|

CCC Forestry

|

|

Chapter XIII

FOREST RECREATION

|

FREQUENT reference has heretofore been made to the recreational values of forests. The growth of forest recreation since 1916 has in some sections placed it at the top of the list as a forest value. In 1916, 237,357 persons visited the national parks, and in 1931, 2,999,451. Records of visitors in the national forests in 1917 showed a total of 3,132,000, whereas the 1931 reports showed a total of 32,288,613. In 1935 the forest service recorded 41,725,000 visitors. The following tabulation from "A National Plan for American Forestry"1 shows the popularity of these natural playgrounds and resting places during the year 1931: Class of forest land

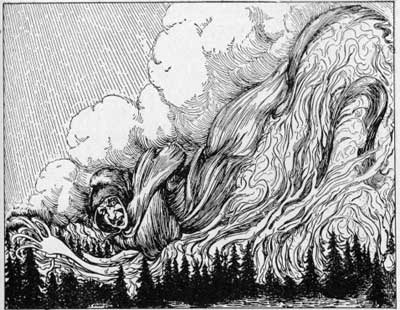

These figures, of course, contain many duplications. Many people visited two or more areas and some spent only an hour in the forests. Others, however, spent weeks or even the entire summer in camps and summer homes. It is safe to assume that an average of 1 day each was spent in the forests by the 246,900,000 persons who visited them in 1931. Increased population and increased leisure time undoubtedly have been important factors in raising the popularity of forest recreation. Probably the most significant factor has been the almost universal use of the automobile as a means of transportation. Coupled with these factors has been the activity of the CCC in recent years, in making the forest more accessible to the motorist and the hiker, in improving recreation and scenic values, as well as in increasing the utility of the forest as a producer of wood. Numerous attempts have been made to evaluate forest recreation in terms of dollars and cents. Probably the most easily understood figures are those of Robert Marshall: Assuming that a day spent in the forest has a recreational value equal to that of a 25-cent motion-picture show (and many recreationists deem this comparison unfair to the forest), the man-days spent in forest recreation (approximately 250 million) have a value of 62-1/2 million dollars. In spite of the conservative value placed on a day in the woods by this authority, the final figure is high.

The value of forest recreation to industry has been placed at $1,750,000,000—1 billion dollars for motor travel, one-half billion for hunting and fishing equipment, and one-quarter billion for summer homes, resorts, and hiking equipment. |

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Seven types of areas have been recognized in "A National Plan for American Forestry" to fill the requirements of as many classes of recreationists. Superlative areas: Unique and outstanding scenic, scientific, or historical values characterize certain localities. Grand Canyon, Crater Lake, the volcanic regions of Yellowstone National Park, and the big tree and redwood forests of California are "superlative areas." Most of such areas have been set aside for recreational use and study in national parks, national monuments, national forests, and State parks, although a number of them are privately owned. The size of a superlative area depends upon the superlative characteristic itself and upon the number of people that visit it. Primeval areas: From a scientific standpoint, the preservation of "primeval areas" or "natural areas" is of major importance in studying the laws of nature as applied to forest growth. These areas of virgin timber have also a great recreational value particularly to people who wish to escape from the artificialities of modern life to the quietude of the forest primeval. To satisfy both scientific study and recreational relaxation such areas should be at least 5,000 acres in extent. Smaller areas of about 1,000 acres may be adequate for research and study. Wilderness areas: Tracts of forest land, with no permanent inhabitants, no roads for automobile traffic, and large enough to enable a person to spend a week or more of travel in them without back-tracking, are designated as "wilderness areas." Such areas should be at least 200,000 acres in extent, and should be free from the marks of civilization, except where improvements such as telephone lines and towers are necessary for fire protection. Wilderness conditions may still be found in extensive areas of the West and in a few sections of the East. The problem of establishing wilderness areas is not one of development, but of retarding or restraining the encroachment of civilization. Roadside areas: Strips of timbered land left uncut along highways and important roads are known as "roadside areas." Ranging from 125 to 250 feet in width, these strips help beautify automobile travel. Similar strips left along the shores of waterways and lakes add to the pleasure of boat travel. Camp-site areas: Camping is one of the major activities of forest recreationists. This activity has been recognized in the setting aside and development of areas for campers. Their location is governed largely by accessibility and water supply, and they may range in size from one quarter acre to an area large enough to accommodate more than a thousand camps. Residence areas: In 1931, 493,235 summer home sites were rented on the national forests and many State and private land holders also supplied sites for summer homes, hotels, stores, sanitaria, and other special uses. The tracts of land for these activities vary greatly; probably one-quarter acre is the minimum size. Outing areas: The recreationist who desires a spot away from the noise and dust of the highway, which although used for timber production and equipped with administrative roads and trails, has not been injured scenically, finds "outing areas" suited to his need. These areas may be only 4 or 5 acres or many thousands of acres in extent. Outing areas adjacent to superlative or primeval areas provide camping facilities without marring natural beauty.

