailema Benally, Navajo

Plants of Canyon de Chelly—Tséyi 'dęęnanise' altaas'éí

Tradition says that Haashch'eeh diné e, the Holy People, created plants from the air, water, light, and soil to beautify the land and to provide for Diné, the Navajo people. The Navajo respect plants as a perpetually renewing gift and as being connected with all things on Earth.

For centuries Diné have raised crops and collected plants for food, medicines, dyes, and ceremonies. Traditional plant use continues today. Farmers plant corn in the canyon as their ancestors did before them. Hataalli, chanters (medicine men and women), collect wild plants to use for medicines and ceremonies. Here are a few of the plants you may see at Canyon de Chelly, along with some of their uses.

Narrowleaf yucca Long, stiff leaves with sharp ends grow from a central clump. A single stalk of white flowers reaches four feet. Ceremonial, soap from root cleanses hair; fibers used for weaving baskets. Other: dyes; edible fruit.

Sumac This shrub, also called lemonade berry plant, produces tart, sticky berries. Food: berries, sugar, and water make a beverage; dried berries mixed with cornmeal make a pudding. Other: dyes; fibers used in hoops and to weave water jugs and ceremonial baskets (left).

Prickly pear cactus This sprawling cactus with flat, waxy pads (leaves) grows throughout the canyon area. Flowers emerge along top edges of pads, forming plump red fruit. Medicinal: peeled pads reduce bleeding. Food: edible fruit and pads. Other: fruits make bright red and pink dyes; stems make glue.

Snakeweed This short shrub has a dense halo of yellow flowers that bloom from July through September. Medicinal: heals cuts and bites. Ceremonial, used to make purifying incense.

Sagebrush Silvery-green leaves and a strong aroma distinguish this shrub. Medicinal: roots, leaves, and tassels used in healing remedies; tea relieves stomach problems Food; flavoring. Other: gold and yellow-green dyes.

Juniper This evergreen tree grows to 25 feet. The blue, fleshy berries are its cones. Medicinal: relieves headache and flu symptoms. Ceremontal: cleanses and purifies. Food; adds flavor and potassium and other minerals. Other: dried berries used to make necklaces.

Planning Your Visit

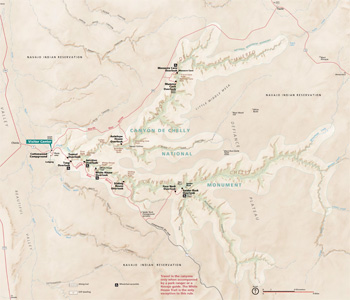

(click for larger maps) |

Take time to enjoy this place of magnificent beauty. You may tour the Rim Drives or hike the White House Trail on your own. You can also experience the canyon by taking a tour with an authorized Navajo guide.

Visitor Center

Start here for information, exhibits, and a bookstore. The visitor

center is open every day except December 25. No entrance fee.

Guided Tours

Private vendors offer hiking, backcountry camping, horseback, and

4-wheel-drive vehicle tours into the canyon with an authorized guide.

Prices vary according to the type, length, and difficulty of the trip.

For information ask at the visitor center. Permits are required; only

vendors registered with the Navajo Nation and National Park Service may

lead canyon tours.

White House Trail

This 2.5-mile round-trip trail is the only place where you may enter the

canyon without a permit or an authorized Navajo guide. Allow two hours

for the round-trip hike. You descend 500 feet to the canyon floor, cross

Chinle Wash, and view the cliff dwellings. Chinle Wash may contain water

during the spring snowmelt or rainy periods. Vault toilets are available

at the bottom. There is no drinking water—you must carry plenty of

fresh water. Expect extreme temperatures. Stay on the trail. Please

respect the fragile environment and the privacy of Navajo people. Do not

enter dwellings or disturb historical or natural features, which are

protected by federal and tribal laws.

Camping

Navajo Parks and Recreation Department manages Cottonwood Campground.

Open year-round. Group sites require reservations. Grills, tables, and

restrooms available. No showers or hookups. The maximum RV length is 40

feet.

Accommodations

Chinle offers lodging, food, gas, and supplies. The park concession

operates a restaurant, gift shop, and motel in the park.

North Rim Drive—

34 miles round-trip

Some beautiful cliff dwellings are along this drive. Besides the

well-known dwellings, watch for small sites that dot the alcoves and

blend in with the canyon walls.

• Antelope House Ruin is named for the illustrations of antelope attributed to Navajo artist Dibe Yazhi (Little Sheep) who lived here in the early 1800s. Excavated in the 1970s, this site has an unusual circular plaza built in the 1300s.

• Navajo Fortress is a historic landmark used as a refuge by early Navajos.

• Mummy Cave Ruin is one of the largest ancestral Puebloan villages in the canyon and was occupied to about 1300. The east and west alcoves comprise living and ceremonial rooms. In the 1280s people who migrated from Mesa Verde built the tower complex that rests on the central ledge.

• Massacre Cave refers to the Navajo killed here in the winter of 1805 by a Spanish military expedition led by Antonio Narbona. About 115 Navajo took shelter on the ledge above the canyon floor. Narbona's men discovered them, then fired from the rim, killing all the people on the ledge.