|

The forest provides quiet atmosphere for summer cottages.

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

CAMPGROUND IMPROVEMENTS To obtain the maximum use of forest recreational areas and to protect them against destructive use, it is necessary to establish improvements. With the exception of camp-site areas very little is needed to provide adequate recreational opportunities. At camp sites, however, people are likely to congregate in great numbers, and planning and development are necessary. In developing a recreational area, the natural beauty of the spot must not be lost through the building of facilities which do not blend well with the landscape. Each camp site presents a problem that is best solved on the site itself. There are, however, fundamental developments which are part of any well-planned camping area.

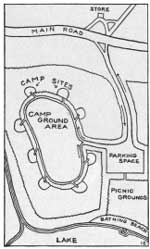

Camp-site improvements vary widely throughout the country. Each region, each State, in fact each recreational area has its own peculiarities of design. The great diversity of campground planning is accounted for by the fact that this is a new phase of forest administration. Definite plans have been developed by some Forest Service regions and by a few of the States. They are becoming coordinated as time and public use prove their worth. LOCATION OF CAMP SITES The most important factor in the location of a camp site, for the average tourist or week-end visitor, is its accessibility. Camp sites are developed to supply a recreational demand—the demand of the camper who does not wish for too great exertion. Campers of the rugged woodsman type usually spurn the refinements of prepared camp sites, and choose isolated spots far from traveled roads. For the city dweller who takes his family on a week-end camping trip, the campground planner must combine scenic values with easy access and must temper the ruggedness of the outdoors with facilities for comfort and rest. To be accessible a camp does not have to be situated on the shoulder of a main highway or on the outskirts of a large town. It should be so located, however, that campers may approach within easy walking distance by automobile. One-way, loop roads from the main highway to the camp area will provide this access and will tend to limit the travel of noncampers through the area. The campground should be on level ground—steep slopes are undesirable. Although scenic beauty is pleasing and should be a part of every camp-site area, it is not as important to the camping area as pure water supply, good drainage, and comfort. Swampy ground, rockslides, old stream beds, low flats which may be flooded in high water, and extremely windy areas should be avoided. CLEARING Campers are attracted to the forest by the trees and other natural vegetation. Unnecessary removal of trees and shrubs, therefore, defeats the purpose of the campsite. Only such vegetation should be removed as interferes with the safety and comfort of the campers. Brush and undergrowth and fallen trees which constitute fire hazard should be cleared away, and dead or dying trees which are likely to fall across the camp site should be cut down. Sufficient clearing and cleaning must be done to accommodate tents, shelters, and other facilities, but this clearing must not be overdone. When in doubt as to whether a tree or clump of brush should be cut, it is wise to let it remain.

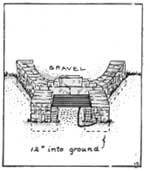

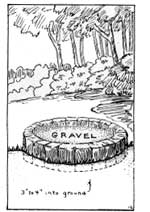

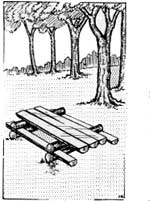

SIGNS AND POSTS Like billboards on public highways, campground and trail signs may be unnecessary eyesores if they do not blend in with their surroundings. Picturesque, rustic signs, if they are not too numerous or conspicuous, tend to make the public conscious of the forest and instill a desire to keep the campground clean. Signs should be simple in their construction and design, and should be built of native material of durable character. Native shrubs form a good background. CAMP STOVES AND FIREPLACES When visitors are permitted to build fires at will in a campsite area, the spot soon becomes a mess of ash heaps. These ash heaps, besides being unsightly, have a poisonous effect on plant growth. Rain beating down on them washes lye into the soil so that in a relatively short time all nearby vegetation is seriously damaged or killed. Permanent stone or brick fireplaces offer better cooking facilities than do open fires, and campers will take advantage of them if they are conveniently placed. Besides reducing the number of ash heaps, stone fireplaces reduce fire hazard. Native stone is used for fireplace construction, but often it must be lined with firebrick to prevent it from cracking and crumbling. The simpler fireplaces are short parallel walls of stones but the more elaborate ones have chimneys and are equipped with cast-iron grates or steel plates to hold utensils for cooking. A ring of native stone filled with gravel to form an elevated hearth can be used for campfires or bonfires. Such an arrangement will attract the campers and will tend to limit the size of the fire. TABLES AND BENCHES Two-inch planks may be used for table tops and bench tops and 4 by 6 material may be used for legs. Furniture of lighter material will not stand the rough camp usage, and is too easily moved from place to place. Attractive tables and benches may be constructed of 12-inch peeled logs with their top surfaces hewed flat. These are spiked together to form table and bench combinations as shown in the sketch. Rustic picnic tables may be built of peeled, stained, native cedar logs about 4 inches in diameter with 2-inch planks for seats and table tops.

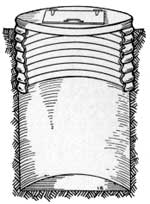

GARBAGE PITS The indiscriminate disposal of garbage at popular camp sites results in a messy area uninviting except to scavengers and flies. Campers will use garbage pits if the pits are well placed, and if they are inspected frequently. When the pits are filled to within about eight inches of the top, new ones should be dug, and the old ones should be covered with rocks and earth. If garbage is permitted to pile up near the ground surface, animals may uncover old pits. Pits are dug not less than 4 feet in depth, and the sides are lined with rock or supported by corrugated pipe. Standard tops, with hinged lids, either of galvanized iron or wood may be removed from old pits and placed on new ones. INCINERATORS For burning trash, stone incinerators may be built of native material topped with a screen lid to prevent the escape of large sparks and burning material. Draft openings are made at the ground level on opposite sides of the incinerator. WATER SUPPLY Campsite areas must have a supply of fresh, pure water, and springs must be improved to meet this demand. Although one or two campers may use a natural unimproved spring without spoiling it, a number of visitors over a long period of time can make a muddy swamp of a small free-flowing spring. Protecting boxes for springs may be of many types, but concrete or stone have proved most satisfactory and permanent. Before a spring box is built, the spring must be cleaned out and all impediments to flow must be removed. The box is then built to enclose the spring completely. Suitable, tight-fitting covers are necessary to keep out leaves, earth, and insects, and to prevent pollution by animals. Springs from a height outside the camping area may be piped to a faucet in camp. Adequate drainage for overflow must be provided. Paving with gravel or stone will prevent the area around the spring or faucet from becoming muddy. The development of springs and water lines is explained in the Forest Service publication Manual for Small Water Developments.2 The services of an engineer and campground planner are usually necessary in laying out pumps, hydrants, pipes, and other water facilities. Water requirements are computed according to the number of people using the area and the type of water using facilities installed. For camps not provided with flush toilets, about 5 gallons per person per day fills all demands; but for the more elaborate camps, equipped with cabins, flush toilets, baths, and lavatories, from 25 to 50 gallons of water per person per day may be necessary.