South Rim Drive—

37 miles round-trip

This drive offers panoramic views of the canyons, Defiance Plateau, and

the Chuska Mountains to the northeast. Watch for changes in vegetation

and geology as the elevation rises on the drive to Spider Rock.

• Tsegi Overlook provides views of Navajo farmlands on the canyon floor.

• Junction Overlook has views of Chinle Valley and the confluence of Canyon del Muerto and Canyon de Chelly.

• White House Ruin Ancestral Puebloans built and occupied this place about 1,000 years ago. It is named for the long, white plaster wall in the upper dwelling. The 2.5-mile round-trip White House Trail begins from this overlook.

• Spider Rock is an 800-foot sandstone spire that rises from the canyon floor at the junction of Canyon de Chelly and Monument Canyon. From here you can see the volcanic core of Black Rock Butte and the Chuska Mountains on the horizon.

For Your Safety

Please be aware of these conditions and regulations:

• The canyons

are deep, with steep, vertical walls. Falls can be fatal. Use extreme

caution at canyon rims. Stay on trails and behind protective walls. Keep

control of children and pets at all times. • Watch out for snakes,

stinging insects, and thorns. Do not put your hands or feet into dark

places. • Keep pets leashed at all times. They are not allowed on the

White House Trail or in the canyon. • Always lock your vehicle. Secure

valuables out of sight or take them with you. • Alcohol is prohibited in

the park and anywhere on the Navajo Reservation. • Do not harm, feed, or

harass wildlife. • Federal and tribal laws protect all natural and

cultural features in the park. Entering archeological sites or

collecting artifacts is strictly prohibited. • Do not pick or disturb

plants; many are used by Navajo people and grow in traditional plant

collecting areas. • For firearms regulations check the park website.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website.

Emergencies call 911

Visiting Navajo Land

The Navajo Reservation observes daylight saving time, but the rest of

Arizona and the Hopi Reservation do not. Clocks on the Navajo

Reservation then read one hour ahead of clocks off the reservation, like

those at the Grand Canyon.

The Navajo Tribe has its own police department. Drive carefully and obey speed limits. This is open range land; watch for livestock on roads. Ask permission before photographing or drawing people or their homes; a fee is usually expected. Be aware that this is private land. Do not hike or drive off roads without permission. Please respect Navajo Nation property rights.

Source: NPS Brochure (2013)

Documents

A Catalog of Upper Triassic Plant Megafossils of the Western United States Through 1988 (Sidney Ash, 1989)

A Socioeconomic Atlas for Canyon de Chelly National Monument and its Region (Jean E. McKendry, Cynthia A. Brewer and Joel M. Staub, 2004)

Administrative History: Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona (HTML edition) (David M. Brugge and Raymond Wilson, January 1976)

An Archeological Assessment of Canyon de Chelly National Monument Western Archeological Center Publications in Anthropology No. 5 (James A. McDonald, 1976)

Archeological Investigations at Thunderbird Lodge, Canyon De Chelly, Arizona Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 20 (Peter J. McKenna and Scott E. Travis, 1989)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Canyon de Chelly: The Story of its Ruins and People (Zorro A. Bradley, 1973)

Canyon de Chelly: The Story of its Ruins and People (Zorro A. Bradley, 1976)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Establishing Canyon de Chelly National Monument: A Study in Navajo and Government Relations (Raymond Wilson, extract from New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 51 No. 2, 1976, ©University of New Mexico)

Excavations at Tse-Ta'a, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona Archeological Research Series No. 9 (Charlie R. Steen, 1966)

Floodplain Analysis for the Garcia Trading Post Area, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Chinle, Arizona NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-90/05 (Gary W. Rosenlieb and Gary M. Smillie, October 1990)

Foundation Document, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona (December 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona (February 2016)

Geologic Map of Canyon de Chelly National Monument (May 2024)

Geologic Report, Canyon de Chelly National Monument Southwestern Monuments Special Report No. 20 (Vincent W. Vandiver, July 1937)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Canyon de Chelly National Monument NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/159 (Katie KelleryLynn, July 2024)

Historic Structures Report: Chinle Trading Post, Thunderbird Ranch and Custodian's Residence, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Arizona Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Paper No. 17 (Laura S. Harrison and Beverly Spears, 1988)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Worksheet, Canyon de Chelly National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Canyon de Chelly National Monument (Charles B. Voll, August 11, 1970)

Non-Destructive Archeology at Sliding Rock Ruin: An Experiment in the Methodology of the Conservation Ethic (Larry V. Nordby, December 1981)

Park Newspaper (Canyon Overlook): 1984 • 1986 • 1987 • 2000-2001 • c2020s

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Resource Management, Science and Stewardship News, Canyon de Chelly National Monument (Issue No. 1, Spring 2005)

The Navajo country--a geographic and hydrographic reconnaissance of parts of Arizona, New Mexico and Utah USGS Water Supply Paper 380 (Herbert E. Gregory, 1916)

The Cliff Ruins of Canyon de Chelly, Arizona Bureau of American Ethnology, 16th Annual Report (Cosmos Mindeleff, 1897)

Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Report, Canyon de Chelly National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SCPN/NRTR-2010/306 (Kathryn A. Thomas, Monica L. McTeague, Lindsay Ogden, Keith Schulz, Tammy Fancher, Robert Waltermire and Anne Cully, April 2010)

cach/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025