LATRINES The location of latrines, with reference to other camp-site facilities, is very important. They should be no closer than 100 feet from streams and water supply, and should be no farther away than 300 feet from the camp spot. The number of latrines will be determined by the number of people who use the camp-site area. One unit may be expected to serve for three camp spots (about 15 people). Of the three common types (pit, chemical, and flush) the pit latrine is the cheapest. In small camps this type is adequate, but it is more difficult to keep sanitary than are the more elaborate types. Flush latrines should be installed in camp areas serving a large number of people and where adequate water supply and good drainage can be provided without contaminating springs and drinking water. In porous soil where the drainage is not near the water supply cesspools may be used, but septic tanks are far better. Chemical latrines are safe near water supplies as they sterilize and liquefy the sewage. These, however, demand constant care and supervision. MISCELLANEOUS IMPROVEMENTS A camp site may have a number of other facilities, depending upon its use. Near streams and lakes, boat landings, diving boards, beaches, wading pools for children, and bath houses are provided. Some of the larger camps are equipped with laundries, shower baths, playgrounds, pavilions, and recreation halls. As recreational use continues to grow, more and varied facilities will be demanded. |

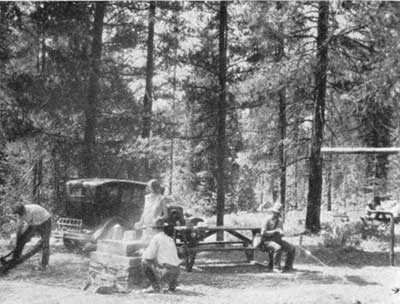

Combining Comfort, Accessibility, and Outdoor Ruggedness.

Pure Water Supply and Good Drainage Are Necessary.

Too Many Users Can Spoil a Spring.

The Number of Visitors Determines the Extent of Water Facilities.

| |||||||||||||||||||

|

Although forest recreation is still in its infancy as a phase of forest administration, it is growing rapidly. Its growth has been due to a number of developments in modern civilization—increased population, shorter working hours, raised standards of living, ease of transportation, and increased nervous strain and pressure of business life. These developments are increasing in influence and a corresponding increase in demand for recreational areas may be expected. No plan for development of recreational areas should be too limited or too rigid to allow for future expansion. Structural improvements vary in the regions and States; new ideas and new facilities characterize the development of each new area. The interchange of plans between the agencies responsible for recreational development will bring about the greatest recreational use of each area. In planning recreational developments it is important to preserve natural conditions and natural beauty. Other forest uses may be coordinated with recreation. Clear cutting usually leaves an area unattractive to vacationists. Where forest land is demanded for recreational use, a system of selection cutting will provide for timber harvest and will not seriously harm its hiking, hunting, fishing, and outing possibilities. Many forest areas have been separated into units of use—units where recreation is of major importance, units where it is of equal standing with timber harvest, and units where timber harvest is of major importance. In the first units, no cutting is done if it will interfere with recreational use; in the second, both uses are coordinated; and in the third, recreational use is not permitted to interfere with timber culture or harvest. Flexibility in the designation of these units is necessary to meet the requirements of changing forest uses.

Forests offer inexpensive recreational opportunities which appeal to rich and poor alike. Low priced automobiles and good roads have made the forest accessible to thousands of American workers. It is possible, however, to extend forest recreation to many more city dwellers by establishing picnic and outing areas near cities and towns or by providing transportation at reduced rates for those who otherwise would not have an opportunity to spend an occasional "day in the woods." |

Natural Conditions, Recreation, and Utility Are Coordinated. Units of Use— Recreation, Timber Recreation, Timber Culture.

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

ccc-forestry/chap13.htm Last Updated: 02-Apr-2009 |